Chance Encounters, Edition 32

Georgia O'Keeffe In the Middle of a Roaring City: New York Paintings

“One can’t paint New York as it is, but rather as it is felt.” –Georgia O’Keeffe

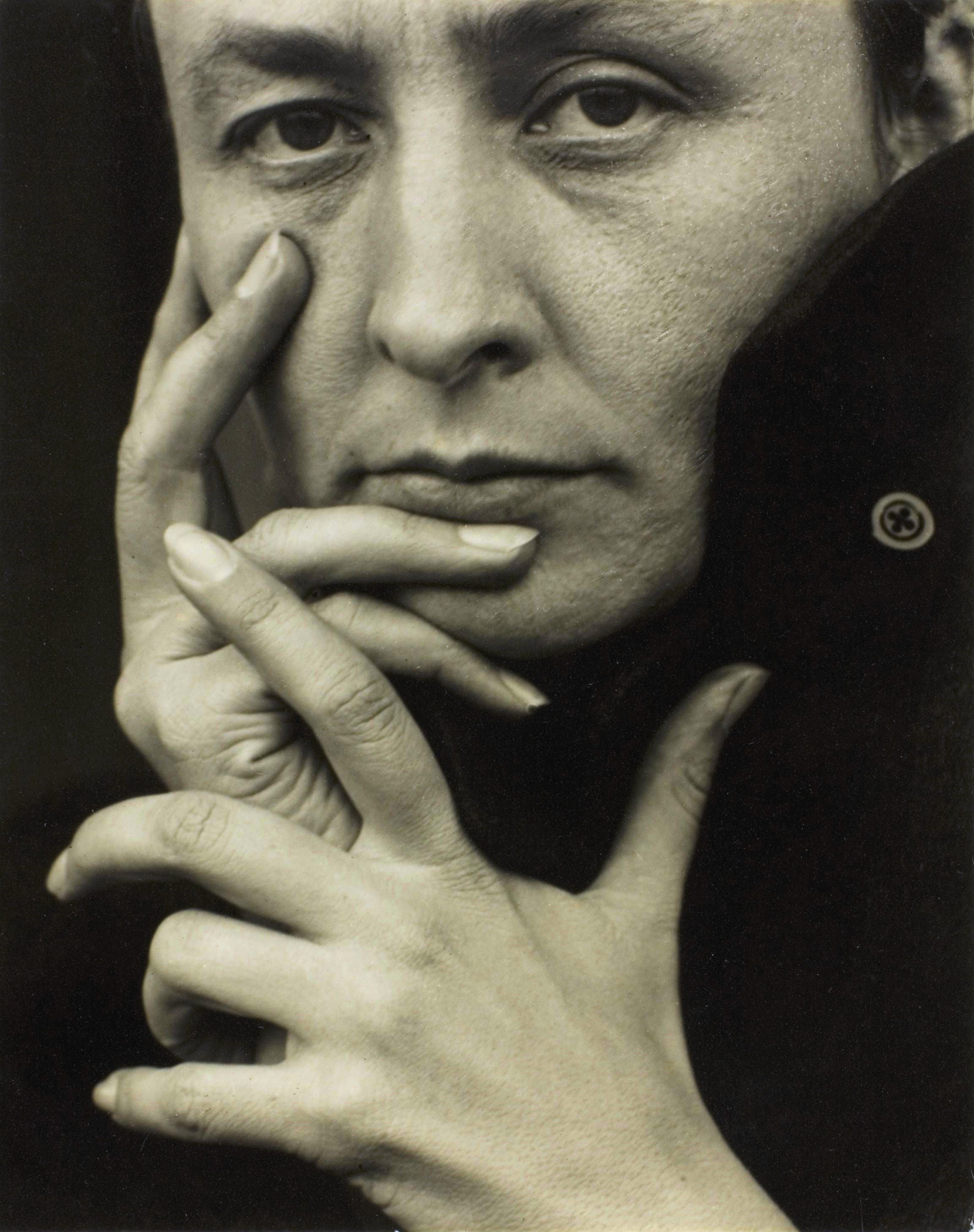

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) was a trailblazer in American art. Best known for her paintings of close-up flowers and desert landscapes, O’Keeffe created a series of about two dozen New York City scenes during the 1920s when she was living in the city and establishing her career. O’Keeffe had moved to New York City in 1918, joining Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) and his circle, which placed the artist among the avant-garde in the United States. As a result, the years between her arrival in New York and 1930 were some of the most productive of her career, both in the number of works created and the variety of subjects undertaken, including the earliest large flowers and the skyscraper paintings. Like many artists working in New York in the early twentieth century, O’Keeffe tried to capture the energy of the Jazz Age city in her works. Though not her best known work, the New York City series demonstrates O’Keeffe’s determination to “fill space in a beautiful way.”

Born in Wisconsin in 1887, O’Keeffe studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (1905 - 1906) and at the Art Students League in New York City (1907 - 1908). From 1908 to 1910, she worked as a commercial artist in Chicago and then taught art in Virginia, South Carolina, and Texas from 1911 to 1918.

While a student at the Art Students League, O’Keeffe first visited Alfred Stieglitz’s now iconic Gallery 291. Already a noted photographer, Stieglitz (1864-1946) opened 291 in 1905, becoming a major force in advancing the careers of many important American artists, including O’Keeffe. In 1916, Stieglitz included some of O’Keeffe’s drawings in an exhibition without her knowledge or permission. When the artist learned of the exhibition, she went to New York and met with Stieglitz. The correspondence begun when O’Keeffe returned to teaching in Texas was the start of a professional and personal connection between Stieglitz and O’Keeffe. They married in 1924.

In 1917, Stieglitz mounted a solo show of O’Keeffe’s work, the first of 22 one-person shows he created to promote her work. The next year she moved to New York City at Stieglitz’s invitation and began her career as a professional artist. O’Keeffe focused on working in oil paint and, through Stieglitz, joined the circle of artists and writers who were reshaping American culture.

