Chance Encounters, Edition 13

Van Gogh and the Avant-garde: The Modern Landscape at the Art Institute of Chicago

In the 1880s a group of young French painters turned their attention to Parisian suburbs northwest of the city along the Seine River. Focusing on landscape paintings created by these artists, The Art Institute of Chicago’s current exhibition, “Van Gogh and the Avant-garde: The Modern Landscape” (open through September 4), reveals the inspiration these artists found in the river and its environs between 1882 and 1890. The exhibition’s emphasis is on Vincent van Gogh, but his 25 works are interspersed with related works by his colleagues and friends, Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, Émile Bernard, and Charles Angrand. The five artists worked solo and in different pairings in the towns of Asnières, Clichy, and Courbevoie. For the artists living in Paris, these northwestern suburbs were accessible by train and on foot and each provided the artists with a different quality: rural, industrial, recreational.

In this edition, I will share some of the paintings from this charming exhibition which I visited last week. Organized by geography and theme, the galleries exhibiting the works of art are encircled by a hallway which displays a timeline highlighting the travels, meetings, and interactions of the artists. The first artist to discover this region of the Seine was Georges Seurat who began working there in 1881, completing his major work set there, Bathers at Asnières, in 1883. Through their friendships and professional contacts, other artists were soon joining him to draw and paint there. Van Gogh was a latecomer, not working in the area until 1887. The region was popular with tourists as well as artists and many amenities for visitors were available. Van Gogh’s Restaurant Rispal at Asnières (above) captures one of the fashionable dining spots in the town. This is a rare vertical composition for the artist and was Van Gogh’s largest work made at Asnières. The artist captures the blue skies, flowering trees, and sunlit streets with a brighter palette than he had used before his arrival in Paris in 1886. The sky looks almost Impressionist in its use of blended color but the lower half of the painting shows the textured large brushstrokes influenced by Van Gogh’s interaction with pointillist artists.

A partial inspiration for Van Gogh’s visible brushwork was his contact with the Neo-Impressionist artists Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, and Charles Angrand. The Seine at Coubevoie by Seurat shows that artist’s approach to pointillism, the characteristic technique of Neo-Impressionism. Seurat laid down areas of solid color and then built up small spots of complementary (opposite) or analogous (related) color to create light and shadow and to represent texture. Notice the tiny brushstrokes in the foreground, the longer vertical marks in the tree trunk, and the long brightly colored horizontal strokes in the water. In person, the bright water seems to flicker as if the water is moving. The subject of this work is reminiscent of Seurat’s masterpiece, displayed elsewhere in the Art Institute, Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884-1886. When Seurat created The Seine at Courbevoie, work on preparatory studies for La Grande Jatte was already underway and the elegantly dressed woman, the running dog, and the sailboat reflect the leisure activities along the river which were also the subject of Seurat’s most famous painting.

Seurat’s colleague in founding the Neo-Impressionist movement was Paul Signac and his painting Clipper depicts the popular Seine pastime of sailing. Leisure time on the river is contrasted with the railroad bridge to the right and the industrial structures barely visible behind the waterfront buildings. At the left edge of the composition, can be seen a bit of the pedestrian bridge that also crossed the Seine at Asnières. The two bridges appear frequently in the exhibition, representing its stated theme of “The Modern Landscape.” The entire painting is created from a palette of red-orange, blue and yellow with only a small amount of green in the foliage of the far river bank. This use of color demonstrates the Neo-Impressionist belief in creating harmony through color. The bridge supports clearly show the use of complementary colors for shadows (blue and orange) and analogous colors (orange and yellow) for highlights.

