As part of the region-wide Pacific Standard Time (PST): Art and Science Collide program, Louis Stern Fine Arts in West Hollywood, California, presents Helen Lundeberg: Inner/Outer Space. Helen Lundeberg (American, 1908-1999) was a key figure in two major 20th century American art movements: Post-Surrealism and West Coast Hard-Edge Geometric Abstraction. Although her career as an artist spanned six decades, this tightly focused exhibition centers on her “Planet” series, produced between 1964 and 1969 with supporting works on paper, as well as several conceptually and formally related examples of landscapes created later in her career.

The Planet series was created during the artist’s most productive period of hard-edge abstract work and at the height of the media frenzy and popular imagery associated with the space race between the USA and USSR. Unlike her contemporaries in the post-war geometric abstract movement, Lundeberg never fully abandoned reference to nature to become a purely non-objective abstractionist. Rather, the artist expertly distilled the most essential defining features of natural phenomena through careful observation, analysis, and understanding. She then created an imaginative abstract image of simplified planes of color that conveyed the experience or idea of that phenomenon. In this way her constructed forms, although wholly unlike any image of Jupiter, Saturn or Venus produced by NASA, are accepted by viewers as the depiction of a planet viewed through a telescope or from a position far above the planet’s surface. Lundeberg’s abstract paintings successfully unite objective scientific observation with subjective artistic vision.

In order to fully understand the significance of the Planet series, it is necessary to explore the artist’s biography and early career. Helen Lundeberg was born in Chicago, Illinois but moved to Pasadena, California at a young age in 1912. She attended Pasadena Junior College (now Pasadena City College) between 1927 and 1930 where she studied biology and astronomy. Pasadena is home to Caltech and the Mount Wilson Observatory where, in the 1920s, astronomer Edwin Hubble viewed a pulsar in the Andromeda Nebula, allowing him to measure the distance between it and the Earth. His work proved conclusively that Andromeda was a distant galaxy far outside our Milky Way, fundamentally changing our understanding of the size of the universe and our position in it. It was in this environment of profound scientific advancements that Lundeberg began her studies. Her notebooks at the time show an interest in astronomy and an aptitude for scientific diagrams of biological forms, dissections, and microscopic views of microorganisms. She was inspired by several accomplished women who accompanied scientific expeditions to create watercolor illustrations of biological specimens. Because opportunities in the sciences for women were limited, Lundeberg enrolled in the Stickney Memorial School of Fine Art with the intention of pursuing a career as a scientific illustrator. During this time, she received instruction from Lorser Feitelson (American, 1898-1978), who taught a rigorous course of study of Italian Renaissance painting. His method of diagraming the compositional elements of classical artwork appealed to Lundeberg’s analytical approach to scientific visualization and diagraming observed natural phenomena. She soon developed a keen interest in fine art painting and transitioned entirely to pursuing a career as an artist with Feitelson as a mentor, later her husband and collaborator.

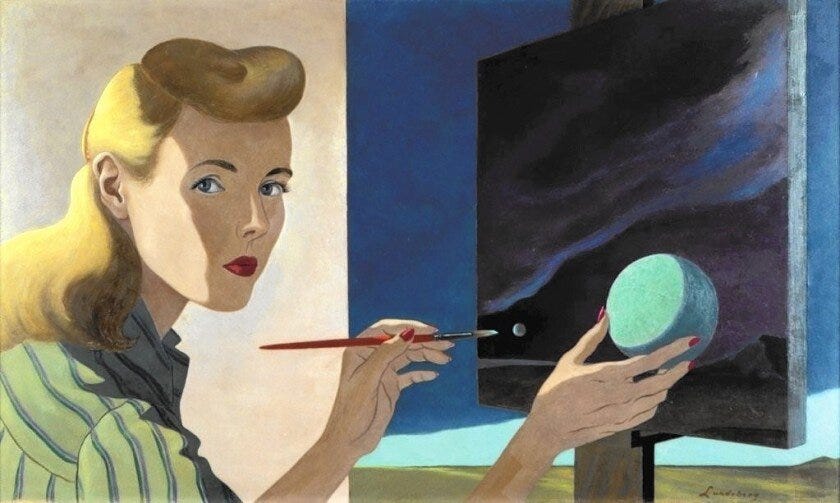

Lundeberg rapidly developed as an artist, primarily creating figurative work emulating the style of Italian Renaissance; however, she was also immersed in ideas of contemporary art movements unfolding in Europe, particularly Surrealism (see Chance Encounters, Edition 26 by Laura Heyrman). The artist approached the artwork and ideas of the movement with the same analytical rigor as she had biology and astronomy; however, she rejected European Surrealism’s use of automatism to tap into the unconscious mind. Instead, she believed that visual communication was best served by combining the harmony of classical compositional structure with a pre-meditated, intellectual approach to artmaking. In collaboration with Feitelson, Lundeberg authored and published her ideas under the title “New Classicism” which would go on to serve as the artist manifesto and theoretical foundation for what would later be dubbed Post-Surrealism.

