How do you respond when you are confronted with a work of art that you don’t understand? In this edition, my subject is Abstract Expressionism, an art movement of the mid-20th century that continues to provoke expressions of disgust and dismay over 70 years later. I won’t try to make you like these works. Instead I hope to provide you with an understanding of what these artists were doing and some ideas about approaching art that doesn’t immediately appeal to you.

In the early 1980s I was fortunate to earn a National Endowment for the Arts internship in the Museum Education Department of the Art Institute of Chicago. One of my responsibilities was giving public tours. The lecturers would propose topics for the daily tour and a monthly calendar would be created. Naturally everyone chose topics in which they were interested and with which they felt comfortable. Occasionally an illness or emergency would mean a colleague was needed to fill in on a scheduled topic. On one memorable occasion, about two weeks ahead of his scheduled talk on Abstract Expressionism, my colleague had a family emergency and I was asked to take over his talk. I had never studied the topic and I was in a panic. I didn’t even know if I liked any of the paintings. Despite my qualms, I had to present these works to the public, so I set out to learn about the art very quickly. My colleague walked through the gallery with me while I took frantic notes, then I spent two weeks reading as much as I could.

One lesson I gained from this experience is that understanding the who, what, when, where, and, most importantly, why of an artwork sets me on a road to appreciating what the artist has created. Since then, learning more about it is my first reaction when I encounter art that I’m unfamiliar with or art that doesn’t immediately appeal to me. Sometimes I realize that I like, or even love, what I’m looking at and sometimes I discover that I don’t and probably never will, like it.

