Chance Encounters, Edition 41

Simone Leigh: Narrative Structures in Clay and Bronze

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and the California African American Museum (CAAM) are hosting the touring exhibition of sculptures created by artist Simone Leigh (American, b. 1967) for the United States Pavilion in the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022. Leigh is the first African American woman artist selected to represent the U.S. in Venice, an honor which she recognizes; however, Leigh is quick to point out that she is not the first Black woman artist who could have exhibited in Venice. Leigh likens herself to a relay runner in a long line of Black women artists; she just happened to be holding the baton when the call came. In fact, the anonymity of their labor and artificial absence of Black women artists from our public art institutions and art histories is a central theme to her work.

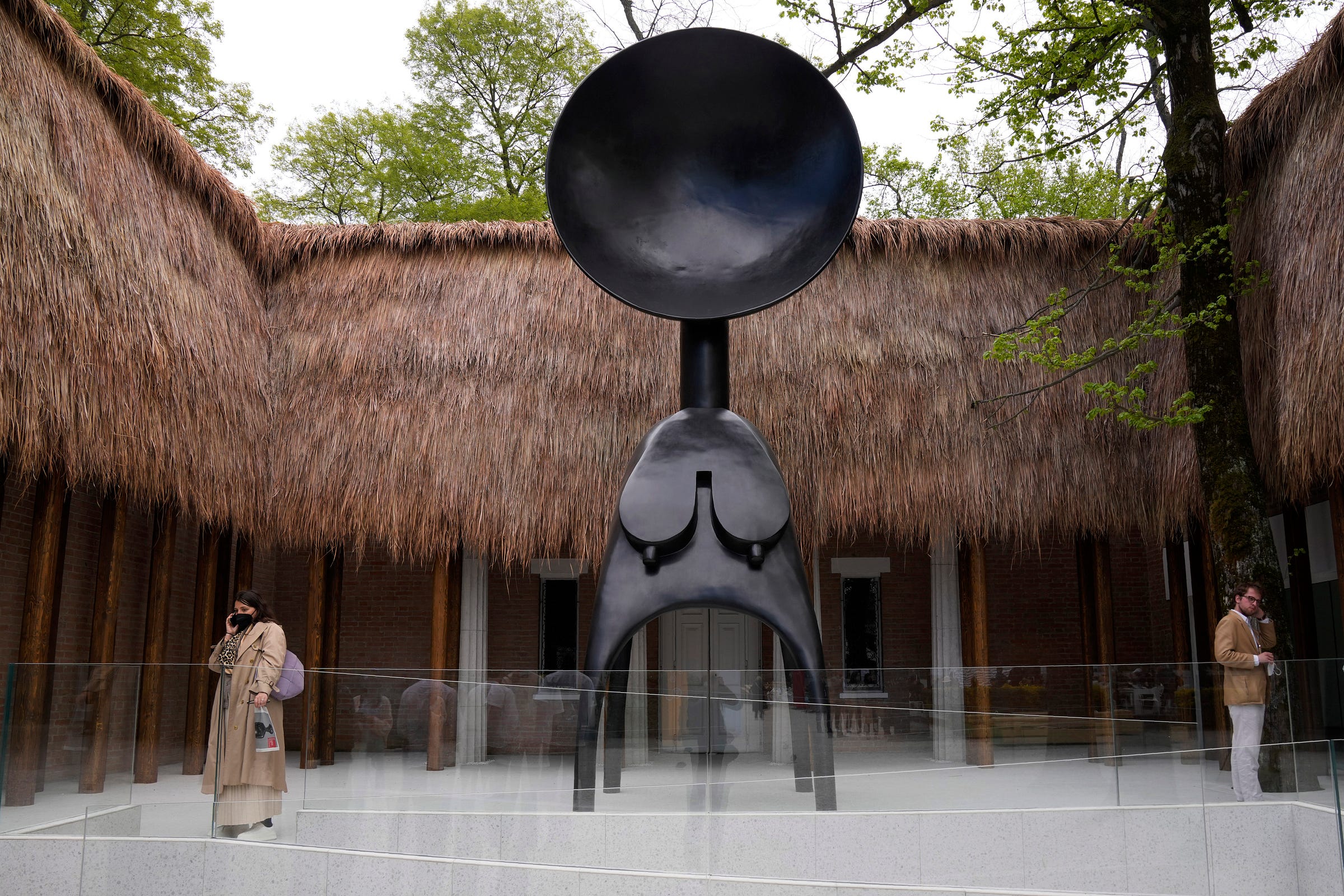

The ascendency of Simone Leigh to one of the highest honors in the art world today is not a surprise to those that have been following her career, rather the recognition seems to be the inevitable crescendo that has been building for a long time. For those unfamiliar with her work this exhibition is an opportunity to catch up. In addition to the bronze sculptures created for the Venice Biennale there are representative examples selected from her entire career. These include early ceramic work, female busts with ceramic rosettes, head/face jugs, video installations, as well as Leigh’s recurring motifs of ceramic cowrie shells, plantains, and conical wire or raffia skirts. Unfortunately, absent is her monumental bronze sculpture, Brick House (2019, see image below) which was commissioned for the prominent 10th Avenue plinth in the High Line Art Park in New York City which was awarded the Golden Lion for Best Contribution to the Biennale’s International Exhibition. However, the exhibition does not disappoint those who wish to experience works featured in Venice by one of the most prominent living American artists. The retrospective provides ample opportunity to explore Leigh’s major themes of the representation and misrepresentation of Black women in Western art, the unstable value of labor, as well as post-colonial and Black feminist theory. Meaning in her artwork is conveyed as much by her materials (clay, bronze, raffia) as by the formal elements of the sculpture.