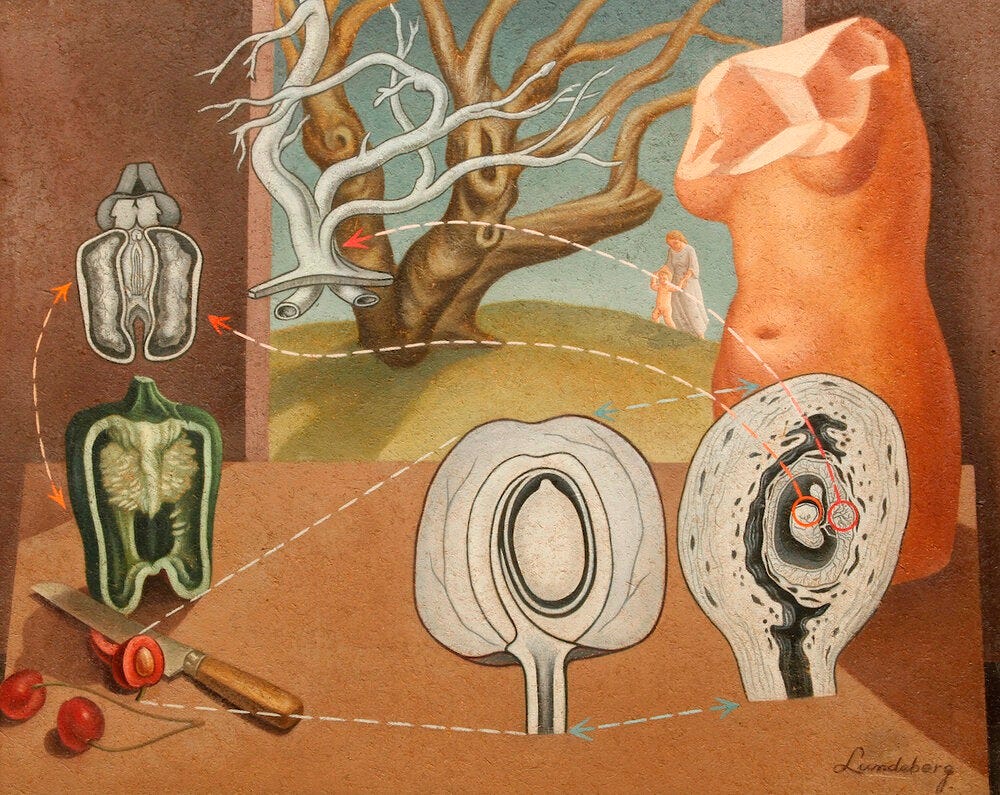

During this period her paintings were surreal figurative and representational compositions with scientific diagrams that sought to convey ideas about the connection between disparate observed natural phenomena. For example, in Plant and Animal Analogies (1934-35), which was reproduced to accompany her article “New Classicism,” she associated botanical seeds inside fruit and a mammalian fetus growing in the mother’s uterus, the tree’s branches and vascular structures, and the inside of a bell pepper with a cross-section of the human brain.

