Our vision and intimate relationship to our communities are precisely what make Native photographers the people best equipped to convey the allure, strength, and complexity of contemporary Native life. – Cara Romero

Today, the works of Indigenous artists around the world are increasingly appreciated for their unique blending of cultural traditions and contemporary individuality. In this edition, I will look at a small selection of North American photographers whose works reflect the growing importance of Native voices. At the end of the essay you will find a list of some of the current and soon-to-open exhibitions in which these artists and their colleagues are featured.

Many Indigenous North American photographers are working to present their cultures as part of the modern world, not once-great societies lost in the past. Nadya Kwandibens (Animakee Wa Zhing, First Nation Anishinaabe-Canadian) creates the works in her Concrete Indians series in collaboration with her subjects. She finds her sitters through open calls and works with them to design the final image. In the photograph above, Tee Lyn Duke, a member of an Anishinaabe dance troupe wearing her jingle-dress regalia, stands in a major subway station interchange during rush hour. Kwandibens had Duke stand still as the flurry of commuters pass by – resulting in the sense that the Indigenous culture is permanent while rushing commuters seem like flowing water or a passing breeze.

Kwandibens was born in northwest Ontario, Canada, in the Animakee Wa Zhing First Nation and is now based in Toronto. In 2008, she founded Red Works Photography to uplift and empower Indigenous people, through her own images and through other projects. Since then, in addition to her expressive personal projects, she has employed her camera in support of important movements like Idle No More, a Canadian Indigenous group which began by protesting government violations of treaty rights and now promotes indigenous rights and equality issues, environmental issues. Kwandibens has also worked with the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIWG2S) project since 2019. In 2023, the artist was named to a three year term as Toronto’s photographer laureate.

The main thing I hope is they see that Indigenous people are beautiful; our cultures are vibrant and thriving; and we are persisting and resisting. I hope people see that’s there’s definitely an Indigenous presence in the city and there always has been. We’ve been here since time immemorial. – Nadya Kwandibens

Eugene Tapahe (Diné (Navajo)-American, b. 1968) began to pursue a career in photography when he was in his mid 40s. He abandoned a steady job with benefits for the less certain world of art, determined to use his photography in pursuit of the traditional Navajo concept of hózhó, meaning harmony, balance, and beauty. Like Kandibens, the artist has used his photographs to bring attention to the MMIWG2S project. The red scarves hanging at the young women’s waists in Tapahe’s Strength in Unity promote awareness of the problem of missing Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit people. However, this photograph, and the larger art Heals: The Jingle Dress Project of which it is a part, have a much larger goal, a universal healing of land, people, and spirit. The project originated during the COVID-19 pandemic, when Tapahe’s growing photographic career was halted by widespread closures. One night the artist dreamed of being approached by women dancing in jingle dresses, a ceremonial garment of the Ojibwe culture. Inspired by the sense of peace the dream had brought him, he began working on the project that has since brought him national and international renown. He travels with his two daughters and two other Diné women, visiting culturally and nationally significant places like National Parks, Native sacred sites, and national Monuments. There the young women perform a healing dance and are photographed and filmed.

Photographer Seeks Healing Through Art, produced by Brigham Young University, 2024

Looking at them, I still can't believe I took these photographs. I believe this project is larger than myself, and I hope that when people view them, they feel the same way – that we are all blessed to be in the presence of such beauty. – Eugene Tapahe

Nicholas Galanin (Tlingit-Unangax̂-American, b. 1979) is a multi-disciplinary visual artist and musician whose works are collected by many museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, Art Institute of Chicago, and Los Angeles County Museum of Art. As a child he learned jewelry making and metalsmithing from his uncle and father. This background led him to take a degree in those areas at London Goldsmiths College. In addition to apprenticeships with master carvers and jewelry makers, he received an MFA in Indigenous visual arts from Massey University in New Zealand. The photograph above documents his Land Art project Never Forget, an installation near Palm Springs, California. (Steel and paint, 59.3 ft. x 360.6 ft. l 18.1 x 190.9 m.), which was part of the 2021 outdoor Desert X biennial. Visually, the artwork refers to the famous Hollywood sign and so conjures meanings associated with that site, originally an advertisement for a whites-only real estate development and now internationally famous as a symbol of the American film industry. Located near an entrance to the Cahuilla Reservation, the installation spells out the phrase “Indian Land,” which dates back to 1979 and has been used at other Native protests over the decades since. Through this work he connects the modern concepts of Land Art with traditional Indigenous connection to their land.

