I love the Fall: the changing colors; the sound and scent of fallen leaves; the golden light that marks the time of year. In honor of the arrival of the season, I’ve collected some art in which artists have shared their interpretations of autumn.

Grace Hartigan (American, 1922-2008) was one of several women who were prominent members of the Abstract Expressionist movement in the mid-20th century United States. In spite of the active role they played in the movement, women artists like Hartigan tended to be ignored or disregarded when it came to exhibitions and publicity. It so frustrated the artist that for a time in the early 1950s she exhibited her works as by “George Hartigan” in hopes of countering this prejudice. Just a few years after she returned to using her own name, Hartigan was the only woman of the many then working to be included in a large exhibition called “New American Painting,” organized by the Museum of Modern Art in New York; the exhibition traveled through Europe from 1956 to 1958, helping establish Abstract Expressionism as a significant movement internationally. Autumn Shop Window was created in the 1970s when the artist’s work was characterized by shallow space crowded with recognizable objects. The intersecting and overlapping outlines derive from the artist’s interest in Cubism while the jumble of images suggests the experience of walking through a busy shopping district. The patches of color often don’t follow the outlines, adding to the energy of the composition. Finally, Hartigan’s palette of yellows, oranges, and reds contrasted with areas of blue speak of Fall, even before one sees the title.

A similar palette appears, in a very different style, in Autumn Effect at Argenteuil by Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926). One of the leading members of the Impressionist movement, Monet was fascinated by the interactions of light and atmosphere and the ways that these altered his perceptions of the world. This painting was created during a five year period when the artist and his family were living in Argenteuil, in the northwestern suburbs of Paris. During this period, Monet owned a small sailboat which he had set up as a painting studio; he spent many hours floating on the Seine capturing the landscape under different weather conditions. (Friend and fellow artist Édouard Manet (French, 1832-1883) painted Monet in his studio-boat in 1874.) Some of Monet’s innovative painting techniques, adopted to capture the effects he was observing, are seen in this painting. The first of these is the instinctive application of paint, in which the artist changes the size and shape of brushstrokes to match the texture of the object he is representing.

The second is Monet’s broken color technique, seen the detail on the left, above. In broken color, the artist applies block-like, obvious strokes of different colors to capture the swiftly changing colors of the subject. Monet was especially fond of using this technique when he was painting water; it appears in Impression: Sunrise (1872) from which the movement was given its name, and in the series of Water Lilies painted late in the artist’s life. Finally, to capture the thin branches among the leaves of the tree on the right, Monet flipped his brush and scratched through the paint, as seen in the right detail above. The artist has invited us into his little studio-boat, afloat on the Seine, looking toward Argenteuil framed by the fluttering foliage of early Fall.

