May we be ruled by the idea of the salvation of the earth by woman, of the transcendent vocation of woman, a vocation which has been systematically concealed, thwarted, or lead astray, to our day … The time has come to value the ideas of woman at the expense of those of man, whose bankruptcy has become tumultuously evident today. – André Breton, Arcanum 17, 1944

André Breton was the charismatic leader of the original Surrealist group, established in Paris in the 1930s. In many of his writings, as above, he spoke of breaking down traditional hierarchies, including those that favored men over women. Such statements naturally led women who shared the Surrealists’ goals and practices to believe that the movement would welcome them as equal participants. Unfortunately, though women were involved in the Surrealism movement from the beginning, they were sidelined by Breton’s idealized view of women as muses, rather than active artists. The generally misogynist society in which they lived and worked influenced even the most radical Surrealist men. In the spite of the limitations their male colleagues sometimes attempted to enforce, women were more welcome in the Surrealist movement than in other avant garde groups of the time and those who joined created their own interpretations of Surrealism by using the movement’s philosophy in combination with their own experiences. This edition of Chance Encounters will focus on some of the women involved in Surrealism in its early years, demonstrating by their powerful works that they deserved a share of the spotlight from the start.

Meret Oppenheim

For decades, art history textbooks and survey courses have emphasized the dominant male figures of the Surrealist movement with only token references to the female artists. The most commonly mentioned token woman is Meret Oppenheim (German-Swiss, 1913-1985)and her sculpture Object (1936). This work certainly deserves its fame as it perfectly encapsulates the ideas of Surrealist visual art: common objects seen in an uncommon way, combinations of the pleasurable and the disorienting, and the sense of startling discovery. Oppenheim purchased an inexpensive cup, saucer, and spoon and then covered them with gazelle or impala fur. The exoticism of the fur contrasts with the ordinary familiarity of the dishes. The fur looks soft and encourages the observer to touch (or rather to want to touch, as it’s now in a museum case). At the same time, imagining drinking from this cup or placing this spoon in one’s mouth provokes discomfort or even disgust. The fur has rendered the objects useless for their intended purpose. Sculptures like Object were an important practice within Surrealism, the creation of startling objects that challenge the viewer’s expectations. (See Chance Encounters 18 for discussion of another Surrealist object, Wolfgang Paalen’s Umbrella.) Oppenheim’s Object is sometimes described as the first work by a woman to enter the collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York City, but the museum’s founding director Alfred Barr (American, 1905-1981) personally purchased the work in 1936. The museum’s board, more conservative than its director, declined the purchase and the work didn’t become part of MOMA’s permanent collection until 1963.

Oppenheim was exposed to many forms of new art, literature, and ideas during her upbringing. One of the most important influences on the artist was Carl Jung (Swiss, 1875-1961), who founded the school of analytical psychology. Following Jung’s teachings, Oppenheim recorded and analyzed her dreams throughout her life. Another important philosophy that the artist adopted from Jung was the idea of androgynous creativity, renouncing the concept of a feminine art in favor of the belief that her works simultaneously utilized both masculine and feminine aspects. At age 18, Oppenheim moved to Paris and joined the Surrealist circle. She spent five years in that intensely creative environment, creating Object during that time.

For us women, Surrealism represented a world in which we could rebel against the conventions of our upbringing, and in which imagination was a key to a more liberated lifestyle. – Meret Oppenheim

Object’s success was not without a downside for Oppenheim. It tied her to Surrealism in a way that she found creatively stifling. The artist returned to Switzerland and trained as an art conservator in order to support herself. During the 1940s and early 1950s, the artist struggled with her mental health and declined to exhibit any of her art. The artist returned to a public role in Bern in the mid 1950s after becoming involved with the art community there. For the rest of her life, Oppenheim created works that expressed her ideas of artistic defiance and freedom.

