A photograph is about, not just of. — Abelardo Morell

In this edition of Chance Encounters, I’m looking at the work of my favorite contemporary photographer, Abelardo Morell. In the mid 1990s, I first encountered reproductions of Morell’s photographs when I was looking for images to help my students understand the camera obscura. I was charmed by his works and then in 2013 I had the good fortune to see his retrospective exhibition “The Universe Next Door” at the Art Institute of Chicago and I was blown away by the artist’s inventive, absorbing array of works.

Abelardo Morell was born in Cuba in 1948, arriving in the United States at the age of 13 when his family fled the Cuban Revolution. His earliest photographs were typical snapshots of family and New York City taken with a Brownie camera. Inspired by his first photography professor’s open-minded approach of encouraging students to explore literary and personal inspiration, Morell began to contemplate a career in photography. He took a break from his studies for several years to explore the possibilities of such a career. After completing his undergraduate degree at Bowdoin College, he attended Yale for an MFA in photography. His focus in this period was street photography.

The birth of Morell’s first child inspired a new approach to his photography. Needing to stay closer to home and spending time with his son, for whom everything was new and surprising, led Morell to create photographs that expressed the wonder of the everyday. Lisa and Brady Behind Glass, above, depicts his wife and son behind pebbled glass and represents the more personal environment in which the artist began to work. Morell felt this work was probably out of step with the artistic values of his former graduate program at Yale and the New York art world because of its personal, emotional subject. The pebbled texture of the glass blurs the figures, making them appear as apparitions of another reality. Morell had begun to explore creating optical effects while maintaining his commitment to showing what the camera records.

I started making photographs as if I were a child myself. This strategy got me to look at things around me more closely, more slowly and from a vantage point I hadn’t considered before. This way of seeing changed me and my photography.

In 1996, Morell was invited to create illustrations for a new edition of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The series of images he created was part of his series exploring the physicality of books, begun in the mid 90s and continuing into the 21st century. It Was Much Pleasanter At Home is an example of his use of books to create architectural compositions, a feature of works in the books series. To illustrate the surreal adventures of Alice, Morell cut out reproductions of John Tenniel’s characters from the original 1865 edition and used these as actors in settings made of books, plants, and water. In this illustration, large Alice is cramped by the book ceiling and wall, yet reaches between the pages to grasp the fleeing White Rabbit. The tone of the photograph matches the novel’s whimsical but slightly scary events.

I think that a lot of what I am after is to create little theaters where fabulous things may happen. I’m interested in the way limitations can sometimes become springboards to freedom. It is this conviction that drives much of my work in general.

Morell’s inventiveness in creating images is demonstrated by Still Life with Pears. This work is a photogram, a photograph made without a camera and is an example of the artist’s fascination with early forms of photography. The first permanent photograms were made in the 1830s by Henry Fox Talbot. Talbot called his images “photogenic drawings” and made them by placing objects on light sensitive paper which was then exposed to bright sunlight. Ever since, some form of light sensitive paper has been the standard material for creating photograms, resulting in a single unique image. Morell wanted to find a way to get the same effect with a film negative so he could enlarge his images and make multiple prints as he could with conventional photography. Using 8 x 10 inch film, the artist placed a variety of clear and opaque objects which interact with the light in complex and interesting ways. At first glance, we seem to be looking at a still life arrangement on a glass tabletop but certain aspects of the composition challenge that interpretation. The fork, spoon, vine, and even one of the pears seem to pierce the tabletop. It’s only when we remember that this was made by placing objects directly on the film that the anomalies make sense.

Morell’s interest in still life extends beyond the photograms. In a series of photographs of glass or ceramic arrangements created in 2019 and 2020, the artist explored the interaction of light, surface, and color. Glassware Vertical Still Life Against Ochre Wall depicts an arrangement of clear glass objects crowded together on a light brown surface against an intensely colored wall. The contrast of the surface and wall is emphasized by the interaction of the colors with the glassware. By placing smaller glasses inside larger vessels, Morell multiplied and complicated the layers of reflection. Still life was one of the first subjects to become popular in photography after its invention in the 19th century. This was partly a practical choice; early photographic techniques required lengthy exposure times, often stretching to hours, difficult for living subjects to endure. Also, of course, still life had been a subject for painters since ancient times, used as displays of wealth or exercises in depicting varied textures, colors, and shapes. For Morell, creating still life arrangements feels like creating brand new worlds where new formal and conceptual possibilities can be explored.

This picture gave me the feeling that photography is in many ways still raw and unexplored. Making this picture was for me a way to rediscover the mystery of the medium and maybe to share it with others.

