In this edition of Chance Encounters, I have chosen another subject that viewers often find challenging, the artist Wassily Kandinsky (Russian-French, 1866 – 1944) and his role in the rise of pure abstraction. Before discussing this artist and his works, I wanted to define some of the terms I’ll be using here. Representational art refers to works in which objects from the real world can be recognized. Representational art can be naturalistic, that is, imitative of real world appearances, or abstract, which is simplified or distorted from real world appearances. When the artist makes no reference to real world appearances, we can use the terms non-representational or non-objective. The latter term was coined by Kandinsky. Another way of describing such art is to call it pure or complete abstraction.

Abstract and non-representational art rewards the viewer who takes some extra time to look at and think about what they see. Before (or after) you read what I have to say, you might find it useful to look at the images alone. Click on any image to open a slideshow of the images. If you do this from the email, it will open the Substack app or website.

Must we not then renounce the object altogether, throw it to the winds and instead lay bare the purely abstract? – Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, 1911

Video: Creative Hands (Schaffende Hände), 1929 by Hans Cürlis

Wassily Kandinsky was one of the leaders of the early 20th century development of abstract and non-representational art. Though he is sometimes described as the first artist to create a non-objective painting, many European artists working in the second decade of the 20th century, including Hilma af Klint, Robert Delaunay, Piet Mondrian, and Sonia Delaunay, experimented with extreme abstraction, including non-representational imagery. Kandinsky and many other artists were in search of a new artistic language which would allow them to express new spiritual, scientific, and aesthetic concepts.

Improvisation XIV (above) was painted in 1910, as Kandinsky was working his way from representational art toward the purely abstract form that would occupy him for the majority of his career. Within the masses of color, we can see a stylized pine tree at the left and two abstract figures riding vaguely horse-like shapes toward one another. To a viewer unfamiliar with Kandinsky’s earlier works, interpreting these shapes as riders on horseback may seem a bit of a stretch. I was skeptical the first time I read this interpretation, too. However this theme of the horse and rider reoccurs throughout the early phases of the artist’s career, and after seeing how often Kandinsky returned to it, reading these shapes as riders makes sense to me. However, this is just one interpretation and many others are possible. For example, contesting forces, expressed by shapes and colors to the left and right in this painting, appear in many of Kandinsky’s works, especially in the years before and during World War One. Based in Germany at this time, Kandinsky and his fellow artists were acutely aware of the social, economic, and political stresses of the time and they sought, in various ways, to express their anxieties in their art. Many viewers of non-representational art are frustrated by the absence of a single, obvious meaning. This is a deliberate choice of artists like Kandinsky who are leaving their works open to the viewer’s ideas, feelings, and interpretations.

Born in Odessa, then part of the Russian Empire, Kandinsky trained in law and economics at university and then became a lecturer in jurisprudence at the University of Moscow. Just a few years later, though, he abandoned his legal career and moved to Munich, Germany, to apply to the art academy there. Kandinsky’s earliest works were life-like landscapes like Odessa: Port. The artist used mathematical perspective to define the pier and skillfully applied color to depict sea and sky and give all of the objects a convincing reality. A painting like this reflects traditional European artistic training including some methods which dated back to the 15th century. Kandinsky’s first response to seeing less traditional art was a sense of shock and discomfort. Before leaving Russia in 1896, Kandinsky visited an exhibition of French Impressionist painting, including Grainstacks by Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926). In this series of rural landscapes Monet captured the effects of the seasons and weather, often dissolving the piles of grain in light and color. Kandinsky wrote

That it was a haystack the catalogue informed me. I could not recognize it. This non-recognition was painful to me. I considered that the painter had no right to paint indistinctly. I dully felt that the object of the painting was missing. And I noticed with surprise and confusion that the picture not only gripped me, but impressed itself ineradicably on my memory. — Wassily Kandinsky

Many of us have felt like this when confronted by art which challenges our expectations. How dare the artist (and by extension, the museums and the critics) foist this confusing mess upon us? How unexpected that someone who reacted this way to Monet would turn out to be a powerful proponent of a radical art that moves far beyond Impressionism. However, having digested Monet’s lessons, Kandinsky soon moved into a more impressionistic style, with an emphasis on light and color and visible brushwork. He also tried out a decorative symbolist style and one derived from Fauvism. At this point in his career, the artist was changing styles quickly as he traveled around Europe discovering avant garde art and ideas.