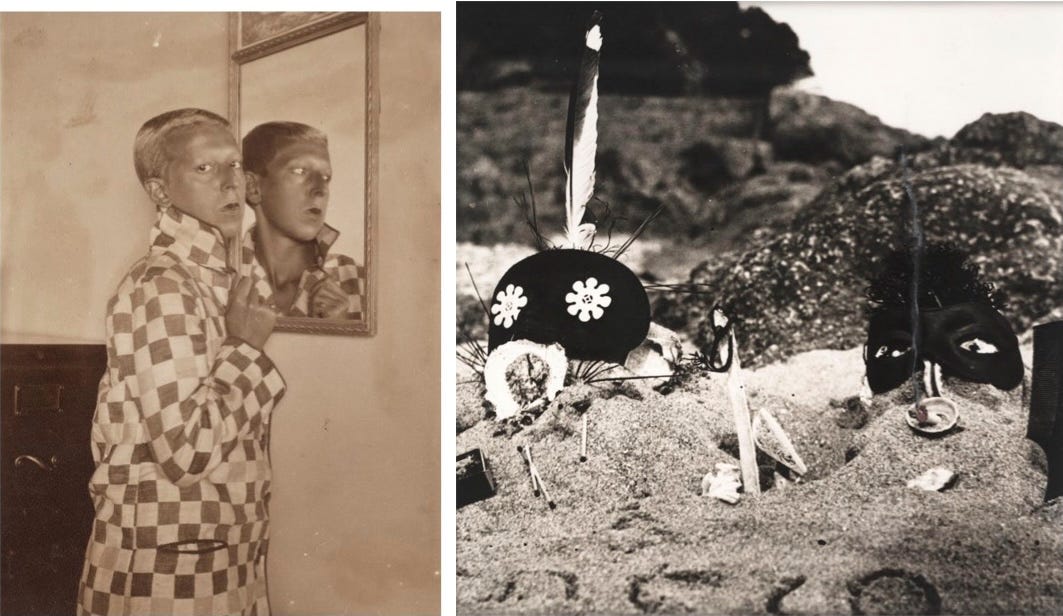

Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954) and Marcel Moore (French, 1892-1972) were romantic and artistic partners who lived their lives according to their own beliefs rather than by the established social norms. Their life together was Surrealist in both its defiance of convention and collaborative practice. Both abandoned their birth names and chose names which deliberately obscured their gender identities. Moore and Cahun met when they were in their mid-teens and the young artists encountered the Surrealist circle in Paris during the 1920s and began to attend the movement’s meetings and social events as well as hosting artistic salons of their own. Cahun produced photographs and sculptures, was a writer, and participated in avant garde theater in 1930s Paris; Moore was an illustrator, designer, and photographer. The two collaborated on many projects and though many sources identify Cahun’s images as self-portraits, recent research suggests that Moore was an active participant in the photographic projects attributed to Cahun and the person behind the camera in photos like Untitled, 1928, Cahun’s most frequently reproduced likeness. In it, Cahun has very short hair and wears a bulky patterned coat that obscures her body, yielding a figure of ambiguous gender. (In 1928, the figure would have appeared explicitly male to most observers.) The inclusion of the mirror in this photograph complicates the subject’s identity, too, by showing the face from two angles simultaneously so that the expressions appear different. Cahun said "Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me." Most photographs by Cahun (and Moore) depict her with male, androgynous, or masked identities. The variety of personas Cahun adopted in her photographs have drawn comparisons to contemporary photographer Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954) who also uses herself as a model and adopts many personas in her work. (Click to see examples from the Art Institute of Chicago collection.) A marked difference between Sherman’s works and those of Cahun and Moore is scale. Their surviving works are tiny: Untitled is just 3.6 x 2.6 inches and Entre Nous (Between Us) is only slightly larger. This suggests that the photos were made as an expression of Cahun’s explorations of identity, for private consumption rather than public display. They may also reflect the Surrealist concept of artistic play. Entre Nous (Between Us) has a more obviously playful quality with its two personages created from an arrangement of found objects propped in a sandy landscape. Play was seen by the Surrealists as an anti-rational means of unlocking one’s creativity. A variety of parlor games were popular with the Surrealists, most famously “Exquisite Corpse” in which participants created sentences or images without knowing what the other players had contributed. (See an example in Chance Encounters 33.)