Simone Leigh did not think of herself as an artist until her mid-thirties. She was the youngest child of Jamaican Nazarene missionaries, who immigrated to Chicago’s South Side. Although she was introduced to ceramics in high school and continued this interest at Earlham College as an Art and Philosophy major, she viewed the instability of a career in art as a liability compared with other pursuits. During a college internship at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art, she developed familiarity with African imagery, architecture, and culture, and was made acutely aware of how museums frequently categorize and display art objects created by African artists as ethnographic, cultural artifacts, attributed to regions or cultures rather than recording the names of the individual artists, an institutional convention which is both distinct from the handling of art objects created by European artists from the same time period and deprives African artists of authorship and art historical recognition.

After moving to New York, Leigh took a job in an art supply store and later taught art full-time. Leigh frequently hosted gatherings of filmmakers, writers, academics, and black feminist intellectuals at her apartment. During this period, she continued working in clay, compulsively making hundreds of ceramic water pots, a form she learned studying the career of Nigerian potter Ladi Kwali (1925-1984).

“I was obsessed with these water pots. It was a kind of perfect form…something women had been making all over the world for centuries, this anonymous labor of women.” - Simone Leigh

In 2001, she began to exhibit her ceramic work in New York galleries and group shows but was frequently reminded that ceramics were not what the contemporary art world viewed as fine art, at least not since the Post-War West Coast Clay Revolution of Peter Voulkos, John Mason, and Toshiko Takaezu. The unstable status of ceramics as an artistic medium versus decorative craft and utilitarian domestic function became an important theme to Leigh as she dug in her heels to resist hierarchies of fine art (painting, sculpture in marble and bronze, and architecture) associated with named, often male artists, as opposed to traditional craft (ceramics, textiles) typically associated with anonymous women. Leigh uses the tension of an implied preference between the unequal classifications of fine art and low craft to apply pressure to similar dichotomies encountered throughout history, such as male/female, occident/orient, developed/developing, nation/colony, as she explores issues of gender, race, and power in her work.

