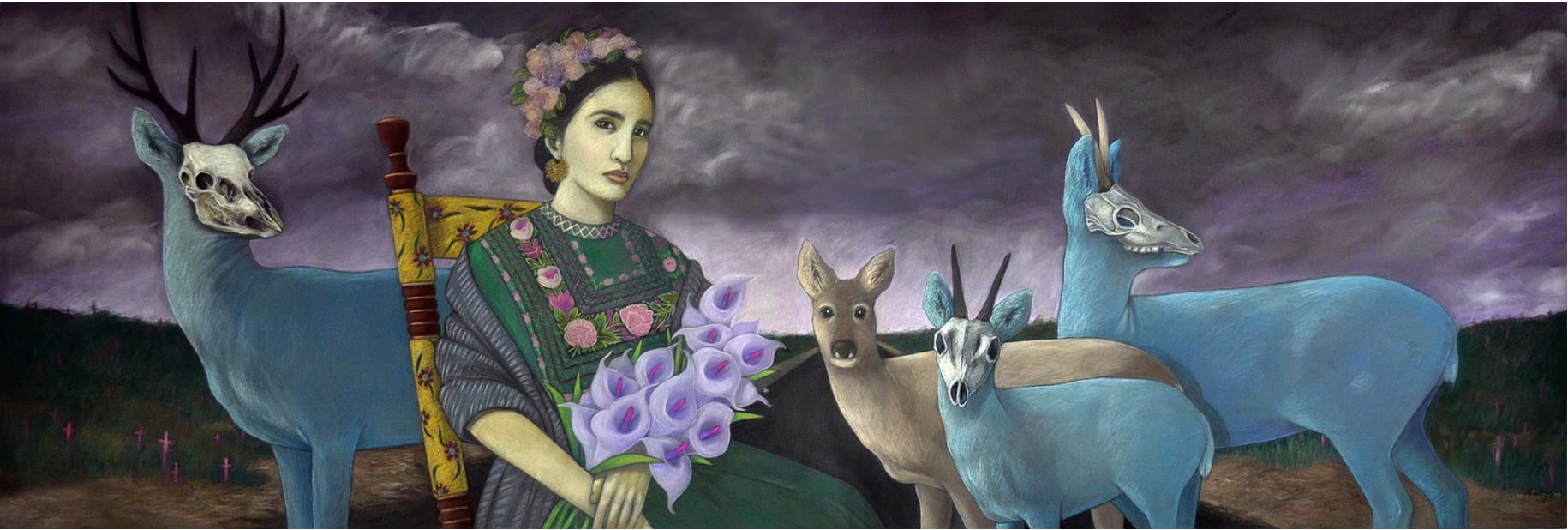

This Summer, Judithe Hernández (Chicana American, b. 1948) is receiving a long-overdue career retrospective at the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art and Culture, in Riverside, California. Featuring over 80 works spanning 50 years of painting, this large yet intimate exhibition is a unique opportunity to gain comprehensive access to this remarkable colorist’s passionate view of humanity over the entire arc of her development, in the Chicano art and political movements of the 1970s, her studio work, and present perspective as one of the principal matriarchs of Chicana/o/x art in America. Although this is a career retrospective, the exhibition’s title “Beyond Myself, Somewhere, I Wait for My Arrival,” shared with the above work, refers to the artist’s belief that she has not yet arrived but continues to work in a perpetual process of discovery and being discovered. Both the title of this exhibition and artwork were derived from a line of poetry from “The Balcony” by Octavio Paz, translated by Eliot Weinberger, from The Collected Poems 1957-1987.

The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art and Culture, affectionately known as “The Cheech,” opened in 2022 in partnership with the Riverside Art Museum and the City of Riverside. Built to preserve and exhibit the extensive private collection of actor/comedian Cheech Marin, The Cheech is one of only a handful of public art institutions dedicated exclusively to Chicana/o/x Art. The Cheech is tasked with the dual mission of preserving and exhibiting the original collection of Cheech Marin while simultaneously representing a diverse and complex, yet often ignored, American art movement. This exhibition fulfills one of artistic director María Esther Fernández’s core missions: to augment the permanent collection with a series of temporary exhibitions featuring art and artists not well-represented in the original gift.