Culture is rooted in connection to land; like land, culture cannot be contained. I am inspired by generations of Lingít & Unangax̂ creative production and knowledge connected to the land I belong to. – Nicholas Galanin

Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie (Diné (Navajo)-American, b. 1954) is an artist, author, teacher, and museum director who uses photography to reappropriate Native Americans as subject matter. Her original goal had been to pursue painting as a career, but turned to photography when she was criticized for the “ethnic subjectivity” of her work.

There exists a deep passion within my being to gather dreams and visions. … When constructing dreams and visions, I find that collages work well. The cutting, pasting, and choosing is followed by another favorite of digital construction, ultimately rendering the vision seamlessly. – Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie

We’wha, The Beloved is an example of the artist’s digital collage works and a process of rematriation, that is, taking an image created by a non-Native maker and transforming it with an Indigenous perspective. The idea of rematriation extends beyond the visual arts and includes recovering Indigenous cultural lands, remains, and artifacts. The term was chosen by scholars to honor the matrilineal traditions of many Indigenous cultures.

The subject of this work is a known two-spirit person, spiritual leader and cultural ambassador of the Zuni. We’wha (1849-1896) was a pottery and textile artist who spent time in Washington, DC demonstrating their crafts in hopes of creating understanding of the Zuni culture at a time when the federal government was attempting to assimilate Indigenous peoples into non-Native Christian culture. Because of their extensive interactions with the dominant culture, We’wha is the most famous two-spirit individual (lhamana in Zuni) on record. Newspapers and individuals were fascinated by We’wha because they presented as a woman when in Washington; very few Native women participated in the numerous Native delegations of the late 19th century. At home, We’wha participated in both male and female traditional activities and ceremonies. Their early death, about age 46, was deeply mourned in their community

As the basis of her collage, Tsinhnahjinnie appropriated a late 19th century photograph taken by John Hillers (German, 1843-1925), a print of which is in the Bureau of American Ethnology Collection of Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. The artist has transformed the sepia original into a vibrant image filled with symbolic plants and animals. The iris often symbolizes integrity among the Diné (Navajo), the artist’s culture, while the red dragonfly symbols represent the agility of a warrior. Swans may signify a connection to the supernatural in Zuni culture. The halo form surrounding We’wha’s head conveys the subject’s importance in both Native and non-Native contexts. The artist also identifies as two-spirit, so We’wha must be an especially meaningful theme for her.

Wendy Red Star (Apsáalooke (Crow)-American, b. 1981), a prominent Indigenous artist and curator, also appropriates historical photographs for her work. She is the curator of the exhibition Native America: In Translation, currently at the Asheville Art Museum and was a 2024 MacArthur Fellowship recipient. Her uncle and grandmother were also artists, providing role models for a creative career. Though I am focusing on a photographic work here, Red Star also works in sculpture, fashion design, bead work, fiber art, performance and painting. The artist uses her work to share her knowledge, using humor to break down barriers and presenting her subjects as human beings rather than stereotypes to challenge colonialism and racism. Red Star conducts extensive research into her subjects and uses that information to enhance her work.

