I love winter, a season of waiting, of planning for warmer days to come, and of remembering happy times gone by. Reading and seeing pictures of the recent snows in the northeastern US called to mind a magical memory of a childhood winter. After one particularly heavy snowfall, an icy crust formed atop the snow. My friends and I discovered that if we moved carefully we could stay on top of that crust, right up until we stopped moving gingerly and cracked through into the deep snow. We’d compete to see who could go farthest before stumbling, and laugh as we all ended up tumbling through the snow. I’ve collected some works by artists who were inspired by winter. Enjoy these wintry works, whether you are surrounded by snowdrifts or thanking your lucky stars that you live in a warmer place.

Few artists express the inspiration they find in nature as directly as Andy Goldsworthy (Scottish, b. 1956). In most of his works, the artist creates temporary constructions from the natural materials present at his work site. He has woven sticks and reeds, sewn leaves together with blades of grass or pine needles, and broken pebbles with larger rocks, among a multitude of other interventions. The construction is photographed when complete and then left to decay as it is affected by the forces of nature. Winter has inspired some of Goldsworthy’s most awe-inspiring pieces. Working with icicles or blocks of frozen snow, the artist was often forced to build pieces in bitterly cold conditions and darkness, so that the finished sculpture could be photographed in bright sunlight but before temperatures rose enough to collapse the work.

When I work with winter, I work with the North. For me, north is an integral part of the land. … Its energy is made visible in snow and ice. — Andy Goldsworthy

In Touching North (1989), reproduced above, Goldsworthy traveled to the North Pole where his usual struggles with warming temperatures did not arise. Having learned traditional snow cutting and packing from an Inuit individual, the artist created a series of ring-shaped snow sculptures framing the North Pole. In keeping with Goldsworthy’s insistence on using only what is present at the site, there is no interior support holding the blocks in place; the rings are self-supporting. Circular shapes recur throughout the artist’s career, symbolizing the cycles in nature, as well as infinity and unity. From the center of Touching North, each ring frames the landscape to the south and also creates surfaces to interact with the sunlight. The interaction of his works with the movement of the sun is always an important concern for the artist. Goldsworthy’s goal is to capture the work in the best light, literally as well as figuratively, as he is trying to mark “the moment when the work is most alive.”

One of the great painters of snow is Claude Monet (French, 1840 – 1926). One of the leaders of the Impressionist movement, Monet was obsessed with capturing the transitory interactions of light and color in his landscape paintings. The Magpie, painted during the winter of 1868 to 1869, is the largest and is considered one of the best among the approximately 140 snowscapes Monet created. An innovation of the Impressionists was the use of colored shadows, abandoning the use of black to darken shaded areas and The Magpie is one of the earliest examples of Monet’s use of this technique. The title bird perches on a gate, drawing our eye and balancing the dark tree and rock wall in the right side of the composition. The darkest tones are confined to the middleground of the painting with the pale snow and sky filling both foreground and background. The sympathetic critic Felix Fénéon said at the time that "[The public] accustomed to the tarry sauces cooked up by the chefs of art schools and academies, was flabbergasted by this pale painting." The unconventional brightness of the painting is probably the reason that Monet’s painting was refused by the jury for The Salon of 1869. Repeated rejections from Salon juries eventually led Monet and his friends to give up on that traditional path to fame, establishing their own independent exhibition society to attract the attention of journalists and collectors.

In contrast to Monet’s depiction of sun on new-fallen snow, Settai Komura (Japanese, 1887 – 1940) captures the hush of snow falling on a lakeside home. In addition to paintings, Settai was a successful illustrator of books, newspapers, and magazines and set designer for both kabuki and shinpa (new or modern school) theaters. Settai used traditional Japanese materials, water-based paint on silk, and the thinly applied paint allows the threads of the woven silk to show through. Those threads echo the delicate lines of the architecture and both combine with the restricted color palette to intensify the sense of quiet in Settai’s work. The falling snow was created by spattering the surface with white paint. The spatters have irregular shapes and are unevenly distributed in contrast to the precision of the rest of the painting. Settai was trained in traditional Japanese painting and print-making techniques, but was also exposed to ideas from Western art of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The high point of view and lack of single point linear perspective reflect the Japanese tradition but the spare composition and innovative application of white paint suggest the influence of Western modern art.

