Chance Encounters, Edition 57

Suchitra Mattai: Imagine A World

In her art, Suchitra Mattai (Guyanese-American, b. 1973) repurposes the fabrics and objects of her family’s history to illuminate the past and to imagine the future. The artist, currently the subject of an exhibition at the Seattle Asian Art Museum, is one of the many Contemporary artists working with craft and textile materials and techniques long regarded as unworthy of use in a fine art context. (see other examples in Viewing Room 37) She hopes that eventually these materials and techniques will be viewed as one option of many by all artists and not just woman-centered choices. Nevertheless, Mattai has chosen many of her materials to honor the women of her family, grandmothers, aunts, and her mother, who worked with embroidery, macramé, crochet, and sewing throughout their lives.

I learned all these practices like embroidery, sewing and crochet when I was young, and I would make things all the time, so it became natural – when I allowed myself to be more intuitive – to actually have those practices be a part of my overall artistic practice. – Suchitra Mattai

Discouraged by family from pursuing her dream of becoming a visual artist, Mattai completed a degree in statistics at Rutgers University before moving on to the University of Pennsylvania to work toward a PhD in South Asian Art, thinking that at least she could maintain contact with art as an academic. In her third year, she realized that she still wanted to be a maker of art, so she changed direction and completed an MFA in painting and drawing, as well as an MA in South Asian Art.

Castaways (2023), of which I have included both the complete work and a detail, is an excellent introduction to Mattai’s work. The first impression of the work is dominated by the section made of red, pink and gold vintage saris woven together into a dense surface and decorated with gold cord and tassels. A closer look reveals that the openings in this frame are filled with scenes of figures in a tropical landscape. The artist has used a found needlepoint image and reworked parts of it to highlight one figure in each vignette. The period clothing of the original needlework has been altered by the addition of embroidery floss stripes and each has been given a halo of colored lines emanating from their heads, mostly red on the left and mostly blue on the right.

The tropical theme of the found needlepoint links to Mattai’s family history in Guyana. When slavery was abolished in the former British colony of Guiana, the need for agricultural workers for the sugar cane and rice plantations was filled by nearly a quarter of a million indentured laborers from India. For decades, this form of forced labor was in use in British colonies in the Caribbean. Many Indo-Caribbean artists explore the legacy of cultural displacement and trauma they have inherited. In Castaways, Mattai mixes past and present through her intervention in the needlepoint and suggests the way we distance ourselves from history by placing the imagery behind the luxurious density of the woven sari border.

Though Mattai is best known for her woven sari works, some of which are made on a monumental scale, she works in many different media. In Through the Glass Darkly (2021), the decoration on a broken plate depicting an idealized 18th century landscape is expanded by the artist. Mattai frequently incorporates 19th century European decorative arts: furniture, architectural pieces, and as here, china, to symbolize the time period her ancestors were brought to South America. The plate is an example of Red Willow china produced in both Europe and North America. The broken plate, a found object like so many of the artist’s materials, signifies the rupture created in her ancestors’ live by their journey into bondage. At the same time, the expansion of the landscape beyond the plate suggests that there’s more to the story than the idealized excerpt on the original object.

The practice itself is dissecting and reimagining and retelling and reshaping myth and folklore and stories… -- Suchitra Mattai

Another example of incorporating a found object into the structure of her work is found in Mattai’s an echo, a dance, which consists of a carved architectural fragment at the top from which is suspended a combination of materials. The large area of dark metal objects is comprised of ghungroo bells which are used by classical Indian dancers. Strings of these bells are used as anklets by the dancers; the more skilled the dancer, the more bells they wear, sometimes as many as 200. The bells help to emphasize the rhythm of the dance. In Mattai’s work, they refer to this important tradition of Indian culture, one which was often banned by the British before India’s independence. Classical Indian dance has a more personal meaning for the artist too since her sister studies the art form. The dark mass of bells is interrupted by paths or streams of woven saris. These streams and the brightly-colored tassels and trim lighten the mood of this work considerably, and perhaps suggest the movements and costumes of a dancer.

For many descriptions of her works, Mattai carefully identifies the saris she has used as “worn.” This is important to the artist because she feels that the clothing one wears acquires not only the shape and scent of the wearer but a lasting connection to their life. Mattai sources her saris from family members, secondhand shops, and donations. She especially likes using family saris as this allows her to incorporate family stories into the histories embodied in her work. “Sari” means “strip of cloth” and the artist cuts the garments she uses into more workable strips. To create her works, she uses a grid of rope netting or wire into which she weaves the knotted strips of cloth. She plans her compositions beforehand using her training in both mathematics and art. a self-portrait combines many aspects of Mattai’s personal and family history. The mostly pink and red background is interrupted at times by areas of green that resemble branches growing from the central section of dried grass. At the very bottom are two patches of bright blue, like hints of the ocean. Mattai has noted that much of her early life was spent near the Atlantic Ocean – in Guyana, Nova Scotia, New Jersey, and New York City.

