Titus Kaphar (American, b. 1976) is one of the hottest artists practicing in the United States today. He received his MFA from Yale School of Art in 2006 and entered into the prestigious artist-in-residence program at Harlem’s Studio Museum the same year. His artwork has been featured on the cover of Time Magazine, as well as appearing in the National Portrait Gallery, Art Institute of Chicago, Museum of Modern Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and many other top cultural institutions. Kaphar gave a highly regarded TEDtalk in 2017, received a MacArthur Fellowship (also known as a genius grant) in 2018, and co-founded a non-profit, artist/curator internship/mentorship program, NXTHVN, in 2020. Taking on an additional role as film-maker, his short documentary, Shut Up and Paint (2022) was shortlisted for an Academy Award. Most recently he wrote and directed his first feature film, Exhibiting Forgiveness, which debuted at Sundance earlier this year and is presently in wide release. The paintings featured in the film are currently on exhibit at the Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills, California, which has represented the artist since 2020.

These cultural achievements across multiple modes of expression are even more impressive considering Kaphar did not show an interest in art before his mid-20s and did not make his first painting until age 27. In fact, nothing about his childhood history suggested future success and a brilliant career as an artist. His mother was only 15 years old when he was born. He grew up in a working-class neighborhood in Kalamazoo, Michigan outside of Detroit. Kaphar’s estranged father has been in and out of prison most of his life. His high school GPA was a shockingly low 0.65. Going to art museums or thinking about art and art history was not part of Kaphar’s early life experience. That all turned around when he signed up for Junior College to demonstrate a commitment to his future in order to get a date with his future wife. According to Kaphar, he wasn’t paying much attention to what courses he had signed up for, but one was Art History, the kind of survey course that covers everything from cave paintings through Jackson Pollock in a single semester. In that course, the entirety of black representation (either as subject or artist) was limited to a 14-page chapter in the textbook and one day of lecture, both of which were skipped by the teacher because they did not have time.

It became clear that if I wanted to know that history I was going to have to seek it out on my own…to create a narrative that I didn’t see or hear. -- Titus Kaphar

Kaphar’s early art practice centered on the subject of black representation in the western art canon. One of his most famous works from this period, Behind the Myth of Benevolence (2014), features a dual portrait of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings. The title is derived from a conversation with a well-respected history teacher, who referred to Jefferson as a “benevolent slave owner.” This description both shocked and confused Kaphar and his follow up questions for clarification were met with a long silence that ended the conversation. Kaphar returned to his studio and started painting. Consistent with much of his artwork from this period, the artist does not limit himself to a single flat surface covered in colored pigment, instead the canvas is manipulated, torn, cut, and folded to expose underlayers or wood supports. In this way, Kaphar’s paintings become a more complicated three-dimensional object that reflects the multi-layered narrative of history itself. In Behind the Myth of Benevolence, a large formal portrait of Jefferson appears on the top canvas which has had the staples removed from the wooden support on two sides, so it falls away to reveal an under-canvas with a portrait of Sally Hemings emerging from her bath.

If we are not honest about our past, then we cannot have a clear direction towards our future. -- Titus Kaphar

Kaphar rejects the binary conversation surrounding what to do with our nation’s public sculptures, monuments, and artwork from difficult and complicated periods in our history. He does not accept limiting our response to two choices: leave them up or take them down. Instead, the artist offers a third option, which is to create new artwork in conversation with what already exists. His intent is not to erase history or replace previous depictions of historical figures, rather he hopes to amend history the same way we amend the Constitution, leave the original text but add to it new phrasing that applies to our present situation and future aspirations. By creating artwork which addresses the past with new depictions in a historical context, Kaphar hopes to reveal hidden histories and untold stories in order to give them contemporary relevance and lay bare the impact of art on our understanding of history, as well as on our present and future.