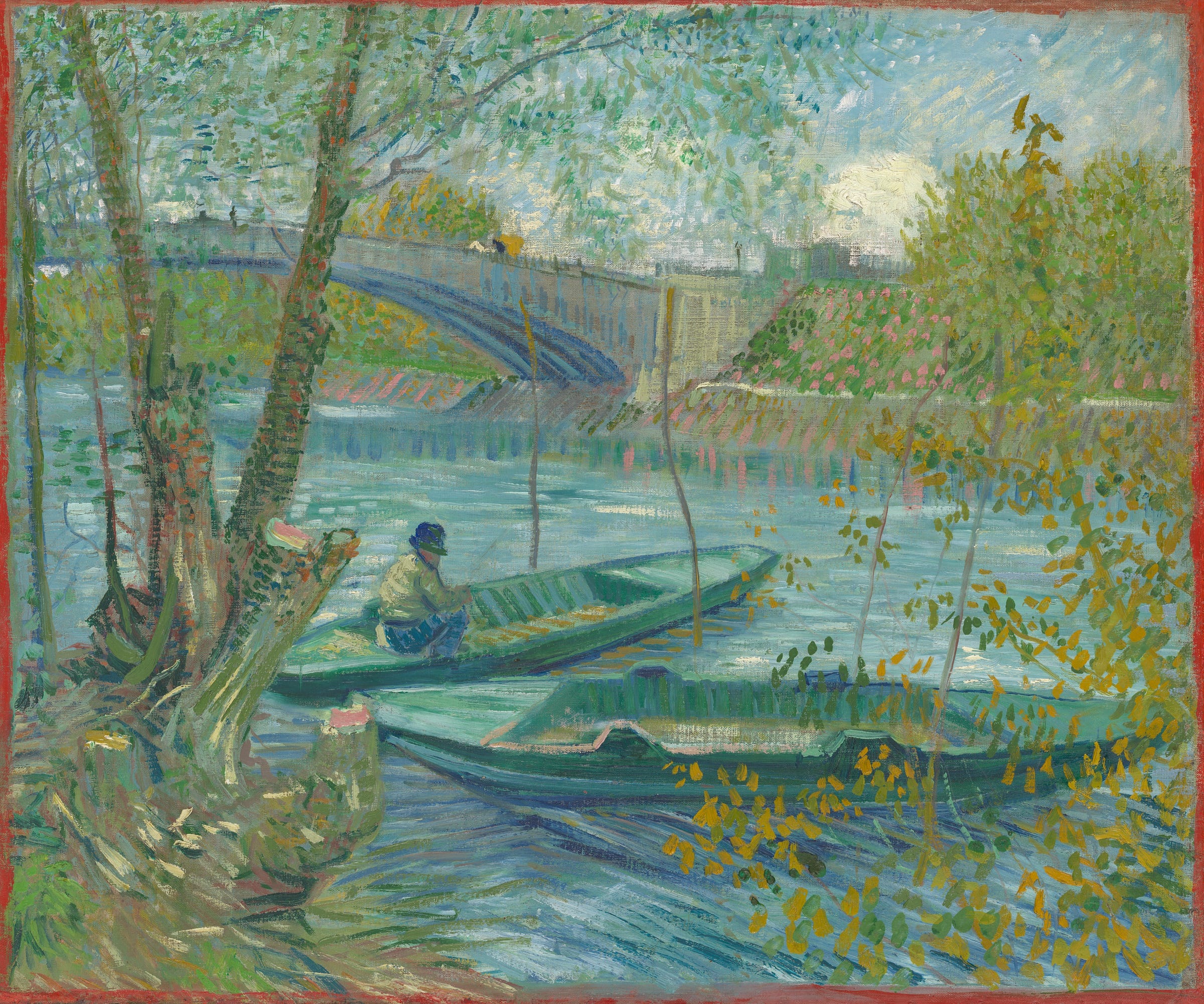

Leisure on the Seine is the subject of Vincent van Gogh’s Fishing in Spring. What struck me when looking at this painting in person was the artist’s prominent use of pink as a foil for the dominant green and blue-green color palette. In addition to dots of pink among the foliage, the centers of cut tree trunks and the slope of the far shore are created from noticeable pink marks. Van Gogh’s less formulaic use of brushstrokes contrasts with the Neo-Impressionist’s approach. Already Van Gogh is starting to use his application of paint expressively, though not as thickly as in later works like The Starry Night (1889, Museum of Modern Art, New York). The bright orange border painted around this composition is found on two other works by Van Gogh in this exhibition, A Woman Walking in a Garden (1887, private collection) and River Bank in Springtime (1887, Dallas Museum of Art, Texas). This is one of three triptychs (three panel groupings) that scholars have identified among Van Gogh’s works from this phase of the artist’s career and the only one shown in full in the exhibition. The concept of the triptych recurred later in the artist’s life when he planned a triptych consisting of La Berceuse (The Lullaby) flanked by paintings of sunflowers.

