In April of 1874, a group of artists opened the first independent art exhibition in Paris, now known as the First Impressionist Exhibition (though the term Impressionist had not yet been invented). Because Impressionism is extremely popular today, it is difficult to understand how radical and controversial this movement was in its early years. In this edition, I will share with you the early developments of the Impressionist movement and some works which appeared in that unprecedented exhibition.

The artists who founded Impressionism became friends in the early 1860s. Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley met as students in the same school and they encountered Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro, and Paul Cézanne during discussions of art at their favorite café. At the time Manet was a leader of the Realist movement and the younger artists admired him greatly. (For more on Manet, see Chance Encounters, Edition 5.) Through his contacts with the younger artists, Manet eventually shifted his own style toward Impressionism, though he never participated in their exhibitions.

Impressionism evolved from Realism, taking the earlier style’s use of painterly form (visible brushstrokes) and interest in contemporary life. Where the younger artists diverged from their predecessors was in color, which was lighter and brighter, and in preferring to work outdoors (en plein air). Claude Monet (French, 1840 – 1926) has long been viewed as a leader of the Impressionist movement and his work Poppies (also known as Poppies at Argenteuil), 1872, demonstrates most of the characteristics of the style. One of Monet’s nine entries in the First Impressionist Exhibition, the painting was created out of doors and captures the elements of the landscape with visible brushstrokes. The figures are depicted as patches of color, no different from the grasses, trees and clouds. The title flowers are patches of red and orange, more vivid near the picture plane and growing paler as the artist depicted the middle ground. The Impressionists believed that each artist should depict their subject as the individual saw it under particular conditions of atmosphere and light. Monet and his colleagues painted a subjective interpretation of reality and this was one of the most controversial aspects of the new style.

In 19th France, how artists should paint or sculpt was determined by the Académie des Beaux Arts (Fine Arts Academy). Any artist who wished to receive commissions and to sell their work would strive to study with approved masters and to have their works accepted for display at the official exhibition known as The Salon. To give an idea of what was most admired by orthodox taste in the 1860s and 1870s when Impressionism was developing, I’ve selected Nymphs and Satyrs, painted by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (French, 1825-1905). Bouguereau’s mythological subjects and allegorical themes in which concepts like innocence and charity were personified by idealized young women were extremely successful. His style follows the teachings of the Academy’s masters: ivory-skinned idealized bodies in graceful poses, realistic-looking natural settings, precisely painted details, and absolutely smooth surfaces with no obvious brushstokes. Comparing Monet’s approach to painting grasses and trees with Bouguereau’s, we notice Monet’s colors are brighter with blurring between one color are and the next. Bouguereau’s every leaf is carefully outlined, with its veins and shades of green precisely described. The leaves are as idealized as the female bodies. Throughout the painting, colors are neutralized by the use of grey tones to create shadows. This style, now known as Academic painting, is objective in its interpretation of appearance.

Berthe Morisot (French, 1841 – 1895) was one of several women who were important members of the Impressionist movement. She was a member of the organizing committee for the First Impressionist Exhibition and participated in seven of the eight Impressionist group shows. Her painting Reading demonstrates the Impressionist painterly style and bright color but also provides the opportunity to contrast the preferred subjects of the Impressionists and The Academy. Like Monet, Morisot has chosen a moment of leisurely activity in nature which she painted en plein air. Morisot’s young woman is the focus of her composition while Monet was clearly more interested in the landscape in his. Landscape painting had been growing in popularity in European art since it first developed in the 17th century. However, landscape painting was considered a lesser theme by the French Academy, even in the mid-19th century. Morisot’s subject is considered a genre subject, a scene of ordinary daily life without any underlying moral, religious or political meaning. Like landscape, genre scenes began to grow in popularity from the 17th century but such themes were valued even less than landscape. We may recognize that the purpose of Bouguereau’s painting is simply the depiction of beautiful nude women, but by choosing mythological characters, he aligned himself with the standards of The Academy.

One other point of difference between most Academic paintings, including this one, and early Impressionist paintings is size. Morisot’s painting is only 18.1 by 28.4 inches (46 x 71.9 cm); Bouguereau’s is 8.5 FEET tall and almost six feet wide (260 x 180 cm). Big paintings insisted on their importance when exhibited at The Salon where paintings were hung frame to frame, from about waist high right up to the high ceilings of former palaces. Smaller paintings which often depicted the less valued subjects of landscape, genre, and still life, were less likely to be noticed. Monet, Morisot, and their colleagues never had the opportunity to know if their paintings would be noticed at The Salon, though, because their works were never accepted by the jury which determined who was worthy of inclusion.

Another member of the organizing committee for the First Impressionist Exhibition was Camille Pissarro (Danish-French, 1830 – 1903). Within the Impressionist group, Pissarro was one of the most committed to the idea of supporting one another through their group exhibitions; he was the only artist to participate in all eight of them. Orchard in Bloom, Louveciennes, one of Pissarro’s six entries in the first exhibition, demonstrates the Impressionists’ interest in landscape, use of painterly form, and rejection of black and grey in their palettes. A characteristic feature of Pissarro’s works is the inclusion of workers in his paintings. They aren’t emphasized or idealized but if you examine this artist’s landscapes, you will find farmers, gardeners, craftsmen, or laundresses at work among the houses, trees, and streams.