The ground floor of this converted municipal library building houses an installation of Cheech Marin’s collection and an atrium with rotating exhibitions by local artists, while the top floor is dedicated to temporary exhibitions. Each step into The Cheech deepens the sensation that this museum is going to be exciting and different from most museum experiences. Almost all of the artwork exhibited is contemporary, from the 1980s forward. Visitors will discover artists that they are unlikely to have seen in other large public institutions in the United States, but who are deserving of their attention and interest. I felt buoyant, almost giddy, as I moved through the galleries housing the permanent collection before ascending to visit the Judithe Hernández exhibition on the second floor. Other visitors seemed equally energized, running up to artwork, pointing, and exclaiming aloud, perhaps because this is the first time many have seen themselves and their culture hanging on the walls of a public art museum.

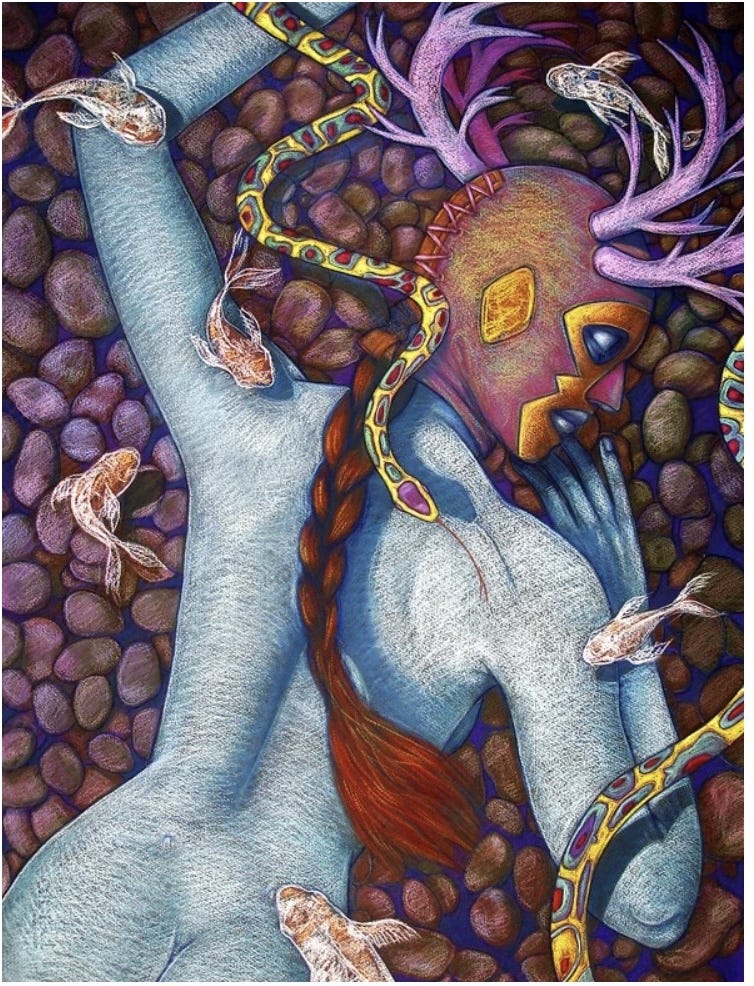

Although Hernández is frequently described as a painter or muralist, her studio practice is primarily drawing. The artist works in bright pastel on black paper which creates a luminous quality to her figures and compositions. There is a recognizable cohesion that runs through the body of work, created by repeating motifs, such as luchador masks, ribbons, deer, a red hand (variably representing divinity, power, violence, or death), as well as her self-imposed tight range of colors. The practice of focusing on a limited number of colors dates back to the artist’s student days at the prestigious Otis Art Institute (now Otis College of Art and Design) in Los Angeles. Hernández recalls the instruction of quixotic painting professor, Bentley Schaad (American, 1925–1999), who restricted students to 5 colors: ultramarine blue, sienna, raw umber, black, and white, for the entire semester in order to focus the students attention on lessons of composition, tone, and value, rather than letting color do all the work. Her stunning, expressive figures are a tribute to the influence of prominent African American artist Charles White (1918-1979), her closest mentor at Otis. White recognized in Hernández an already refined skill and gave her encouragement and the opportunity to develop expertise in figurative expression of human emotion and experience.

