Something in the fabric of the painting, of the poem, of the music hooks into some urgent need, that you don’t even know you have or want, and you stay with it, and you go on and on with it, and it opens and releases so much. – Pat Adams

In a career spanning seven decades, American abstractionist Pat Adams (b. 1928) has been interested in more than the technical and aesthetic problems she faces as an artist. Her wide-ranging interests, including perception, physics, and anthropology among many, have inspired her work as much as her use of innovative materials and techniques. Adams believes that our interests feed our imaginations and then our imaginations synthesize our knowledge and our feelings. This synthesis is an important aspect of the artist’s creative process and part of the content in all of her paintings.

Born in Stockton, California on the cusp of the Great Depression, Adams learned the importance of making something out of very little, but also the rewards of interacting with both nature and art. She treasures memories of growing up in the San Joaquin River delta and observing the interplay of plants and wind while on family fishing outings. Her grandmother supported her interest in art, giving her a full painting set when the artist was 12 years old. She also remembers fondly her youthful encounters with paintings at the Haggin Museum in Stockton to which she could ride her bike. Adams attended the University of California at Berkeley where she studied to be a painter but also began exploring fields that let her delve into the beginnings or “the primary, the elemental, the intrinsic” nature of things, concepts which recur when she speaks of her paintings.

Having graduated from Berkeley in 1949, Adams headed, as most young American artists of the mid-20th century did, to New York City. She arrived when the Abstract Expressionists dominated the city’s art world and some affinities can be found between her works and those by artists of that movement. Like many of the Abstract Expressionist artists, Adams uses painterly form, tries to incorporate chance into her works, and takes an instinctive, self-expressive approach to her art, all practices used by Abstract Expressionist painters. Adams’ works in the 1950s, like Norfolk – August 9, are small and usually made with gouache, an opaque form of watercolor, on paper. In these characteristics, the artist deviates far from the usually huge paintings of her New York School colleagues.

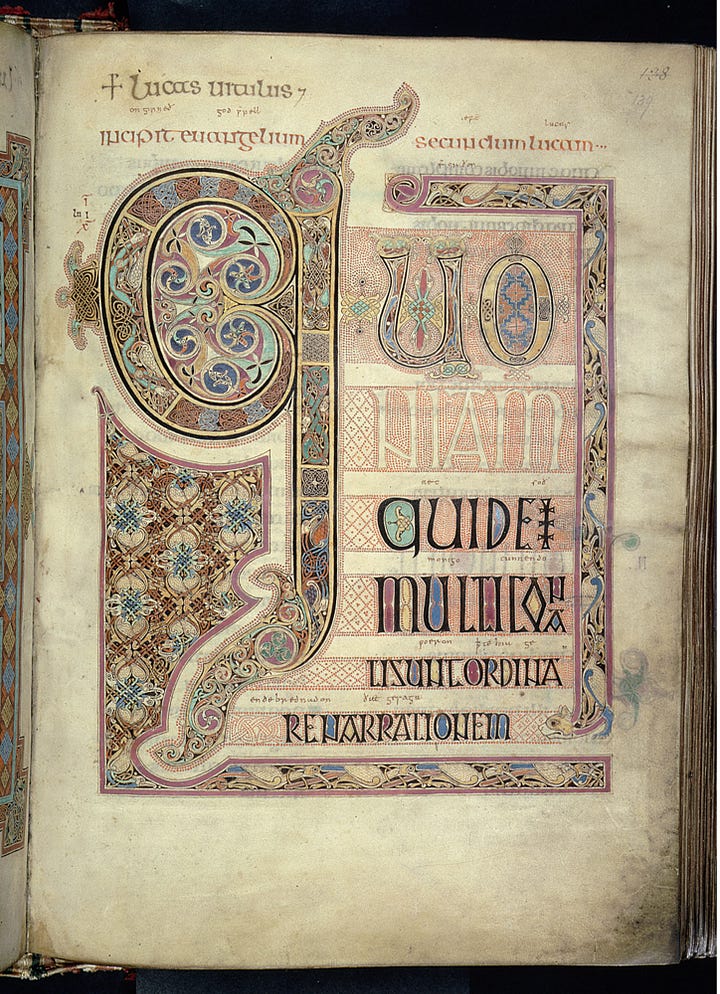

The profusion of mostly circular, multicolor forms in Norfolk – August 9 is partly inspired by the artist’s viewing of an Early Medieval manuscript, the Lindisfarne Gospels (715 – 720, British Library, London), during a visit to Europe in 1951 – 1952. Another inspiration from that European trip was the Medieval mosaic pavements found in Roman churches. Known as Cosmati or Cosmatesque mosaic, these pavements contain curving patterns and colorful tiles that match patterns found in this painting and others throughout Adams’ long career. (see above for these works) The tumbling colorful shapes also resemble the flowers of an overgrown garden while the circle in the deep orange field suggests the sun setting over a landscape. Adams’ abstract forms lend themselves to making multiple connections and the artist encourages such responses.

The viewer has to be caught, be attracted to something, and then sort of stay with it as the work reveals to [them] what it is.

