One of the art historical anniversaries being celebrated this year is the centenary of the German artistic movement known as Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity; exhibitions are currently being held at Kunsthalle Mannheim in Germany and at the Neue Galerie in New York City. (see below) New Objectivity was a short-lived movement, based mostly in Germany in the 1920s during the Weimar Republic ruled by Germany’s first constitutional republic. The majority of New Objectivity artists were declared degenerate by the Nazi government that disbanded the republic when it came to power in 1933.

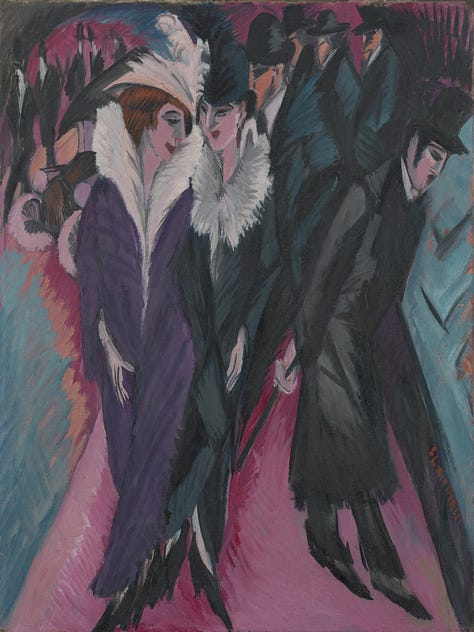

It’s fitting that Kunsthalle Mannheim is celebrating this anniversary because Neue Sachlichkeit was first identified by the director of that museum in 1925. Gustav F. Hartlaub put together an exhibition of contemporary German painting which he titled Die Neue Sachlichkeit: Deutsche Malerei seit de Expressionismus (The New Objectivity: German Painting Since Expressionism). The exhibition took note of a marked change in German art in the aftermath of World War One. The dominant style before and during the war had been Expressionism, as exemplified by the art of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1888-1930), Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), and Franz Marc (1880-1916).

Expressionist artists transformed their experiences of the world with individuality, painterly form, and emotionalism. That approach was rejected by the artists exhibited in Mannheim in 1925, including Christian Schad (German, 1894-1982). Schad’s portrait of Count St. Genois d'Anneaucourt is reproduced above. In this portrait, three fashionable figures from Viennese high society are posed in front of a shadowy cityscape that suggests the famously decadent 1920s nightlife in Paris, Berlin, or Vienna. The male figure is a Hungarian count; he’s accompanied by a baroness (left) and a famous Berlin transvestite. The sheer dresses are characteristic of the daring fashions worn in the cabarets and night clubs of Europe at the time. Schad traveled extensively in Germany, Italy, and Austria and like many New Objectivity artists, was inspired by older European art traditions, especially the smooth finishes and clarity of form found in Renaissance art. That inspiration can be seen in the detached quality Schad created with precise linear form and even lighting. At the same time, the artist managed to convey psychological tension with the poses and facial expressions.

Schad’s work straddles the line between a stylistic division within New Objectivity, one which was identified by Hartlaub in his original exhibition. One group was the Classicists, who, according to Hartlaub, were seeking to create a timeless image while accurately capturing visual reality. Schad’s portrait can be said to fit this definition, but his work also shows characteristics of the other group, the Verists, many of whom were Schad’s friends. The Verists were interested in recording, and in many cases satirizing, the social hypocrisy and moral decadence of the 1920s. Schad’s subjects in this painting certainly were participants in that decadence, but his works lacks the searing criticism and caricatures that are found in the work of the best known New Objectivity artists, Otto Dix and George Grosz.

