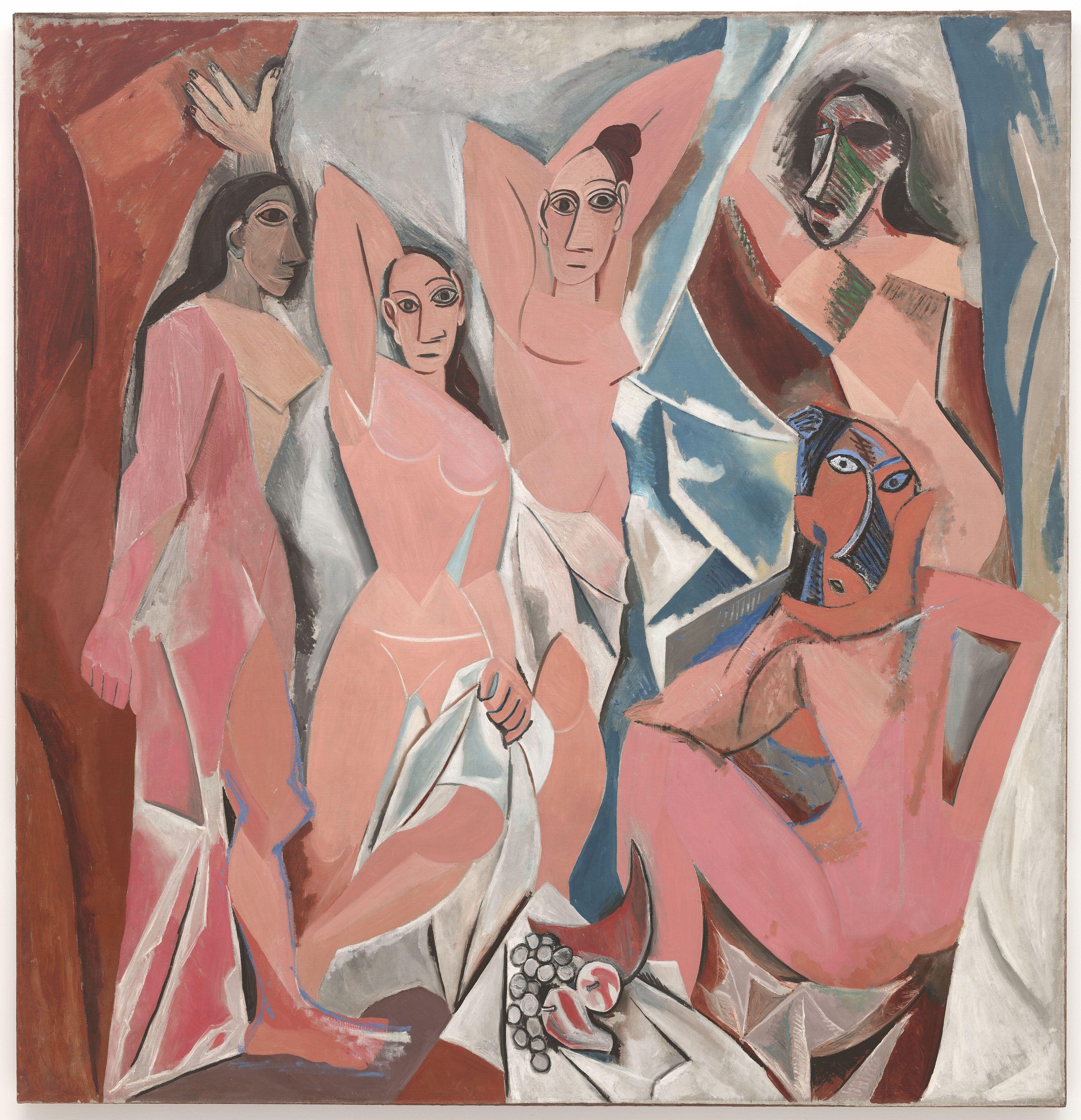

This is the second part of our series on Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973), in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the artist’s death. In the first part, I discussed Picasso’s early life and his first years as an artist including the Blue and Rose Periods. In this edition, I’m taking a look at Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (The Young Ladies of Avignon).