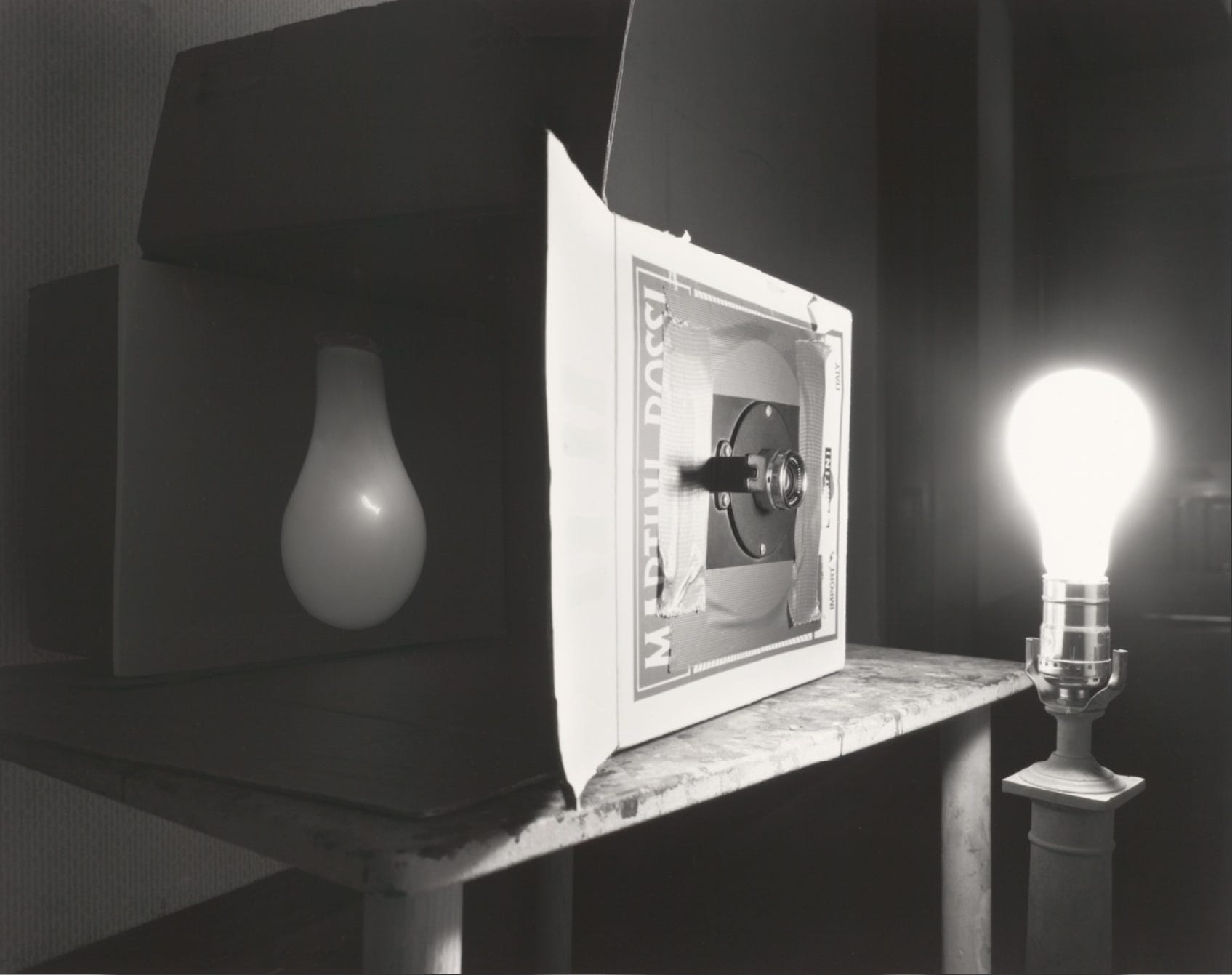

In 1991, while teaching the rudiments of photography to his students at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, Morell put together a basic camera obscura. The photograph Light Bulb depicts the device he created. A camera obscura (Latin for “dark chamber”) is made by cutting a small hole in a wall through which light outside enters a darkened space. An image of any object outside the dark space will be projected onto the wall opposite the hole, but will appear upside down. A lens can be inserted into the hole, as Morell did in his, to sharpen the image. This optical device was discussed in writings from ancient China and Greece but Leonardo da Vinci wrote the clearest description of it early in the 16th century and European artists were using the camera obscura as an aid to drawing from then on. To use a camera obscura as a drawing aid, one traces the projected image.

The notice Light Bulb attracted for Morell led him to explore the device further. In the summer of 1991, Morell began to play with the creation of camera obscuras by covering windows in his house with lightproof plastic. The effect was to project images of his neighborhood upside down on the walls of his bedroom, living room, and his son’s bedroom. At first Morell couldn’t work out how to create photographs of these effects; they were simply family fun. Eventually he began to try to capture his rooms in black and white photographs. The exposure times were very long, sometimes as much as 8 hours, but the photographs created an uncanny blending of indoors and out, private and public, and of course right side up and upside down. It was one of these images that was my first encounter with Abelardo Morell’s art.

That summer I felt I had touched on something very important: that the very basics of photography could be potent and strange.