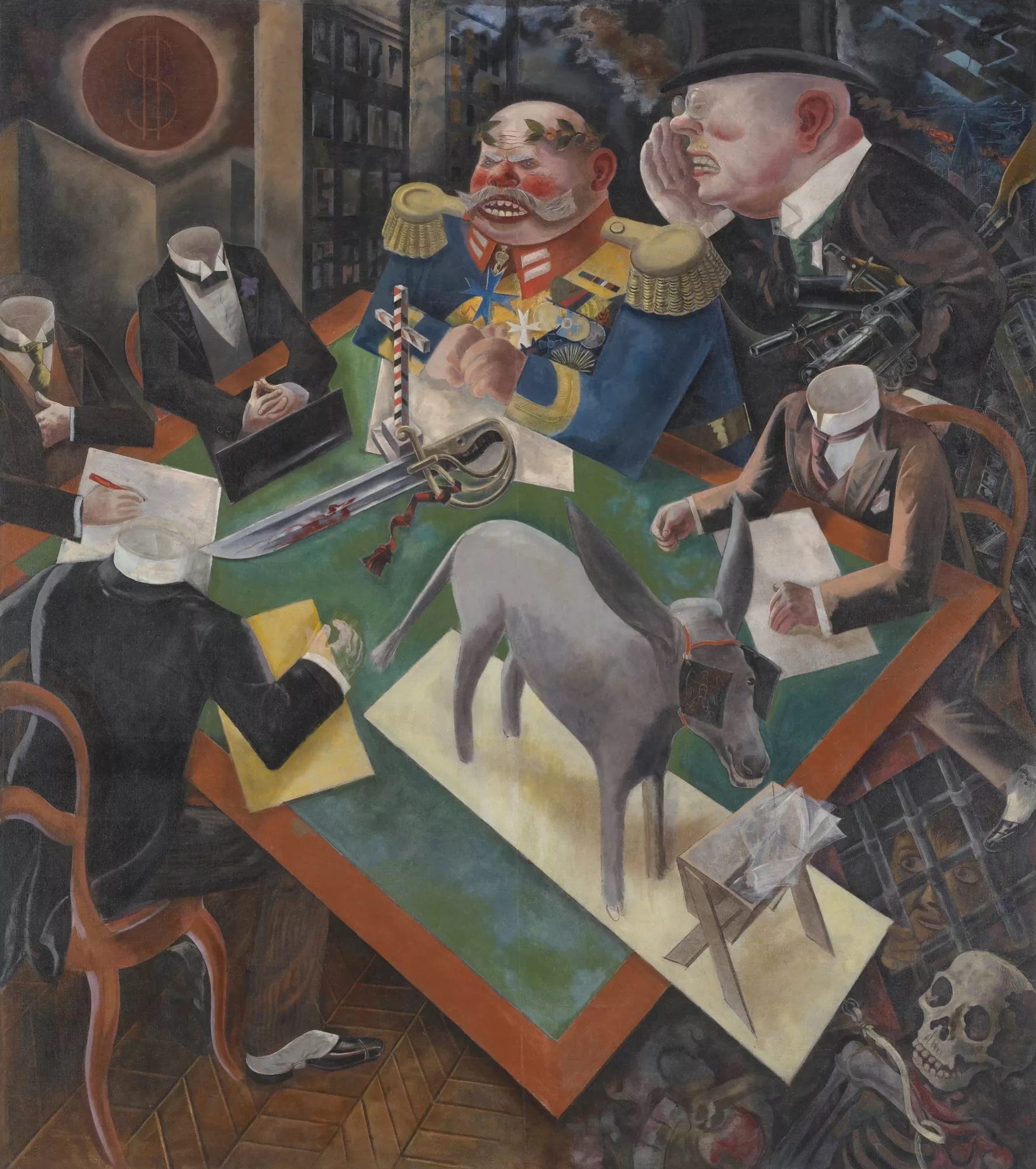

George Grosz (German-American, 1893-1959) was the person who coined the term “Verist” for his work and that of others who used figural art to critique German society. From an early age, the artist was fascinated by the world beyond Germany. The artist changed his name from Georg Groß to the more anglicized George Grosz, as a protest against widespread nationalism in Germany and to connect himself to international culture. Eclipse of the Sun is a large painting in which the artist expresses his distress over the political and economic powers at work in Weimar Germany. Painted in 1927, Grosz depicts the military and political leader Paul von Hindenburg in uniform with a bloody sword on the table before him. The other figures around the table are literally empty suits representing unthinking bureaucrats. An industrialist, carrying a train, weapons, and other products, whispers in Hindenburg’s ear while outside the window, the sun is eclipsed by greed in the form of the American dollar. Below the floor to the right can be seen a waiting skeleton and a caged youth. These may represent the likely results of the deals being made, death and the abandonment of hope for the future. The blinkered donkey represents the bourgeoisie which chooses to ignore the horrors around them as long as they are comfortable. The space is awkward and crowded and the figures are caricatures, typical of Grosz’s work in this period.

I drew and painted out of a spirit of contradiction, trying in my works to convince the world that it was ugly, sick and mendacious. – George Grosz, 1925