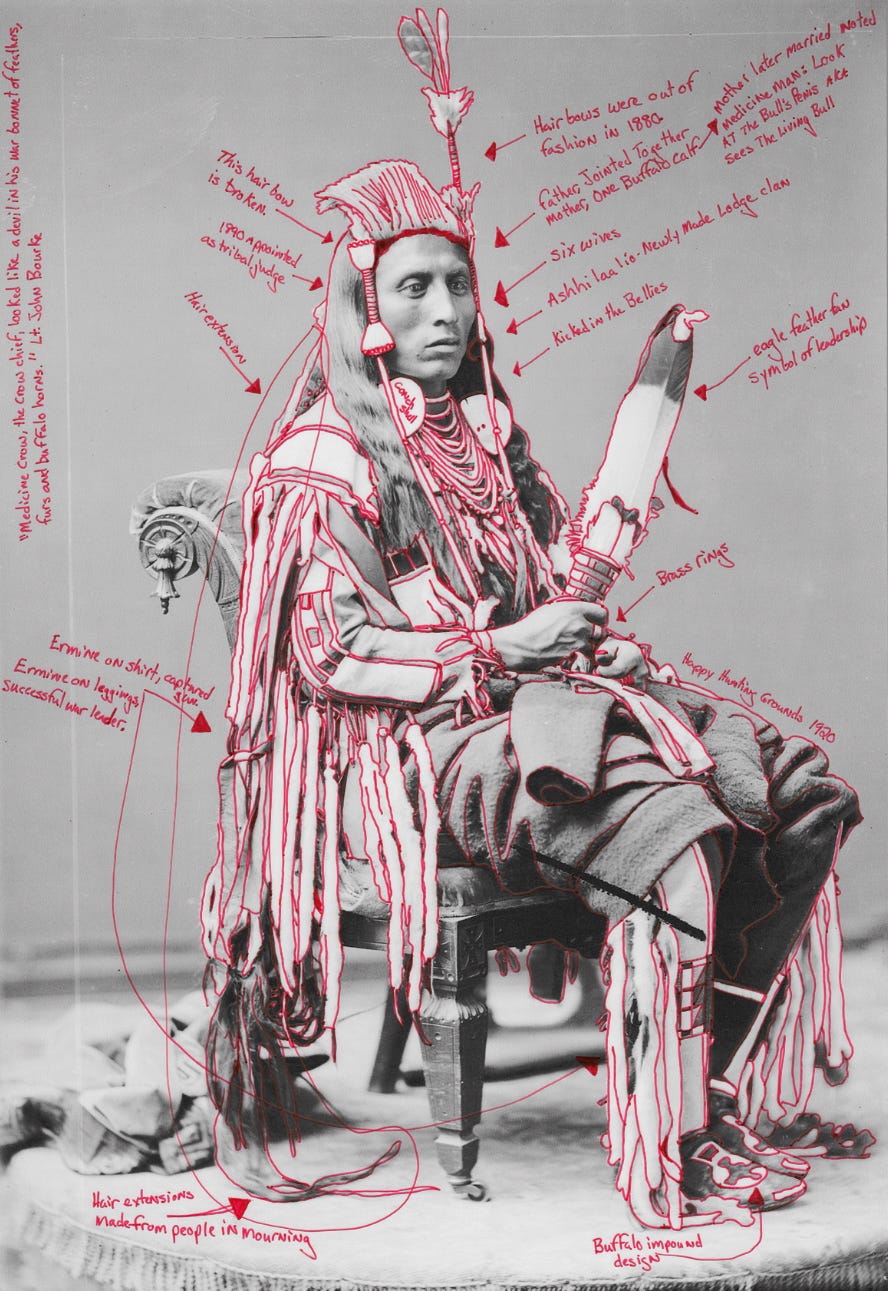

Peelatchiwaaxpáash / Medicine Crow (or Raven) is one of a series of 10 images in which the artist manipulated a digital version of a 19th century photograph by Charles Milton Bell from the National Anthropological Archives of the Smithsonian. The 10 images are portraits of the six Crow chiefs who came to Washington in 1880 to talk to President Rutherford B. Hayes because the railroad was slated to pass through their hunting territories. In Red Star’s work, red outlining and annotations highlight aspects of Medicine Crow’s regalia. The annotations explain symbolism and identify the chief’s family relationships. The long annotation on the left side of the image is a quotation from Lt. John Bourke (1846-1896), a prolific diarist and recorder of his experiences in the military and with Native peoples: “Medicine Crow, the Crow chief, looked like a devil in his war bonnet of feathers, furs, and buffalo horns.” Red Star’s other annotations contradict Bourke’s stereotyping The outlining is “redrawing” the borders of the photograph, a subtle reference to the way that these leaders were gradually coerced to cede territory and redraw the boundaries of their lands. How one communicates their identity interests the artist. Because she grew up on the Crow reservation but is mixed race, how one communicates their identity interests the artist. In the 1880 Crow Peace Delegation especially, she made note of anachronisms in the chief’s outfits. Here for example she notes that the bows in Medicine Crow’s hair were out of fashion in 1880.

When I was growing up, there was such pressure to prove one’s [Crow] ancestry that previous generations did not have. I was surprised to see that in these portraits, the tribal leaders from generations ago are wearing things from other tribes, like the Lakota or Cheyenne moccasins that Old Crow [another subject in the series] wears. I came to realize that the history of identity goes beyond surface value–there’s a complexity to it. – Wendy Red Star

The complexity of identity concerns many contemporary artists, but it also interested some earlier artists. One of the first professional Native American photographers, Horace Poolaw (Kiowa-American, 1906-1984) was rarely able to make a living from his pictures. He worked odd jobs and sold picture postcards made from his works to earn money. The artist focused on capturing his people; as a result he captured the changes experienced during his lifetime. Many of Poolaw’s works depict his and other Kiowa men in the military as well as their lives after service through photographs of veterans’ homecomings, honor dances, Kiowa military societies, and funerals. Fully aware of the importance of his work, the photographer stamped his works “A Poolaw Photo, Pictures by an Indian, Horace M. Poolaw, Anadarko, Okla.” His family has reported that he didn’t want to be remembered for his photography but wanted his photographs to help his people remember themselves.

