Welcome to the eighth edition of Chance Encounters. My topic is Lyrical Abstraction, a style which I really love. As its name suggests, Lyrical Abstraction is effusive, emotional, and deeply felt by the artists and, it is hoped, by viewers. So before you read what I’ve written, I encourage you to experience the paintings. From the email, click “open in the app or online” in the upper right hand corner. Once you are on the Chance Encounters 8 page on the Substack website, click an image to open a slide show of the works I’ve featured.

Swaths of color flow and pool across the canvas. Phenomenon: Sun Over the Hour Glass, 1966 by Paul Jenkins (American, 1923-2012) exemplifies Lyrical Abstraction, an important tradition in Modern and Contemporary abstraction. Lyrical Abstraction refers to painterly abstraction which demonstrates the artist’s process of making and emphasizes color as a means of self-expression. The term, coined in 1947 as “Abstraction Lyrique” by French art critic Jean José Marchand, has often been viewed as an attempt to compete with Abstract Expressionism which originated in the United States in the 1940s. The Abstraction Lyrique artists borrowed ideas from other European movements of the time. From Tachisme, these artists borrowed the use of stained canvas and from Art Informel, brushwork including drips and blobs that stresses the spontaneous creation of the works.

Paul Jenkins was in Paris in the early 1950s when Abstraction Lyrique was flourishing and the influence is clear. In Jenkins’ painting, the saturated pools of color in some areas contrast with colors that spread and blend in others. The effect almost denies the presence of an artist, seeming to have occurred organically, like smoke through the air or ink through water. This effect misleads us because Jenkins chose his materials, acrylic paint and primed canvas, and tools, including an ivory knife, to achieve his desired effect.

I do not stain and I do not work on unprimed canvas. This is more significant than it may appear. Staining or working on un-primed canvas results in an inkblot-like effect where the paint penetrates the canvas and spreads out on its own. When I work on primed canvas, I can control the flow of paint and guide it to discover forms. The ivory knife is an essential tool in this because it does not gouge the canvas, it allows me to guide the paint. (Paul Jenkins)