Grosz had several run-ins with the law over his works. In 1920, he was fined for insulting the army in an album of prints satirizing German society. In 1928, he was charged with blasphemy and sacrilege for a work critiquing the role of the clergy in nationalistic militarism. The artist was bitterly opposed to the National Socialist Party (Nazis). In 1932, Grosz accepted an offer to teach at the Art Students League in New York City. Though he returned briefly to Germany, he stayed only to resolve his affairs and collect his family. They docked in the U.S. one week before Hitler took power in 1933. Grosz became an American citizen in 1938 and was active as teacher and artist in New York for the rest of his life. Eclipse of the Sun is a featured painting in the current exhibition at the Neue Galerie.

Like Schad’s and Grosz’s, Georg Scholz’s (German, 1890-1945) works were included in the seminal exhibition in Mannheim. His early works were influenced by Cubism and Futurism, but after his service in World War One, the artist joined the Communist party and created Verist works that were critical of German post-war society. Of Things to Come uses satirical portraits of real figures as stand-ins for broader groups controlling Germany’s industrial and political climate. The title is taken from a book by the figure in the dark suit, Walther Rathenau, the foreign minister. He is flanked on the left by an American who was involved in securing the loans that helped stabilize Germany’s economy in the mid-1920s and on the right by a prominent German businessman. These two figures represent the ways in which foreigners and capitalism were enmeshed in the Weimar Republic’s political and economic situation. Though portraits, the figures are also symbols of their respective groups and Scholz displays them on an illusionistic pavement against a distant backdrop of factories, like characters in a play. Like so many avant garde artists in Germany in the 1930s, Scholz lost his teaching job and was declared a “degenerate” artist when the Nazis came to power. He was one of the artists whose works so offended the Nazis that he was forbidden to paint.