Poolaw enlisted in the Army in 1943 working as an aerial photography instructor; he served until 1945. This staged image shows two Kiowa solders inside a plane. They wear flight suits and seem intensely focused on their military roles. At the same time, they wear feathered headdresses identifying their Kiowa ancestry. Poolaw is in the foreground, while beyond him Gus Palmer takes the role of gunner. This work shows a playful attitude but also makes a serious point about the contrast between stereotype and reality, a theme which is still being addressed by many contemporary Indigenous artists.

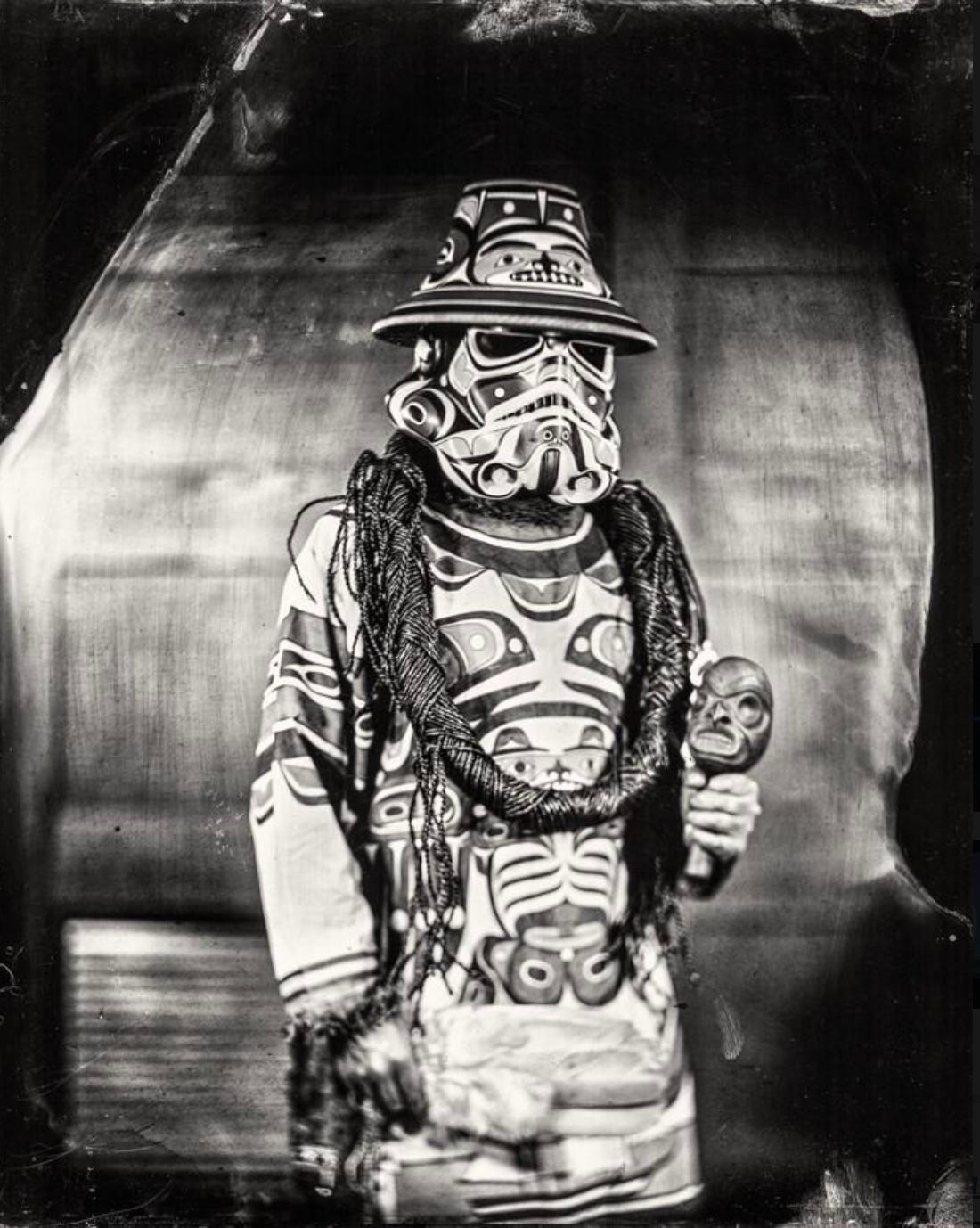

Will Wilson (Diné (Navajo)-American, b. 1970) has used his photographs in support of his environmental activism and his search for visual sovereignty, that is, the right of Indigenous people to determine how they will be represented. Wilson has three ongoing projects: Connecting the Dots, consisting of sculptures and photographs inspired by the large number of abandoned mining and ore processing sites on the Navajo Nation; Auto Immune Response (AIR) in which manipulated photographs show Navajo people in post-apocalyptic landscapes; and Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX), cooperative photographic portraits which challenge the stereotypical images of Native people taken in the 19th and early 20th centuries. K'ómoks Imperial Stormtrooper (Andy Everson), Citizen of the K'ómoks First Nation is from the latter series in which Wilson invites sitters to wear and bring whatever they wish to their sitting. Though he often uses cutting edge technology in his other series, for CIPX, the artist uses the wet collodion process (sometimes called tintype) which was used by the early 20th century photographer Edward Curtis (American, 1868-1952) whose photos of Native peoples were published in the twenty volume The North American Indian, between 1907 and 1930. These photos are still reproduced in textbooks and articles today and are part of the reason many people imagine that the cultures of Indigenous peoples dies out long ago.

Wilson’s portrait of Andy Everson looks like an old photograph due to the historical technique the photographer used and the uneven black areas at the edges of the image. At first glance, it appears to depict a member of the K’omoks First Nation, based in British Columbia, Canada, dressed in ceremonial regalia. Only upon closer look does it become apparent that the mask work by the subject is based on the Stormtrooper costume from the Star Wars films. The non-Native viewer is again faced with a blending of the contemporary and traditional that challenges us to rethink assumptions about Indigenous people in the modern world. Wilson feels a responsibility to his sitters to present them in a way that will received with respect.

I think it's an exciting time for Indigenous photography. There are more people than ever before working in this arena. In many ways, we've done the work that enables the next generation of Indigenous photographers to not have to worry about these issues as much. – Will Wilson