Between 2001 and 2009, Leigh gained a following and reputation in New York City and in 2010 her career as a full-time artist coalesced into a reality when she was awarded the prestigious artist-in-residence position at the Studio Museum in Harlem. From there she gained representation at the Jack Tilton Gallery. Each year between 2010 and 2016, Leigh added to her artistic resume with exhibitions, including at The Kitchen in Manhattan and Stuyvesant Mansion in Brooklyn. In 2016 her career accelerated with exhibitions at multiple important museums. At the Park Avenue Armory, Leigh sold out her series of female busts with ceramic rosettes, like Overburdened with Significance, during the preview. In 2019, she achieved a New York art world trifecta, winning the coveted Hugo Boss Prize and exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum, being featured at The Whitney Biennial, and being commissioned to produce a large sculpture (Brick House, above) for the High Line.

The title for her monumental bronze sculpture, Brick House, comes from a documentary film about St. Louis, a city constructed primarily in red brick, and directly references the black cultural term for an ideal woman.

“A brickhouse is a woman who’s – I hesitate to use the word strong because of stereotypes of Black women as towers of strength. It’s about the idea of an ideal woman, but very different from the Western ideal woman who is fragile. Unfortunately, I think people just relate it to the song “Brick House” by the Commodores.” – Simone Leigh

Leigh now expresses regret for the name’s association with the song, which emphasizes the woman’s figure connoting an idealized woman created as an object for male appreciation which was not the meaning Leigh intended. Instead, Leigh created a goddess figure with African features and braids, atop a large conical base. The conical shape of the base is a recurring motif in Leigh’s sculptures which is a reference to the conical architecture of the Batammaliba from Benin and Togo, teleuk dwellings of the Mousgoum people of Cameroon and Chad, and a mother’s hoop skirt under which her children seek sanctuary, all spaces of comfort and protection. In contrast, the shape also alludes to the racist architecture of “Mammy’s Cupboard” restaurants of the Jim Crow South. Multiple interpretations and references in a single form are a common objective for Leigh.

The main event of the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022 was Leigh’s exhibition titled Sovereignty and the artist’s transformation of the U.S. Pavilion which she called Façade. For Façade, Leigh covered the neoclassical Pavilion building (1930) with raffia, transforming the roofline to resemble a temporary exhibition building which had been constructed for the 1931 Paris International Exhibition in order to display European depictions of life in one of their African colonies (see below). The juxtaposition of the two contemporaneously built exhibition halls and the positioning of Satellite at the entrance set the tone for Leigh’s exhibition and informed visitors of the artist’s intention to confront and complicate the conversation of Europe’s colonial history, specifically the misrepresentation of an imagined Africa for consumption by a European audience.

The reference to Europe’s ethnographic approach to the art, artifacts, and culture of its colonies presented at the pre-eminent European fine art event directs viewers to also consider the appropriation of African imagery by early 20th century European art stars, such as Picasso, Matisse, and Kirchner. These artists created iconic modern art exhibited in Europe’s museums with their emphasis on individual authorship. This practice reinforced the idea that African imagery was merely the primitive resource material which European artistic genius reinterpreted to create unique works of contemporary “high” art. At the same time, in a separate building, the anonymous labor of African artists who crafted the source material is relegated to an exotic, ethnographic context and display, without attribution, authorship, or accolades.