Another highly symbolic material in this work is the braided synthetic hair that hangs against the grass section. (The other dark braids are braided saris.) For Mattai, hair represents part of the ritual of being a South Asian woman and she has many memories of her hair being braided by her mother and other female relatives. The braid is also symbolic of bringing order to natural chaos. The found medallion hanging in the center has a scene of figures working in a field, perhaps cutting grass like the dried grass of this artwork. To me, the medallion and dried grass seem to refer to Mattai’s ancestors laboring in the sugar cane and rice fields. However, the idealized style of the medallion’s figures glosses over the hard work, as history frequently softens the edges of the past.

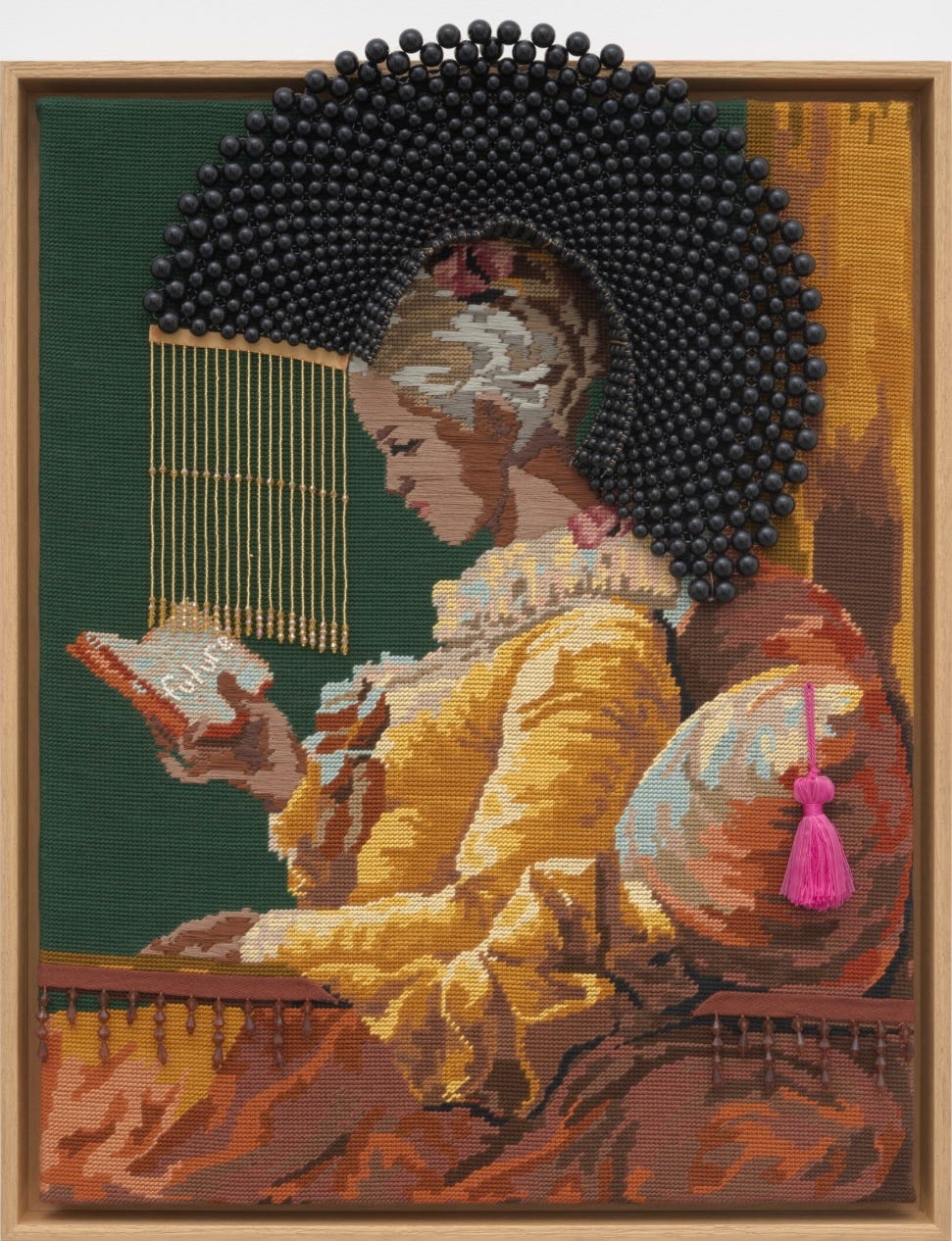

I first encountered Mattai’s work when I saw future perfect while wandering the internet. I was drawn to the work because, like Castaways, it uses a piece of found needlepoint, and a design with which I was familiar. I learned to needlepoint as a child and remember wishing for a very expensive kit that would allow me to execute the very image in future perfect. I was disappointed when my mother wouldn’t purchase the kit for me and my allowance was insufficient. The needlepoint is based on the Rococo painting Young Girl Reading by Jean Honoré Fragonard (French, 1732-1806), in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