Completed in 1907, this large painting continues the Rose Period palette but takes a drastic and startling stylistic leap. Though sometimes referred to as the first Cubist painting, the work is best seen as a kind of proto-Cubist experiment. The fractured, often angular shapes would become familiar in Picasso’s and Georges Braque’s later Cubist works, but the more expressionist qualities, mask-like faces, and variable paint thickness, were not part of the style Picasso and Braque created together.

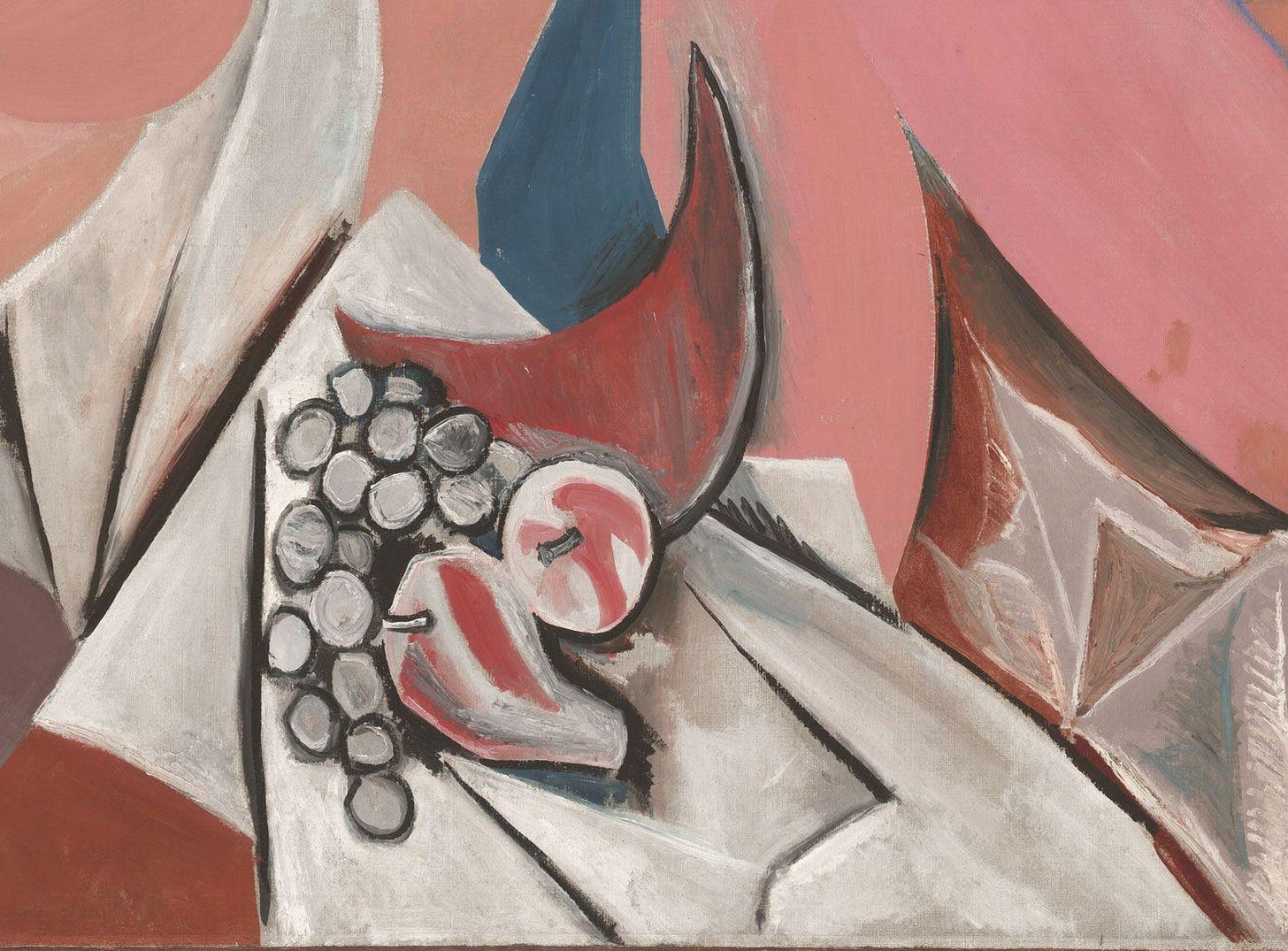

In its final form, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon depicts five nude women, divided into two groups, three to the left and two to the right, surrounded by red, white, and blue-gray curtains. In the center, near the lower edge of the painting is a small still life, grapes, an apple, a pear, and a wedge-shaped object, perhaps some melon, painted in neutral and deep red tones. By overlapping two of the figures, this still life is one of a very few sections of the composition that suggest anything approaching illusionistic depth. Most aspects of the composition show distortions of proportion and shape, with variations of color and value that suggest but do not actually describe naturalistic depth.