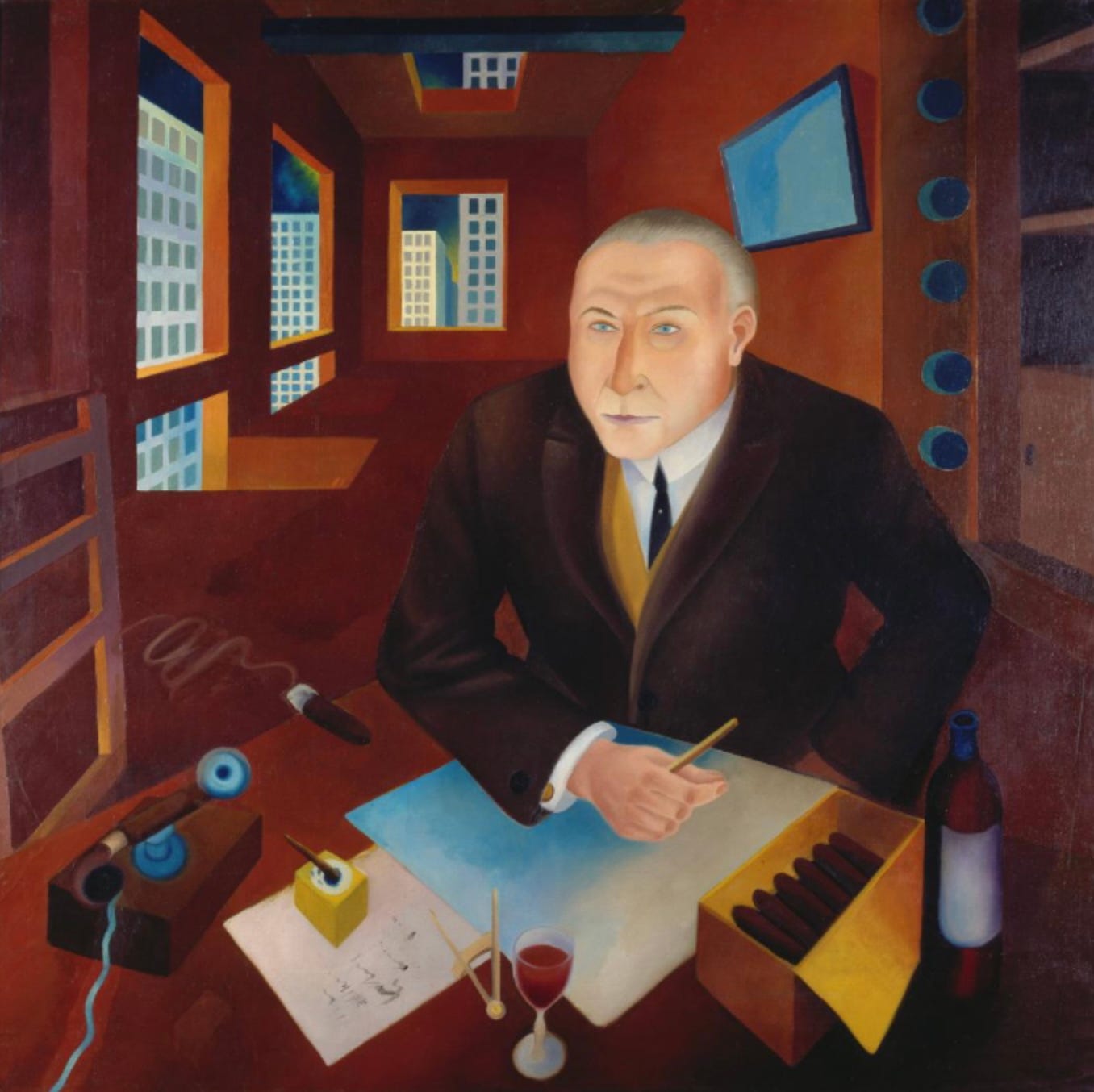

Heinrich Maria Davringhausen (German, 1894-1970) is a representative of the Classicist group within New Objectivity. He was trained as a sculptor but worked primarily in painting, at which he was self-taught. Like most artists who considered themselves avant garde and politically leftist, Davringhausen joined the Novembergruppe (November Group), an artist’s association formed in 1918 to advocate for a greater role in the education of artists and in the management of state arts organizations. The artist’s The Black Marketeer (Der Schieber) is as pointedly critical as Davringhausen ever got. Instead of caricature, he has depicted a smooth and pleasant-looking man at a desk. The true nature of the man is revealed by his surroundings, such as the office, represented using an exaggerated form of linear perspective which creates a sense that the walls are closing in on the figure and the featureless, many-windowed buildings (which look like skyscrapers before such structures existed) visible through the office windows. This setting suggests the businessman’s isolation from the world of ordinary people. The items on his desk indicate his wealth (wine and cigars) and the source of that wealth, papers and a phone, rather than useful products. Approximately 200 of Davringhausen’s works were removed from German museums and declared degenerate by the Nazis, more for the artist’s politics than for his style or subject matter. He went into exile in 1933, first to Spain, and then France where he remained until his death.