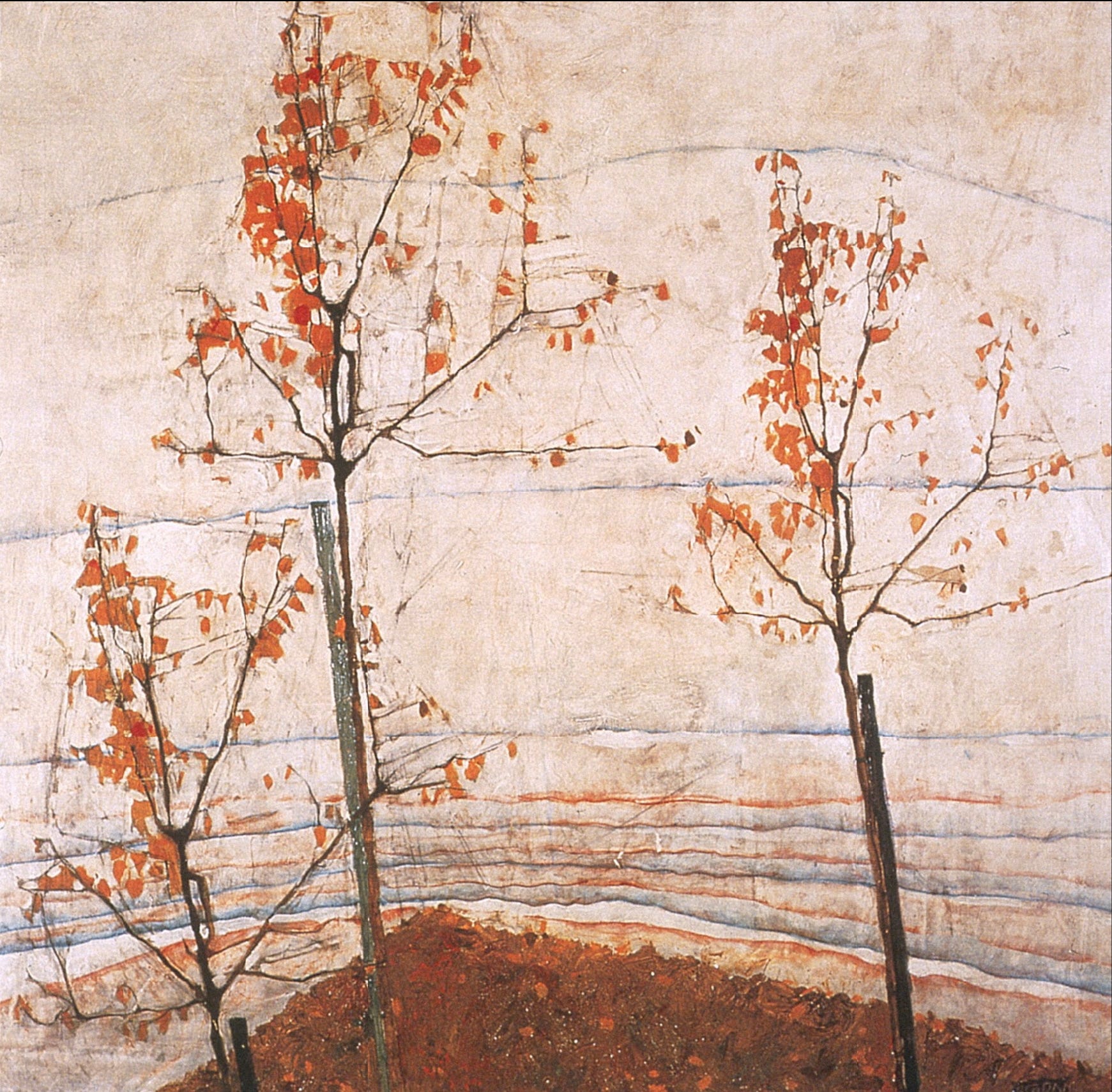

Autumn Trees, painted by Austrian artist Egon Schiele (1890-1918) in 1911, captures the change of season with the artist’s characteristic spare, Expressionist approach. The young Schiele had approached his much older fellow Austrian, Gustav Klimt (1962-1918) and Klimt had been helpful to him, exchanging drawings with the younger artist, introducing him to other artists, and helping him to find models. Even after being conscripted into the army during World War One, Schiele was able to continue painting and saw success in Germany, Poland, and Austria in spite of the war. Having been discharged from the army, Schiele had a selection of works included in the 49th Secession Exhibition (1918) which was well received. Unfortunately, along with his mentor Klimt, the artist, his wife, and unborn child perished in the Spanish Influenza Epidemic in 1918.

Painted when Schiele was only 21 years old, Autumn Trees includes the twisting, wiry line with which the artist captured nearly everything he depicted. At first glance, this work seems to depict some recently planted trees at the corner of a yard but when we look beyond the turf, the setting disappears in a pale peach-colored space sliced into bands by thin blue and orange streaks. The spindly trees, tilting to the left in spite of the stakes supporting them, and the abstract background suggest the melancholy that sometimes comes with the Autumn season. The use of nature as a reflection of human feelings is typical of the Expressionist movement with which Schiele is often associated.

A different Autumn mood is captured in the poem “October” by Paul Lawrence Dunbar (American, 1872-1906). Like Schiele, Dunbar was something of prodigy, giving his first recital at age 9 and publishing his first poem at age 16. The author even developed an international reputation, one of the first American Black authors to do so. This poem was published, posthumously, in 1913.