German cities at the turn of the century were hotbeds of new artistic ideas. Inspired by exhibitions of Post-Impressionist and Symbolist art from France and Secessionist art from Vienna, a new artistic movement was developing. Now known as Expressionism, it was characterized by artistic freedom, vivid color, and painterly form. Expressionist groups were organized in many German cities. Aged 30, Kandinsky was older than his artist-classmates in Munich, but he quickly found like-minded progressives with whom he participated in formal and informal artistic groups. The most influential of the groups Kandinsky helped establish was Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), founded in 1911. The Blue Rider created a publication in which Kandinsky and co-founder Franz Marc (German, 1880-1916) published their theories and images. They also held traveling exhibitions in which they displayed their own art and that of others they saw as sympathetic to their theories. The group had no common style but shared the belief in art as a means of direct communication from the heart of the artist to the soul of the viewer. Unfortunately, the advent of World War One broke up the Blue Rider, as Marc and other associates entered the German army and Kandinsky was forced to return to Russia.

Lyrical was painted in 1911, an extremely important year for Kandinsky. In addition to the founding of the Blue Rider, this was the year in which Kandinsky published Concerning the Spiritual in Art, the first of his two theoretical treatises. This painting clearly depicts the horse and rider theme which was so important to Kandinsky, but it also includes the outlines and patches of color seen in Improvisation XIV, dated a year earlier. In his treatise, Kandinsky divides his approach into three categories of painting which he called Impressions, Improvisations, Compositions. Lyrical falls into the Impressions category; these works started from the artist’s external reality, from observation of the real world and often maintained recognizable references to their inspirations. One of the most important categories for Kandinsky was the Improvisations, which include not only the works so titled and numbered, as Improvisation XIV is, but other works with a similar character, that is, extremely painterly form, sprawling black outlines, and the appearance of spontaneity. Both the Improvisations and the final category, Compositions, depicted images which Kandinsky believed emerged from his unconscious. The difference between the two was in the formality of the design. The Compositions have geometric shapes and sharp lines drawn using straight-edges and compasses as well as more carefully structured layouts.

Kandinsky’s shift to pure abstraction or non-objective art occurred in the years between 1910 and 1912. The artist said that as he walked into his own studio one evening he saw a painting which he didn’t recognize. He didn’t realize it was his own work hanging upside down, but its oddity intrigued him. This, he claimed, encouraged him to move toward greater abstraction. Improvisation 28 has the sense of spontaneity and energy that Kandinsky’s Improvisations often express. Several details of this work are recurring motifs in the artist’s works, including colorful circles, undulating lines, curves combined with spiky eyelash-like lines, and groups of parallel lines. Viewers of this work have described it as a scene of war and peace. Conflict consumes the left two-thirds of the composition while, at the right edge, more white and fewer dark color patches might be interpreted as a peaceful realm untouched by violence. For the artist, this type of painterly abstraction was the best means of communicating hidden aspects of the physical world and expressing subjective or psychological realities. Kandinsky, and indeed many early 20th century artists, believed that the artist's job was to reject the deceptions of ordinary, rational reality, and allow the truer subconscious reality to emerge. In this philosophy, they were influenced by modern psychology, especially the writings of Sigmund Freud.

The outbreak of World War I disrupted all aspects of life for Europeans. For Kandinsky, whose ideas and art were beginning to attract attention beyond Munich, having to return to Russia must have been especially frustrating. He had fled the traditionalist Russian art world in search of new ideas, but now Russia too was grappling with change. Kandinsky returned in 1914; then in 1917 the Russian Revolution overthrew the imperial government. For artists like Kandinsky, the Revolution seemed to offer an opportunity to do away with hidebound cultural traditions. The sense of freedom and openness to new ideas was intoxicating for the artists. Kandinsky participated in reforming Russian art education and museum organization. Though the artist also co-founded the Institute of Artistic Culture in Moscow, he soon found his individualistic philosophy rejected as selfish and bourgeois. Kandinsky returned to Germany in 1920.

