Chance Encounters, Edition 26

100 Years of Surrealism, part 1

This is the first of a series examining Surrealism in honor of its hundredth anniversary. Exhibitions are being held around the world throughout this year and into 2025 in celebration. Available information about current and upcoming events is included at the end of the essay.

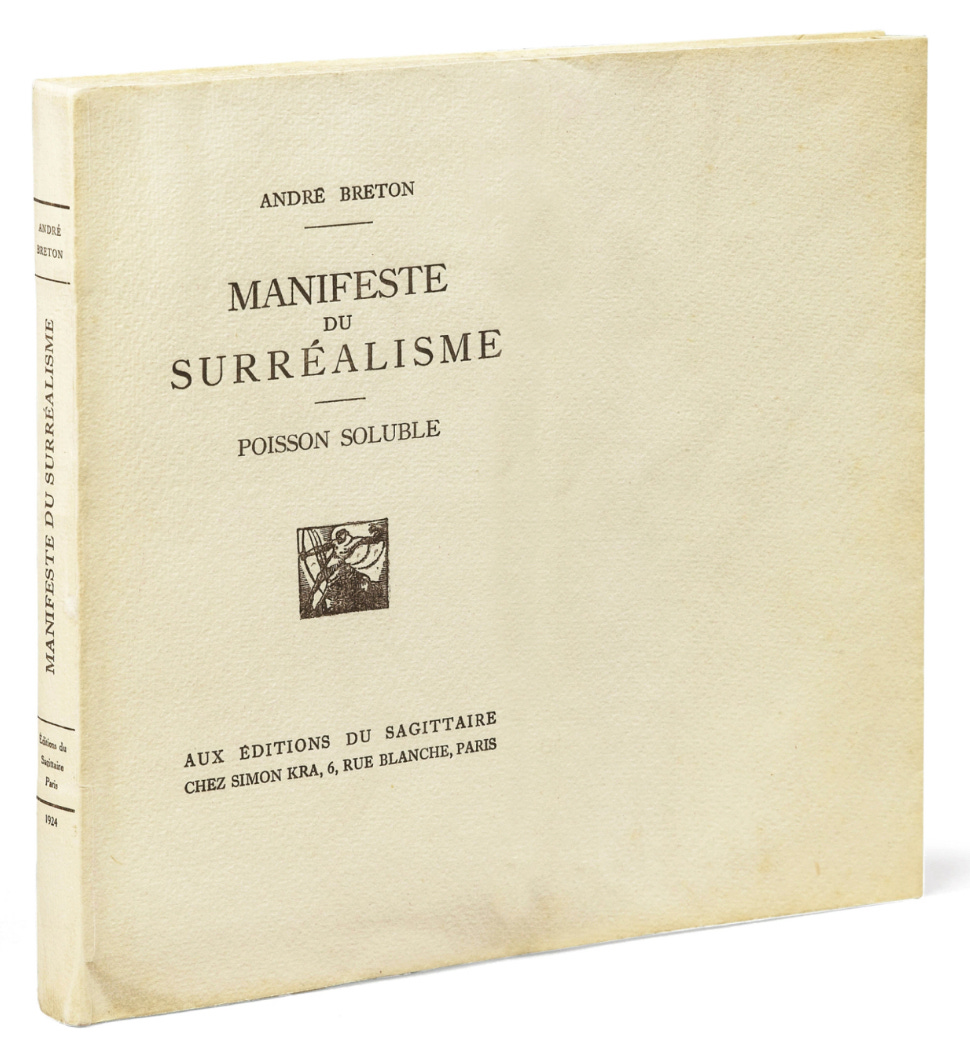

In 1924, the Surrealist movement was inaugurated with the publication of André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto (Manifeste du surréalisme). Link At least, the Manifesto is considered the official beginning of Surrealism, though the writers and artists who we today consider the founding Surrealists had already been using aspects of Surrealist philosophy for a few years. Texts like the Surrealist Manifesto, a literary statement of a group’s goals, were popular among late 19th and early 20th century art and political movements; they acted as a focal point for members of the movement, binding them together and making their ideas more concrete.