Jacqueline Lamba

Jacqueline Lamba (French, 1910-1993) grew up in a suburb of Paris visiting the Louvre and the Palais Galliera, a museum of design, with her mother and sisters. After reading some of André Breton’s books, she began to visit the Surrealists’ favorite spot - Café de la Place Blanche. In 1934, Lamba met Breton, who described the artist as “scandalously beautiful” and the two were married 3 month later. From that time, Lamba created Surrealist-influenced paintings, sometimes collaborating with her husband in games of “Exquisite Corpse” and other projects. The marriage was tempestuous, with Lamba struggling against her role as Breton’s muse and the sense that she was losing her individuality as a wife and mother. Like many avant garde artists and thinkers, Berton, Lamba, and their daughter fled France after the Nazi invasion, spending seven months in Mexico and then moving to New York where Lamba had her first one woman show in 1944. The artist’s marriage to Breton broke up in 1943 and she married artist David Hare (American, 1917-1995). (See an example of Hare’s work in Chance Encounters 33.)

The object is only a part of space created by light. … Shadow does not exist, it is already light. – Jacqueline Lamba

Lamba’s works are the most abstract among the artists I chose for this edition. For the artist, light was of predominant importance. Black River (Rivière Noir) is characteristic of Lamba’s practice of translating nature into colors and patterns that convey the presence of light. The black and gray stripe of the river contrasts with two golden-tinted bands. Below, the river’s bed appears to glow with reflected light on sand and pebbles while above, strands of leafy shapes frame a golden sun-like disk. Created during her marriage to Hare, this painting reflects Lamba’s desire to express a Surrealist sense of wonder through her love of light.