For example, in Shifting the Gaze (2017), which he completed on stage during his 2017 TEDtalk, Kaphar recreated a 17th century portrait of a wealthy white family that included an unidentified and unremembered black servant in the source painting (Family Group in a Landscape by Hals, Frans. Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza). The artist then painted over the more dominant figures in the image using white paint mixed in linseed oil. This material will become more transparent over time, eventually restoring the original composition and figure hierarchy. As Kaphar explains, in historical paintings everything included by the artist, from the positioning and height of the main figures to the lace pattern and silk brocade, has a purpose that conveys meaning. This includes the representation of black people. By painting over the other figures in semi-transparent white paint, the artist is not completely erasing them but intends to temporarily shift the viewer’s focus and force us to see the previously deprioritized black figure, in order to reveal what has been understated, suppressed, or ignored. Kaphar is asking the viewer to consider the symbolic purpose of including a black figure in the original painting, one who is clearly not a primary character in the story being told.

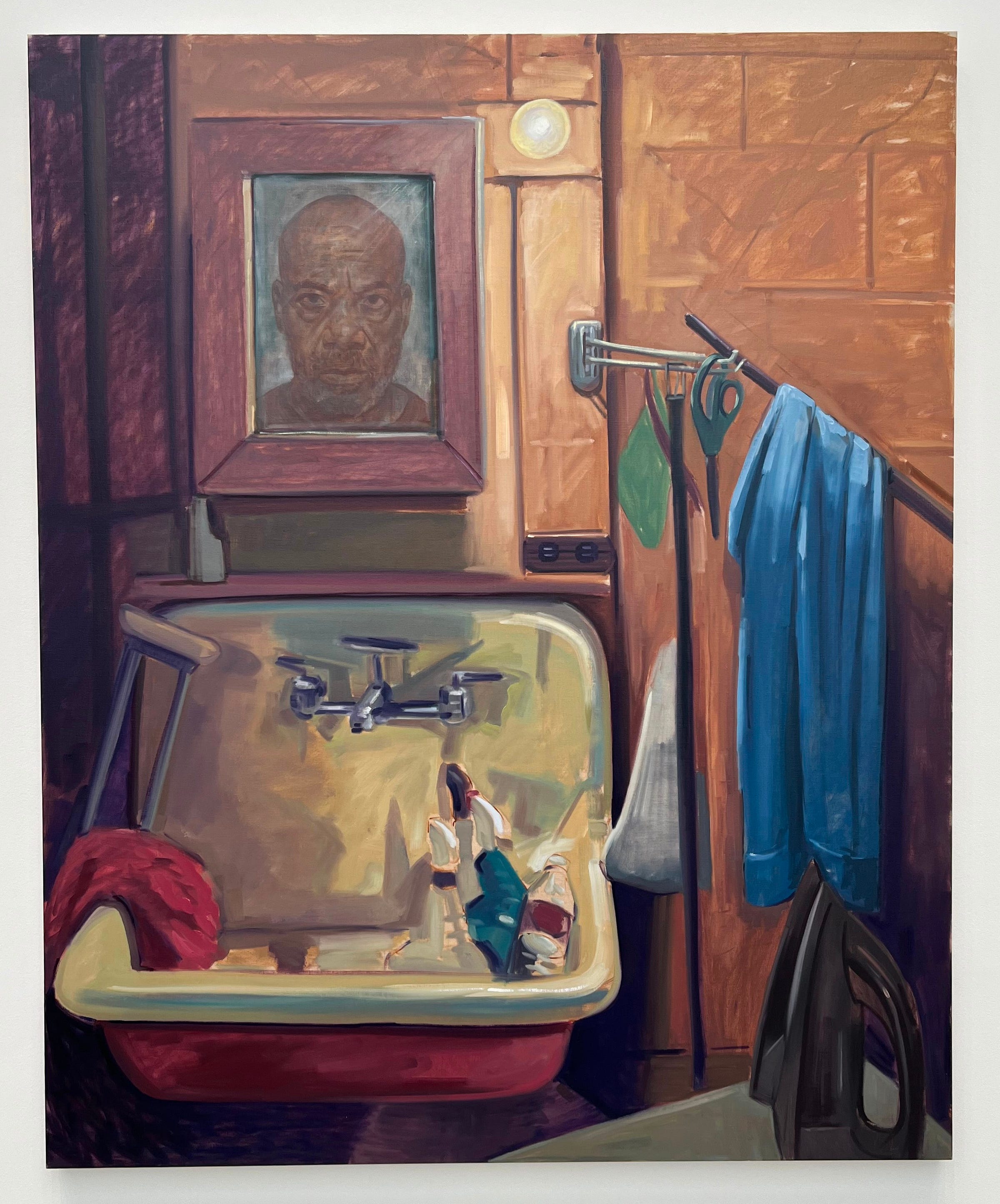

Kaphar’s artwork has always been intensely personal. Even his amended history paintings are fundamentally about his relationship with the subject, situation, or narrative being depicted. However, as his career progressed, the artist shifted his focus to confront contemporary issues and explore his personal family history with the same objective – not to erase or forget, but to amend the story and better understand how it relates to the present and impacts the future. Kaphar recognizes that present narratives about black life in America and even his own memory are subject to fictionalized depictions which prioritize some things and suppress or ignore others. For The Jerome Project, the artist initially set out to find his father’s first mugshot, which he did, but he also found the arrest photos of 97 other men with the same first and last name as his father. For each of the 97 men he created a portrait in oil and gold leaf, resembling a religious icon. Once complete, each panel was then submerged in liquid tar to a depth proportional to the amount of their life spent in prison, representing the time that person was hidden from view by society.

In the absence of adequate facts, our hearts rifle through memories, forging satisfactory fictions. – Titus Kaphar

Kaphar’s most recent series of paintings, Exhibiting Forgiveness, takes a semi-autobiographical turn relating to the film by the same name. The project began when Kaphar sat down to write a letter to his sons explaining his relationship with their absent grandfather. The exercise grew into a screenplay which he wrote while also working in his studio on the paintings which were then featured in the film and are now on exhibit at Gagosian. In the film, the main character is an artist who is beginning to gain recognition and success, raising his own two sons, but is confronted by an unexpected and unwelcome attempt at reconciliation by his estranged father.