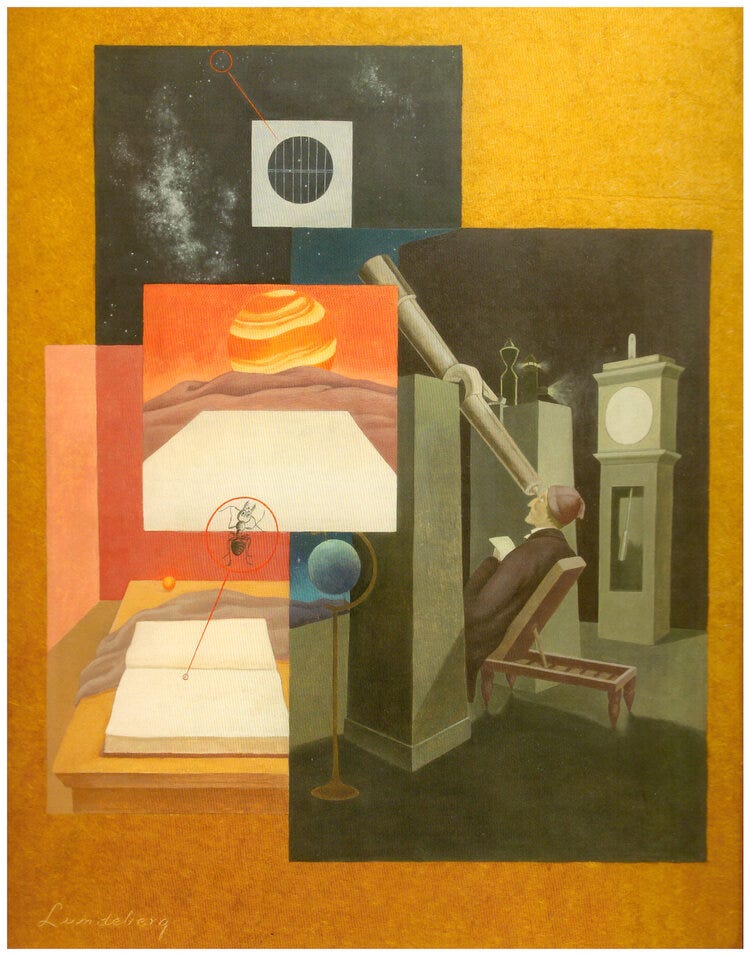

Lundeberg’s work frequently alluded to the grand scale of the cosmos, as well as a subjective observer’s perspective and the relative magnitude of structures observed through a microscope or telescope. The aptly titled, Relative Magnitude (1936) demonstrates Lundeberg’s incorporation of specific scientific imagery, such as the astronomer seated at a telescope, sourced from an 1860 image Speculum Hartwellian which was reproduced in a 1926 astronomy textbook in her possession, as well as accurate notation of star positions in the chart above. The specificity of those elements is offset by an imagined planet rise over a lunar landscape, painted thirty-two years before NASA’s famous Earthrise photo taken during the Apollo 8 mission. In the other direction of magnitude, the artist includes an ant crawling across the page of an open book which simultaneously magnified and projected onto the surreal planet-scape.

Lundeberg exhibited her imaginative figurative paintings in galleries in Hollywood, San Francisco, and Brooklyn, New York. The artist achieved national recognition when one of her paintings, Cosmicide (above), was included in the Alfred Barr-curated 1936 Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The accompanying catalogue did not reproduce the image though it described Lundeberg’s association with the “California Post-Surrealist Group;” however, it did so without citing her as the author of the manifesto on which the movement was founded. Although she continued easel painting, through the end of the 1930s Lundeberg shifted focus to creating murals for the Work Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project. In the 1940s, she returned to small scale studio work and continued to enjoy success nationally, including a second painting selected for the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition: Americans 1942: 18 Artists from 9 States, as well as a group show at the Art Institute of Chicago, and positively reviewed solo artist exhibitions.

Despite her success, frequent national exhibition, and positive critical acceptance of her lyrical figurative paintings, Lundeberg began to transition away from post-surreal representations towards simpler compositions of unmodulated fields of color with crisp borders that would later define Hard-edge Geometric Abstract Classicism. In the early 1950’s, the artist was painting primarily still-life objects arranged in atmospheric interiors or figures and trees in dreamy exterior landscapes. The architectural elements, such as walls, doors, and windows became simple planes of flat color. In a critical moment of insight, Lundeberg realized that what she had been thinking of as backgrounds painted to contain objects, trees, or figures were complete, stand-alone paintings. The atmospheric space became the painting’s subject which in spite of the simplicity nevertheless conveyed a mood, emotion, or sense of location, such as Day and Night, (Cloud Shadows), 1959-1960 above.

During the late 1950’s and 1960’s while working closely with other Los Angeles based artists, including her husband Lorser Feitelson, Karl Benjamin, Frederick Hammersley, and John McLaughlin, she contributed both theory and formal elements to an art movement variously described as California Hard-Edge, the LA Look, West Coast Minimalism, or Light and Space Art. The artists were unified by both region and the formal qualities of crisply defined flat planes of color devoid of brush stroke, modulation, or shadow, in carefully constructed abstract configurations. The movement was recognized by critics as a reaction against gestural Abstract Expressionism or action painting of Pollock and de Kooning (see Chance Encounters, Edition 23 by Laura Heyrman). In addition to formal differences, the artists of the Hard-edge movement prioritized a more universal or inclusive relationship between artist and viewer rather than idiosyncratic, intense subjectivity of the artist’s psyche found in Abstract Expressionism.