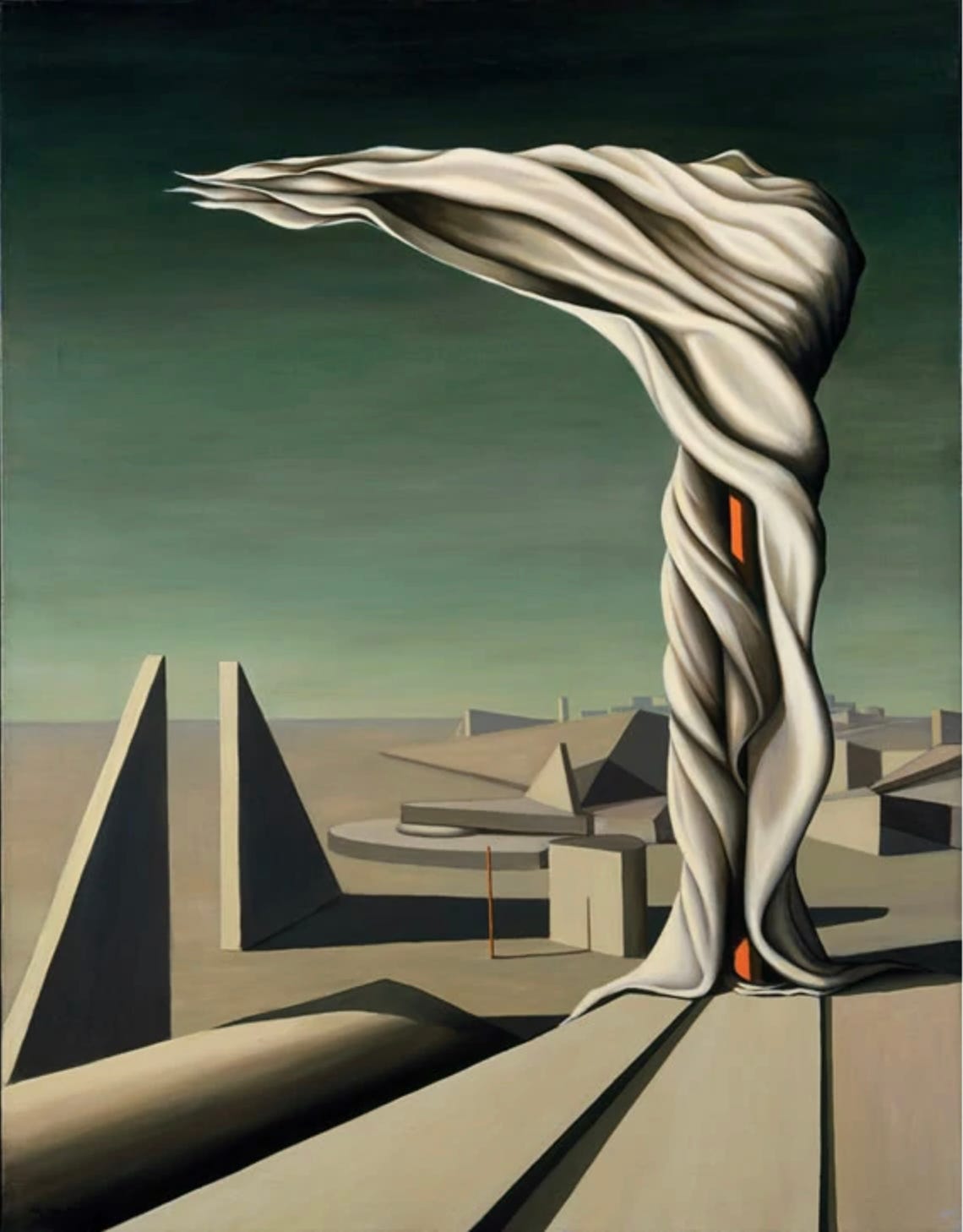

Kay Sage

American painter Kay Sage (1898-1963) created works featuring architectural elements, which she combined with desolate landscapes and figures concealed by cloth. Sage’s approach is naturalistic but her believable representations of space, texture, and light produce a disorienting and often dystopian environment. The mysterious environments in Sage’s works are a reflection of the influence of the art of Giorgio di Chirico (Italian, 1888-1978) whose work Sage first encountered in a Surrealist exhibition in 1938. I Saw Three Cities was painted in 1944 and shows a typically flat ground under a darkening greenish sky. These empty spaces often symbolized the unconscious mind in Sage’s work, an indication of the Surrealists’ fascination with psychology, especially the writings of Sigmund Freud. Strewn from the foreground into the distance of this landscape are planks, triangles, and cubes that seem meant to construct buildings, though no structures are seen. Standing among these building blocks is a figure, or at least the semblance of a figure, consisting of a red pole mostly covered in fluttering fabric. The fall of cloth along the vertical axis suggests a female form, but the glimpses inside the cloth show no body, only the pole surrounded by darkness. The flow of the cloth around and away from the pole has been identified as a reference to the Nike (Victory) of Samothrace, a famous ancient Greek sculpture (early 2nd century BCE) which Sage had seen in the Louvre. (Link.) Perhaps this figure is a reference to a robot or automaton, objects which some Surrealists found intriguing. It might also be a reference to former inhabitants who have left this place; to me, the title and date of the work suggest a reference to war-torn Europe from which Sage escaped after the German invasion of Poland in 1939. The artist used her inherited financial resources to aid fellow Surrealists in escaping from the Nazis, including the prominent painter Yves Tanguy (French, 1900-1955); the two married in 1940 after the French painter’s arrival in the United States.