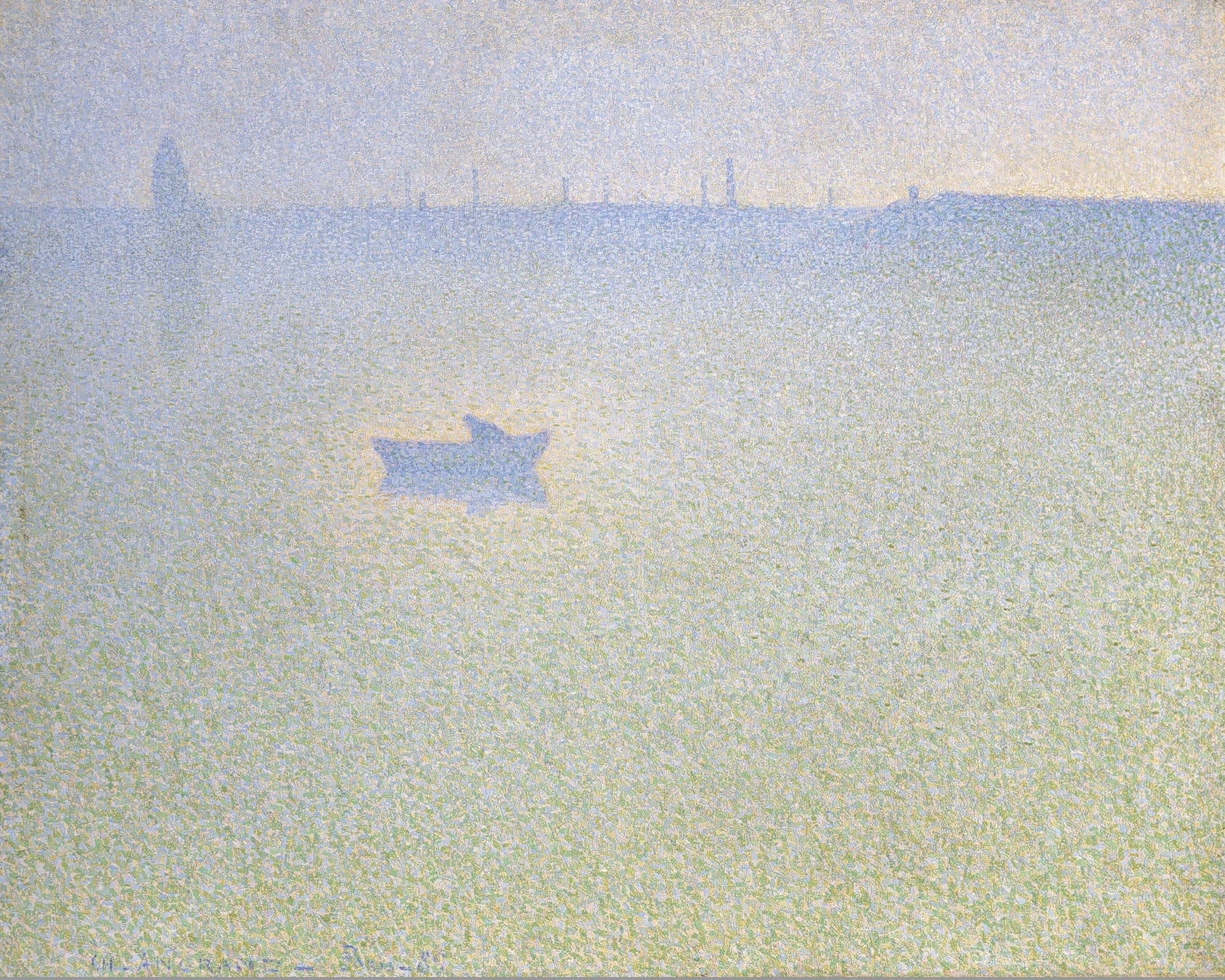

Another of the recurring themes in this exhibition is the pleasures to be found in nature. Charles Angrand’s The Seine at Dawn, which shows a fisherman on the river at sunrise, was my favorite painting in the show. The pale colors and pointillist technique create an almost uncanny shimmer and glow. The shimmer is achieved by the tiny irregular flecks of pale color that Angrand applied atop a base layer of color. The glow appears to come from the lighter color surrounding the boat and fisherman, and the suggested light of the rising sun above the horizon on the right. I wish a reproduction matched the beauty of this work when seen in person. At a later point in his life, Angrand referred to this painting as a “symphony in gray,” though gray is not the color I’d have used to describe this sparkling picture. Angrand’s description does suggest that the artist was familiar with the American painter J.A.M. Whistler’s practice of naming his compositions with musical terms like nocturne, harmony, and symphony.