Breton (French, 1896-1966) said that the goal of the movement was to combine conscious reality and subconscious reality into a new absolute reality which he termed surréalite. This term is best understood as signifying a “superior reality” which is above or beyond ordinary reality. The Manifesto focused on literary uses of its philosophy, and though Breton seemed indifferent to the possibility of Surrealist visual art, he also said that the tenets of Surrealism could be applied to any aspect of life and should not be limited to the realm of the arts. These points can be discerned in Breton’s definition of Surrealism.

Pure psychic automatism, by which it is intended to express either verbally, in writing, or by any other means, the true functioning of thought. It is dictated by thought alone, in the absence of all control exerted by reason, and outside any aesthetic or moral preoccupations. – Andre Breton, Surrealist Manifesto, 1924

Though Breton’s publication is usually cited as the founding document of Surrealism, two weeks earlier German-French poet Yvan Goll (1891-1950) had published his own manifesto on October 1, 1924. Link (in French)

Goll’s ideas were similar to Breton’s with at least one key difference. Goll repudiated the importance of Freudian psychoanalysis and argued for basing Surrealism in reality that is taken to a higher level. Goll’s own works – he was a playwright and poet – featured a blend of fantasy, reality, and absurdity, suggesting how the writer thought this higher level was to be achieved. These dueling manifestos reflect a split within the Parisian avant garde which predated the 1924 publications. Both groups were dominated by writers and poets, though prominent visual artists Francis Picabia and Robert Delaunay were early members of Goll’s clique. Goll and Breton fought publicly over the right to use the name “Surrealism” and the disagreements eventually led to the victory of Breton as the gatekeeper and voice of Surrealism. The history of Surrealism in its heyday was a soap opera of frequent breakups, reconciliations, resignations, and excommunications that occurred over the years. Many of these were engineered by Breton based on his personal and political opinions; visual artists André Masson, Max Ernst, Matta, and Salvador Dalí were dropped from the group at various times, not because of changes in their artistic philosophy but because of changes in their relationships with Breton.

What is Surrealist art? Though it seems a very simple question, it can be difficult to answer. One of the underlying ideas of Surrealism was individuality, that is, each artist was free to express their own experience of dream imagery and imaginative free association. As a result there is no unifying visual form or appearance as there had been with earlier styles like Impressionism or Cubism. It is the psychological or conceptual basis of a work that identifies it as Surrealism. The artists are seeking to express something interior, an imaginative reality, which is characterized by disjunctions, or irrational juxtapositions, that pull the viewer away from their expectations and provoke a psychological awakening akin to what the artist experienced in creating the work.

Generally speaking, Surrealist art can be arranged along a continuum anchored by two poles, the abstract or organic and the dream or illusionistic. Some artists can be placed firmly at one pole or the other while most fall somewhere between the two. Battle of Fishes by André Masson, is characteristic of the abstract or organic pole of Surrealism. One of the important techniques of both literary and artistic Surrealism is automatism, the production of form through unplanned creation. In Battle of Fishes, the artist applied gesso (a sticky plaster) instinctively and randomly to the canvas and then spread sand across the surface, allowing it to adhere to the gesso before he brushed away the excess. Masson used this process in many of his paintings in the mid 1920s; he found that it created irrational but suggestive forms to which he would add drawn elements and paint applied directly from the tube. In this painting, the red paint indicates the bleeding wounds of the fish-like characters. Though fins and tails look like real fish, other details are more imaginative, in keeping with the Surrealist preference for such things. Masson, who suffered physical and mental wounds in World War I, believed that allowing chance to determine the appearance of his works would reveal the sadism inherent in all living creatures. This pole of Surrealism is called “abstract” for its dependence on schematic, simplified, or distorted forms from nature; it can also be termed “organic” for the use of biomorphic (life-shaped but imaginary) forms. Masson and Joan Miró were the most prominent early practitioners of organic Surrealism.