Mattai has altered the original needlework by replacing pale skin tones with browner colors like her own skin. A bright pink tassel is added to the cushion at right and the artist has given the reader an ornate beaded headdress. Finally, across the open book is the word “future” in pearl beads. I was fascinated by the artist’s interventions and the connections to my own crafting history, but I didn’t really think more deeply about the meaning of the work until I began to prepare this essay.

I take that history, I use it to tell a different story; rupturing that history, creating space for a new story, to sit by its side. – Suchitra Mattai

future perfect is one of the works in which Mattai disrupts our understanding of the past and opens a space for us to imagine a future in which we will welcome everyone’s story in museums and history books.

The relationship between the ocean and people forcibly brought to labor in the Americas, including Mattai’s ancestors, is called to mind by The Sea Wall (2024). In traditional Hindu culture, to cross the ocean was to break with all the beliefs that were central to a believer’s identity, a separation from the homeland, from ancestry and caste and from the cycle of reincarnation. The pink wall in the foreground marks a clear separation between the land and the water and sky. The pink land is ornamented with colorful, patterned shapes, like miniature exotic buildings, and topped by banners made from saris and tassels. At the base of the opening in the wall a single figure looks across the flower-patterned ocean. From her position to the horizon, other heads adorned with halos of pink rays appear to float in the sea, individually and in groups, all with their faces turned from the pink land. Are these the people brought to labor in the plantations or their descendants, like Mattai’s family, who left their homes in search of greater opportunity? Whoever they might be, they signify diaspora – the separation of people from their homeland.

Though Mattai’s family moved from Guyana when she was just 3, the land and her family’s history there became familiar to her from the pictures she saw and the stories she heard. As a result she felt both part of her native land and alienated from it. Her family moved several times as she was growing up too, so she never felt a permanent connection to one place. As a result, the artist has often felt that she was creating images of an idealized home, an invented place where she would not feel like an outsider.

Through each puncture of embroidery, each woven thread, and each painted stroke, I am both bounded by and freed from my past, present, and future “homes.” – Suchitra Mattai