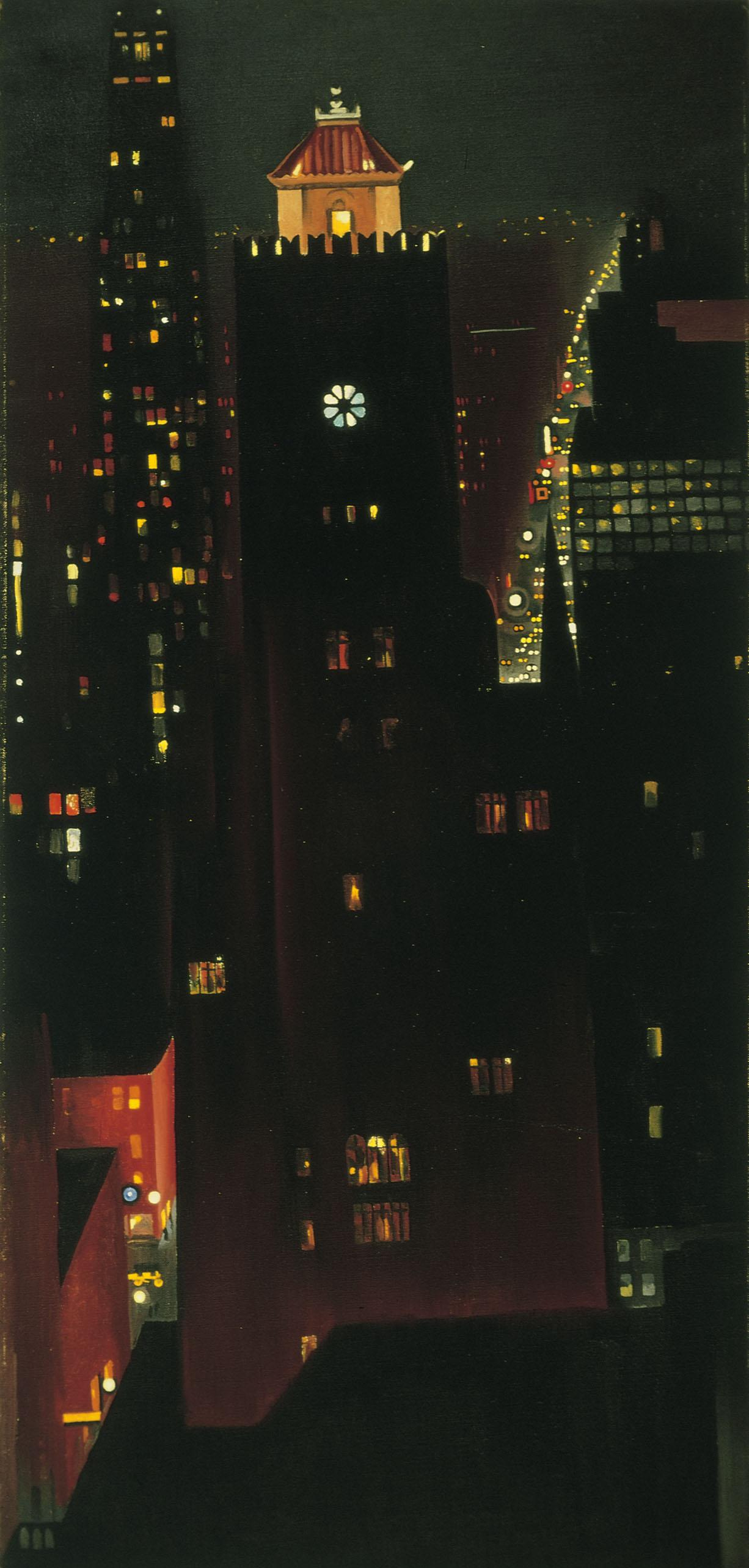

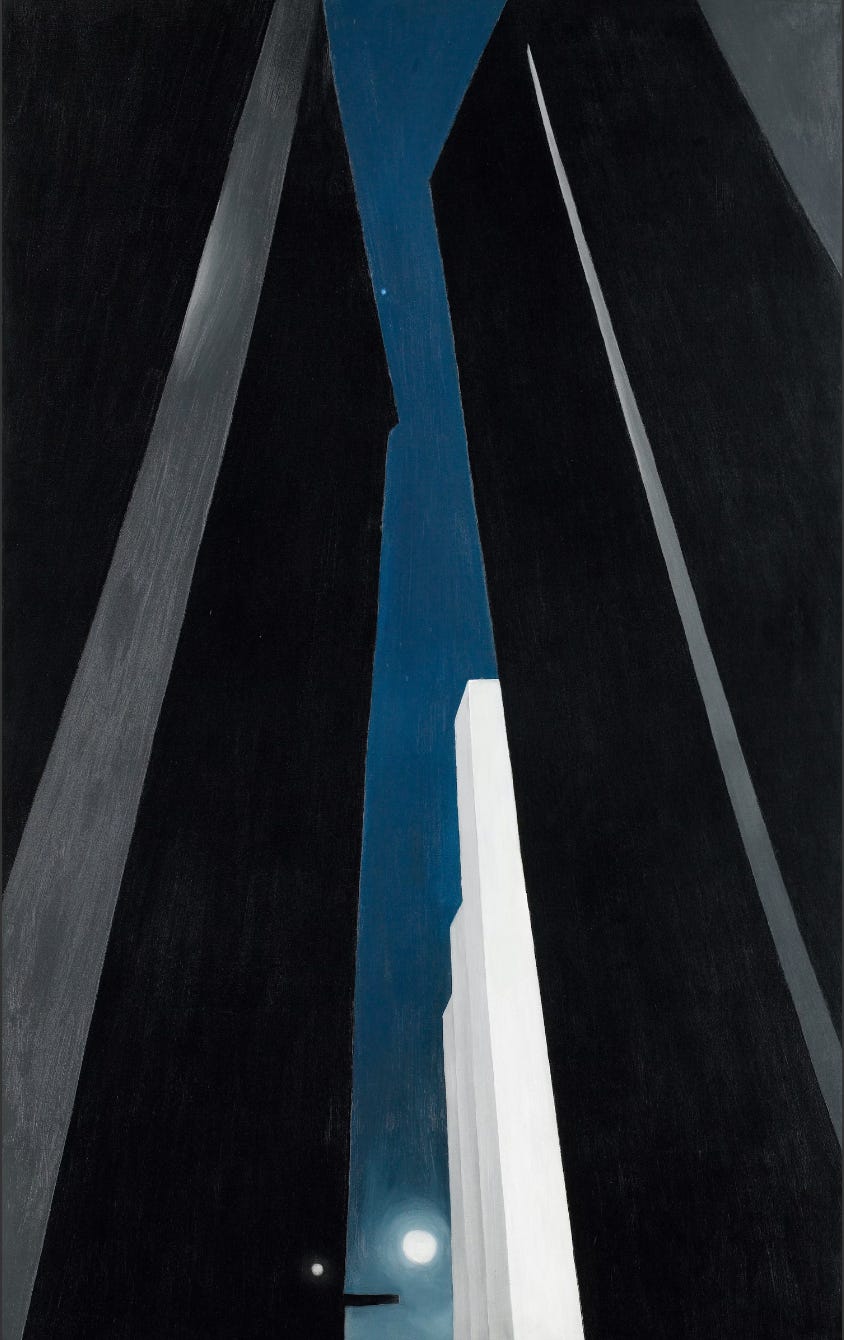

The first of O’Keeffe’s cityscapes is thought to be New York Street with Moon dated 1925 (the first image in this post). Though Stieglitz resisted exhibiting her skyscraper paintings, in 1926 he agreed to include New York Street with Moon in her solo show at The Intimate Gallery. It sold on the first day for $1000 (approximately $17,700 today). O’Keeffe later recalled “from then on they let me paint New York.”