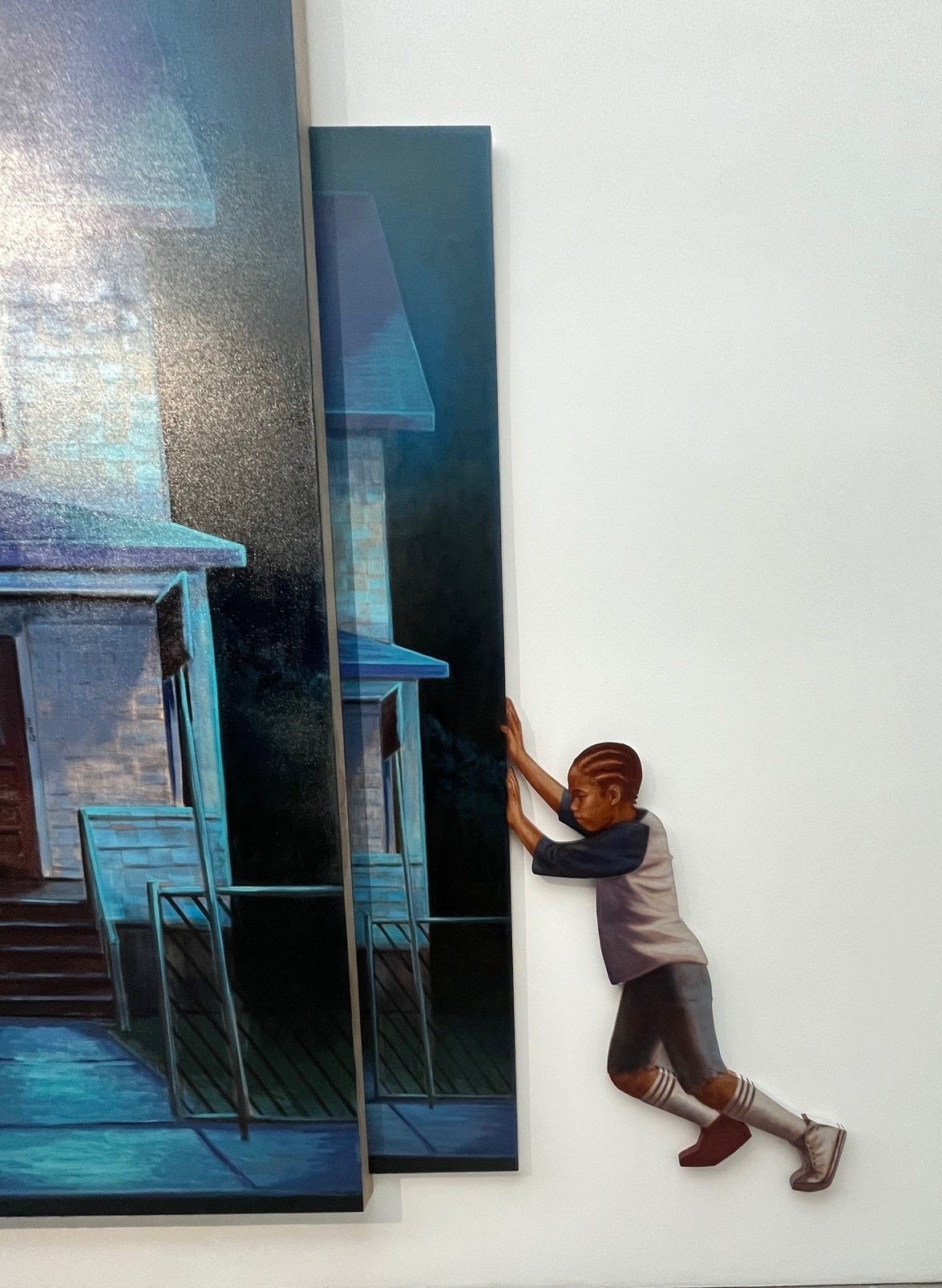

As in historical paintings, everything included by the artist serves a symbolic purpose. The excised figure of a boy pushing a lawnmower uphill in I hear you in my head depicts an event in Kaphar’s film Exhibiting Forgiveness in which the film’s protagonist, as a child, is injured by stepping on a nail while mowing. The excision from the painting represents the artist’s attempt to separate the boy he was from the pain of the event in his memory. Kaphar then placed the removed canvas on a chair displayed in the adjacent gallery as if to give the boy the opportunity to rest and recover. Throughout the remaining paintings in the exhibition, the young man has one blood red shoe and one white, representing how the trauma of this event was carried forward as part of his character.