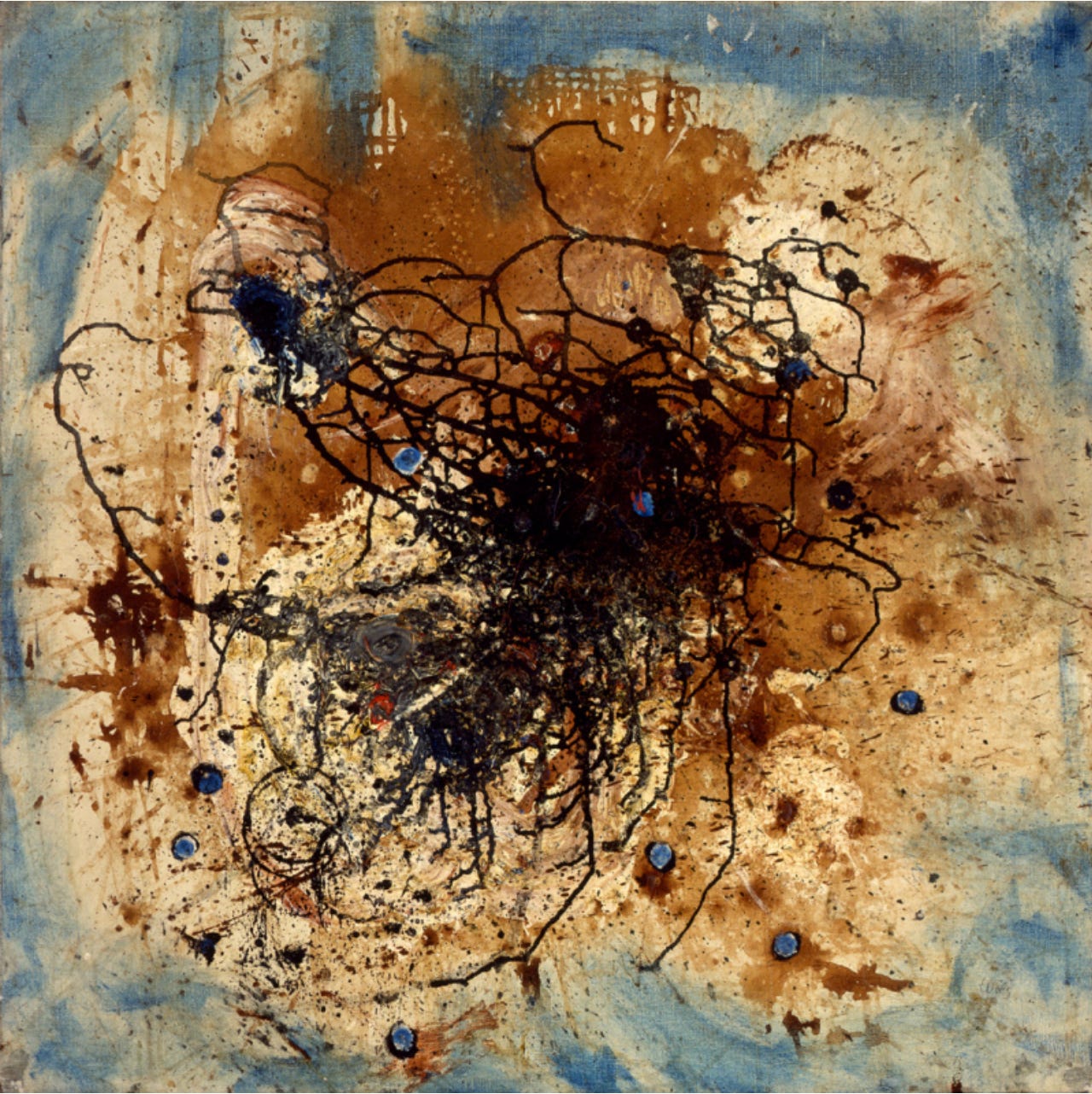

In the immediate post-World War Two period, artists from around the world returned to Paris and it was in this context that European Lyrical Abstraction arose. One of the pioneers of the movement was Wols, which is the name used by German painter and photographer Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze (1913-1951). Born into a wealthy art-loving family, Wols first became interested in photography and eventually moved to Paris in 1932. He established friendships with many artists before during and after WW2 including László Moholy-Nagy, Fernand Léger, and Max Ernst. He also established relationships with important writers and thinkers during the same period, most notably André Malraux, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Simone de Beauvoir. Though he had experienced some success with his photography, Wols focused on painting and print-making after the war. It’s All Over (1947) demonstrates his technique of combining stained areas of color, the blue and brown tones, with a drizzled and dripped relief structure over the top. Sadly, Wols died at age 38, just a few years after his participation in one of the first Abstraction Lyrique exhibitions.

The Chinese-French artist Zao Wou-ki (1920-2013) was among the multinational crowd of artists who flocked to Paris after World War Two, arriving shortly after the first exhibition of Abstraction Lyrique works. Though Zao’s early work in China had been figural, under the influence of what he saw in Paris his work shifted toward abstraction. Then in 1957, the artist visited New York and, inspired by the Abstract Expressionist and other works he saw there, began to paint in a bolder style on larger canvases. A couple of years later Zao ceased to give names to his paintings, instead titling them with the dates on which they were created. 2.6.61 demonstrates Zao’s mastery of color and his practice of contrasting smooth bands of atmospheric color with energetic patchy streaks and flickering brushstrokes.

Among the artists in postwar Paris were quite a few Americans including prominent Lyrical Abstractionist Sam Francis (1923-1994). In the 1950s, Francis worked in Paris and traveled around the world seeking inspiration and creating works like Shining Back, 1958. In addition to absorbing American and European influences, Francis began to study Japanese art and Zen Buddhism in this period and Japanese ideas remained an important component of the artist’s approach throughout his career. The splashed paint in Shining Back reflects Francis’ fascination with haboku, Japanese “flung-ink” painting. The contrast of deep blue with the white of the canvas plays an important role in Francis’ work, as seen here. The patches of color dripped across one another and the empty white areas of the canvas give a clear sense of the artist’s process of creation as well as a literal flow from the top of the bottom of the painting.