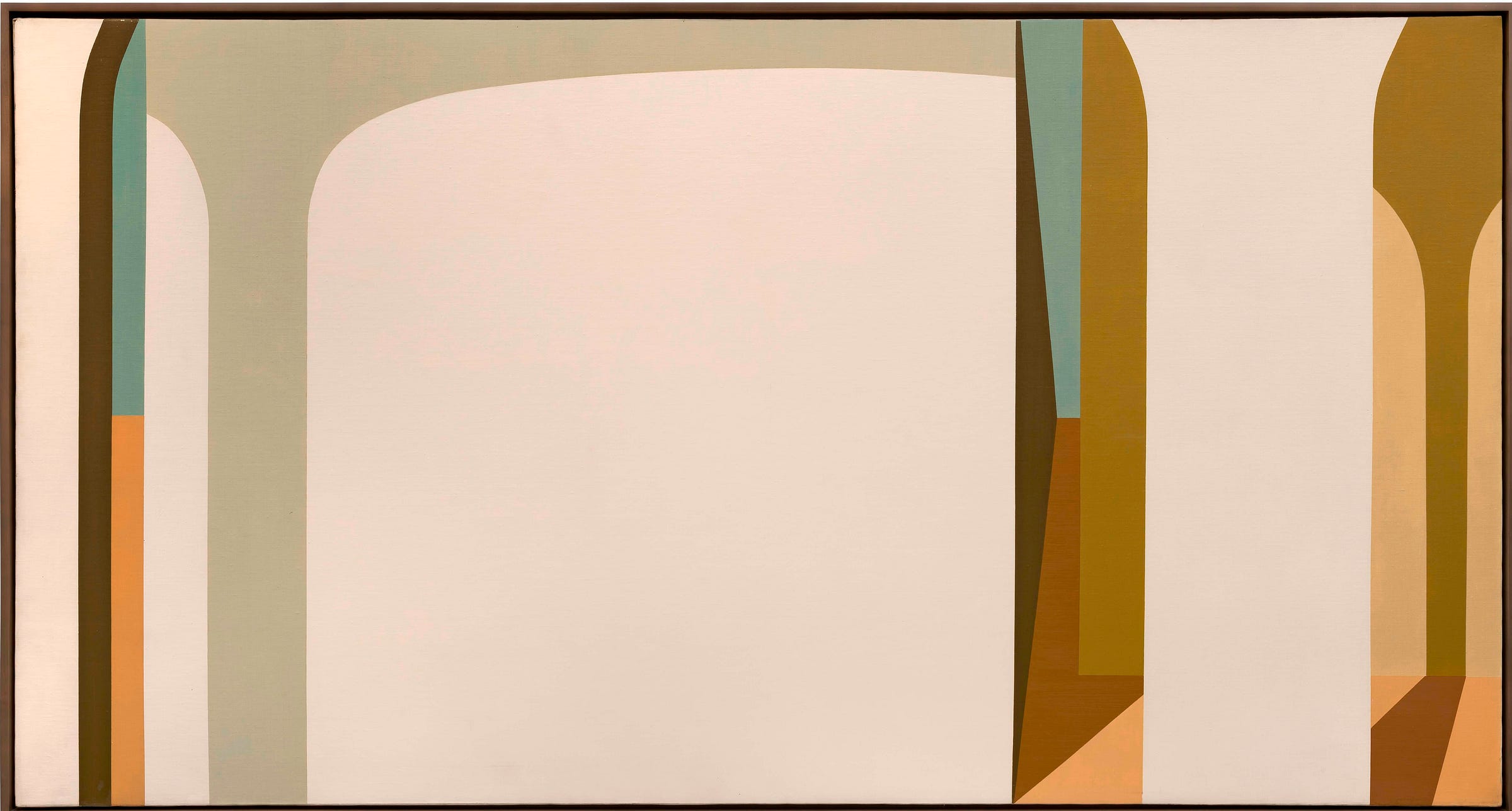

Lundeberg strongly believed that the viewer completes the artwork when they experience the sense of place, mood, or emotion intended by the artist. For this reason, she attempted to follow physical rules and maintain the appearance of structured reality even as she simplified the composition, removed details, and denied viewers a specific, real location in her work. For example, in Arches V (1962) although not painted from life, viewers recognize the white exterior of Mediterranean architecture under an intense California sun.