In Walk, we see Adams exploring how her materials can create less structured and more suggestive forms. The roughly circular shapes are somewhat larger than in Norfolk – August 9 and seem to be sinking into or bubbling up from the expanse of swirling pale color. The leftmost shape, cut off by the edge of the painting, is framed by precisely drawn, undulating orange and yellow lines. In the first two decades of her career Adams was building a repertoire of motifs – undulating and swirling lines, circles, triangles, and squares, that populate her paintings for the rest of her long career. Though our attention is captured first by the wobbly circles, I also want to call attention to the blended color of the background. It suggests a foggy atmosphere or the surface of a river or pond. Such complex but subtle color backgrounds are a feature of many of Adams’ later paintings.

The question of size as a topic was never of interest to me. I was thinking about the materials I had at hand, how I would pack my work and get it back to the studio.

Walk, like most of Adams’ paintings from the 1950s and early 1960s, is small, and was made when the fashion among avant garde artists was for very large paintings. In this period she was traveling a lot, studying art in different places and visiting her home on the West Coast. Sticking with water-based, quick-drying paint and small sheets of paper allowed her to work steadily through her travels and carry her works with her as she went. However convenient this approach may have been, decades later, in 2021, in an interview with Jennifer Samet for Hyperallergic.com, Adams said that she “likes her small works most of all.” Indeed, the artist continued to create small paintings even as she began to work on a larger scale in the mid 1960s and beyond.

In 1964, Adams moved to Bennington, Vermont to take a teaching position at Bennington College. She retired from teaching in 1993, but still lives in Bennington. This change allowed her the space, time, and financial resources to begin working on larger scale canvases with a variety of new materials. Sliding Floor from 1965 is an oil painting with pencil on canvas, now in the collection of the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC. The color palette and the large expanse of solid, saturated green is reminiscent of the deep orange of Norfolk – August 9, but the later painting is four times larger than the earlier one. Another reminder of Adams’ earlier works is the undulating edges of the orange arch and red half circle that fill the bottom half of the painting. The interplay of multiple undulating lines gives this composition greater complexity than might appear at first glance. Something new in this painting is the mottled pattern of dark tones on the red ground. In the 1960s, the artist integrated a new paint application technique inspired by the monoprints of Maurice Prendergast (American, 1858-1924). Monoprinting consists of applying paint or ink to a smooth surface and then pressing the painted surface to paper or canvas. For Adams, the technique allowed her to create new color and paint effects as well as to incorporate an element of chance into her creative process. As time passed, the artist added many new materials and techniques to her layered surfaces, resulting in the dense textured surfaces seen in Such That (2008, above) and other late works (below).

Complex surface treatments appear in Adams’ small paintings as well as the larger ones. In Glistening Drowse (1970), the first impression is of a speckled pale blue expanse with a few more saturated turquoise patches. Our attention is then drawn to the triangle shape in the lower right which gives the impression of having been roughly stitched to the painting. The sharply defined black and yellow outline contrasts with the rest of the painting. Did you notice the faint undulating lines, purple to the left, and yellow in the right half of the composition? I didn’t when I first looked at this painting; I only saw them when I began to look more closely at the turquoise patches. There’s also a constellation of white dots in the upper right quadrant. This is what Adams is trying to achieve in her works, “entangling” the viewer’s attention so that the painting’s qualities are “loosed into the reaches of the mind.”

Free More (1989) is a small painting with a monumental presence. It also demonstrates the literal density of surface that Adams created in works from the 1980s. Some works from the 1970s saw the introduction of sand and mica for texture and sparkle, but in the 80s, the artist began to apply multiple types of paint (acrylic and encaustic in this case) and added eggshell and beads to some works. Even areas which appear smooth from a distance are revealed to have complex patterns of texture when viewed more closely (see details below). This painting is an excellent example of Adams’ repertoire of motifs, too. Filled and open circles, precisely defined lines, triangles and wedges, and rectangles filled with pattern are all elements which make appearances of works from the 1970s on. The white and red dotted lines hark back to the inspiration of the Lindisfarne Gospels where patterns of red dots are featured in many images. These dots and the sharp lines superimposed on the overlapping circular forms suggest a scientific diagram, though these details were as instinctively chosen as all of the elements in Adams’ works.