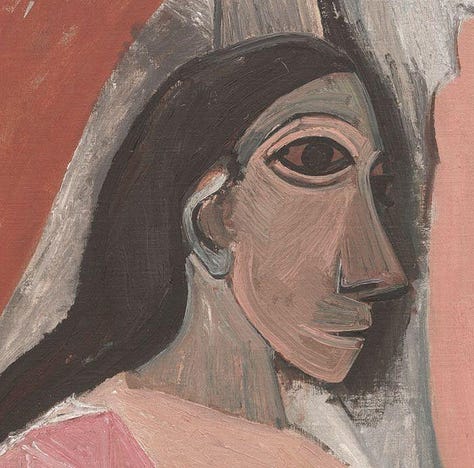

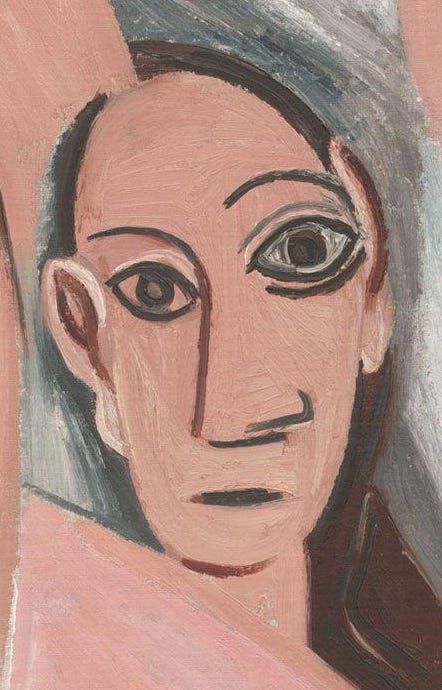

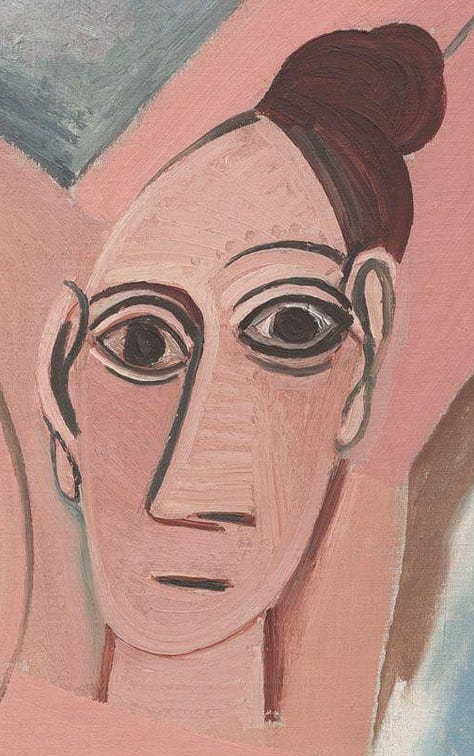

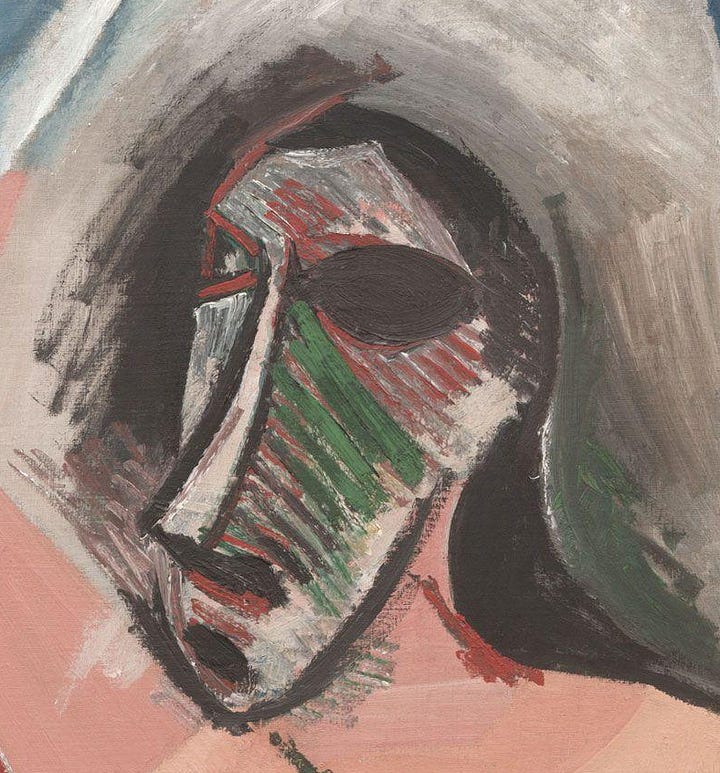

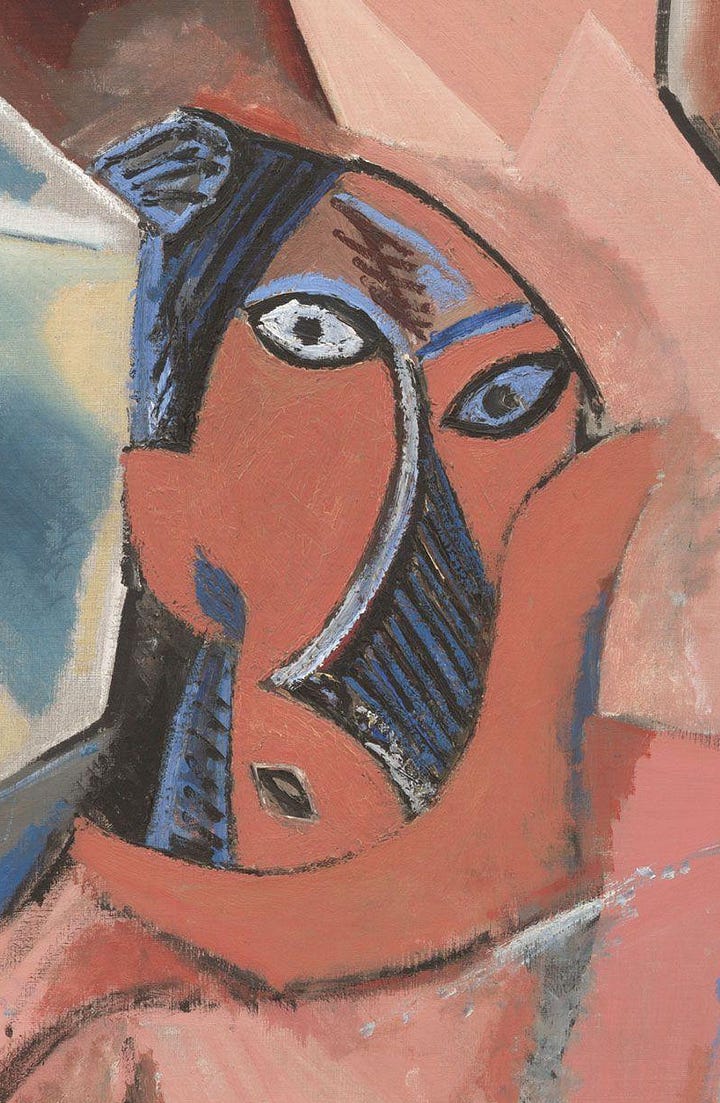

Most observers notice and comment on the dramatic and confrontational faces of the women in the painting. The central figure and the woman to her left face the viewer with large staring eyes. The leftmost figure has a brown profile head with a front-facing eye. The two women to the right have distorted, multi-colored, mask-like faces which are based on tribal masks. These faces also have prominent eyes directed toward the viewer, so one feels the weight of all of these staring eyes.

In 1907, when Picasso showed this painting to his friends and colleagues, they were shocked and dismayed. Henri Matisse, who Picasso had met at Gertrude Stein’s and with whom Picasso felt competitive, thought Les Demoiselles d’Avignon a joke, and a bad one at that. Georges Braque was one the many artists who saw the painting, and though he too disliked it, something in it spoke to him, eventually leading to the fruitful collaboration with Picasso that resulted in the Cubism movement.

In the face of the negative response his painting received, Picasso rolled the canvas and kept it in his studio until it was exhibited publicly at the Salon d’Antin in 1916. Though Picasso had chosen the name Le Bordel d’Avignon (The Avignon Bordello), the painting was exhibited with the less suggestive title it still carries. The Avignon of the title is not the French city but the name of a Barcelona street where brothels were located at the turn of the 20th century. Picasso never cared for this title and always referred to the painting by his original title or as mon bordel (my bordello). Whatever its name, the public reception of the painting, disgust and disapproval, was no better than that of his friends and colleagues and the painting returned to the studio again.