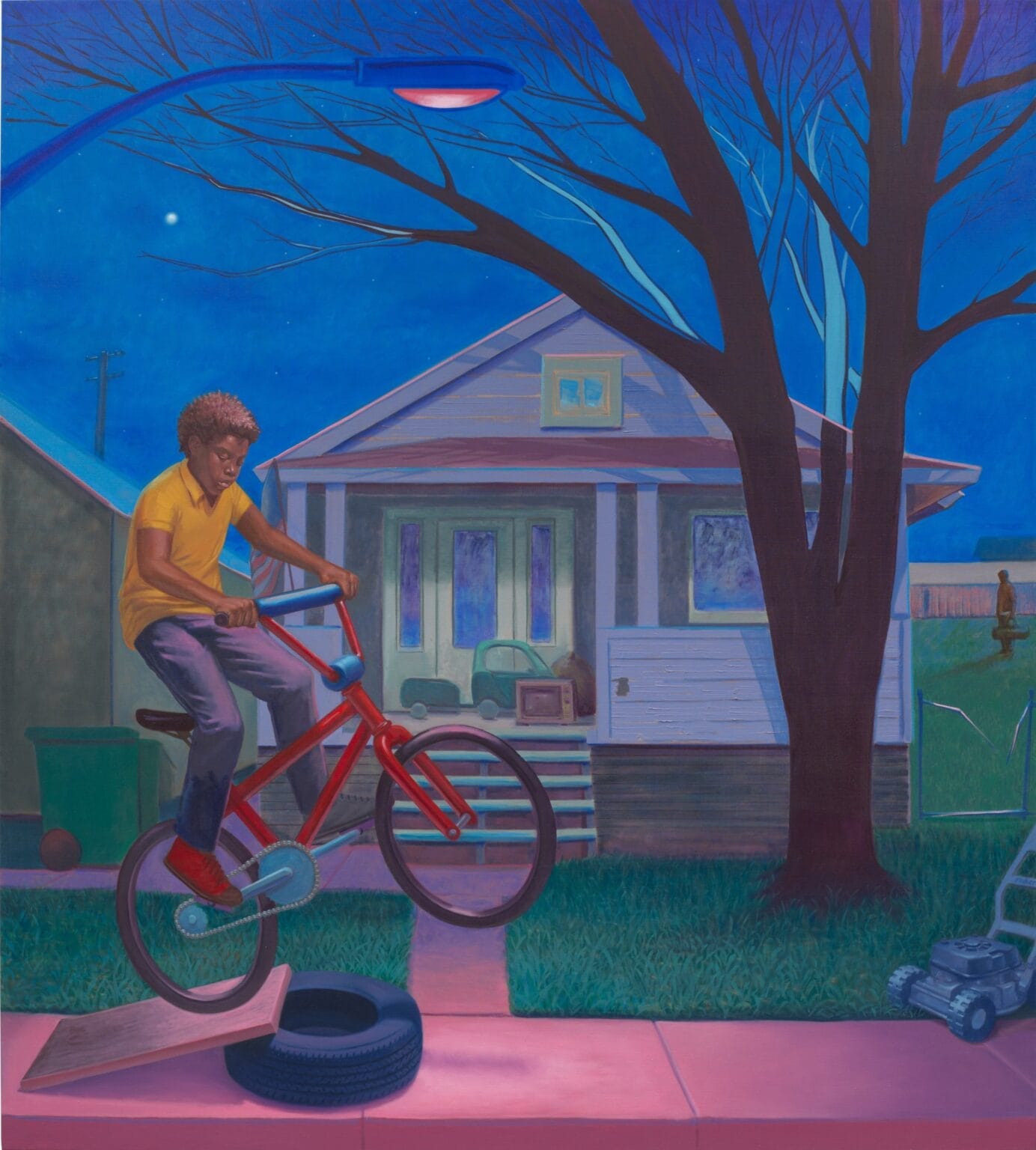

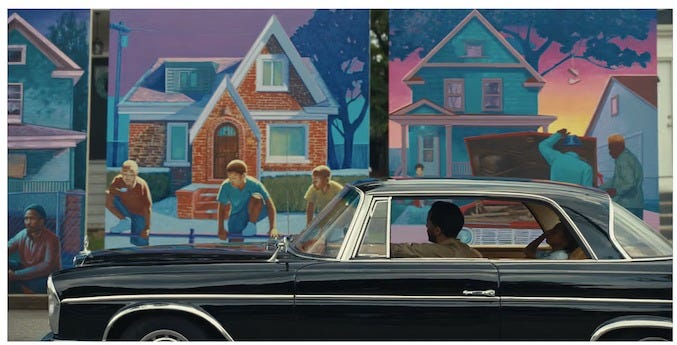

In one series of five very large canvases, the artist depicts a street scene. Although each painting is a stand-alone image, when hung together on a single wall in the gallery, the five paintings serve as a complete neighborhood. Each individual painting shows a different house as seen from the street and a different tableau of characters in front of that house, including the artist as a young man riding his bike over a homemade ramp under a streetlamp and sitting observing two older men working on a car in the driveway. At the far end of the series, the boy is depicted pushing one canvas behind the other as if closing up the street at the end of the day or putting away his memory of it.