The opposite pole, dream or illusionistic Surrealism, is exemplified by the work of Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989), probably the best known Surrealist artist. For someone who was alive in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, as I was, Dalí was as famous for his public persona as he was for his painting. Appearing in public in a large cape, with his famously long mustache and a walking stick, Dalí kept his image in magazines and on television, supplanting Breton as The Surrealist in most people’s minds. Dalí Atomicus, Philippe Halsman’s famous portrait of the artist surrounded by floating objects, flying cats, and a spray of water, encapsulates the idea that Dalí’s life was as surreal as his art. The photographer was determined to capture the scene in a single shot, eventually requiring 6 hours and 26 takes. The only darkroom effect was to remove the supports for the “floating” objects. Halsman and Dalí had become friends after meeting in 1941, eventually collaborating on thousands of photographs with each proposing ideas and inventing new ways of creating playful Surrealist images with Dalí as the model.

The Persistence of Memory is one of Dalí’s best known paintings, in part because of its pictorial clarity and coherence. As a student in Madrid, Dalí spent hours at the Prado Museum intently studying the tools and tricks of illusionistic painting, looking especially at art of the 17th century when illusionism and even trompe l’oeil (trick-the-eye) painting was perfected. He used this study to develop what he referred to as his retrograde style, the illusionistic approach he used to depict the peculiar events and imagery for which he is known.

My whole ambition in the pictorial domain is to materialize images of concrete irrationality with the most imperialist fury of precision. – In order that the world of the imagination and of concrete irrationality may be as objectively evident, of the same consistency … as that of the exterior world of phenomenal reality. – Salvador Dalí, The Conquest of the Irrational, 1935

The apparent realness of the landscape and the objects, no matter how unbelievable melting watches are, contribute to the feeling that we have wandered into a dream. The landscape in this and many of Dalí’s works is based on a real place, the coast of Catalonia where the artist grew up. The foreground of the painting is where the impossibilities of the scene impress upon us that this must be a dream. The wavering forms of watches which we know to be made of solid materials may symbolize the unsettled quality of time in dreams. In the left corner, ants, Dalí’s favorite symbol of decay, swarm an orange watch case as if it can feed them. Just beyond, a fly seems to have landed, or perhaps become trapped, on the soft watch face. When asked if the painting had been inspired by Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, Dalí replied that it was prompted by a Surrealist’s perception of Camembert cheese melting in the sun. Strangest of all is the slug-like form draped across the center of the composition. It has been identified by some viewers as depicting the artist’s own profile, yet with its fading tail and apparently closed eyes it seems like a dead thing forgotten in the deserted landscape. As we explore the picture we realize that what seemed to mimic reality is full of deliberate deceit. It is a world like those in dreams, where things are taken out of our experience and transformed by our memories, hopes, and fears. The artist was always verbose, but usually obscure, when asked the meanings of his paintings and explaining a work by Dalí tends to reveal more about the explainer’s mind than it does Dalí’s.

Visual artist and poet Max Ernst (German-American-French, 1891-1976) ranged from one end of the Surrealist spectrum in his works. In Celebes, 1921, he created an image closer to illusionist / dream Surrealism while the work that opens this edition, The Wood, 1927, is more abstract. In The Wood, Ernst used the “grattage” technique in which thickly painted canvas was pressed over a textured surface (corrugated metal and rough wood in this case) and then scraped to transfer the texture. Ernst invented the grattage technique as a means of incorporating chance into his work. For the Surrealists, chance effects allowed artists to free themselves from rationality and to involve their imaginations through interpretation of the chance effects.