Even Settai could not have imagined how few elements Pauline Ziegen (American, b. 1960 would require to communicate an image of winter. Mind of Winter (2023) suggests snow-laden clouds hovering over a red dirt plain with atmospheric color and a few rectangular planes. The artist applies multiple layers of marble dust-infused gesso, oil paint, and aluminum leaf to achieve the variations we see in the work. Now based in the American Southwest, the artist has studied at institutions across the country. Her experiences with the prairies of the Midwest and the open expanses of the Southwest have clearly influenced her depictions of space. In her works, Ziegen uses minimal materials to convey different moods and seasons, all influenced by her study of East Asian art and philosophy. In this painting, the sharply defined horizon contrasts with the misty color variations above and the offset rust colored planes below. The balancing of such opposites is one of her goals, as she seeks harmony between sky and earth, inner and outer, painting and landscape, all achieved with the simplest of forms.

I want to create haikus rather than sonnets. – Pauline Ziegen

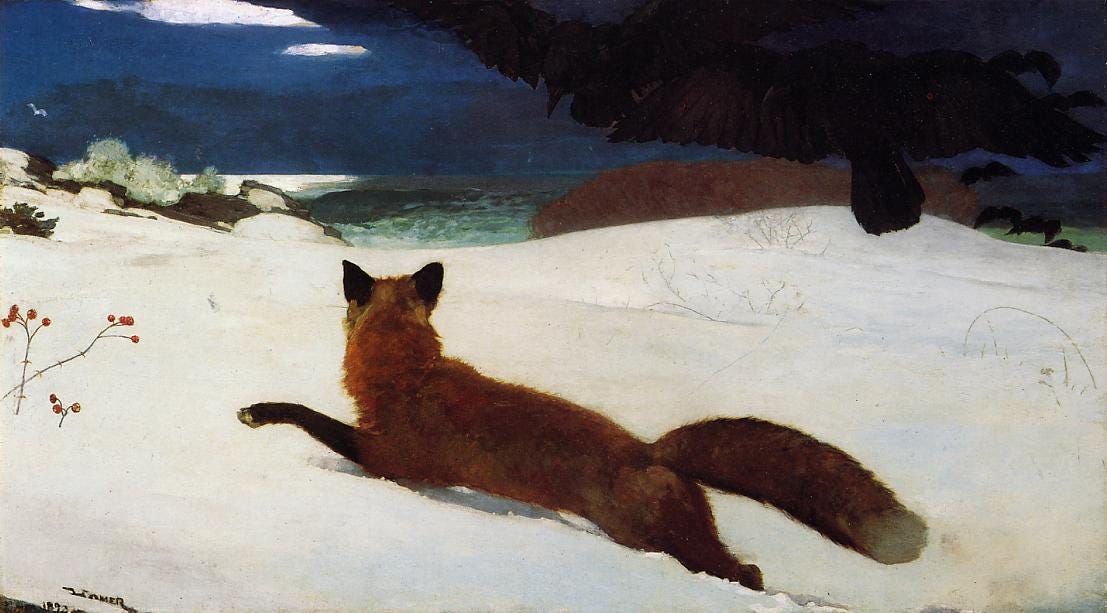

Winslow Homer (1836 – 1910) is one of the most important American painters in the history of art and Fox Hunt (1893) was the first of the artist’s paintings to enter a public collection, purchased in the year it was created. The largest work Homer had created up to that date, Fox Hunt depicts a moment of great tension, as a fox struggles through deep snow, trying to escape a threatening flock of crows. The painting represents a reversal of the usual hunter-prey relationship between a fox and birds and is one of a group of paintings the artist created during this period centering on survival against the forces of nature. Homer sets our point of view on the fox’s level, so we feel sympathy for it and feel ourselves threatened by the looming black birds. The artist’s use of red tones moves the viewer’s attention from left to right and from foreground to background. On the left, the sparse red berries direct our attention to the fox, while the mass of reddish bracken in the background echoes the fox’s fur, yet offers the animal no shelter from the marauding birds. An interesting touch is Homer’s signature, painted diagonally in the lower left corner. It looks almost like a stray twig or bit of rock, but closer study shows that the shapes of the letters imitate the fox’s pose with the tail of the R trailing down and to the right just like the fox’s tail. Viewers have seen this as an indication that Homer saw himself in the “dapper, small, inquisitive, shrewd” fox.

Homer was a Realist artist and he went to great lengths to achieve lifelike colors and poses for the animals in this painting. A fox pelt draped over a barrel allowed the artist to capture the color variations of the animal’s fur. Then two hunter friends supplied the artist with a frozen fox and two frozen crows which he tried to use to capture the correct forms for the animals. An untimely thaw ruined his efforts with the crows, so he and another friend spent three days attracting crows with corn so the artist could capture the birds’ hovering and swooping behaviors. To me, Homer’s painting serves as a prime example of how an artist can create a realistic scene yet manipulate visual form to endow that scene with intense emotion and deep symbolism.