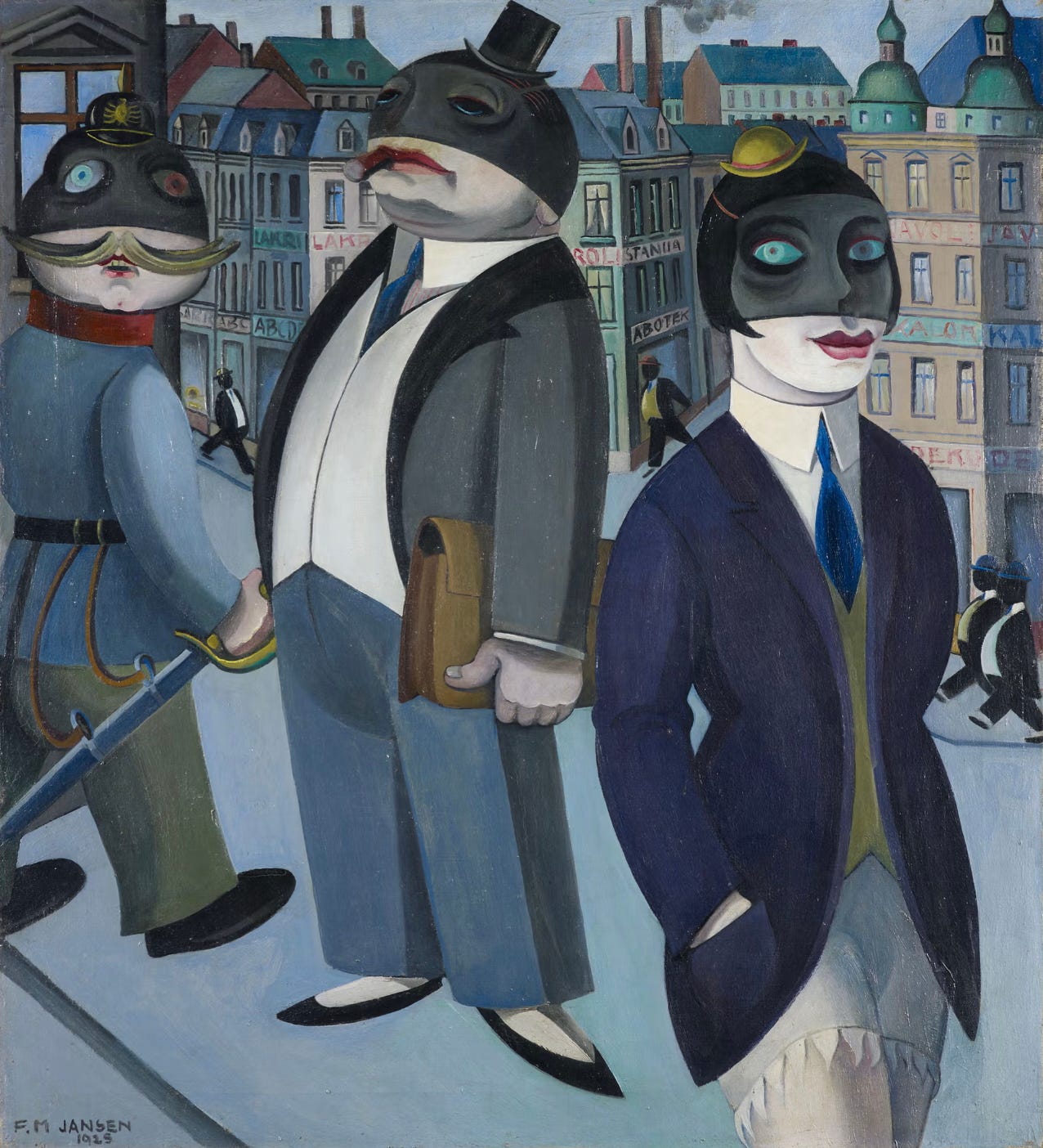

Unlike many of his colleagues in New Objectivity, Franz Maria Jansen (German, 1885-1958) chose to conform to the demands of the Nazis when they came to power, in spite of his works being confiscated and labeled degenerate. After the end of WW2, the artist helped reestablish the Berlin art community. Before the war, he was a successful printmaker and painter who participated in numerous international exhibitions and he was active in avant garde groups like the Secession in Cologne and Berlin. Though his early work was influenced by Art Nouveau and Symbolism, after being exposed to the work of René Magritte, Jansen’s style shifted to the New Objectivity Classicist approach that is sometimes called Magic Realism. This term, also coined in 1925, is variously applied to some Surrealist artists, to Classicist artists, and to others who stressed the uncanny and strange within a largely naturalistic style. Jansen had written a manifesto in 1918 denouncing the use of labels within the art world, calling on all artists, whatever their style, to address society and politics in their art. Masks shows three figures who represent 1920s types: the Soldier, the Businessman, and the New Woman. Beyond them, black-suited figures stride through a cartoonish city. The titular masks worn by the three figures suggest that the identities we see aren’t authentic, but the artist doesn’t indicate what the unmasked figures might reveal.