The First Impressionist Exhibition was more than a year in the making. The group of organizers first created a joint stock company called the Society of Painters, Sculptors, Engravers, and Lithographers. Artists paid a subscription fee of 5 francs per month to participate. The group struggled to agree on a charter, taking most of a year to settle on their shared values. One disagreement was over the participation of “outsiders” – artists who didn’t paint in the Impressionist style. Edgar Degas (French, 1834 – 1917) successfully advocated for including a broader spectrum of styles, both to increase financial participation and to prevent the appearance that the exhibition was just disgruntled artists who couldn’t get into The Salon. The next argument was how to hang the paintings; at the Salon the process was often marked by favoritism. In the end they decided to group the paintings by size and draw lots. Unfortunately, the exhibition was largely unsuccessful from a financial standpoint, only a few works were sold and the Society had to be disbanded by the year’s end, due to its debts.

Though art dealers had exhibited outside the confines of The Academy, “The Exhibition of the Society of Painters, Sculptors, etc.” was the first self-promoted independent art exhibition in Paris. The exhibition took place over one month in a large space providing plenty of light for daytime viewing. Two hundred people came the first day and in the end a total of 3500 visited. Another innovation was evening hours made possible by gaslight, advertised as making the exhibition accessible to those who had to work through daylight hours. Response to the exhibition was largely negative. One critic thought perhaps it was all a joke, a comedian “dipping his brushes into paint, smearing it onto yards of canvas, and signing it with different names.” Another reviewer wrote

We have seen an exhibition by these impressionalists (sic) on the Boulevard des Capucines, at Nadar’s. M. Monet – a more uncompromising Manet – Pissarro, Mlle Morisot, etc, appear to have declared war on beauty.

A columnist for La Patrie encouraged readers to visit for laughs, though they also referred to the artists as “lunatics,” so one understands why the popular cartoonist known as Cham captioned his drawing (above, left) "Impressionist painting: a revolution in painting that is starting to spread alarm." I notice that he doesn’t say whether the revolution is a good or a bad thing. The most famous criticism was from Louis Leroy, whose column entitled “The Exhibition of the Impressionists” included

Impression! Of course. There must be an impression somewhere in it. What freedom … what flexibility of style! Wallpaper in its early stages is much more finished than that.

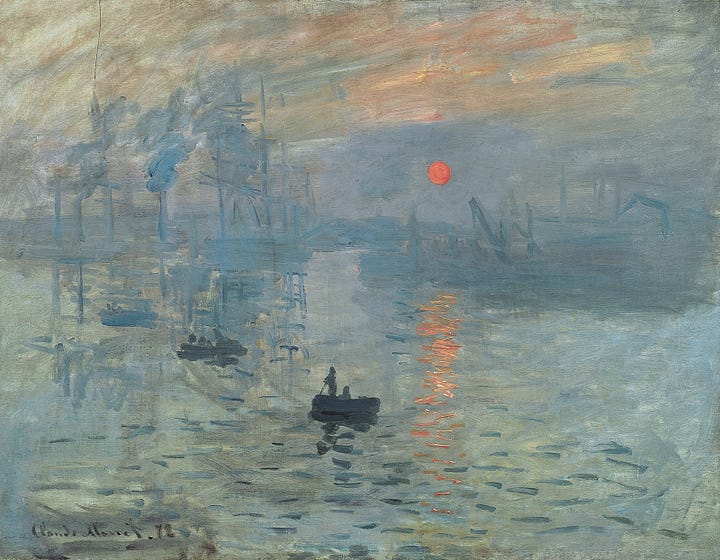

The focus on the word “impression” derives from a painting by Claude Monet, Impression – Sunrise, 1872. (above, right) Critics dubbed the group “Impressionists” from 1874 on, though the artists didn’t adopt the name until 1877.

Edgar Degas was another member of the organizing committee for the First Impressionist Exhibition and submitted 10 works to the show of which one was this small painting called The Dancing Class, ca. 1870. Though other artists eventually adopted the name Impressionist for their style, Degas never did. He insisted on the term Independent and was, from the very beginning, dismissive of the idea of plein air painting. Degas was not interested in capturing spontaneity and though he painted some wonderful horse racing scenes based on plein air sketches (for more on Degas, see Chance Encounters, Edition 5), he viewed himself as a figure painter. Today, Degas is famous for his scenes of ballet dancers, on stage, in the classroom, and backstage; The Dancing Class was his first use of the subject. The artist didn’t have access to the Paris Opéra at this stage of his career, so his models came to the studio where he created numerous studies which he later used to create paintings like this one. The work has many of the characteristics Degas is known for – a strongly asymmetrical composition, the use of mirrors, windows, and doors to expand and complicate the space, and figures in varied and sometimes awkward positions.