Painter Joan Mitchell (1925-1992) was another American artist who frequently visited Paris during the 1950s, before settling permanently in France by 1959. Her colorful gestural abstractions were influenced by the Abstract Expressionists, many of whom were close friends, and inspired by nature.

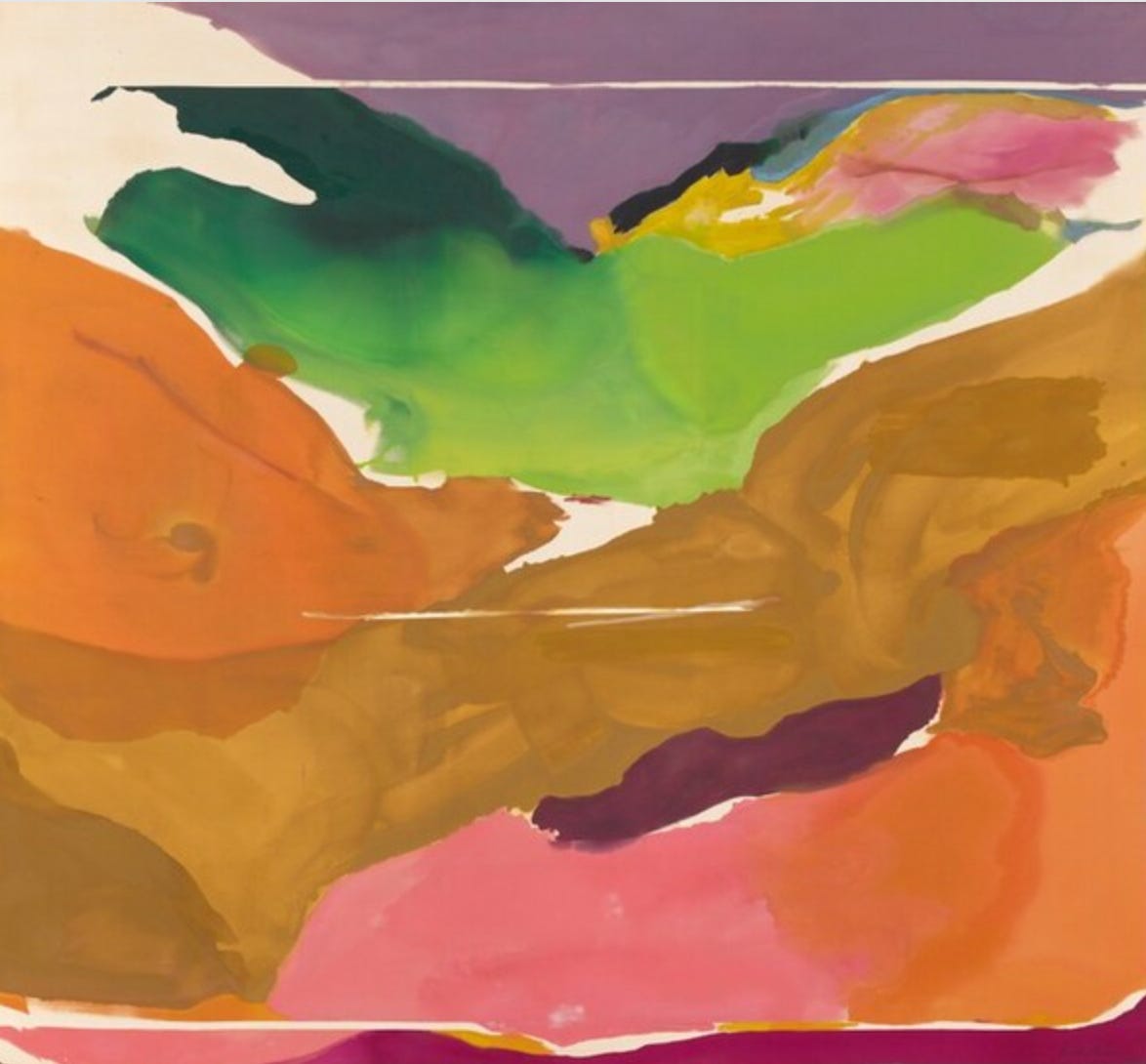

Sam Francis and Helen Frankenthaler (American, 1928-2011) represent an American tradition of lyrical abstraction which became especially prominent in the 1960s and 70s. Evolving from Abstract Expressionism, and especially from Color Field painting, American Lyrical Abstraction was a reaction against Minimalism and hard-edged abstraction that had supplanted Abstract Expressionism in the 60s and 70s. Inspired by watching Jackson Pollock spreading his canvas on the floor to paint, Frankenthaler followed suit. Her technique however, was quite different from Pollock’s.

What evolved for me had to do with pouring paint and staining paint. It's a kind of marrying the paint into the woof and weave of the canvas itself, so that they become one and the same. (Helen Frankenthaler, NPR 1988)

Nature Abhors a Vacuum, 1973, is typical of her works using thinned acrylic paint which she allowed to flow over and soak into unprimed canvas. The resulting painting suggests a natural landscapes but never depicts a specific place.