No women artists were included in the 1925 New Objectivity exhibition though there were quite a few working in styles similar to their male colleagues. This absence is one thing that both current exhibitions have tried to redress. Lotte Laserstein (German-Swedish, 1898-1994) was among the first women to be permitted to study at the Prussian Academy of Arts and took full advantage of her opportunity by advancing to “star pupil” status which gave her access to a her own studio and free models. The works she produced between her graduation in 1927 and her flight from Nazi persecution in 1933 are considered her best and representative of New Objectivity. Laserstein’s preferred subjects were women and the communities that they created for themselves with the larger society. The work above, Im Gasthaus (At the Inn), captures a young woman seated alone at a table, while behind her, a child reads a book and a barkeeper fills glasses for a waiter. The woman’s short hair and tailored clothes identify her as one of the New Women whose presence in German cities was often noted by painters, photographers and filmmakers of the era. The New Woman was a feminist ideal that had begun to appear in art, literature, and society in the late 19th century. This movement’s goal was increased access to education, expanded career choices, and freedom of movement within society. In post-WW1 Germany, women were forced to take on more public roles in the aftermath of war deaths and casualties, but many embraced the opportunities and adopted New Woman characteristics like short hair and tailored clothing. For many women, the movement also offered greater social and sexual freedom. Laserstein herself was a New Woman and depicted many such figures in her art. Laserstein left Germany for Sweden in 1933 and continued her career as a painter there.