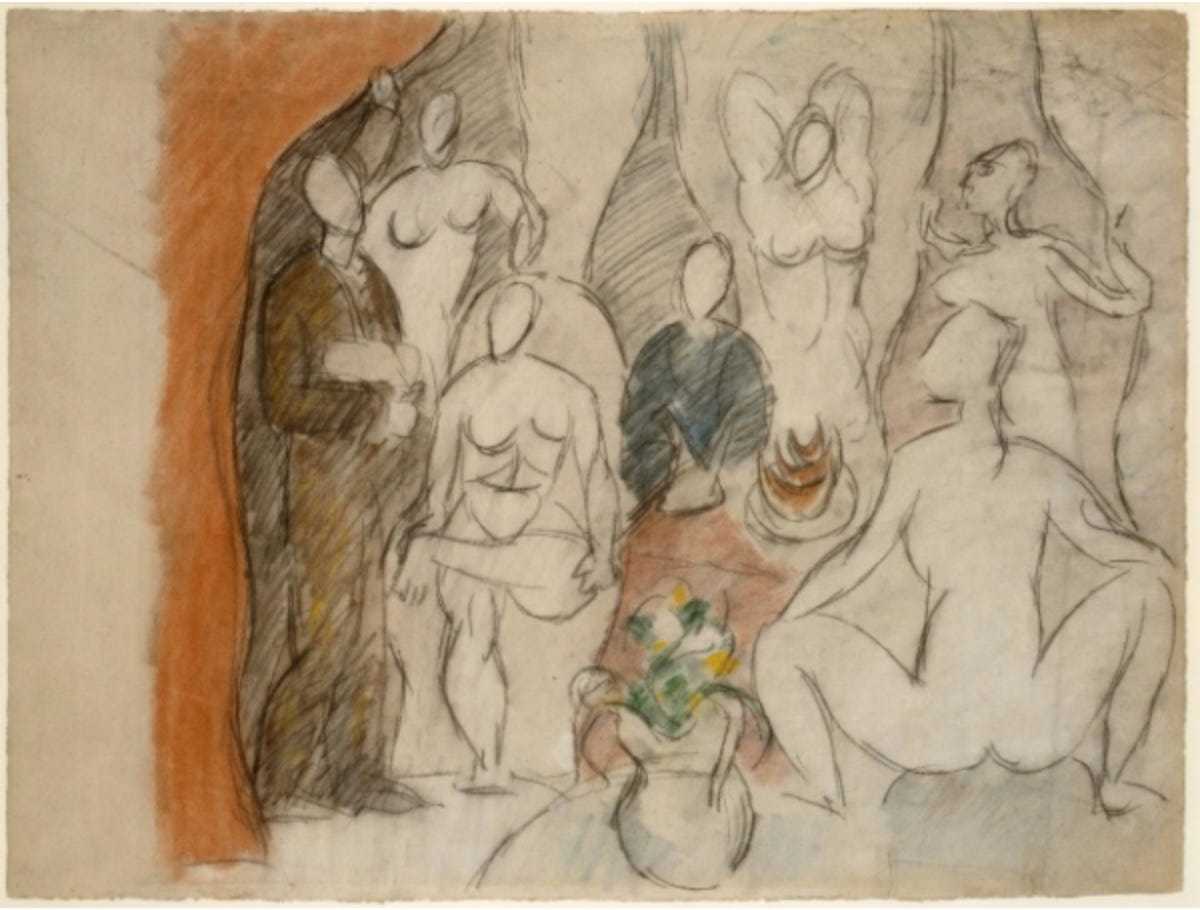

Some of Picasso’s studies for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon survive. The drawing above shows us that Picasso originally intended a more narrative approach by the inclusion of two male figures. In this study, the male figures are more finished than the women and we can see a vase with flowers and a plate of melon wedges. The earliest studies identify the men as a sailor and a medical student, the latter often cited by interpreters as evidence of Picasso’s fear of diseases associated with sex. If that was Picasso’s earliest intention, his removal of the male figures shifts the focus of the painting to the women and, like many of the artist’s choices in this work, complicates its meaning and discourages the viewer from settling for a simplistic or superficial interpretation.

There are several elements in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon that refer to earlier art. We know that after Pablo Picasso left his formal artistic training, he spent a lot of time in museums, studying and copying the works of earlier artists. The three women grouped on the left side of the composition bear comparison with one of the most commonly reused motifs of Classical Antiquity – the Three Graces. The Three Graces consist of a group of three standing women, with each seen from a different angle, perhaps one seen frontally or from behind, one in profile, and the third in the opposite profile.

The example above was painted by the important Flemish Baroque painter Peter Paul Rubens and was in the collection of the Prado Museum when Picasso was a student in Madrid around 1900. In Rubens’ painting, the women are flanked on the left by curtains hanging from a tree. The women themselves are linked by a sheer scarf that wraps around hips and arms as it travels from figure to figure. In Pablo Picasso’s painting, the white swaths on the lower bodies of the two central figures may be a similar use of a fabric. Picasso’s flattened pictorial space prevents us from making a one-on-one comparison, but the Three Graces motif was so familiar by the early 20th century that the allusion would have been recognizable to viewers.