Hernández was born in 1948 in South Central Los Angeles and raised in the East Los Angeles neighborhood of Lincoln Heights. Her mother emphasized ambition, ability, education, and intelligence over social position, status, or wealth, contributing to her positive attitude as a smart, self-possessed, assertive Chicana artist. Her artistic talent was recognized early by middle-school and high-school teachers, who supported Hernández with her own separate studio space off of the main art room. Additionally, they encouraged her to pursue opportunities to enter into regional art competitions, including for the scholarship which allowed her to pursue her BFA and MFA degrees at Otis Art Institute.

In addition to influential mentorship from Charles White, Otis was where Hernández befriended Carlos Almarez, one of the few fellow Chicano students in the prestigious West Coast art school. The two remained close after graduation as both became immersed in the Chicano political movements of the 1970s, contributing posters and murals and participating in the creation of the graphic visual language and iconography that articulated their political stance. It is important to understand that Chicano is not a census term that a person is born into, such as Hispanic American or a social description of heritage such as Latino American or Mexican American. Rather, Chicano is a chosen, self-applied identity that simultaneously rejects the limitations and stereotypes imposed by the dominant culture and positively asserts a new and unique political, social, and cultural identity of the Chicano. Many of the first generation of Chicano artists emerged from the political movements of the 1960s and 1970s. During this period Hernández was an active participant in César Chávez’s and Dolores Huerta’s United Farm Workers of America, as well as artist organizations El Teatro Campesino (The Farmworker’s Theatre), Concilio de Arte Popular (People’s Art Council), and Centro de Arte Público (Center for Public Art).

Shortly after his graduation from Otis, Carlos Almaraz joined together with Frank Romero, Gilbert "Magu" Luján, and Robert de la Rocha to form an artist collective, Los Four, the university-trained, academic answer to the more streetwise, avant-garde Asco group that was also gaining recognition at the same time. Hernández was invited to join Los Four as the fifth overall and only female member. Because the group name already had recognition and brand value following a breakthrough into mainstream art culture with a group show at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), they remained Los Four. Unfortunately, Hernández joined the group too late to be included in the LACMA exhibition. For the remainder of the 1970’s Hernández continued both her political artwork and separate studio practice, showing in the few galleries in Los Angeles which exhibited Chicano artists. When they couldn’t find space in established galleries, the artists created their own opportunities. In 1980, Hernández relocated to Chicago to focus exclusively on her studio practice, making way for the next generation of artists to continue the political work. Shortly after, Hernández attained national recognition when she received the first solo exhibition for a west coast Chicana artist in New York City, at the Cayman Gallery. In 1989, she was one of three women artists to contribute work to “Les Démon des Anges” (The Demon of the Angels), a touring exhibition of Chicano art in Europe.

Throughout her career, Hernández’s lyrical narrative imagery is frequently described in literary terms, specifically Magical Realism, which differentiates her art from both Surrealism and classical naturalism. Magical Realism seamlessly blends elements of myth, fantasy, or magic into the mundane reality of day-to-day human life in order to reveal or accentuate a deeper truth. This artist’s goal is to first create something beautiful, an arresting image that draws the audience in with exquisitely executed color and form, that then holds them once they realize there is something more to see. The purpose of the magical elements in her work is to help viewers sustain a childlike wonder fueled by imagination and curiosity in contrast to our jaded adult perspective on life and mundane reality.