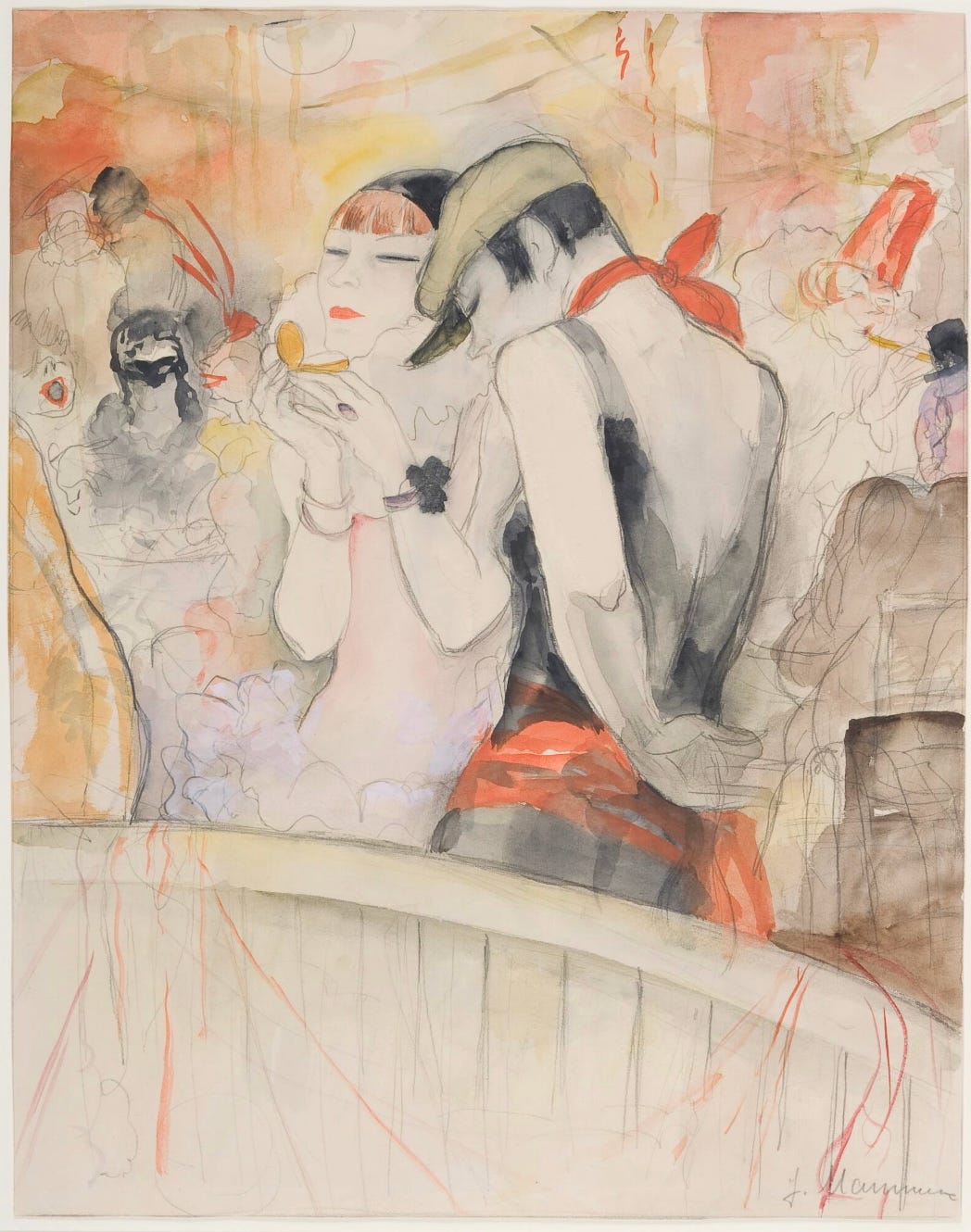

Jeanne Mammen (German, 1890-1976) was born in Germany but was raised in Paris where the opportunities for young women artists were greater. Returning to Germany in 1916, she faced a period of economic hardship which brought her into contact with a wide cross-section of Berlin society. This gave her great sympathy for all types of people. Eventually Mammen was able to make a living as an illustrator and creator of fashion plates. For both her illustration work and for her painting, the artist worked among all types of people. Women, from socialites to prostitutes, were her favorite subjects.

I always wished to be just a pair of eyes, to explore the world without being seen, only to see others. – Jeanne Mammen

Carnival is one of a series of drawings Mammen created capturing crowds interacting during a public festival. Two women are the focus of this composition, though other figures can be picked out around them, a chubby man in a bowler hat and a red-hatted figure with a noise-maker on the right and masked and laughing figures at left. Within the central pair, one dressed in pink refreshes her makeup while the other, in black and wearing a cap, seems to wait for her companion’s attention. It is hard to say whether Mammen intended us to read these figures as lesbians, but the work was made at the same time that she was illustrating a collection of lesbian love poems. In 1933, after Mammen’s work appeared in an exhibition featuring Berlin’s women artists, the Nazis denounced her art and her refusal to depict properly submissive women. Until the end of the war she practiced “inner emigration,” a form of personal protest which, in Mammen’s case, involved refraining from displaying her art or working for Nazi-accepted publications. In private, the artist began to experiment with Cubism and Expressionism and to translate the poetry of Symbolist Arthur Rimbaud. Neither activity would have been approved, but her secret rebellion was never uncovered. After the war, Mammen expanded her artistic practice to assemblage sculpture, collage, and set design. Like many women artists of her era, Jeanne Mammen was nearly forgotten after her death. With the rise of feminist art history in the 1990s, her works and those of many others were brought out of the shadows for everyone to discover.