Dorothea Tanning

Another important American among the early Surrealists was Dorothea Tanning (1910-2012). Raised in Illinois, Tanning quit college after two years to pursue a career as an artist. In 1935, the artist moved to New York where she supported herself as a commercial artist. Tanning first encountered Surrealism in the 1936 MOMA exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism. A few years later a gallery presented her work in solo shows and introduced her to the European Surrealists who had come to New York to escape World War 2. Artist Max Ernst (German-American, 1891-1976) who visited her studio was impressed by Birthday, a self-portrait and the two artists embarked on a friendship that developed into a romance. The artists married in 1946. The painting that drew Ernst’s attention depicts Tanning standing on a sharply tilted floor which leads to endless corridors and confusing doors. In front of the artist is a hybrid creature with a mammalian body and eagle’s wings. Furthering the strangeness of the image is the woman’s coat made up of ornate purple, gold, and lace sleeves and a mass of writhing, green human bodies. She seems oblivious too these odd features as she stares forward, as if what she sees is distant and different from what we observe. In this painting made early in her Surrealist career, Tanning captured many of the movement’s dominant themes, including the combination of the beautiful and the disconcerting, the confrontation between normal and psychological realities, and the blending of the real and the imaginary. Like Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, Tanning reinvented her own identity.

Leonor Fini

Though it began in France, Surrealism welcomed the rise of similar groups around the world, and when foreign artists chose to come to Europe, they were welcomed by the French group. Born in Argentina to an Italian mother and Argentine father, Leonor Fini (Argentine-Italian, 1907-1996) was raised in Italy by her mother who had fled her unhappy marriage with her daughter. As a teenager, Fini decided to become an artist and though she never studied formally, she spent her youth observing Italian Renaissance and Mannerist art. Beginning at the age of 17 in Milan, she was commissioned to paint portraits of dignitaries; painting portraits remained a source of financing throughout her career. From 1944 to 1972, Fini’s main work was costume design for theater, opera, and ballet. At the same time, she developed a distinctive illustration style for which she was much in demand; she often donated illustrations to help young authors just getting started. Fini’s paintings are often populated by sphinxes and other mythological and occult figures, mostly female or androgynous. Cthonian Divinity Watching Over the Sleep of a Young Man, 1947, Fini depicted a brightly lit, reclining male sleeper being guarded by a dark-skinned sphinx. Thus, this painting reverses the traditional theme of a male gaze upon a female object. The sphinx’s hair and jewelry appear to materialize from smoky clouds and the bare branch by young man’s feet, connecting her to the idea a being who manifests from and symbolizes nature. The man’s hand clutches the pink fabric tightly suggesting it might have contained a body that has slipped away, or perhaps transformed into the divine sphinx. The young man seems somewhat androgynous, common characteristic of youths in Renaissance and Mannerist art. In spite of his darkened chin, the pink fabric hides his genitals completely, his hairless chest appears to have a hint of breast tissue, and his waist narrows before widening toward his hips.

The man in my painting sleeps because he refuses the animus role of the social and constructed and has rejected the responsibility of working in society toward those ends. – Leonor Fini

Like many of Fini’s works, this painting is filled with the qualities of mystery and sensuality that both male and female Surrealists saw as the domain of women. The Surrealists as a group saw women as repositories of occult knowledge. For many of women artists, this was a source of personal power as well as a power within themselves to be drawn upon as creative artists.