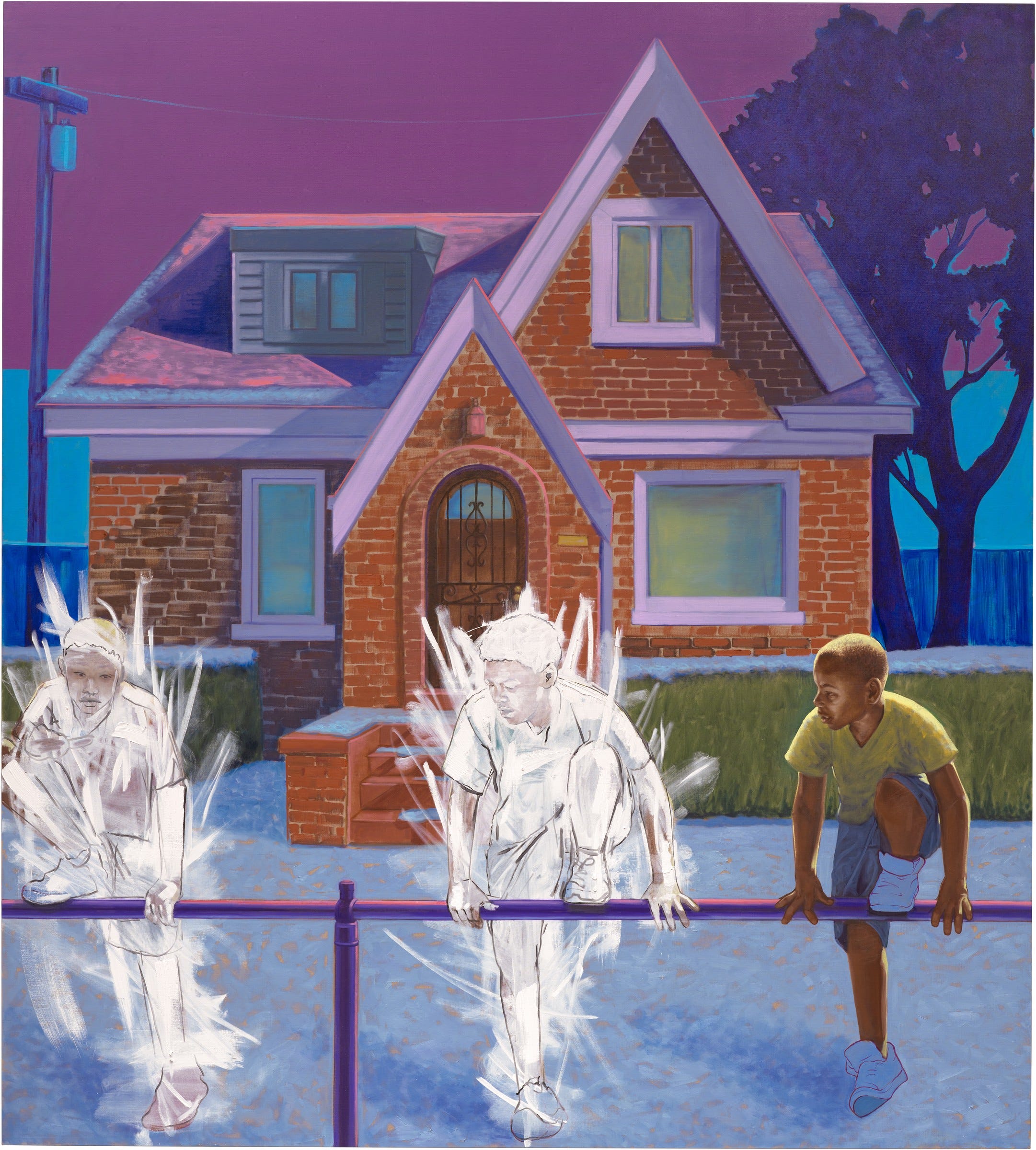

One of the most striking canvases in the series, So vulnerable, shows three boys balancing on a fence rail. As in Kaphar’s amended history paintings, two of the figures are painted over in semi-transparent white paint while the remaining figure looks over at his missing associates, the boy’s cousins, one of whom died while the other is in prison. In this instance, the white paint symbolizes the absence of his cousins from his adult life and his struggle to remember them as they were in a more idyllic memory of childhood innocence. The pre-trauma innocence of this memory is emphasized by the presence of two white shoes rather than one blood soaked and one white shoe as seen in the other panels.

The art on display in the exhibition at Gagosian is engaging, emotional, and highly personal. The narrative of childhood trauma and complicated family relationships is easily understood without having seen the film; however, much of the symbolism and detail incorporated into the paintings might be missed. In Kaphar’s approach to American history the artist seeks to amend history but without erasing the past, in order to improve our perception of the present and gain a clearer view of the future. Similarly, in both the film and the exhibition, Kaphar wants viewers to consider how the faultiness of memory impacts our interpretation of past personal events and the choices we make in the present, so that when presented with more facts or previously hidden details, we can amend our memories. In doing so we change our understanding of both past and present so that we can choose a different future direction. In this way, we gain clarity that allows us to exhibit forgiveness but without forgetting.

The exhibition at Gagosian ends November 2, 2024. https://gagosian.com/exhibitions/2024/titus-kaphar-exhibiting-forgiveness/

The film is currently in theaters in wide-release. Exhibiting Forgiveness | Official Trailer | Only In Theaters October 18

Thank you! Great to see more of his work. I was familiar with the gold leaf pieces only. Really powerful narratives.