Paul Cézanne (French, 1839 – 1907) is known today as a Post-Impressionist artist but at this point in his career he was still learning the techniques and philosophy of Impressionism. The Hanged Man’s House, Auvers-sur-Oise was also included in that first exhibition and shows many of the qualities that we expect to see in an Impressionist painting. The brushstrokes are visible and the color matches the apparent late autumn season. The view we see hasn’t been chosen for its pictorial beauty; it looks like an awkward corner of a country town. That awkwardness is enhanced by deliberate violations of traditional linear perspective, a practice that the artist utilized throughout his career. Cézanne recognized that as we look across a scene, our perception of various objects would shift as our eyes moved. Thus our perception of the road going down toward the painting’s center is distorted by our attention shifting up toward the house. As time passed, Cézanne diverged from the Impressionist style, resulting in a completely individual style that nevertheless owed its interest in the interaction of light and color to the artist’s early years of working with Camille Pissarro and other Impressionists.

Alfred Sisley (British, 1839-1899) was born in France to British parents and lived most of his life in France. In spite of earning the most money from sales at the First Impressionist Exhibition, Sisley is probably the least known of the early Impressionists. While his colleagues saw steady success in the 1880s and 1890s, Sisley did not and died in poverty in 1899. The Route from Saint-Germain to Marly from the First Impressionist Exhibition is typical of Sisley’s works, a quiet scene with a beautiful blue sky and a silvery morning light. Blocklike brushstrokes capture the appearance of the cobblestones while smoother patches of color define the buildings. Art historian Robert Rosenblum has described Sisley as an almost generic Impressionist but in his best works, and I think this is one, the artist perfectly captures a sense of a place and time of day in his paintings.

The Impressionists were encouraged in their desire to work outdoors by an important innovation of the mid19th century. That was the invention of paint in tubes. In earlier Times, artists had to grind their pigments and mix them into oil for themselves. If they wished to work outdoors, they would put the paint into in a dried animal bladder. Purchasing premixed paint in a foil tube made the life of a plein air painter much easier. Impressionist artists like Sisley were also encouraged to be more sensitive to color variations in nature by the presence in their paint boxes of new synthetic paints that expanded the colors available without mixing – mauve and other purple tones, cadmium yellow, cobalt and cerulean blue, and synthetic ultramarine, a shade of blue which had previously been exceedingly expensive. It was now usually possible for a painter to notice a color and produce it from a tube of paint without having to struggle over mixing a precise matching shade.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, 1841 – 1919) is among the best known Impressionist artists and was active in developing the early philosophy of Impressionism and in organizing the First Impressionist Exhibition. La Loge shows a fashionable woman and her escort in a theater box; she holds her opera glasses in a gloved hand while he uses his to look up, perhaps at some other fashionable member of the audience. Though the Impressionists preferred not to use black paint in their works, it was sometimes necessary given the prevalence of black fabrics in the fashions of the day. Unlike most of the other works I’ve included here, Renoir is depicting an indoor subject, but that hasn’t kept him from exploring different light effects throughout the work. The woman in the foreground is brightly lit, her necklace and diamond earrings reflecting multiple points of light. The man behind her is out of the direct light and so is painted with blurred features and in more muted tones with patches of blue shadow on his white shirt. Looked at from a distance, the details of the painting seem quite precise, but closer examination shows that everything is made up of visible brushstrokes. It is this painterliness that made conservative viewers see these works as unfinished. Those viewers did not understand the radical philosophy that drove Renoir and his colleagues, that art should be the result of the individual’s perceptions of their subject. What conservatives saw was artist’s breaking artistic rules and what they feared was that these artists might also advocate breaking societal rules as well. In fact, the majority of the Impressionist artists shared the middle class or upper middle class values of their critics. Their revolutionary views were limited to their art.

In the 150 years since the First Impressionist Exhibition, the art world has experienced one avant garde after another, each as controversial as its predecessor. We have come to see the bright colors and ordinary themes of Impressionism as soothing and pleasurable. I’ve tried to show why the first viewers to experience this art were so startled, offended, and even alarmed.

Multiple exhibitions are open or scheduled in celebration of the anniversary of the first Impressionist show including the following:

• Impressionism and Its Overlooked Women: Odrupgaard, Charlottenburg, Denmark, until May 20

• Paris 1874: Inventing Impressionism, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France, until July 14

• The Impressionist Revolution (Monet to Matisse), Dallas Museum of Art, Texas until Nov 3

• Women of Impressionism: National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin June 27-October 6

• Paris 1874: Inventing Impressionism, National Gallery, Washington DC September 8-January 19, 2025

Thanks for reading. I’ll be back next week with a new topic.

Wonderful commentary, as always—and I always learn something new. I hadn’t realized, for one, that impressionists avoided using black or gray. I will now always be on the lookout for that. I appreciated your comments on and choice of Sisley painting. I have seen only a few Sisley’s, but even from that, I don’t really understand why he is and was so downgraded. His paintings, or at least the few I’ve seen, aren’t flamboyant in any way, but as in this one, they beautifully capture peaceable moments. Also of interest, in that vein, is the downgrading of certain subject matters, landscape, genre even lower, and still life. Even though I’ve read explanations, I don’t see why there must be a ranking or competition in type of subject matter, as it seems to me that any subject matter can yield great and lasting art.