I close with one of the best known New Objectivity artists, Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969). Like George Grosz, Dix was a Verist, known for his paintings capturing the dark side of German society, especially the wounded veterans of World War One. The artist had served in that war and was deeply affected by his experiences, suffering from nightmares for years. The work I have chosen to include is not one of Dix’s scenes of war-ravaged men; instead I was interested to discover one of the New Women seen through a male artist’s eyes. Reclining Woman on a Leopard Skin depicts a woman with short red hair lying on the titular skin and an orange-red cloth. Beyond the bed can be seen a snarling beast, perhaps a dog, but one which looks both feral and vicious. The title’s “reclining woman” hardly fits the art historical tradition of sensual, inviting women spread across the foregrounds of paintings from Titian to Édouard Manet. Dix’s woman has twisted her body and raised herself up on her arms as she leans toward the viewer. The snarling animal combines with the woman’s red lips and staring green eyes to make her seem predatory, a term frequently used in conservative critiques of the New Woman movement. The dark and tense atmosphere of this painting place it squarely within New Objectivity’s practice of critical realism.

Even before the Nazis had completely seized power, they had identified Otto Dix as a degenerate artist. Two of his most famous paintings, The Trench and War Cripples, eventually ended up in the infamous Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition of 1937. Both works were destroyed in the aftermath of that exhibition. Many works from the 1925 New Objectivity exhibition also disappeared during World War 2, either lost in the chaos of war or deliberately destroyed by the Nazis.

New Objectivity was characterized by social commentary, satirical critique, and detailed renderings of life in 1920s Germany. While the Classicists joined in the pan-European Return to Order, rejecting the abstraction and distorted forms of earlier decades, the Verists turned their unblinking gaze on the problems they saw afflicting their society. Their works record a volatile time in German history, one which was consumed by the Nazi dictatorship. Though most of the era’s artists and many of their works suffered as a result, much survived to share that era with today’s viewers.

We’ll be back soon with more art. Thank you for subscribing and reading. Please comment, like, or share.

Current exhibitions:

The New Objectivity: A Centennial, Kunsthalle Mannheim, Friedrichsplatz 4, 68165 Mannheim, Germany. Through March 9, 2025. https://www.kuma.art/en/exhibitions/new-objectivity

Neue Sachlichkeit / New Objectivity, Neue Galerie, 1048 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York, USA. Through May 26, 2025. https://www.neuegalerie.org/exhibitions/neuesachlichkeit

I am pleased to report that we saw the New Objectivity exhibit at the Neue Gallerie today. WOW! A note to anyone who can get to it: take a notepad. They don't allow photographs (which given the space, makes sense), so for those whose usual mode is to take a quick photograph as a note, you can't do that here. This exhibit pulled together many pieces that would not be seen in NYC outside this exhibit, and they're not easy to find online. A couple that appealed to me, particularly, were Curt Querner's The Sower and another, artist's name I don't recall, Drunkard at a Bar. Just an astonishing, thrilling exhibit. Ironically, and not for the first time, it was your post that alerted me to it--even though I am right here in NYC! Thank you!

Your commentary here is, as always, richly informative. The power of this art is extraordinary—and eerily relevant to the present moment. Your choice of paintings to show the work of each artist depicted is superb—no surprise, coming from you. I was delighted to see the Laserstein. Only recently did I become aware of her work, and this painting is a particular favorite. We must all be grateful to those who made it their business to lift up these brilliant female artistic voices. I am hopeful I WILL get to the Neue Galerie exhibit. Knock wood!