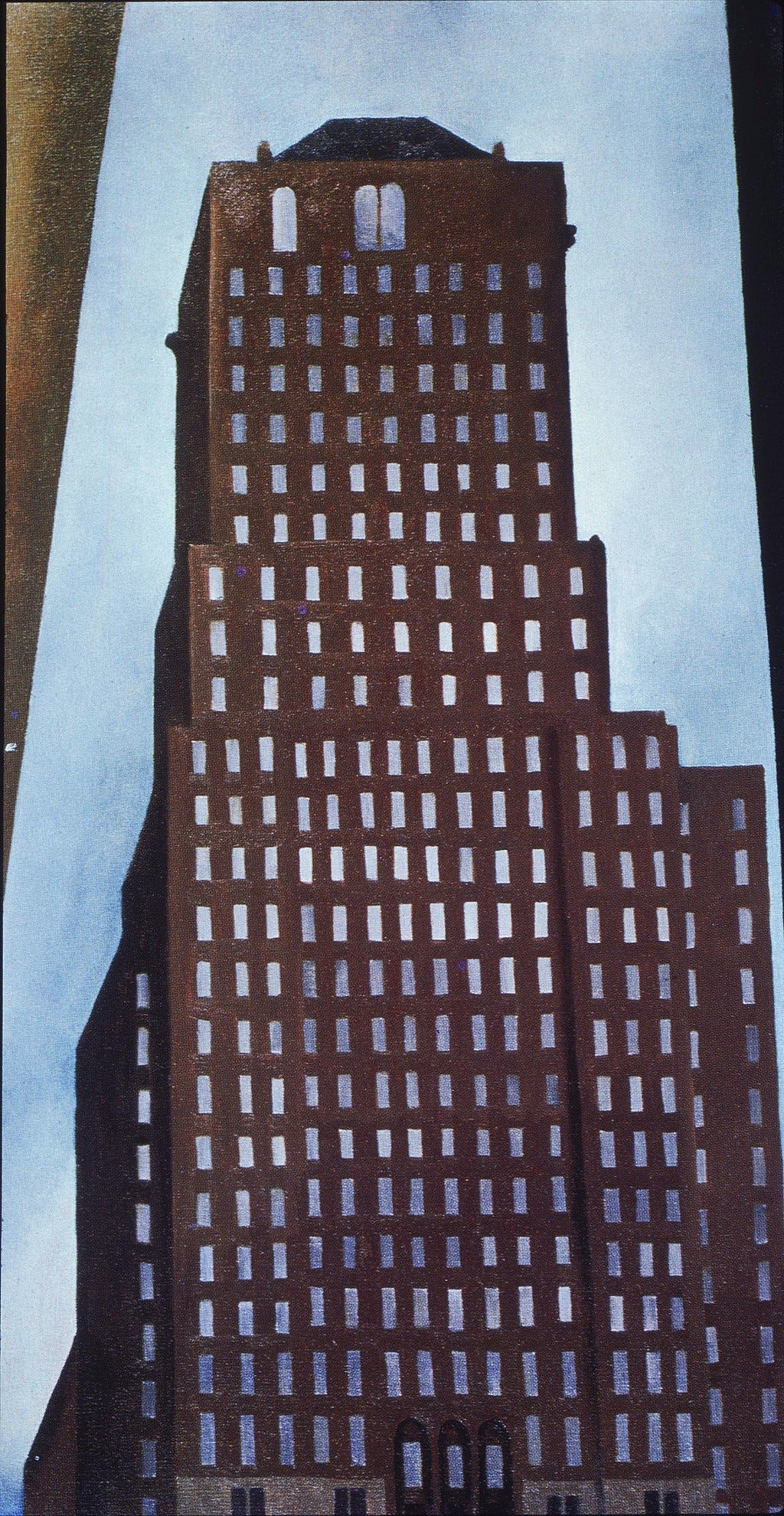

In 1925, Stieglitz and O’Keeffe moved into a 30th floor apartment in the Shelton Hotel. With the inspiration of this new perspective on the city, the artist began to explore and interpret her environment.