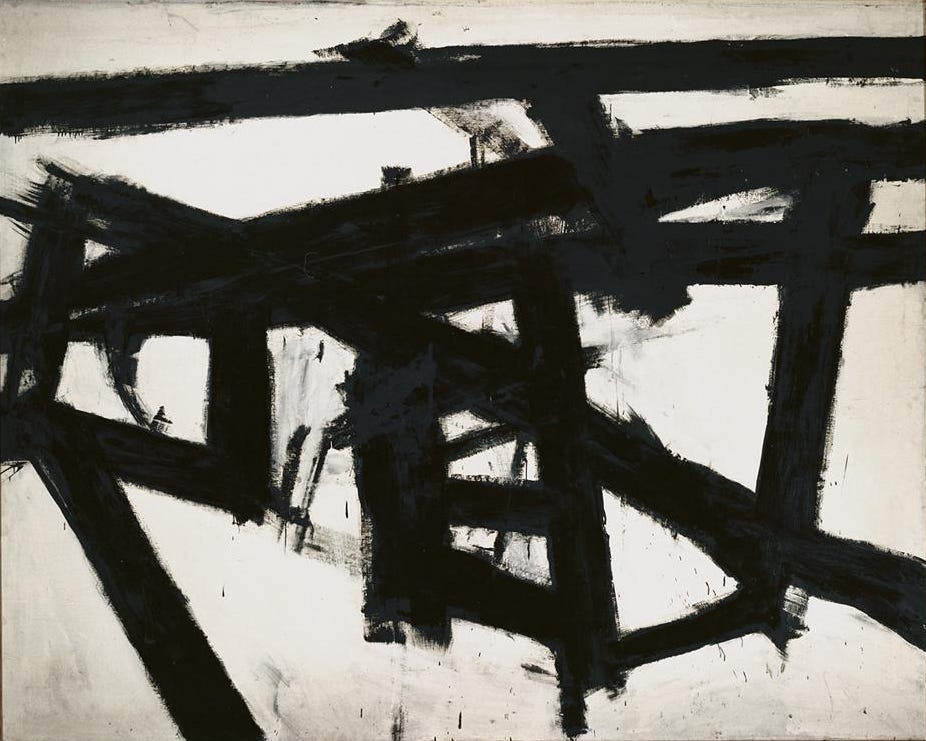

In the case of Abstract Expressionism, as I studied I was drawn to the art of Franz Kline (American, 1910 – 1962), whose 1956 painting Mahoning is reproduced above. Though in a very different context and on a different scale, the big brushstrokes in black and white reminded me of studying Chinese and Japanese ink painting and calligraphy. Kline is best known for large black and white paintings like Mahoning, which is 6 feet 8 inches by 8 feet 4 inches. This large scale is a characteristic of nearly all works of Abstract Expressionism. A brief description of Kline’s paintings might be black brush strokes on white, but that oversimplifies the work. Kline considered the white areas as important as the black and observation of Mahoning will show areas where white has been painted over black. The artist was striving to create a balance of black and white within a dynamic composition filled with diagonals. A sense of spontaneity is created by the large house painter’s brushes that the artist preferred and by the presence of drips and spatters.

Influenced by Surrealism and the idea of automatic drawing (making marks without prior planning), Kline would create sketches by painting with opaque black watercolor on paper, often using pages from old phone books. Like the Surrealists, Kline believed that this technique allowed his subconscious mind to participate in his art. After creating the sketch, Kline would look to see if he was reminded of anything by the marks he’d made; if so, he would identify the reference with the title of the work. Mahoning is the name of several townships and waterways in northeastern Pennsylvania where the artist grew up. This sketching process belies by the sense of spontaneity in the large final version of Kline’s work, and if you compare the sketch with the finished work, you will see how Kline adjusted the sketch to remove horizontals and replace them with diagonals, adding instability to the collection of lines.

Mark Rothko (American, 1903 – 1970) is also an Abstract Expressionist artist, yet his works look nothing like Franz Kline’s. How can such different looking paintings both fit into Abstract Expressionism?

An artistic movement that evolved in New York City, Abstract Expressionism was a dominant force in the art world from the 1940s through the 1960s and continues to influence and inspire artists even today. The first major artistic movement to originate in the United States and spread to Europe, Abstract Expressionism emphasized the artist's relationship with and use of physical materials. In content or subject matter, many of the artists were interested in uncovering the unconscious, through psychoanalysis and through their art. Freedom was a major theme, freedom of gesture, of color, and of form. The works are large to create an environment which surrounds or even overpowers the viewer. Another reason for creating large works was an idea which goes back to the Renaissance: a big painting is an important painting. Throughout the Modern Period, artists who wished to assert the importance of their artistic philosophy created large paintings, for example Édouard Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass (1863). (See Chance Encounters, Edition 5 for more about this painting.)

At a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act. What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event. – art critic Harold Rosenberg (American, 1906 – 1978)