In contrast, Ernst created Celebes (also known as The Elephant Celebes) by mixing together disparate inspirations to create an image that is simultaneously real-looking and confusing. The shape of the large central object was derived from a photograph of a Sudanese corn crib which Ernst had seen in a book. The title was inspired by a German schoolboy’s sexual rhyme beginning “The elephant from Celebes has sticky, yellow bottom grease.” Celebes is the former name of Sulawesi, Indonesia; like the corn crib image, it is drawn from a non-Western culture. A further source of inspiration may have been Ernst’s experiences in World War One. These include the desolate landscape, the tree apparently made of metal tubes, and especially the multicolored metal structure atop the elephant which is reminiscent of a tank’s turret. The dark gray color and the hose-like form with its metallic collar add more mechanical qualities. The mask-like horned head suggests that the hose is a trunk while its emergence from a cutout opening in the body contradicts this by implying it is a tail. A pair of tusks seen protruding behind the body likewise suggests we are seeing the elephant from behind. Adding to the general oddity of the scene are the headless nude woman in the lower right corner who seems to beckon the elephant toward her and fish-shaped objects swimming in the sky of the upper left corner. For all the ways that Celebes can be connected to personal experiences and ideas of the artist, the resulting image is a picture puzzle for the viewer to unravel according to their own psychology. This is the intention of all Surrealist art – for the creator to use their imaginative surrealité to inspire the viewer’s own efforts in the same direction with the ultimate goal of achieving psychological freedom from confines of societal conventions.

In its beginnings, Surrealism was dominated by André Breton and the writers who had joined with him in this new endeavor. Within just a few years, as Man Ray’s photo (ca. 1929-1930) documents, visual artists had become integral members of the group. Though Breton’s early conception of Surrealism had not included visual art, practitioners like Dalí, Masson, and Ernst, and others, pictured here or not, demonstrated how well suited Surrealism and the visual arts were to one another. They were so well suited in fact that Surrealism has remained a mode of expression in the visual arts throughout the century since its invention.

Surrealism was indeed, from its beginnings, a multiplicity. … It’s a plurality. That’s why it’s so rich and so malleable: It can be used by different artists in different contexts. – Patricia Allmer, Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art history, University of Edinburgh

Current exhibitions celebrating the centennial of Surrealism:

Histoire de ne pas rire (History of not laughing). Surrealism in Belgium, BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts, Brussels, Belgium. Now open until June 16, 2024. Link

IMAGINE! 100 Years of International Surrealism, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium (in cooperation with the Centre Pompidou, Paris), Brussels, Belgium. Now open until July 21, 2024. Link

Upcoming exhibitions:

Surrealism and Us: Caribbean and African Diasporic Artists since 1940, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas, USA. March 10 – July 28, 2024. Link

100 Years of International Surrealism, Pompidou Centre, Paris, France. Opens September 4, 2024. Additional details to be announced.

If you know of other museum or gallery exhibitions of Surrealism or of individual Surrealist artists, please let us know in the comments.

Essays that I published last year focused on Surrealist artists Remedios Varo (Edition 14 Link) and Wolfgang Paalen (Edition 18 Link). In addition, one of the editions about Pablo Picasso (Edition 15 Link) addressed that artist’s interaction with the ideas of Surrealism.

Another terrific post, thank you so much! You do a wonderful job of showing the immense variety--the Masson was new to me, and I liked it particularly. Also, I do wish, when I visited Cardiff, I'd known of the Ernst and had been able to see it in person. The techniques used are really appealing.

I was fascinated to learn what the Halsman photography took to create--though I do confess to feeling bad for those cats, particularly the one that seems to be caught in the stream of water. So hard to imagine how he accomplished this, even given the number of takes.

Interesting to learn of the "power" relationships, who won, who lost, particularly the early Breton-Goll "competition." Reading now about Dali's dash, I was reminded somehow of Tom Wolfe (The Right Stuff, etc) and his white suit. That development of a persona, in addition to the talent, makes for quite a public personality. I'm delighted this is the first of a series, and am ooking forward to the next installments.

Dear Teacher,

Thank you for this great information. I still may not really like much of this art, but I certainly have a MUCH better understanding of it. Again, thank you for sharing your insight and knowledge with us.