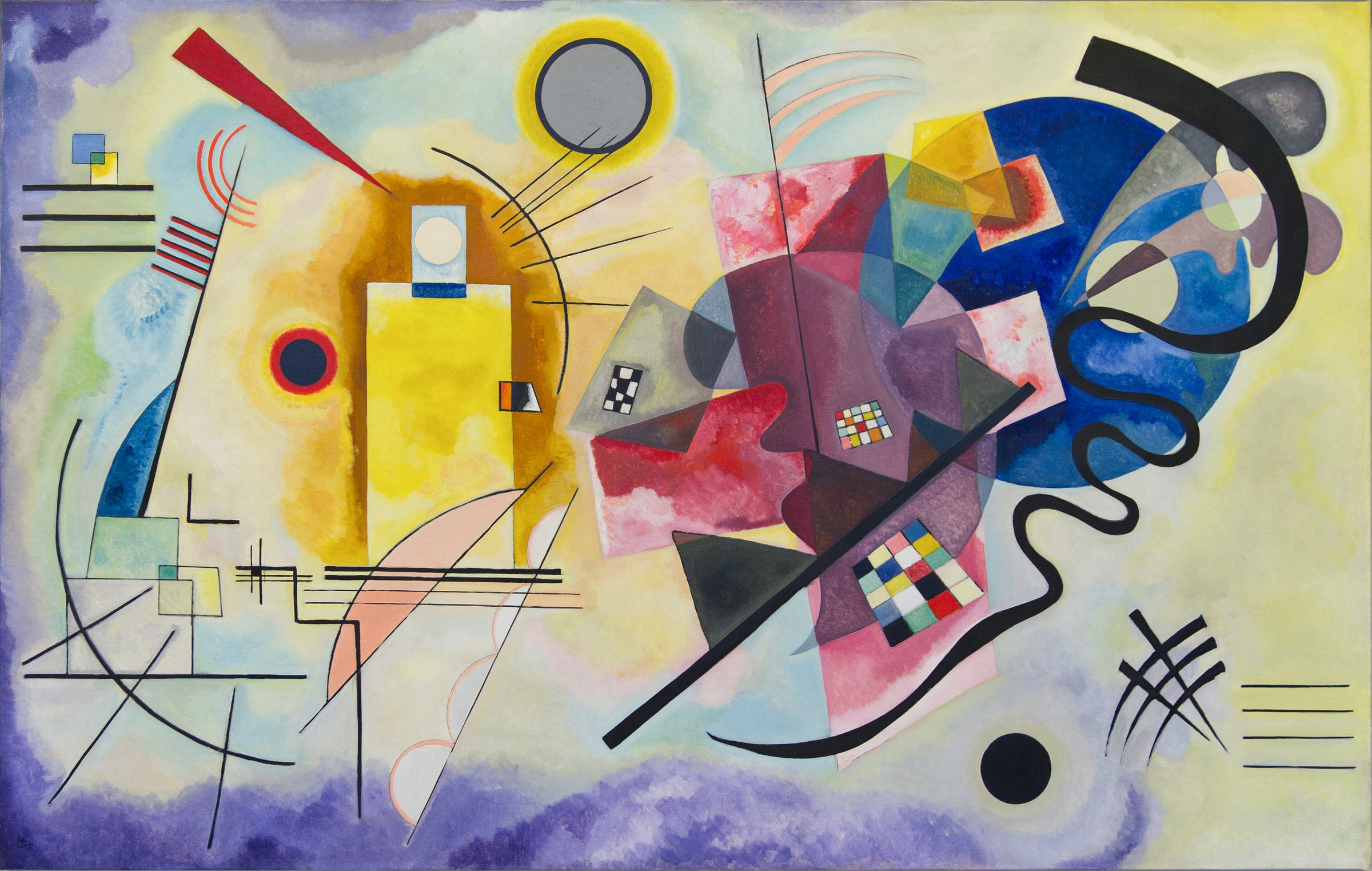

In 1922, Kandinsky was invited to join the faculty of the German government-funded art school, the Bauhaus. Established in 1919, the Bauhaus was an attempt to unify all the arts and to break down distinctions between fine arts, crafts, and industrial design. From 1922 to 1933, when the Bauhaus closed under pressure from the Nazis, Kandinsky taught the basic design course for beginners and advanced theory. During this period, the artist focused more on the Composition category, with carefully drawn lines and geometric shapes. Yellow-Red-Blue is one of the artist’s largest works from this period. The title refers to the three primary colors in the order that they progress across the canvas from left to right. For the viewer, understanding and interpreting a large and complex composition like this takes time. I’ve looked at it many times and often notice new details and connections in the composition. One approach is to begin by looking at and describing to yourself the colors and shapes you see. Kandinsky has used, in a more precise geometric form, some of his recurring motifs, colorful circles, an especially bold snake-like black line, sets of parallel lines, and the curve-and-eyelash motif. The composition is divided between the bright left and the darker right. The sharp geometry on the right also contrasts with the more irregular forms on the left. Consider the contrasts, repetitions and echoes. Did Kandinsky intend us to see a face in the yellow section of the painting or is this an instance of pareidolia (our mental habit of seeing faces in things like electrical outlets and tree rings)? Are the dark shapes another of Kandinsky’s scenes of conflict and how do these relate to the more peaceful yellow half? There is no right or wrong answer to these questions. Nor are these the only ideas that this painting might generate. Its combination of complexity and scale make this an important and memorable painting.