Perhaps not accidentally, the most prominent practitioners of Magical Realism in contemporary literature, such as Isabel Allende, Jorge Luis Borges, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, originate from Latin America but have universal themes that transcend language and national boundaries to reach a global audience. While Hernández’s imagery includes symbolic language and motifs frequently associated with Chicana/o/x art and culture, Hernández resists limitations imposed by mainstream cultural stereotypes that mistakenly pigeon-hole the movement as outsider art, folk art, or agitprop political art.

While Hernández selects, creates, and presents the themes and imagery, she is not overly prescriptive with regards to the viewer’s interpretation. Instead, she offers her artwork with the understanding that the viewer will bring their personal point of view to each drawing or series. Her process begins with selection of a theme, idea, or word which she then researches in depth. For example, the captivating Adam and Eve series is an exploration of human relationships from the female artist’s perspective. Adam and Eve were selected simply because they are the most famous couple in the world. The theological associations are entirely secondary to the primacy of the human experience of being in a couple.

In the Adam and Eve series, instead of retreads of familiar iconography, Hernández offers a series of intimate glimpses into their relationship rather than the complete narrative. In her approach to depicting Eve, Hernández substitutes the female perspective for the traditional male gaze, granting her archetypal woman the agency, power, and grace so often denied in traditional depictions and art historical analysis. This Eve is nobody’s puppet, weak-willed and morally corruptible by temptation or desire, nor is she merely an object presented for male appreciation. She stares straight out of the picture frame arresting the viewers’ gaze with her own, neither embarrassed nor ashamed of her nakedness or the choices she made.

The artist knows her audience will bring their own experiences and apply them to her work. For Hernández, the most elusive and hardest thing to do as an artist is to inform the audience with an idea that fascinates them in a way that no one else could. The art or idea won’t speak to everyone, but for the viewers that get it, she hopes they will receive something special. Hernández’s skillful compositions, vibrant colors, and penetrating figures present a unique vision of humanity that are at once contemporary and timeless. Visitors have an opportunity to connect with these works in an immersive setting rarely afforded Chicana artists in public exhibition spaces.

Exiting back through the permanent collection, I understood why the artistic director, María Ester Fernández chose this artist for the museum’s first single-artist career retrospective, because the exhibition helps fill an obvious gap in the permanent collection. Cheech Marin’s enthusiasm for Chicano Art led him to collect at a time when very few in the mainstream art culture were paying attention to the art and artists from this community, eventually amassing the largest private collection of Chicano Art anywhere in the world. However, like many named, single donor museums, his collection corresponds to his personal taste and interests, whereas the museum is tasked with representing the entirety of the large, diverse, and complex movement of Chicana/o/x Art and Culture. Otherwise, the museum risks distorting visitors’ perception of the art, art movement, and culture by amplifying a single person’s point of view and perhaps excluding other perspectives. One of the criticisms of Marin’s collection is the under-representation of women artists and artists from outside the geographic center of Los Angeles. The Cheech is a unique cultural institution which has the opportunity and responsibility to frame the art historical significance of Chicana/o/x Art, to shape the art world’s perception and understanding, to promote the academic value of the collection, and to positively assert Chicano identity, history, and culture within the community and in relation to mainstream history of contemporary American art. For visitors discovering the Chicana/o/x Art for the first time and for those already familiar with many of the artists in the permanent collection, the inclusion of the Judithe Hernández retrospective, from which The Cheech recently acquired two works for their permanent collection, goes a long way to correcting half of that criticism by clearly establishing Hernández as an important figure in the history of Chicana/o/x Art Movement, and also in contemporary American art as a whole. I eagerly look forward to Fernández’s next exhibition.

The exhibition at The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art and Culture, in Riverside, CA, ends August 4, 2024 (Exhibition link), and is well worth the effort to catch in person if you can. If you miss it, don’t worry; you can see individual works of art by Hernández in these major public collections: the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, Philadelphia; the National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago; the Smithsonian American Art Museum; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin; and the UCI Museum/Institute for California Art, Irvine, California.

I don't really understand them, but she does get an "A" for real art, as I of course define it.