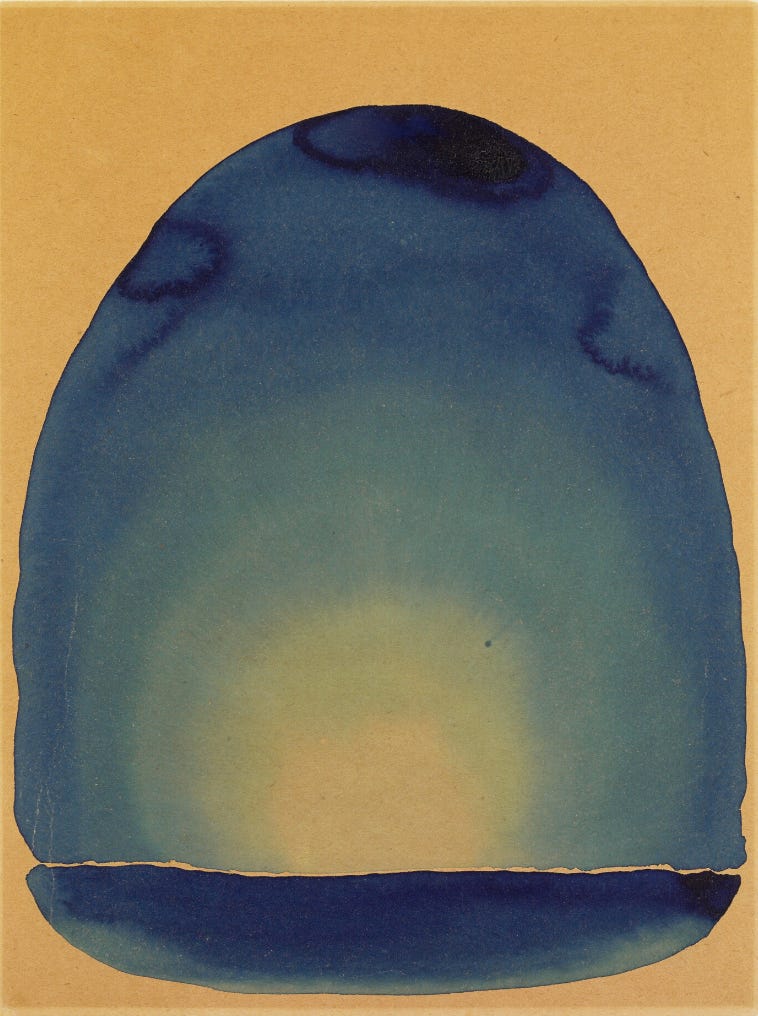

Just as blooms were transformed in the flower paintings that O’Keeffe was creating at the same time, during 1926 she transformed the realism of her home in Shelton Hotel, N.Y., No. 1 into the abstraction of The Shelton with Sunspots.

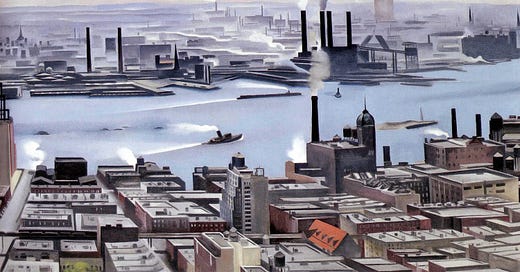

Looking out from the Shelton at the urban industrial environment across the East River resulted in eleven surviving oil paintings and pastels.

I know it's unusual for an artist to want to work way up near the roof of a big hotel, in the heart of a roaring city, but I think that's just what the artist of today needs for stimulus. … Today the city is something bigger, grander, more complex than ever before in history. There is a meaning in its strong warm grip we are all trying to grasp. And nothing can be gained by running away. I wouldn't if I could. - Georgia O’Keeffe, 1928

One of the best known of Georgia O’Keeffe’s skyscraper paintings is Radiator Building - Night, New York from 1927. Radiator Building conveys the energy and excitement of the Roaring Twenties. In this symbolic portrait, she makes Stieglitz’s presence explicit. To the left of the Radiator Building, a red neon sign, which in reality read “Scientific American,” was transformed by O’Keeffe to read “Alfred Stieglitz.”

Throughout her career, Georgia O’Keeffe responded to her surroundings. Whether in New York or New Mexico, she observed, refined, and symbolically abstracted flowers, the desert, and the city.