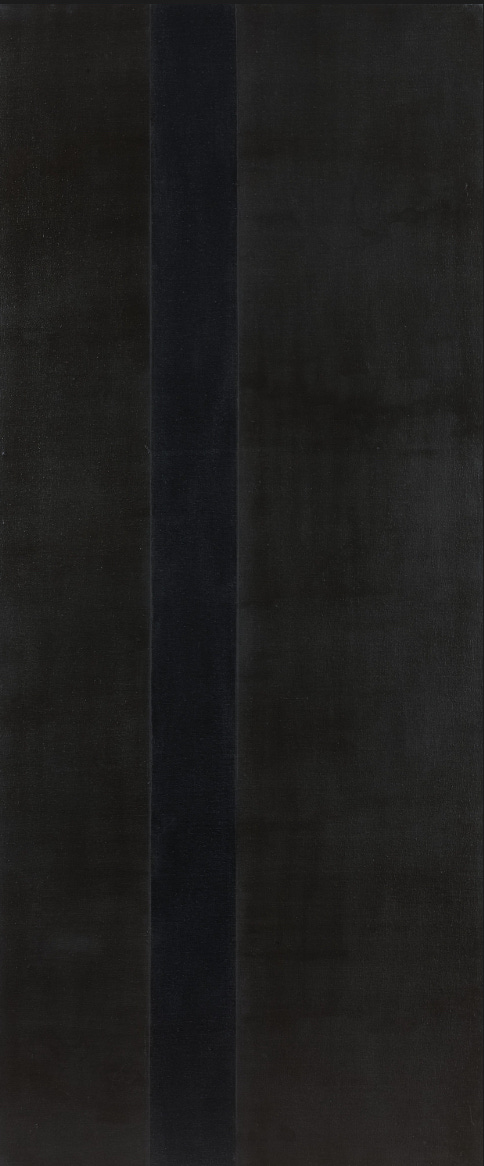

The emphasis on personal expression means that there are a wide variety of individual techniques and styles within the movement, as the comparison between Kline and Rothko shows. There were two major aspects or subdivisions in Abstract Expressionism – Action Painting and Color Field Painting. Franz Kline is an example of Action Painting; these artists were especially using the canvas as an arena, as Rosenberg described. Kline used assertive bodily action to create his large works and the paintings became records of their own creation. Mark Rothko was the quintessential Color Field painter. The Color Field artists stressed masses of color, whether brushy and blurred as in Rothko’s Lavender and Mulberry (above), or more dense and constrained as in Barnett Newman’s (American, 1905 – 1970) paintings. (see below)

In the 1940s, Mark Rothko was one of a group of artists in New York City who were struggling to define and establish the goals of what is now called the Abstract Expressionist movement. Rothko's signature style was developed in the 1950s, saturating the canvas in layered colors, where colored rectangles appear to hover above a field of another color. The blurred edges create an atmospheric effect into which the viewer can become absorbed. As with Franz Kline, I was drawn to Rothko’s visual form first and only understood his goals after looking and learning more. (See Chance Encounters, Edition 10 “Rothko: The Power of Color” for more about this artist.)

The primary sources of Abstract Expressionism are found in the earlier 20th century movements Expressionism and Surrealism. Obviously Abstract Expressionism and Expressionism share a name but what did that mean for the young artists of the American movement? Expressionism, an international movement which began in the 1910s, stressed the emotional power of color and abstract forms to convey meaning. Of the Expressionists, perhaps the most significant for the new movement was Vasily Kandinsky (Russian-French, 1866 – 1944). Though not all Expressionist works were non-representational, Kandinsky was one of the pioneers of such art. Improvisation 28 (second version) is an example of Kandinsky’s use of spontaneous creation which inspired many Abstract Expressionists. The underlying philosophy of Kandinsky’s art was his belief that the purpose or proper content of art was the artist’s inner or spiritual reality. His publication of his philosophies of artistic form and meaning provided the American artists to learn of his ideas.

Surrealism, which developed in Europe in the 1920s, was also important to the development of Abstract Expressionism, not just for its ideas but for its practitioners, many of whom fled World War Two and arrived in New York City in the early 1940s. Several of the young American artists worked for émigré artists as translators and studio assistants. One of these Europeans, Max Ernst (German-American-French, 1891 – 1976), was a prominent Surrealist who invented frottage and grattage, innovative techniques for creating texture in drawing and painting. Frottage is making rubbings and incorporating them into a drawing while grattage involved scraping paint across a canvas under which a textured object lay. Fishbone Forest above, is an excellent example of the latter technique. Ernst’s experimental approach to his materials, the Surrealists’ interest in the influence of the subconscious on creativity, and personal contacts with Europeans artists influenced many of the Abstract Expressionists.

A central figure of Abstract Expressionism, Jackson Pollock (American, 1912 – 1956) was one of the foremost advocates of the idea of painting as a record of the action of making it. Pollock’s approach to Action Painting was the drip technique, in which the artist spread canvas on the floor and dripped and splattered paint on the fabric from above. The result is a web of paint which reflects the motion of the artist's whole body: walking around, stepping across and sometimes on, swaying around and over the canvas. In this video, filmed by Hans Namuth (German-American, 1915 – 1990), we see and hear Pollock at work.