October

by Paul Lawrence Dunbar

October is the treasurer of the year,

And all the months pay bounty to her store;

The fields and orchards still their tribute bear,

And fill her brimming coffers more and more

But she, with youthful lavishness,

Spends all her wealth in gaudy dress,

And decks herself in garments bold

Of scarlet, purple, red, and gold.

She heedeth not how swift the hours fly,

But smiles and sings her happy life along;

She only sees above a shining sky;

She only hears the breezes’ voice in song.

Her garments trail the woodlands through,

And gather pearls of early dew

That sparkle, till the roguish Sun

Creeps up and steals them every one.

But what cares she that jewels should be lost,

When all of Nature’s bounteous wealth is hers?

Though princely fortunes may have been their cost,

Not one regret her calm demeanor stirs.

Whole-hearted, happy, careless, free,

She lives her life out joyously,

Nor cares when Frost stalks o’er her way

And turns her auburn locks to gray.

Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) was painted in October of 1950 by Jackson Pollock (American, 1912-1956). At over 8 feet by over 17 feet, Autumn Rhythm is one of Pollock’s largest paintings. For Pollock, the large scale of his paintings was essential to create an immersive environment in which the viewer would be “in” the painting to approximate the way the artist felt himself to be in the painting as he created it. It is this quality that makes any reproduction of a Pollock painting a weak substitute for viewing his work in person. I never liked or understood Pollock’s work until I experienced it in person. Still, looking at reproductions and learning what the artist intended allows us to prepare for the experience of the work in real life. One is surrounded by swaths of paint which, though they are long dry, suggest their original liquid nature. I become absorbed in following a particular color, with deciphering the layers of paint, and in what Pollock described as "motion made visible memories, arrested in space." Part of this painting’s creation was documented in photos and film of Pollock at work captured by Hans Namuth (German-American, 1915-1990). Thus we know that Pollock began working with the right third, laying down black, then the other colors: white; browns; and a little teal blue. The artist moved on to the central third, following the same process, then completed the last third. As was his habit, the canvas was spread on the ground and Pollock moved around the canvas, working from all sides. This three-part creation is apparent when looking at the reproduction (in person, it might not be so clear). The left third is defined by a heavy black line moving diagonally across the top and by a white curve starting at the black line, swelling toward the right and then curving back in the lower half. The right third is also defined by black and white, with upright black streaks moving from the center toward the top of the canvas and skeins of white throughout the section. There are fewer emphatic streaks of black in the central third and the white appears at the top and bottom, but very little in the center. Pollock’s work is a combination of the controlled and the uncontrollable; the artist knew what his paint would do when applied with one of his tools but its liquid nature meant that it could act in unexpected ways. The artist embraced this as allowing the painting’s own life to “come through.”

Another artist who embraces the role of chance in his work is Sam Falls (American, b. 1984). Like Pollock, Falls spreads a large canvas on the ground but instead of applying paint, he strews local foliage and flowers, even rocks and sticks, across the surface, along with cold water-activated dyes. He then leaves the whole thing for days, months, or even years. Rain and dew falling on the surface activate the dyes; the wind may move the plant materials about. To Falls, nature’s hand is at work in his art and he is capturing the place and especially the passage of time in his compositions. Falls began his career as a photographer, seeking a way to create photographs that didn’t depend on the technologies on which contemporary photography relies. He did this by leaving objects on light sensitive or colored papers, by exposing rolls of paper to sunlight for extended periods, and similar experiments. During a visit to his mother, she introduced the artist to cold-water dyes which she used to dye silk. He began experiment with them, eventually leading to works like Im on fire. In this case, you can see where some of the plant materials look almost white (the natural color of the canvas), but in other areas the dyes have almost filled the canvas, leaving only faint traces of the original shapes. In spite of his innovative technique, Falls uses the same palette of oranges, yellows, reds and with touches of blue that we saw in the paintings by Grace Hartigan and Claude Monet.