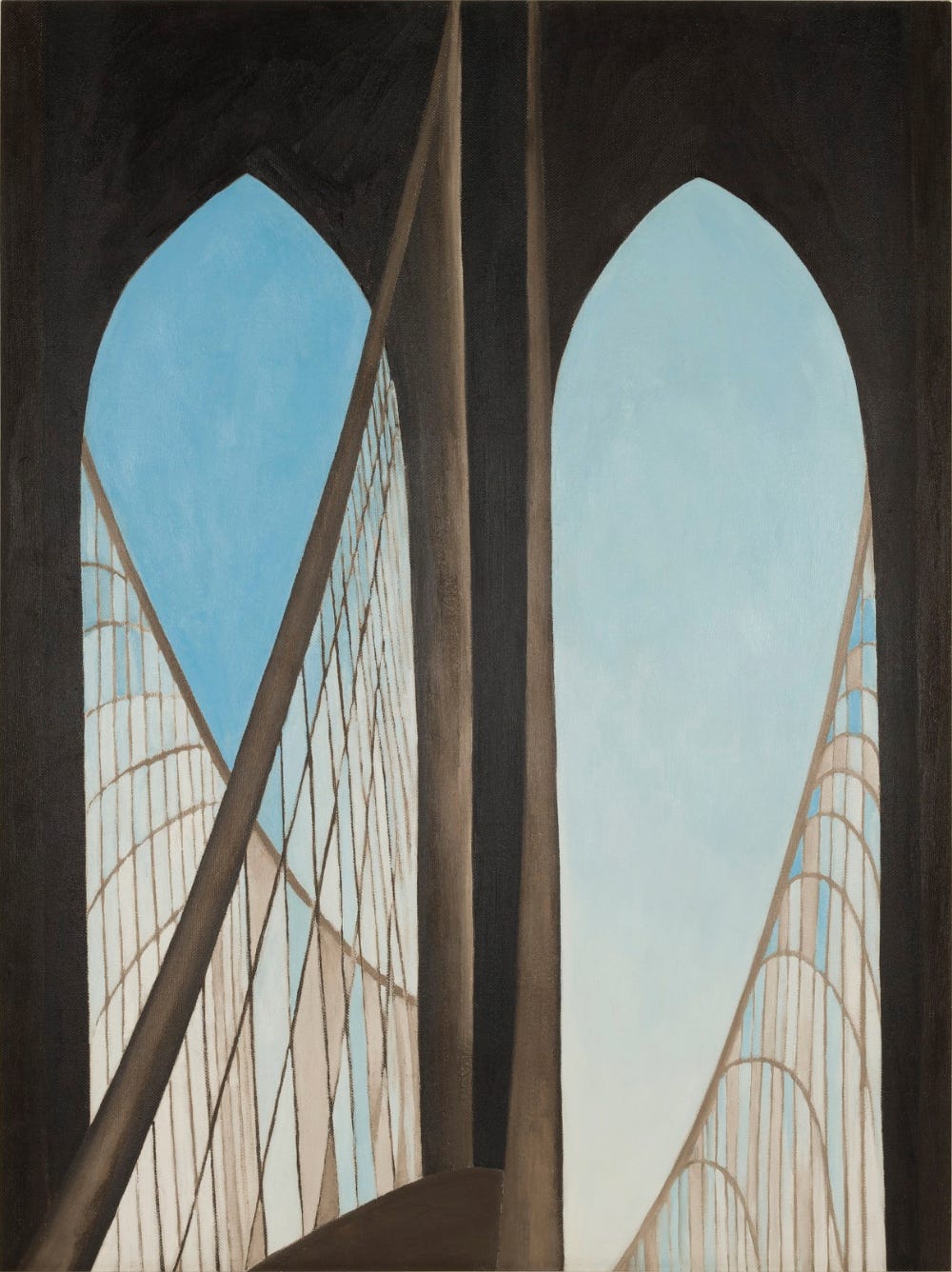

The final New York painting that O’Keeffe created was Brooklyn Bridge, completed in 1949, as the artist prepared to leave the city for good. She had returned to the New York from New Mexico in the summer of 1946, as Stieglitz was dying. The Brooklyn Museum, which owns this final New York painting, has described it as “a Valentine to what she was leaving behind.”

Though drawn to desert and rural spaces throughout her life, during O’Keeffe’s years in New York she drew inspiration from the city, often resulting in dramatic, abstracted works that place the viewer in the early modern metropolis, dwarfed by looming skyscrapers.

Georgia O’Keeffe was major force throughout the history of 20th century American art. Commanding the highest prices for an American woman in the late 1920s, today her paintings have exceeded $44 million at auction. The subject of many exhibitions around the world, O’Keeffe was the first woman artist to have a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, in 1946 and the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico was the first museum in the United States to be dedicated to a woman artist.

Georgia O’Keeffe died in 1986.

The Art Institute of Chicago exhibition “Georgia O’Keeffe: My New Yorks” opens on June 2, 2024 and continues until September 22, 2024. https://www.artic.edu/exhibitions/9539/georgia-o-keeffe-my-new-yorks

I’m taking a short break, so next week’s post will be a re-publication of one of my earlier editions. Thanks, as always, for reading.

These are very interesting paintings. I really liked most of them and my favorite was the East River.

She really was an artist of singular vision, wasn’t she? In these cityscapes, I love the way she so elegantly pares down the shapes to their sharp-angled essence.