For Pollock, the goal was a wholly spontaneous expression of the artist's personality through unplanned creation. Convergence may be the best Pollock painting to look at in reproduction. The larger patches of paint and bright colors are easier to see than the more delicate threads of paint in many of his works. As can be seen in Namuth’s film, both intuition and accident played a role in Pollock’s process but the artist also depended on his long experience with and knowledge of his materials. He knew what would happen when he poured from a can or cup as opposed to how the paint would fall from a stick or brush.

Pollock's technique emphasizes the liquid nature of his paint. Even when the paint has long been dry, the sense of its liquidity remains. These detail photographs from Convergence give you a sense of the variety of effects Pollock could create. Notice how the wet colors flowed and blended into each other at times while in other places a color had been allowed to dry before a new color was applied. For me, one of the pleasures of Action Painting is trying to reconstruct what movements resulted in the painting’s appearance. Many who disapprove of Pollock’s approach feel that anyone could create a painting in this way. What I have seen, though, is that even when someone was able to create a visually compelling work using Pollock’s technique, their work doesn’t look like Pollock’s. In this sense, drip technique is simply another method of painting and each practitioner achieves their own effects, their own personal style, by using it.

Barnett Newman (American, 1906 – 1965) was a Color Field painter whose works are characterized by a colored background with a band or bands of contrasting color. Newman termed these bands “zips” and from their introduction in 1948 they were a constant presence in his paintings and were even translated by him into three dimensions as sculptures. One might think that such a simple device would become repetitious but by varying his colors and their density, shifting the position of the zip in the composition, and changing the size of his canvases, Newman created great variety within his body of work. In spite of their simple, non-representational form, Newman’s paintings frequently bear titles which reference metaphysical and spiritual themes. Abraham refers to the Old Testament patriarch, but Abraham was also the name of Newman’s father who had died two years earlier. Almost 7 feet tall but less than three feet wide, the painting’s dimensions mimic the size of a tall man but the dark colors create a void-like presence, especially when seen from a distance. The similarity of color between the zip and its background requires close attention. Newman saw his approach as a new beginning for painting, with pure abstraction (or non-representational form) a new language for the expression of his ideas.