Another artist to use a wintry scene for symbolic and emotional purposes is Oskar Kokoschka (Austrian, 1886 – 1980). The Bride of the Wind (1913-1914) is an allegorical painting, that is, the artist has represented a mythic tale that symbolizes an important relationship in his life. The visual form of Kokoschka’s work is typical of Expressionist style, especially the distortions in depicting the male figure (whose face is a self-portrait) and the visible brushwork and thick paint. Created while the artist was engaged in an intense affair with recently widowed Alma Mahler, Kokoschka’s intention was to paint a portrait of himself with his beloved. He originally titled the work Tristan and Isolde, after the Medieval romance in which the two protagonists fall madly in love due to a love potion. Such a title would have accurately reflected the obsessive passion felt by Kokoschka, but in consultation with his poet friend Georg Trakl, the artist changed to the present title, a reference to the tale of the bride of the North Wind. Tired of living alone in his cold, empty home, the North Wind travels to warmer lands and falls in love with a mortal woman. They marry and he carries her off to his frigid home. In the painting, the contrast of the mortal woman to the cold land and its master is expressed through color. All of the warm tones swirl about the woman asleep in her lover’s embrace. Bits of her warmth have seeped into her partner and even begin to spread into the landscape. This story has no happy ending, though, as the cold emptiness of the North gradually drain the bride of her warmth and vitality and the North Wind must let her go to save her life. Alma Malhler found Kokoschka’s obsessive passion disturbing and broke off their relationship in 1914. For the painter, this tragic event affected his mental health for some years after the event and he expressed his love for Alma in his poetry and other writings for the rest of his long life.