El Greco (Greek, 1541-1614) had been a prominent artist in Spain during the 16th and early 17th centuries, but by the early 20th century, his style had fallen out of favor and his work was rarely seen or discussed. In 1897, the artist Ignacio Zuloaga, a friend of Picasso living in Paris, acquired El Greco’s painting The Vision of Saint John, and Picasso studied it closely. The scale of El Greco’s painting and its composition, a string of figures, mostly nudes, spread across the canvas, have a clear relationship to Les Demoiselles. El Greco’s use of strongly contrasting streaks of white in St. John’s garment and similar patches of white in the sky clearly influenced Picasso’s use of white in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

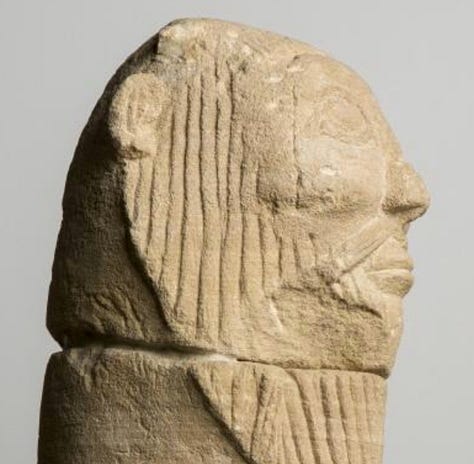

One of the noticeable elements in Les Demoiselle d’Avignon is the mask-like faces of the women. The simplified staring faces of the three figures to the left of the composition were probably based on ancient sculptures from the Iberian peninsula. The stony brown face of the leftmost figure is a very specific reference to such sculptures. Picasso saw examples of Iberian art at the Louvre, where recently excavated examples were displayed beginning in 1904, and he spoke openly about their connection to Les Demoiselles.

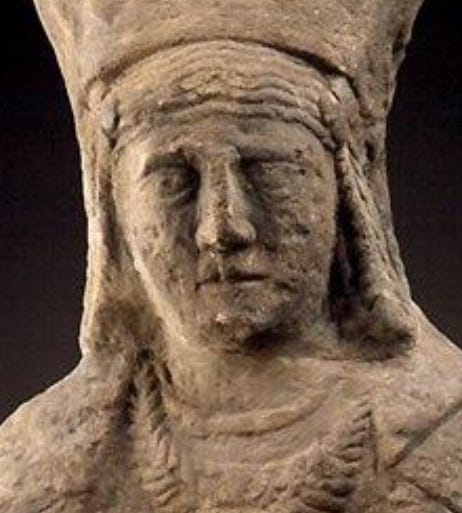

The other two faces are based on African masks which Pablo Picasso would have seen at the Musée del Trocadero (the former French national museum of ethnographic collections), in private collections, and in illustrated books. Unlike his openness about the influence of Iberian art, in the 1930s Picasso denied knowledge of African sculpture, in spite of his early 20th century interest having been documented by his friend Guillaume Apollinaire and others. In spite of his later denial, we must count Pablo Picasso among the many European artists in the early part of the 20th century who were fascinated by the art of tribal cultures. One of the attractions of these tribal arts is their use of abstraction and stylization, but for many artists, they also symbolized the primal origins of humanity.

In the period since its creation, this painting has been interpreted from many viewpoints. It is quite obviously not straightforward in either its representation or in its meaning. For some, it was simply an example of Picasso exploring new forms and style qualities in his path toward Cubism. The size of the painting alone suggests that the artist saw it as an important landmark in his career. In European painting from at least the 17th century on, large paintings were regarded as important statements of artistic philosophy and Pablo Picasso was deeply familiar with the traditions of European art. Most recently, art historian Suzanne Preston Blier has suggested that each of the five women in Picasso’s painting represents a different geographic area signified by the style in which she is painted.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was purchased by the Museum of Modern Art in 1937 and from that date the painting’s fame has grown. Today, it is accepted as one of Picasso’s most important works and as among the greatest monuments of Modern art.

One of my favorite paintings by Picasso, I have always been baffled by the initial reaction to it from fellow artists. Your mention of Appollinaire reminded me of the Mona Lisa incident. Someone should make a movie about it. In any case, the facial features of the woman to the left remind me of indigenous women from South America and how they have been depicted in the paintings of Guayasamin, or Kingman.

I admire this lucid and erudite study of the painting.