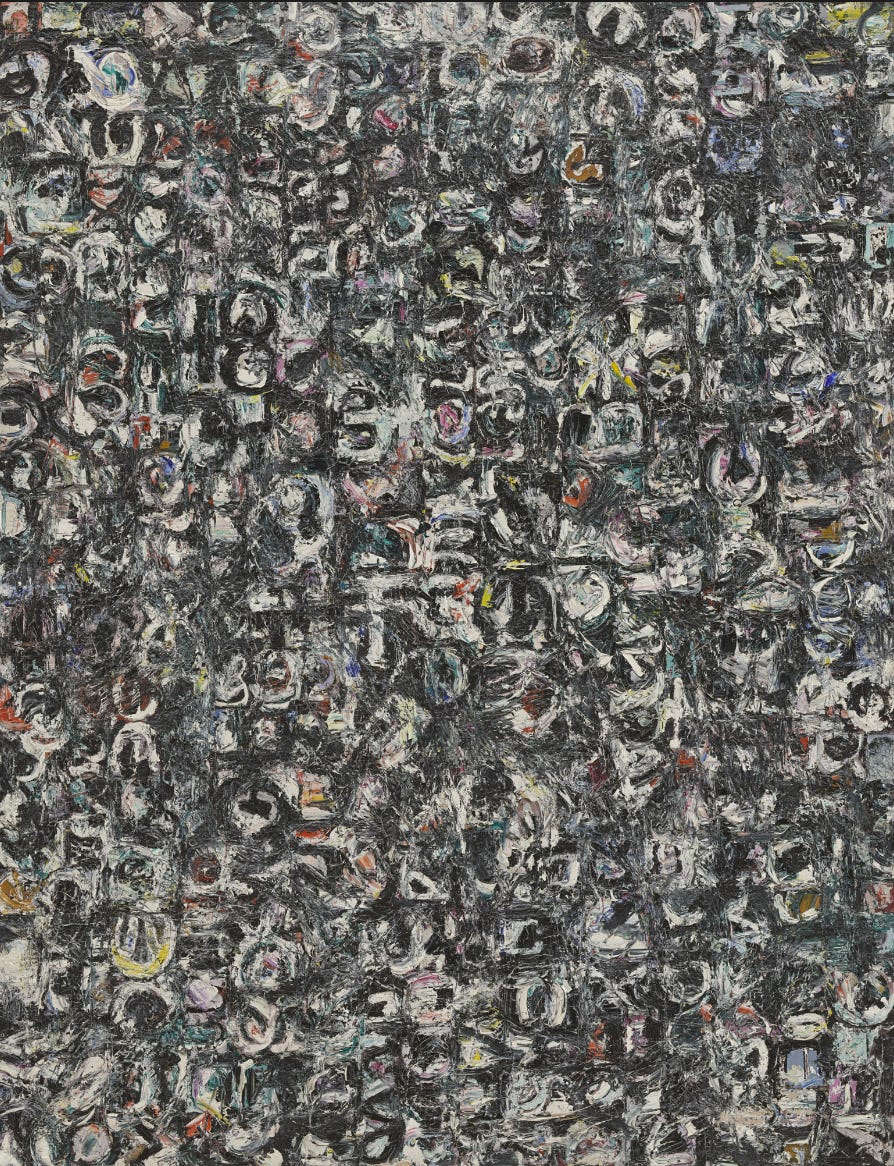

There were women among the founders of Abstract Expressionism, though at the time, they received considerably less attention than their male colleagues. That neglect continued until very recently when exhibitions and publications have examined their contributions to the movement and their individual achievements. Lee Krasner (American, 1908 – 1984) was an important member of the group as well as the wife of Jackson Pollock. Krasner’s works during the period of her marriage were often smaller than typical works of other Abstract Expressionists. She worked flat on a tabletop which naturally limited the size of her works, but she also created densely worked surfaces better suited to a smaller canvas. This untitled painting from 1949 is part of Krasner’s series called Little Images, about 40 works created between 1946 and 1949. Though smaller in scale, the repetitive strokes and thick paint tie this work to Action Painting. Krasner had a strong interest in languages and alphabets which influenced many of the works in the series. The shapes and marks in this painting look like characters from a lost language; one feels that there is a meaning to be deciphered but one lacks the key to the puzzle. For Krasner, this work was connected to her childhood when she had copied the Hebrew alphabet though she couldn’t read the language. Connecting art’s meaning to memory and emotion was one of the ideas that the Abstract Expressionists adopted from both Expressionism and Surrealism.

Though nearly all Abstract Expressionists created non-representational paintings exclusively, there were some artists who created recognizable images. Willem de Kooning (Dutch-American, 1904 – 1997) is the best-known of these artists, due in large part to his infamous images of women. In the late 1940s, de Kooning joined forces with Pollock, Kline and others in their quest to break free of earlier styles and develop this new American style. De Kooning’s approach in Woman I is Action Painting, but instead of the overall compositions typical of Pollock’s work or the purely abstract black and white designs of Kline, de Kooning constructed the figure of a rather monstrous-looking female figure with his slashing brushstrokes. Beginning in 1950, the artist worked on this canvas for two years, scraping it down, starting over many times before he considered it finished. Some of the supporters of the non-representational approach chastised de Kooning for “regressing” to such a traditional subject but the artist kept creating his images of women, proclaiming that “flesh is what oil paint was invented for.” Other critics have found Woman I misogynistic because of her monstrous appearance, but de Kooning responded that he found the grotesque “joyous.” This painting is a case when knowing more helps me understand it, but it doesn’t help me like it. De Kooning also created non-representational works which are more like what one expects from an Abstract Expressionist artist.