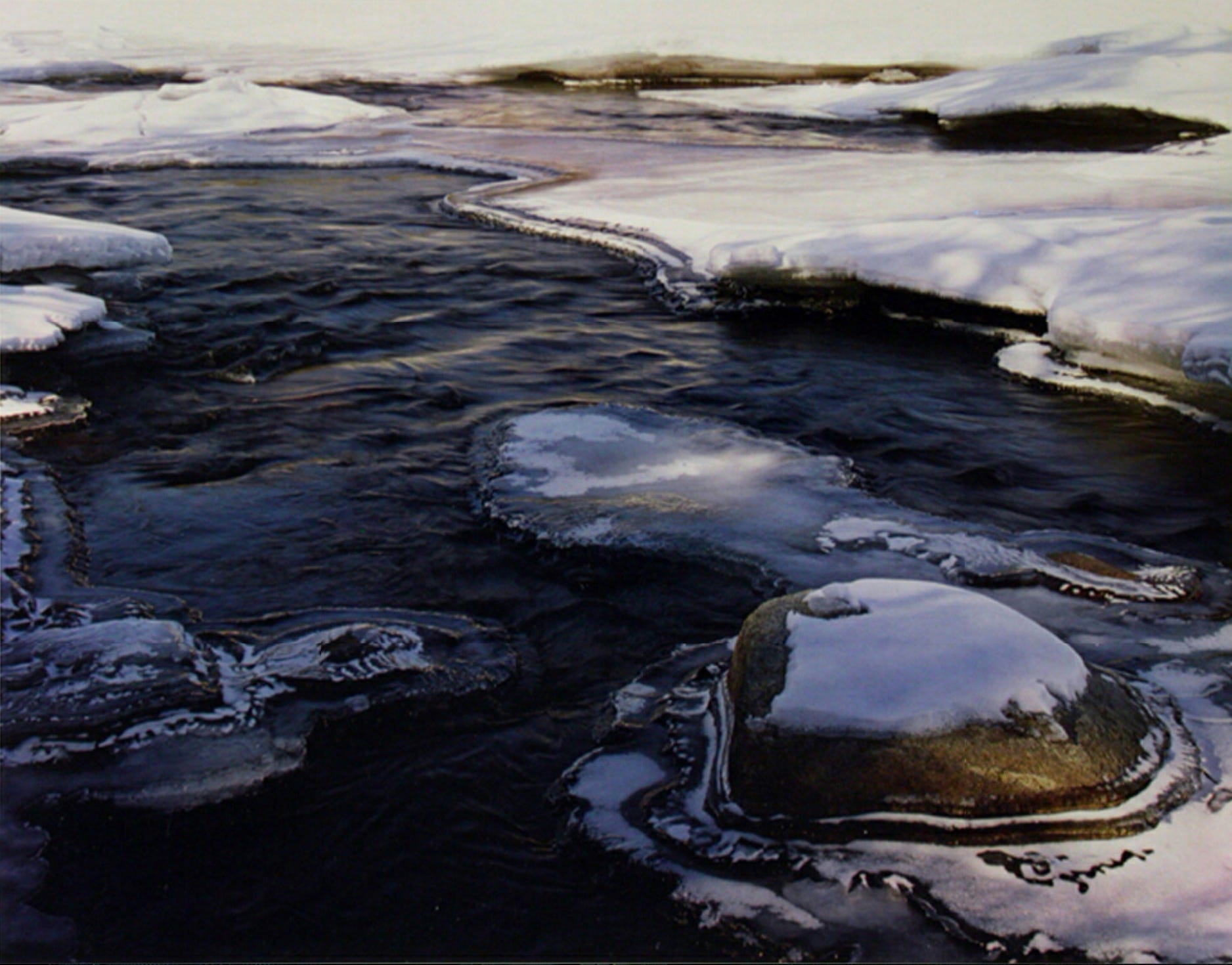

Photographer Eliot Porter (American, 1901 – 1990), a pioneer of color photography, captured the contrasts of dark moving water with patches of ice and snow in Winter River (1958). Without a horizon line, Porter leaves us without sense of scale. Is that a small rock in a shallow stream or a boulder in the midst of a great cataract? In common with other photographers of the early 20th century, Porter worked in black and white at first. In 1930, the photographer’s brother, painter Fairfield Porter (1907 – 1975), introduced him to the photographer and gallerist Albert Stieglitz (American, 1864 – 1946). Stieglitz encouraged Porter to work harder at his photography and eight years later presented Porter’s work in his An American Place gallery. As a result of the success of this show, Porter left his job as a medical researcher and devoted himself to photography full time. Always focused on nature photography, Porter turned to color photography in order to capture the plumage of birds. When color film didn’t provide the results he’d hoped for, he used his backgrounds in chemical engineering and research to improve his images. In 1943 the Museum of Modern Art exhibited his bird photographs, the institution’s first showing of color photography. From then on Porter traveled the world photographing ecologically and culturally significant sites. He worked closely with the Sierra Club which published many of his books, essentially establishing the concept of the coffee table book. In 1979, Porter’s photographs were exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art under the title Intimate Landscapes. As with his earlier exhibition, this was a landmark event, the Met’s first one-person show of color photographs. Winter River fits into Porter’s definition of an “intimate landscape,” a close-up view of natural elements with muted colors and varied textures.

Much is missed if we have eyes only for the bright colors. Nature should be viewed without distinction… She makes no choice herself; everything that happens has equal significance. — Eliot Porter

Like Claude Monet, American painter John Henry Twachtman (1853 – 1902) was a masterful painter of winter. The artist began his artistic studies in his hometown of Cincinnati, Ohio before traveling to Europe to study. This was a common path for ambitious American artists, because advanced artistic training was hard to find in 19th century America. Twachtman studied first in Munich, then visited Venice, and finally, during the 1880s, attended the Academie Julian, a prominent art school in Paris. There he learned the lessons of French Impressionism, using bright colors and painterly form to capture the individual artist’s personal experience of the subject. Upon his return to the United States, Twachtman acquired a farm in Connecticut where he used his Impressionist style to capture the landscape in all seasons, but most often in winter. End of Winter was created in this period and exemplifies Twachtman’s sensitivity to subtle color variations and his skill in using misty veils of color to unify the composition. Hints of the coming spring are found in the yellows and greens of the fields bordering the stream, though the pale lavender mist suggests that the weather remains cold. The poetic beauty that this artist found in winter has always inspired me to greater appreciation of the season. Twachtman died suddenly at age 49. Though he’d experienced limited commercial success, his works and his role as a teacher at the Art Students League in New York City ensured his legacy in spite of his shortened career.

Video: The Mamas and the Papas perform California Dreamin’ live in Monterey, CA in 1967.

Whether you’re dreaming of someplace warm and sunny or hoping for another good snowfall before the end of winter, I hope this group of works has shown you the beauty of the coldest season and perhaps inspired you to seek out the beautiful details in whatever nature has to offer you.

Reading this essay and seeing the images has made my month! As a photographer, I'm attracted to winter landscapes -- especially ice -- because of their move toward abstraction. I knew some of these artists but learned new things, like about Porter's work with color. The barescape also nourishes me as a writer. A book you might enjoy is Katherine May's _Wintering_ -- chapters on various ways to experience the season. Thanks so much for this essay I'll return to for sure! Love the variety of image and thought.

Wonderful post from you once again. A great selection, showing tremendous variety, and also new to me information even about paintings I thought I knew well, like Monet’s The Magpie. I am reminded of another winter painter, too, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, for example his Sunshine on Snow. I do find it remarkable how much an artist’s eye can bring to what we might otherwise think of as simply white.

I wonder, also, whether the painting “A Mind of Winter” may have taken its title from the Wallace Stevens poem, The Snowman:

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

Of the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

Thank you for this tremendous, evocative post.