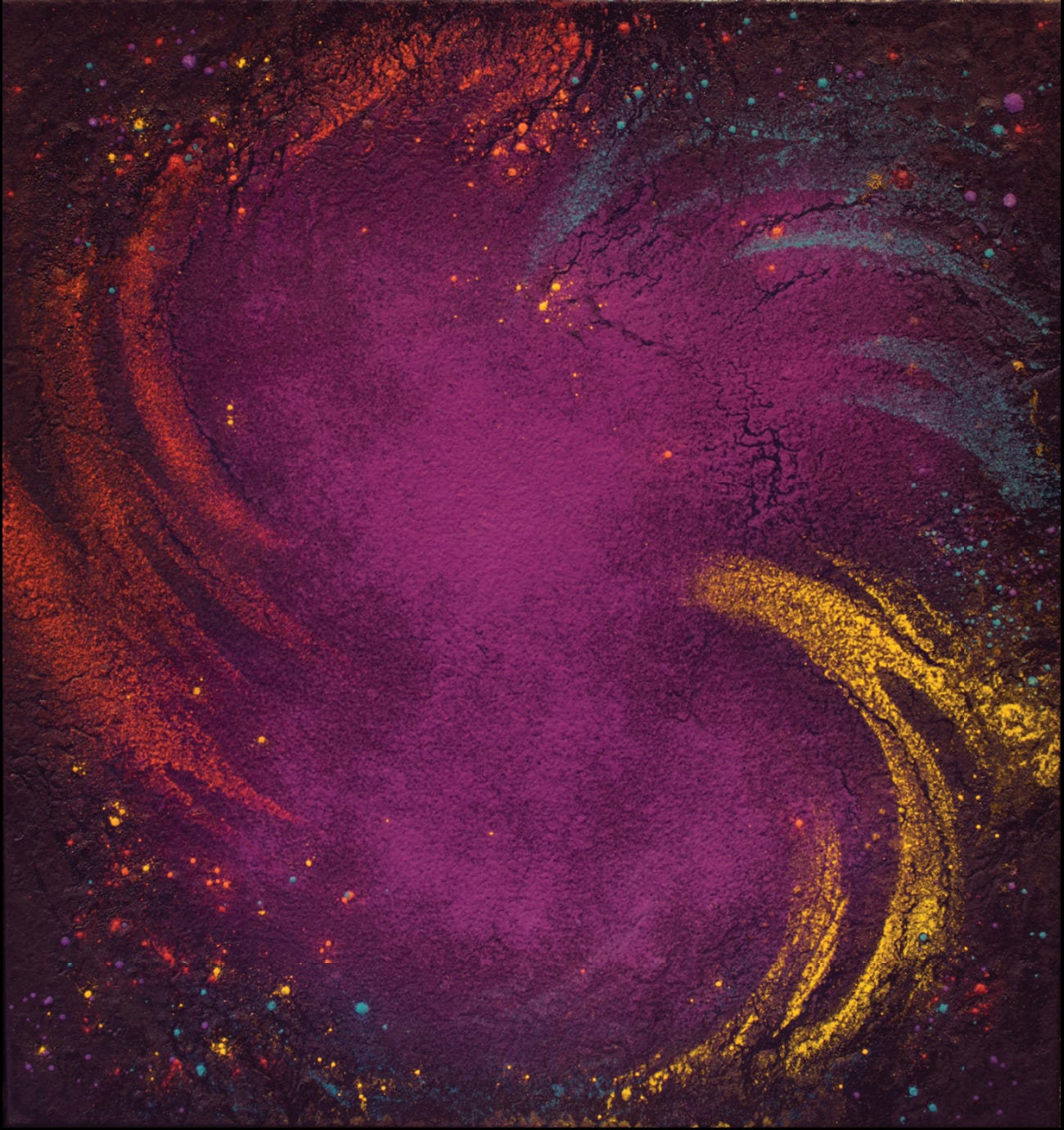

American artist Natvar Bhavsar (b. 1934, Gothava, India) explores the sensual, emotional, and intellectual possibilities of color since the the early 1960s. His earliest works were Cubist in nature, but he was inspired to shift to abstraction by Color Field and Abstract Expressionist art which he encountered when he moved to New York City where he still lives and works. Color is applied as dry pigments which Bhavsar sifts onto the support which has been soaked with a liquid binder that absorbs and holds the pigments in place. Like Frankenthaler, he places the support on the floor to allow easy access from all sides. The artist cites his Indian childhood experiences with vividly colored textiles, Indian sand painting (rangoli), and Holi festivals as the source of his passion for color.

I think I have tried to convey how to free oneself. Using color as a force to reach towards the beauty and generosity of the material that allows you unlimited expression. (Natvar Bhavsar)

In AMBEE, 1993, the dry nature of the pigment is apparent in the slightly granulated appearance of the surface. Bhavsar allow the movement of air and his body, including his breath, to disperse the pigment over the surface. The result looks rather like photographs of galactic structures such as nebulae and galaxies.

In the 1980s, Lyrical Abstraction fell out of favor with many critics. The works were considered too pretty, lacking in psychological depth or social commentary. It was a period when other practitioners of “pretty” styles were equally undervalued. Impressionism and Henri Matisse were also looked down upon for their commitments to aesthetic pleasure and beautiful colors. Still, the artists who had chosen Lyrical Abstraction continued working and have provided inspiration to later artists.

Contemporary American artist Dana James (b. 1986) builds intensely colored, complex surfaces from a variety of materials. Reused canvas and multiple paint media create textural contrasts that are as interesting as the color contrasts seen in her work. Her paintings often suggest elements being simultaneously revealed and obscured by layers of paint. In Memphis, 2022, the intense red edges of the painting and the way that pink overlaps the central red band suggest that this deep color is in the process of being hidden by the pink, but is managing to stay visible. This sense of an ongoing process of creation, in spite of this being a completed painting, harks back to many of the earlier works featured here. Dana James is a young artist whose works and growing success suggest that the history of Lyrical abstraction is far from over.

As always. I enjoyed your commentary, but did not see anything I liked, as your probably expected.

Lyrical abstraction was completely new to me, so thank you for the introduction! I shared my “find,” via your post, with an artist friend who, as I suspected, was very familiar with it and shares your strong appreciation. He actually sent on to me a piece he once wrote about Morris Louis’s work, which I thought you might enjoy: https://www.paintersonpaintings.com/archive/curt-barnes-on-morris-louis?rq=Morris%20Louis