For the next fourteen years, Morell continued taking black and white camera obscura images while also exploring other projects including the Alice illustrations and his books photographs. In 2005, Morell took the leap to color photography, though he continued using black and white for some works. At the same time he made changes to his camera obscura setup, to shorten exposure times and to improve focus and light sensitivity. Then in 2006 and 2007, the artist visited Venice where he created color images of that unique city. In Santa Maria della Salute in Palazzo Bedroom, we see the image of the church as projected by the camera obscura on the wallpaper. The ornate church is echoed by elements of the room’s decoration – the wall paper pattern, the mirror, and a 17th century black and white engraving of the church itself which is covered by the projected image. The latter is an example of touches of humor that can sometimes be found by looking closely at Morell’s images.

View of Lower Manhattan, Sunrise is an example of a less busy camera obscura composition. Morell had been capturing camera obscura images of New York since 1994, but in the series to which this photo belongs the artist was recording the view at different times of day. This photograph contrasts the very early morning light of the projected city with the warm yellow light coming around the edges of a door. We can see from this that Morell’s camera obscura and digital camera setup was by this time capable of capturing very subtle effects of light and color as well as the precise details of even a distant outside scene.

Having to work to earn a certain kind of image feels right. If it comes too easy, it might be suspect.

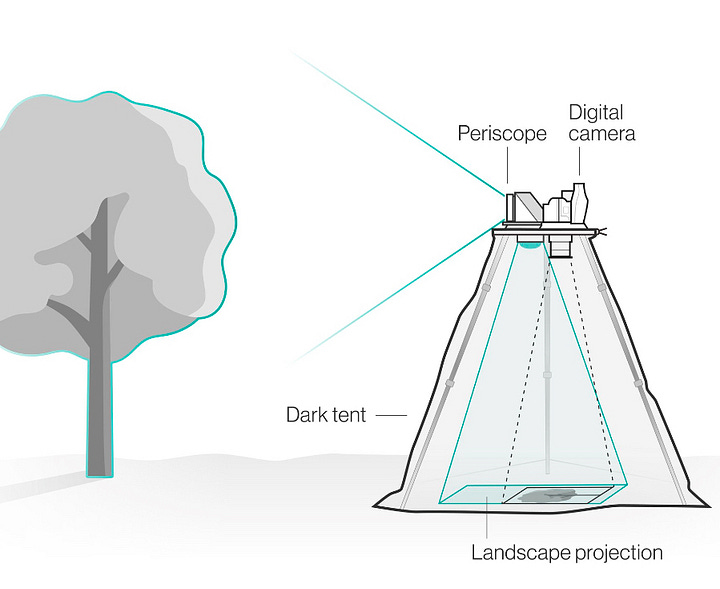

The artist desired to move his camera obscura approach out of doors. Morell’s tent camera utilized a periscope to project a view from outside onto the ground inside a lightproof tent and a camera to capture the projected image. Tents had been designed to create portable camera obscuras in the late 16th century and used in the 17th and 18th centuries. Morell used his first tent design in 2010 to take photographs of mountain scenery in the American West. Since then he has refined the design of the tent until it has come to the form seen in the diagram and photograph above.

In this second view of New York City, we can see striking results of Morell’s tent camera photography. Projected onto a rough wooden floor on the roof of 512 West 22nd Street is a view of deep red brick buildings across the street with the more distant view of the Empire State Building beyond them. The combination of the blue sky and the visible wood grain is unexpected, but carries out Morell’s idea that his tent images produce “a rather wonderful sandwich of two outdoor realities coming together.” The wood grain also has the effect of making the dark red buildings appear to waver as if seen through water or a heat mirage.

The last image for this edition is one of Morell’s most recent, from a series of tent camera images taken in landscapes associated with the great Impressionist painter Claude Monet. Poppy Field #1, near Vétheuil, France was created in one of places where Monet had lived and painted and captures a favorite theme of the painter. Morell’s photograph plays with art history on many levels. The 1860s and 70s when the Impressionists first appeared in the Parisian art world is also the period when photography took off. The pebble-scattered surface below the tent fractures the projected image so that it has the painterly rough edges of an Impressionist painting. The path leading into the projected landscape is a common pictorial device of Monet and his Impressionist colleagues as well.

Morell is not the only contemporary photographer who has turned to artisanal 19th century techniques. For some it is a way of rejecting digital technologies but for others, including Morell, it is a return to the origins of photography. Most of all though, Morell is interested in exploring what can be thrilling in contemporary photography. I’ve been able to include only a tiny selection from over 40 years of Morell’s photographs. I encourage you to explore more of his work, much of which you can see at the artist’s website (https://www.abelardomorell.net/)

“Abelardo Morell: New Ground – In the Terrain of Van Gogh and Monet” is on exhibit until Saturday, December 9 at Edwynn Houk Gallery, 745 Fifth Avenue, New York City. https://www.houkgallery.com/exhibitions/100-abelardo-morell-new-ground-in-the-terrain-of-van-gogh-and-monet/works/

Thank you! I always learn from reading this interesting blog. Camera obscura, dreamlike and magical as Morell said in the video!