Leonora Carrington

Born to a wealthy British family who intended her to become a debutante and enter into a traditional upper class marriage, Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) became a Surrealist artist with help from a few friends and family members and her own rebellious nature. At the age of 10, she saw her first Surrealist painting in Paris and later learned about the movement from a book given to her by her mother (in spite of her family’s opposition to her becoming an artist). Carrington wrote of her discovery of Surrealism that it felt “like a burning inside; you know how when something really touches you, it feels like burning.” The artist was most interested in the role of women in the creative process and, like Fini, incorporated characters from various mythologies and the occult into her work. And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur from 1953 demonstrates the precisely painted style that Carrington used. Naturalistic details combine with shifts of scale and disconcerting details to create an otherworldly scene. The title, by beginning with the word “and,” implies that we are entering into an ongoing story. Several features of the setting enhance the sense of being outside of mundane reality; ghostly plants twine up the column at left, stars and clouds float below the ceiling, and a light-filled passage where a woman dances has opened in the wall at right. These all feel less substantial than the architectural space they inhabit and less corporeal than the occupants of the space, the red-robed minotaur, two small children, two dogs, and the pink-clad, flower-headed female figure. Many crystal balls sit on the table and float in the air while a tattered rose lies on the floor. Only the standing dog notices the arrival of the dancing figure and only the minotaur sees the viewer, making one feel that they have interrupted some important ritual. The acceptance with which the children regard their strange companions adds to the sense that they understand the story they are a part of even if we do not. Carrington’s work, filled with myth and mystery, shows similarities to the visionary paintings of Hieronymus Bosch (Dutch, c. 1450-1516), an artist whose works attracted the interest of many Surrealists. (Explore Bosch’s works here.) Bosch’s strange creatures and oddly behaving characters may have been comprehensible to his contemporaries, but we no longer fully understand what they mean. Carrington’s narratives were clearly meaningful to her but our search for meaning in both works will lead us on a journey of self-discovery as well as a deeper understand of the creators and their worlds.

Remedios Varo

I close with Remedios Varo (Spanish, 1908-1963), an artist I wrote about at length last summer. Varo was a close friend of Leonora Carrington, who like Varo had settled in Mexico City during World War 2. Like Carrington, Varo painted with a precise, largely naturalistic style. Also like her friend’s approach, Varo varied scale and the behavior of physical objects to suit the narrative goals of her work. Encounter (Encuentro), painted in 1959, was acquired earlier this year by the National Galleries of Scotland, the first painting by the artist to enter the collection of a European museum. In common with many of the figures in Varo’s paintings, the woman in this work has a heart-shaped face similar to the artist’s own. Her face is pale, her arms tinted blue, and her blue dress ragged, though it floats in the air as if blown by a wind or of its own volition. She opens a box from which a doppelganger gazes back at her, though with a face that is more pink than her own. The room is bare of furniture beyond her chair and table but a built-in set of shelves occupies the back wall. A number of closed boxes, different in size but otherwise similar to the open one on the table occupy the shelves. Do these also contain replicas of the woman? Are they different personas, life stages, or aspects of the woman’s psychology? As is common in so much Surrealist art, the exact meaning is ambiguous and part of the artist’s intention is that the viewer explore the image and seek their own understanding.

Though these women came from different places and circumstances, they all found that Surrealism offered them a means of self-expression and independence. Though many of the male Surrealists expected, as André Breton did, to continue to place women on pedestals and treat them as vessels for their ideas, the women artists adopted the ideas of defiance and social revolution that their male colleagues had proposed, applying them to and expanding them in their own lives and work.

Current exhibitions celebrating the centennial of Surrealism:

“Encyclopedia: The Late Collages of Dorothea Tanning,” Kasmin Gallery, 297 10th Avenue, New York, New York, USA, until October 24, 2024 https://www.kasmingallery.com/exhibitions/383-encyclopedia-the-late-collages-of-dorothea-tanning/

“Surrealism,” Centre Pompidou, Paris, France, until January 13, 2025 https://www.centrepompidou.fr/en/program/calendar/event/gGUudFS

“Max and Jimmy Ernst: Father Son of Surrealism,” Weinstein Gallery, 444 Clementina Street, San Francisco, California, USA, until September 28, 2024 https://www.weinstein.com/exhibitions/17-max-jimmy-ernst-father-son-of-surrealism/

“Dalí: Disruption and Devotion,” Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 465 Huntington Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, until December 1, 2024 https://www.mfa.org/exhibition/dali-disruption-and-devotion

If you know of other museum or gallery exhibitions of Surrealism or of individual Surrealist artists, please let us know in the comments.

Thanks for reading. We’ll be back next week with some new art to share with you.