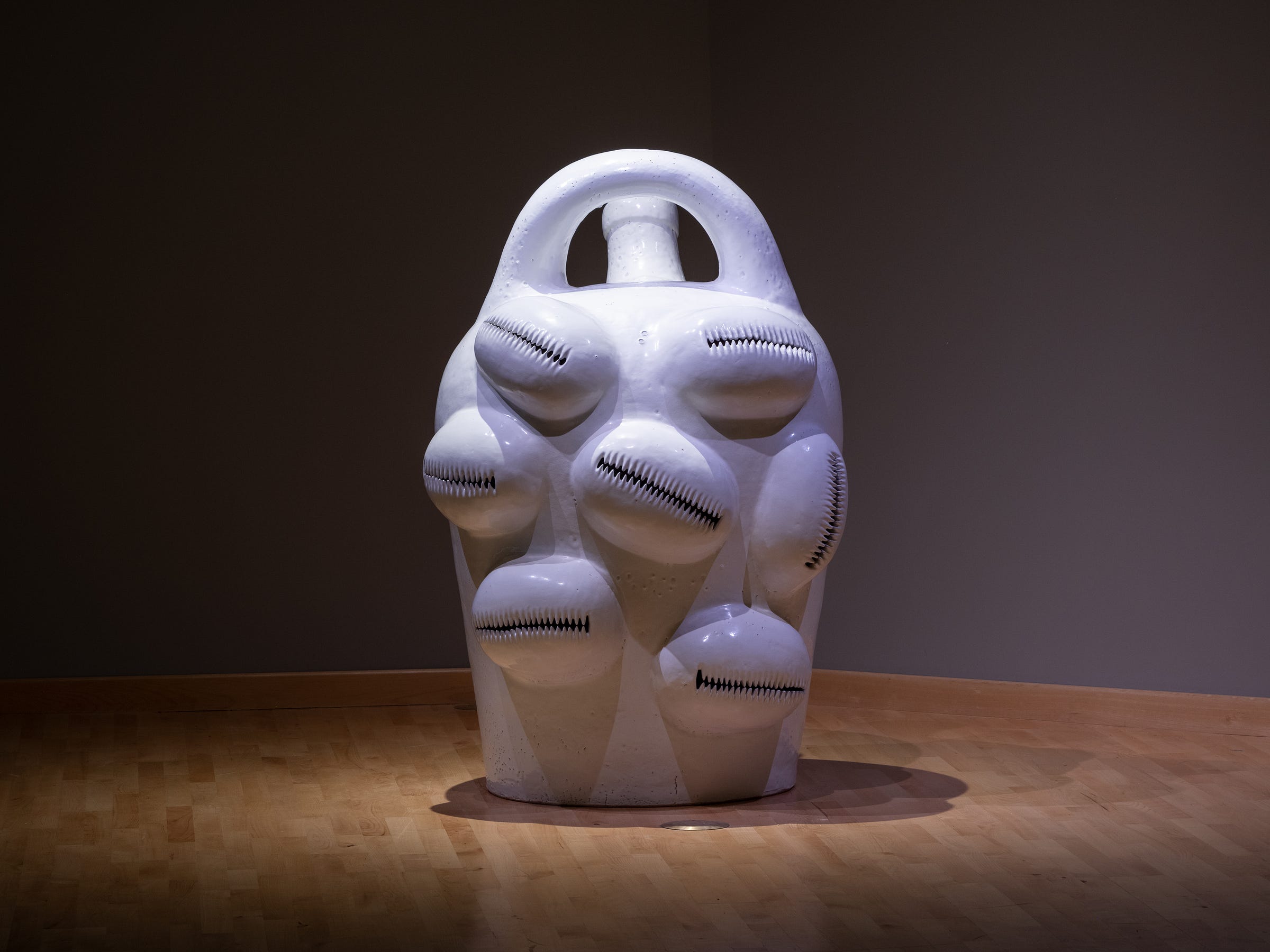

The multiplicity of references, time, and geography, as well as the radical post-colonial and Black feminist gestures embedded in Leigh’s sculptures are a significant part of the appeal. The meanings and stimulus for conversation and interpretation adds depth that rewards viewers who take the time to peel back the layers. For example, several significant works in the touring exhibition are head and face jugs, which reference the 19th century ceramic caricature art objects created by potters from the Edgefield District in South Carolina. These jugs and vessels were made first in secret by enslaved potters for their own enjoyment and later by freed Black artists for sale to the public after emancipation. By drawing our attention to the work of the Edgefield potters, the artist seeks to fill in the gaps in our museums, archives, and histories, and to complicate our conversations around gender, race, culture, and the value of labor.