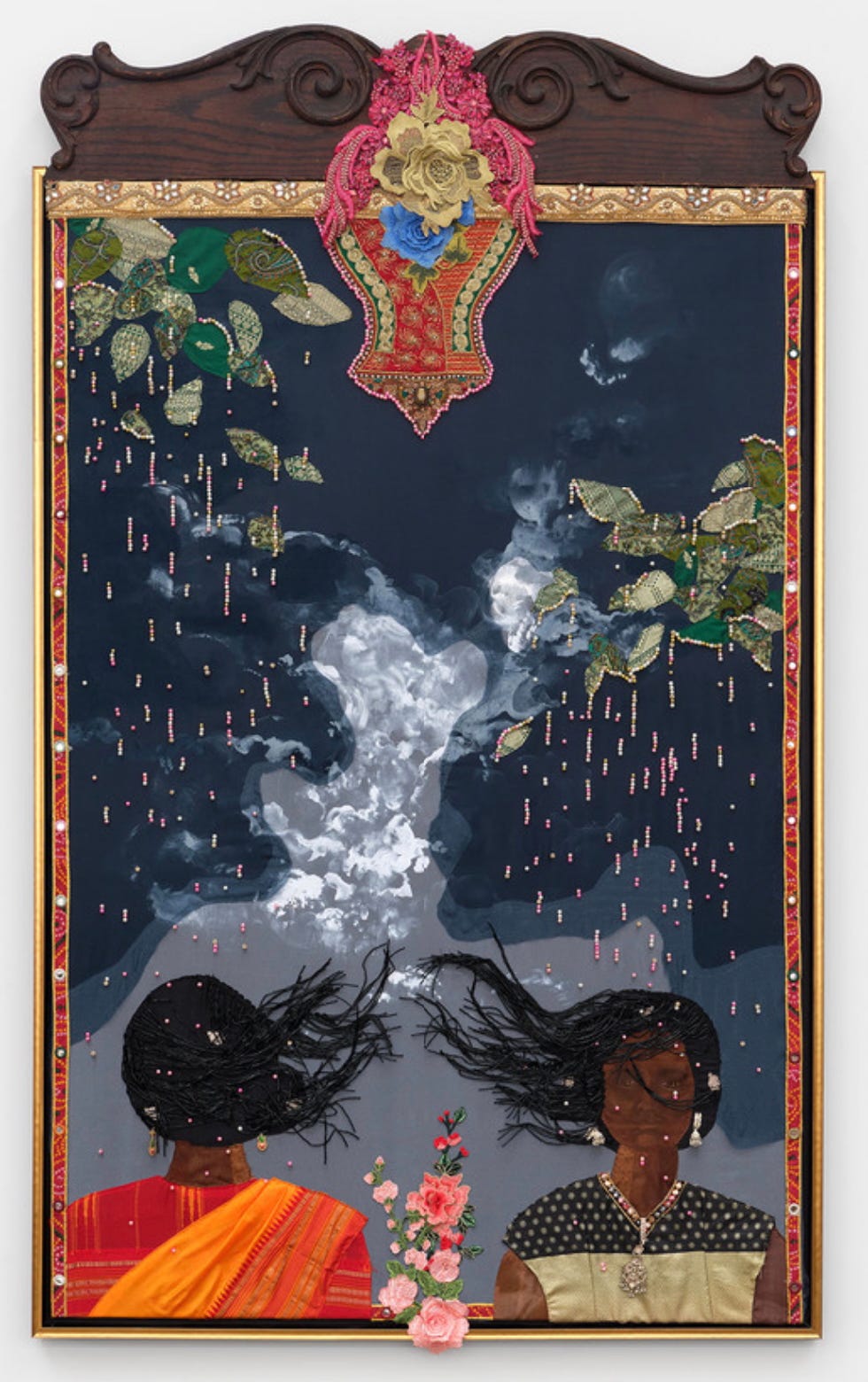

under the same rain reflects the artist’s sense of connection with other places and other people, both past and present. In a painted rainstorm, two figures stand beneath streaks of rain represented by colorful beads. At the left a figure in a sari faces away from the viewer while at the right a second figure, in a sleeveless blouse and glittering jewelry faces us. Each woman’s hair, made from strings of black beads, is tousled by the wind and blows toward the other, never quite touching. They seem to be two sides of the same history, past and present, far and near, different yet the same.

Mattai has also created sculptures incorporating her repurposed saris. In this example, braided saris cover an armature to create a life-size dancer in motion. The title evokes the sensory experience of witnessing the dance in reality. Like all of the artist’s works, this sculpture demonstrates the power of Mattai’s materials to seduce the viewer with their beauty and to create worlds of possibility.

In this video, the artist discusses her work in the context of her current exhibition at the Seattle Asian Art Museum.

Mattai’s art creates places that are familiar yet unfamiliar, mimicking the feelings she has experienced and using familiar domestic materials in new and often surprising ways. Her works are packed with color and texture, creating images while never losing the identifiable qualities of the original objects. Often focusing on forgotten and ignored stories, the artist explores how traditions can be reworked to make space for new ways of thinking about and relating to one another.

If we are going to find the utopian, equitable space that we all want to live in, that we dream of, we have to completely change what occupies the collective consciousness. In order to do so we need a brand-new cast of characters and stories, and a brand-new sense of mythology and folklore. – Suchitra Mattai

Current exhibitions

Suchitra Mattai: she walked in reverse and found their songs. Through July 20, 2025 at Seattle Asian Art Museum, 1400 East Prospect Street, Seattle Washington, USA, 98112. https://www.seattleartmuseum.org/whats-on/exhibitions/suchitra-mattai

Suchitra Mattai: The Fall. Through September 7, 2025 at The Joslyn Art Museum, 2200 Dodge Street, Omaha, Nebraska, USA, 68102. https://joslyn.org/exhibitions/suchitra-mattai/

Suchitra Mattai: with abundance we meet (site-specific installation) at Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, 1934 Poplar Avenue, Memphis, Tennessee, USA, 38104. https://www.brooksmuseum.org/exhibitions/suchitra-mattai-with-abundance-we-meet

Wired for Wonder, a multisensory maze, in collaboration with Getty’s PST ART: Art & Science Collide. Through August 1, 2025 at Kidspace Children’s Museum, 480 North Arroyo Boulevard, Pasadena, California, USA, 91103. https://kidspacemuseum.org/wired-for-wonder/

In addition to the exhibitions listed above, the artist will be included in the Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil, which opens on September 6, 2025.

Suchitra Mattai is represented by Roberts Projects, Los Angeles.

Thank you for reading and subscribing. Remember to like, comment, and share I Require Art. I’ll be back next week with more art and ideas to share.