A work that stands out stylistically in this exhibition is Émile Bernard’s Iron Bridges at Asnières. Though the bridges over the river interested all of the artists in the show, Bernard’s boldly colored, outlined forms are more dramatic than any of his colleagues’ works. Bernard experimented with, but ultimately rejected pointillism and this is the first work in which he used his new style, Cloisonnism, in which well-defined lines enclose areas of saturated color. The appearance is reminiscent of the raised metal outlines surrounding bright enamel in cloisonné metalwork. The bold shapes and bright colors contrast sharply with the precise technique of the Neo-Impressionists and with the busy brushwork of Van Gogh. Nevertheless, Bernard was one of Vincent van Gogh’s closest artist friends; they worked together frequently when both lived in Paris and maintained a lively correspondence after Van Gogh left Paris.

The Bridge at Courbevoie by Van Gogh features another bridge and shows how different this artist’s approach was to Bernard’s. Painted in a single session, this small painting displays Van Gogh’s varied brushwork and echoing use of color. The orange reflection in the river is echoed by the underside of the bridge but also by orange dots in the tree above, the figures on the bridge, some of the roofs, and more orange reflections near the far bank of the river. The pink strokes in the sky are echoed by pink strokes on the bridge supports and in the water at the lower right. Working quickly, Van Gogh paid little attention to perspective and proportion, which is clear from the suddenly shrunken bridge supports beyond the first and the larger scale of the figures on the bridge compared to those in boats. Still, the energy of the colors and brushwork holds the viewer’s attention.

Gasometers at Clichy by Paul Signac, for me, is one of the best works in the exhibition with its composition of contrasting curves and rectangles, varied brushwork, and harmonious color balance. The painting emphasizes the natural gas plant in Clichy without interjecting leisure activities or the natural beauty seen in other paintings in the exhibition. For his contemporaries, the idea of Clichy as an industrial center would have been commonplace but focusing on this as his subject would have been surprising. Railroads, bridges, and smokestacks had appeared in idyllic Impressionist paintings for several decades, but to focus on an industrial site was likely seen as an inappropriate choice by the artist. Signac’s approach to Neo-Impressionism was bolder than Seurat’s or Angrand’s. His brighter color and larger brushstrokes were very influential on Van Gogh in this period and the two artists were close friends until Van Gogh’s death. Signac, along with Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, was vociferous in defending Van Gogh’s works against another artist’s criticism in 1890. Lautrec even challenged the offender to a duel and Signac said he would step in if Lautrec were to be killed. Fortunately, the offender apologized and no duel occurred.

Van Gogh’s Factories at Clichy focuses on Clichy’s industrial nature but unlike Signac, he adds an empty field and a pair of figures between the viewer and the buildings, providing a contrast between the rural and industrial areas of Clichy. There’s no sense of judgment of the smoke-spewing factories in this or any of the exhibition’s works. The factories, trains, and bridges are simply part of the modern landscape. In this work, the factories also add a dramatic color contrast to the green field and blue-green sky. The application of paint also varies in each band of the composition. The field is filled with distinct dashes and dots and the buildings are a mix of smaller dots, shorter strokes, and patches of color. The sky is mostly blended color overlaid with squiggles and dots of smoke from the factories. I found the contrast almost symbolic; the blended sky is more Impressionist but it’s being invaded by Van Gogh’s more dramatic Post-Impressionist style.

Learn more about the context of the works in the exhibition in this video from the Art Institute of Chicago.

Vincent Van Gogh had moved to Paris in 1886 to improve his painting and to learn more about the newest artistic movements, the avant-garde. His first encounter was with Impressionism; the works of Claude Monet and others encouraged him to use brighter colors than he had previously. However, it was his encounters with the artists in this exhibition that introduced him to the use of visible brushwork. Though inspired by the pointillism of his Neo-Impressionist friends, he quickly moved toward the expressive brushstrokes and saturated colors that would dominate his later works. “Van Gogh and the Avant-garde: The Modern Landscape” continues through Labor Day, September 4. For fans of Van Gogh and other Post-Impressionists, it is well worth visiting.

The Art Institute of Chicago is located at the corner of South Michigan Avenue and East Monroe Street in Chicago, Illinois. The museum is open from 11 to 5 on Friday through Monday and from 11 to 8 on Thursday. It is closed on Tuesday and Wednesday.

It is amazing what one can see in a work of art when well trained and, most important, sensitive eyes guide you in the process.

Oh!! My 👩🎓 alma mater - I shall visit again 🔜