In addition to literal faces and heads formed into jugs or vessels, Leigh adds cowrie shells. In many instances cowrie shells register as a stand-in for the female body in her work, but also refer to the historical use of cowrie shells as currency, sometimes in exchange for captured Africans in the transatlantic slave trade, but now these shells are sold cheaply in souvenir shops. This highlights one of Leigh’s other themes: the instability of the value that society affixes to art, people, and labor. Leigh’s cowrie shells, frequently produced with the size and shape of watermelons from which Leigh created the casts, are an intentional reference laden with additional racial meaning, history, and significance. In this way, the cowrie shell connects Leigh’s work to past misrepresentation of Black women’s bodies in art and its attendant negative associations. By creating a new beautiful form, Leigh’s cowrie shell sculptures resist the racist stereotypes of previous representations.

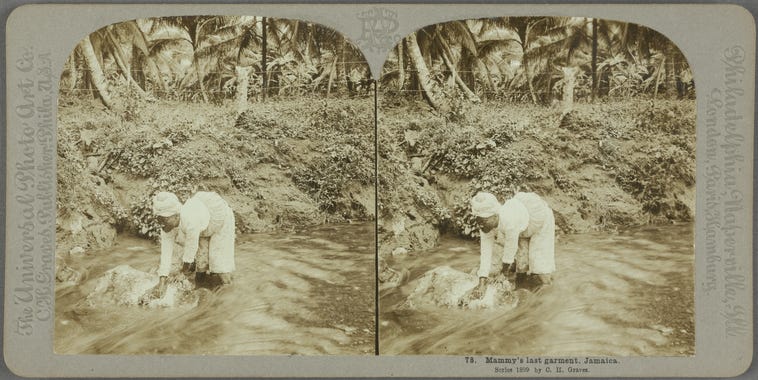

The souvenir is also the focus of one of Leigh’s most captivating sculptures, The Last Garment, 2022 (see below). Created first in clay then cast in bronze, The Last Garment features a Jamaican woman washing a shirt on a rock, in a river represented by a rectangular reflecting pool in which the sculpture is situated. The image is derived from a stereographic postcard, Mammy’s Last Garment, Jamaica, produced by American photographer C.H. Graves (1867-1943) in 1899, to be sold as a souvenir to American and European visitors. This image was widely circulated in the US and Europe to promote tourism, trade and business investment in the British West Indies and was meant to depict domestic labor by the “clean, disciplined, unthreatening” population of laborers. Often this was the only image of Jamaica seen by the intended audience. By referencing the souvenir as a seemingly harmless trinket which in fact has serious harmful implications, Leigh’s sculpture confronts viewers with the imbalance of power inherent in our colonial legacies which made use of the anonymous labor of the Afro-Caribbean population while at the same time reinforcing racist cultural stereotypes to promote tourism and trade.

Leigh’s work is beautiful and can be enjoyed and appreciated solely for its formal, aesthetic qualities. Some of the references in the works are explicit, while others may only be recognizable to viewers already familiar with post-colonial and Black feminist theory. That would not be an impediment to a satisfying viewing of the exhibition. The presence of layered meaning, art historical references, and radical gestures in the work can richly reward viewers who are interested in these issues and who want to examine Leigh’s body of work in the context in which it was created. For those wishing to investigate further, the accompanying catalogue produced for the touring exhibition by the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, contains extensive essays addressing many of the issues and embedded references found in Leigh’s sculpture.

”Simone Leigh” at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 5905 Wilshire Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90036 (https://www.lacma.org/art/exhibition/simone-leigh) and California African American Museum, Exposition Park, 600 State Dr, Los Angeles, CA 90037 (https://caamuseum.org/exhibitions/2024/simone-leigh), will continue through January 20, 2025.

Simone Leigh is represented by Matthew Marks Gallery, New York and Los Angeles. https://matthewmarks.com/artists/simone-leigh

She's really good, isn't she? Her sculptural shapes are so substantial. They look here like they must have a powerful presence. I hope to take in the shows, soon. I bet it'll be elevating. Thanks for your clear presentation of her work and career.

I had seen very little of her work before; what a fantastic survey of her career and the way she enfolds many layers of meaning I to the works. Thank you!