During this period, Lundeberg was a prolific painter creating many abstract color-field paintings, such as Interior with Table (1960) above. In the 1960s, the artist shifted to larger (60 by 60 inch), square canvases which furthered the sense of a flatter image as this format pushes the scene forward in the picture plane. Like many of her contemporaries, Lundeberg also stopped using frames and started fastening the canvas to the back of the wood support. This allowed her to paint all four sides as well as the frontal plane, treating the painting as its own physical object rather than a window to another world. Although she continued to become more and more distant from figuration, Lundeberg never joined her colleagues in becoming entirely non-objective. The artist always retained some degree of representation or reference to observed natural phenomena of light, shadow, and space, and the illusion of three-dimensional space.

I wanted to keep a sense of literal space and perspective but with the least possible means and to work for the harmony of the flat shapes themselves. – Helen Lundeberg

Between 1965 and 1969, perhaps inspired by the cultural excitement of the space race and depictions of planets and space exploration in popular fiction or published by NASA, Lundeberg returned to her earlier theme of astronomy and the cosmos to create the Planet series which serve as the foundation of the current exhibition at Louis Stern Fine Arts. However, unlike her earlier figurative depictions of scientific instruments and illustration of specific planets such as Saturn or Mars, the focus shifts to a view of an imaginary planet seen through the telescope or from a position high above the surface. To convey this to her viewer, Lundeberg presents an abstract circle of crisply defined bands of colors swirling on the surface centered in a large black square.

Previous essays on these paintings describe the black square as representing the void of deep space, but in nature the visual field surrounding a planet is not empty black, it is full of stars. Because she usually observed and accurately interpreted the structure of natural phenomenon in her work, if Lundeberg intended to position her viewer as if hovering high above the planet’s surface, she could have represented those stars as points of light pigment within the black square; however, the artist intentionally withheld stars from her final composition. In this way, her paintings more closely resemble an accurate view of an imagined planet surface seen through a telescope in which light is admitted through a circular aperture and peripheral vision is blocked out as uniformly black. The small studies for the planet series, included in the Louis Stern exhibition, closely resemble Galileo’s notebook entries depicting the moon as observed through a telescope. In both cases the artist depicts the circular surface of their celestial object centered in a black square devoid of stars. Although Lundeberg discards illustrative specificity of an identifiable planet, such as Jupiter or Venus, her imagined planets with discrete bands of color represent the successful union of the hard-edge geometric abstraction of her subjective artistic vision and her interest in preserving accurate scientific depictions of natural phenomenon.

In addition to the planet series, the Louis Stern exhibition includes several landscapes from later in the artist’s career which have significant visual similarities to the Planet series. Like her planets, the landscapes are constructed from sharply delineated bands of unmodulated color in a subtle range of hues. They do not represent direct observation of a specific location but are imagined landscapes composed to convey a sense of place with the least possible means. As in her earlier work, Lundeberg’s later paintings represent a clear artistic vision that seeks to create a shared perceptual experience with her viewer. Her artwork distills the accumulated views a lifetime of careful observations, analysis, and study into condensed abstract images with a universal appeal. Perhaps this is why, nearly fifty years later, her Planet paintings and late landscapes do not feel dated or locked in the decade of their creation, but feel fresh and contemporary to viewers today.

Helen Lundeberg: Inner/Outerspace continues at Louis Stern Fine Arts, 9002 Melrose Avenue, West Hollywood, California, USA, through November 2, 2024. Helen Lundeberg: Inner/Outer Space - Exhibitions - Louis Stern Fine Arts.

The region-wide exhibitions, lectures, and events associated with the Getty-led program PST: Art and Science Collide will continue through February 16, 2025. About | PST ART: Art & Science Collide.

Additionally, paintings by Helen Lundeberg will be featured at the Louis Stern Fine Art booth at The Art Show: Art Dealers Association of America, Park Avenue Armory, New York City, between October 29 and November 2, 2024. Press Release - The ADAA Art Show - Exhibitions - Louis Stern Fine Arts.

Yet another wonderful post from you that has introduced me to a fascinating artist. Thank you!