Several Circles of 1926 is one of a series of paintings depicting arrangements of colored circles. Kandinsky considered the circle the most peaceful shape and symbolic of the soul or spirit. In this painting, the circles seem to float like a galaxy in the darkness of space. The background is not a uniform color but consists of clouds of multiple dark tones surrounding the floating circles. Kandinsky saw art as a spiritual autobiography of the artist which allowed viewers to experience and enhance their own spirituality. Above all, the artist believed in conveying “inner necessity,” by which he meant an individual’s spiritual intensity and inner beauty. In 1909, Kandinsky had joined the early 20th century spiritual movement called Theosophy. The main tenet of Theosophy was universal brotherhood, an idea which appealed to many in Europe in the face in political and economic change. Theosophists also believed that after a coming calamity a new era of spiritual enlightenment would arise. The idea of this new era was especially attractive to Kandinsky as it connected to his own belief that art could create a spiritual link between the artist and the viewer for the betterment of both.

Color is a means of exercising direct influence upon the soul. Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand which plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul – Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, 1911

Of all an artist’s tools, color was the most important to Kandinsky. He believed that colors had direct links to spiritual or psychic reality (as opposed to visual reality). Kandinsky is thought by many to have experienced synesthesia, a perceptual phenomenon in which a person reacts with a sensory response that doesn’t correspond to the stimulus. For example, a synesthetic person may experience a specific taste when hearing a particular sound. Each synesthete experiences the phenomenon consistently throughout their life, but differently from others. Kandinsky associated specific sounds with colors (yellow was middle C as played by a trumpet) and thought that color combinations functioned in visual art as chords function in music. His choice of titles like improvisation and composition reflects his belief that “music is the ultimate teacher” for the non-objective artist.

With the closing of the Bauhaus in 1933 and the rising intolerance for avant garde artists in Nazi Germany, Kandinsky moved to Paris. In 1939 he received French citizenship and he remained in France until his death in 1944. The last two of the ten paintings titled Composition were completed in this period, Composition IX (Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou) in 1936 and Composition X in 1939. The first three Compositions survive only in black and white photographs as they fell victim to World War II. Composition I was destroyed by Allied bombers in 1944, but Compositions II and III were seized in a raid on the Bauhaus and exhibited by the Nazis in their propagandistic Degenerate Art Exhibition in 1937, after which the paintings were burned. The first seven Compositions, which were painted before World War I had apocalyptic themes. The final three, painted after WWI, are lighter and brighter, filled with energetic forms that convey a sense of hope. Composition X has a party atmosphere with floating ribbons of color, balloon-like irregular circles, and small squares of color reminiscent of confetti. The greenish-black background is cloud-like, similar to the one in Several Circles, but this painting lacks the cosmic calm of the earlier work. Familiar motifs from earlier paintings are represented more loosely in varying sizes, so that one sees those details in a whole new way.

Sky Blue seems very different from the other works I’ve included here, but it’s not such an outlier as that would imply. When he moved to Paris, Kandinsky began to incorporate small biomorphic shapes and objects into his compositions. These may remind the viewer of works by Paul Klee, Kandinsky’s colleague at the Bauhaus, or even more, of the Surrealists Joan Miro and Jean Arp. Some of the little critters that fall through the sky blue background (the red and green figure at top right and the orange-faced figure near the bottom, especially) are strongly reminiscent of characters that inhabit Miro’s paintings. From Arp, Kandinsky adopted biomorphic shapes like the central pink shape here and those in the darker sections of Yellow-Red-Blue. This final phase of Kandinsky’s career was a time of consolidation and synthesis as he played with the visual language and artistic theories that he had spent the previous forty years developing.

Video: Introduction to an exhibition of Kandinsky’s work held at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Oct. 8, 2021 to Sep. 5, 2022.

Wassily Kandinsky’s art and ideas were deeply influential in the art created in the years during and since his life. Through his publications Der Blaue Reiter Almanac, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, and Point and Line to Plane (1926), his teaching, and his many prints and paintings, the artist’s ideas spread throughout Europe and beyond and today he is considered one of the great masters of Modern art.

I really enjoy your investment in the viewer's experience of an image, including emotional and intellectual discomfort.

My favorite among the artworks shown, and new to me, is Yellow-Red-Blue. In reading your post and thinking about that painting, I suspect what I like so much is its musicality, in particular the sense of rhythm created by the interplay of color, shape, and line and their progression across the canvas. I had not really thought about or known much about how his art changed over time, and your post offers a mother lode of information about that in a concise, highly readable, space. I was also reminded, on reading the section about associating music with colors, of a trip to the Guggenheim long ago in which Impression III (Concert) was displayed together with audio of the Schoenberg piece that apparently inspired it. I don’t actually think that painting is one of Kandinsky’s best, but I was completely entranced by the art-music connection. Perhaps even more-so because of that, I often “relate” to his work as visual music. Thank you for the wonderful post!