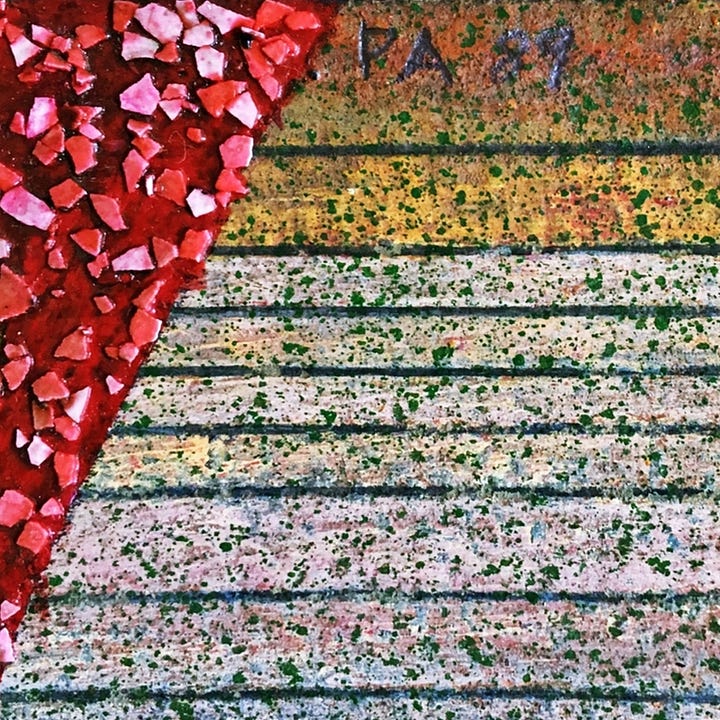

In these two details from the left half of Free More, the dense texture of the red shape is revealed to have been created with shattered eggshells. The striped section contrasts the precisely drawn lines with the speckling of paint over the whole section. The detail showing the gray circle also shows some of the textures of the larger dark circles. To me these suggest weathered stone and they are clearly the result of previously applied layers of texture. Adams has said that every work begins with an impulse, a couple of marks or a particular color. At that point she may do more with the painting, or set it aside to be considered at a later time. Of course the larger works require more advance planning but the progress of every painting is similar. Adams believes that an artist needs patience, a willingness to wait until what the painting wants or needs becomes apparent. For this artist, things emerge slowly and she rarely has an idea when the work will be finished.

Even in a dark and nearly monochromatic work like Unforgetting (1994), Adams demonstrates the layering of materials, shapes, and colors that she has mastered over her career. Where the preceding work was small but created a monumental effect with its density of textures and layered forms, this painting is literally monumental at six feet wide. The large circular form is crowded by the small, orange-flecked green square in the lower left and the larger, dark striped square in the upper right. The echoing of flecks and streaks of greens, golds, and oranges across the canvas brighten the mostly gloomy palette of this work, while the textured areas of the big circle suggest we are looking at continents on a planetary surface. The title Unforgetting doesn’t help much in deciphering what this combination of shapes, textures, and colors might mean. Of her titles, Adams has said

Usually, the title is something that has some remote connection to the painting, but it’s mainly for the beholder to have some place to put their feet on as they try to enter a strange situation.

Now in her mid 90s, Adams has limited her art-making to creating small collages like Late Scape. Asked when she will exhibit them, the artist replied that she makes them for herself, out of necessity. Art-making is her way of dealing with the world. This example was donated to a fund-raising auction benefitting the National Academy of Design of which the artist is a member. Adams begins her collages with a scrap of paper, a photograph, some piece of her world. These physical scraps are analogous to the bits and pieces of images, materials, and ideas that she brought together in her paintings. The artist’s term for the scraps of knowledge and objects that she has picked up throughout her life is quiddities, a term from Medieval philosophy that refers to the inherent nature or essence of a thing. They are things that may not even have a name, bits and pieces taken out of context. As they collect, they take on forms and relationships that she wants to use in her works. She spends long periods of time collecting the materials for her collages, just as she spent long periods of time with her paintings, waiting to find which those bits which speak to others. Then she spreads them on paper to see if they will coalesce into a composition that has the equilibrium she seeks.

At nearly 11 feet wide, Interstitial is the largest of the paintings I chose for this edition. Painted in 1987, it contains many of the motifs, materials, and techniques that Adams had developed in the preceding decades. This painting makes extensive use of wiry colorful lines overlaid on a universe of solid, open, and semi-filled circular forms. The more I look at Adams’ paintings, the more I’ve come to appreciate the “visual transaction” that she is seeking to create with the viewer.

What are the steps of perception that need to take place so that the viewer gets to the point where they can reflect upon what has been released in their imagination?

This is Adams considering both sides of that visual transaction. What she does in the studio is create a work that has such density of color, texture, shape, and often materials, that the viewer who stops and takes time to absorb it all will be rewarded, not just while looking at the painting, but afterwards as the work lives on in memory.

Pat Adams has been appreciated by many of the leading New York art critics during her career. In 1956, art historian Dore Ashton admired what she called Adams’ “delicate, poetic touch.” In 2005, Lance Esplund wrote in The New York Sun that she was “one of the most important abstract painters.” More recently, New York Times art critic Roberta Smith admired Adams’ “visual and philosophical richness” and wondered why none of the artist’s works were to be found in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art. Though few of us may have known her work before now, many will now agree with these assessments of Pat Adams’ paintings.

An exhibition of Pat Adams’ works from the 1950s and 1960s is currently on display at Alexandre Gallery, 25 East 73rd Street, New York, NY, continuing until April 20, 2024. (Link)

Another wonderful artist brand new to me. Such variety, and so much to see in this paintings, all the more so because of your able guidance. I particularly enjoyed your walk-through of Glistening Drowse. Best of all, I am now alerted, thanks to you, of the exhibit in NYC right now. I very much hope to be able to get to it, and will “report back” when I have.

Love the Pat Adam’s paintings. New artist to me love that style