The materials of nature are at the heart of the artistic practice of Andy Goldsworthy (English, b. 1956). Though he also creates permanent structures, much of Goldsworthy’s art is temporary. Sumach leaves laid around a hole is an example of one of these ephemeral works. Holes have been an important theme for the artist since his early works in nature. To Goldsworthy, the hole represents the energies within the earth; the blackness contrasts strongly with the brightly colored leaves so that those energies become visible, at least briefly while Goldsworthy’s construction persists. When creating temporary works in nature, the artist uses no manmade tools, instead depending on his hands, teeth, and found tools to manipulate and secure his materials. In this work, sumach leaves collected on the grounds of Storm King Art Center in New Windsor, New York, were arranged around the hole. The leaves had to be sorted by color and layered around the hole from deepest red to brightest yellow. Spread across the ground at random, these colors lose their intensity and though one leaf may catch our eyes momentarily, once gathered and composed by Goldsworthy they become something truly spectacular. Photography is an important part of the artist’s practice. The photograph preserves the labor-intensive project at the moment of perfection, a moment which might be lost in the blink of an eye.

Each work grows, stays, decays – integral parts of a cycle which the photograph shows at its heights, marking the moment when the work is most alive. There is an intensity about a work at its peak that I hope is expressed in the image. Process and decay are implicit. – Andy Goldsworthy

From artists who work in wholly innovative modes with materials unimagined in the past, we turn our attention to a Chinese artist who continued a long tradition within his country. Cui Zifan (1915-2011, pronounced Tswee Zih-fahn) was heir to the eccentric ink painting tradition in China, which dated back to at least the 16th century. Chinese painting had established rules as early as the 5th century, but these rules were expressed in terms which could be reinterpreted according to changing tastes and individual teachings. Even so, the eccentric painters chose much bolder brushwork and less structured compositions than their predecessors and each succeeding generation of eccentrics sought their own forms of self-expression. Cui was the student of Qi Baishi (1864–1957, pronounced Chee Bye-shih) who was known for his naturalistic but individualistic images of small moments from nature. Qi was a popular and influential artist in post-revolutionary China and his encouragement helped Cui develop his own style and find a way to be an artist alongside duties as a public servant. In Lotus Pond in Autumn, Cui uses the blackest of ink for much of the painting, balancing those deep blacks with the red flowers and areas of unpainted paper. The seed pods create a falling and rising line of structured forms, in contrast to the irregular blotches of black that surround them. The painting conveys the ideas of a lotus plants changing with the season without depicting the objects in a literal, realistic style. In this way, Cui creates something personal and individualistic even while working within the traditions of Chinese painting.

I close with George Inness (American, 1825-1894), an artist whose work became increasingly less detailed and more expressive as he aged. Sunny Autumn Day was painted only two years before the artist’s death and represents his late style. The artist had a career that lasted 50 years and created over a thousand paintings in that time. He began in a Romantic-Realistic style derived from the American Hudson River School and the French Barbizon painters. Both groups saw landscape as a means of conveying ideas about human beings, their goals, and emotions. Artists of the Hudson River School tended to romanticize and perfect the landscapes that they depicted, while the Barbizon artists, working in and near the Fontainebleau Forest, moved away from Romanticism toward more literal depictions of the scenes they chose. In his early works, Inness tended toward realistic depictions of the landscape, but saw within nature a metaphor for human spirituality. This idea became increasingly important to the artist and he gradually stopped working outdoors. Working in his studio, from memories of his long experience with nature, Inness’ works became blurrier focusing on expressing his mystical ideas about the power of both nature and art. In spite of this emphasis on spirituality, Inness did not neglect his training in the mathematical basis of composition and color theory. In Sunny Autumn Day, the artist constricted a composition that balances the dark foreground with the bright distance, presenting that light area as a destination for the viewer to strive toward. The color palette combines the red-oranges, sunny yellows, and blues that remind us of autumn leaves and skies, the same palette used by so many artists in this edition of Chance Encounters.

Happy Fall! I hope you’ve found some autumnal inspiration here. Thank you for reading and for your comments on and shares of our work.

Such a wonderful, varied autumn collection! And, as always, your accompanying commentary offers deeper ways of seeing and understanding the art. Thank you!

Some nice art, but of course I LOVED the George Inness piece especially. Thanks for sharing these with us.