The underlying emphasis on artistic freedom in Abstract Expressionism and other Modern American movements led the US State Department and later, the Central Intelligence Agency to promote American Modernist art generally and Abstract Expressionism specifically. In international exhibitions like the “Masterpieces of Modern Art” Festival in Paris, France in 1952 and the United States Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal, Canada, the government and the Museum of Modern Art along with other prominent museums used art to highlight the contrast between American culture and the Soviet Union and other totalitarian governments.

As long as our artists are free to create with sincerity and conviction, there will be healthy controversy and progress in art. How different it is in tyranny. When artists are made the slaves and tools of the state; when artists become the chief propagandists of a cause, progress is arrested and creation and genius are destroyed. – President Dwight Eisenhower, 1954

It's important to note here that the artists created the innovative work and the US government latched onto it for its own political purposes. Many voices in the country, from Congressmen to conservative media outlets, objected to the government openly funding the purchase or exhibition of avant garde art. In contrast to Eisenhower, Harry Truman, while president, described Modern art as “merely the vaporings of half-baked lazy people.”

Maybe you agree with President Truman, but there’s no denying the importance of Abstract Expressionism in the history of art. These artists, almost all young and American-born, were frustrated by the long-standing perception of American art as lagging behind European art in innovation. One of the goals they achieved was to create an American art style that would be influential in Europe. Though they were influenced by some earlier European styles, many of their ideas and techniques were new. The Abstract Expressionist artists expanded the definition of art and opened new avenues of creation for the artists who came after them.

Do you feel you have a better understanding of these artists and the Abstract Expressionist movement? Have these works and my explanations won you over or made you feel there might be something in this movement for you to explore further? Please share your ideas on these questions and Abstract Expressionism in the comments.

This is a wonderful post in more ways than I can name, though I will offer up at least a few:

>Your personal story of how you came to engage with Abstract Expressionism is a marvelous entry point: giving us all permission to try it out without having to commit, and knowing it is OK to decide some works do not connect, while leaving plenty of room to find others that do.

>the comparison of the Kline sketch with the finished painting, along with your observations on how he worked, were illuminating. The final seems to me more balanced and carries itself more lightly, none of which would have been apparent if each were viewed separately.

>I only recently ran across Max Ernest’s Fishbone Forest. I liked it immediately (and I’m aware that its accessibility to me may well have had to do with its representational aspect), but how interesting to learn of the techniques he used and their relationship to Abstract Expressionism.

>I appreciated very much your observations that Pollock, valued both intuition and accident, but also that “the artist also depended on his long experience with and knowledge of his materials. He knew what would happen when he poured from a can or cup as opposed to how the paint would fall from a stick or brush.” It is easy to overlook that intuition, particularly, is enriched by skill and experience. I have always felt Pollock was overhyped, and I still think that, but at the same time, what I see is that part of the problem may be that the hype overlooks the skill and experience he brought to his work.

>the Krasner appealed to me from the first time I viewed it at MOMA, but you have nonetheless added a marvelous dimension to my appreciation of the work with these observations: “The shapes and marks in this painting look like characters from a lost language; one feels that there is a meaning to be deciphered but one lacks the key to the puzzle. For Krasner, this work was connected to her childhood when she had copied the Hebrew alphabet though she couldn’t read the language.”

>I also enjoyed your note on the historical context, which is complicated and intriguing.

As a side note, the artist who had the most to do with my own wish to try and engage with Abstract Expressionism, foreign though it felt, was Louise Fishman. On examining her work alongside more famous Abstract Expressionist works, I am at a loss as to why her work isn’t further up in the recognized pantheon. I don’t know whether her work is familiar to you, but if so, I’d be interested in your view.

Thank you so much for this excellent post and your invitation to engage with this art.

Thank you for writing this.