Cara Romero (Chemehuevi-American, b. 1977) is arguably the most prominent Native American artist working today. Earlier this year (2025) she was identified as the most frequently exhibited living artist in the United States, including 8 current or soon-to-open exhibitions. Romero started out as a student of cultural anthropology but became frustrated by the focus on Native Americans as cultures of the past. At the same time, she took a photography class that stressed content over technical and compositional perfection. The artist changed course, studying both traditional and digital techniques. He earliest works were influenced by Edward Curtis, but she soon rejected that historicizing mode as inauthentic. Romero’s artworks confront the impacts of colonialization, celebrate resilience, and address issues of social and environmental justice through imagery deeply rooted in cultural heritage. Her most recent projects address Indigenous Futurism, a movement that applies Native ways of knowing and cultural perspectives to illuminate potential futures. In Three Sisters, Romer’s models are three close friends and frequent collaborators whose bodies are painted in vivid colors. Each model is painted with patterns associated with her cultural background: Ojibwe floral beadwork, Pueblo pottery, and a Plains parfleche or rawhide container pattern. The women’s reflective sunglasses and starry backdrop and cloudy base suggest they inhabit some otherworldly zone. The wires around the figures connect them to one another and to their surroundings, as Indigenous philosophies so often connect the people and nature. The title also hints at Native traditional knowledge, specifically three sisters planting (companion planting) of corn, beans, and squash. This work epitomizes Romero’s theatrical and often whimsical narratives.

This essay only scratches the surface of the extraordinary flowering of creativity among Indigenous North American photographers, itself only a small part of the abundance of Contemporary Native artistic practices. All of the artists here, and many of their colleagues, feel a deep desire to express their own identities in the world, to cease being defined by outdated stereotypes and one-dimensional narratives.

Let us claim ourselves now and see that we are, and will always be great, thriving, balanced civilizations capable of carrying ourselves into that bright new day. – Nadya Kwandibens

Selected current and soon-to-open exhibitions:

Native Pop! at The Newberry, 60 West Walton Street, Chicago, Illinois, USA,through July 19, 2025 https://www.newberry.org/calendar/native-pop

Cara Romero: Panûpünüwügai (Living Light), Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, USA, through August 9, 2025 https://hoodmuseum.dartmouth.edu/explore/exhibitions/cara-romero

Smoke in our Hair: Native Memory and Unsettled Time, at Hudson River Museum, 511 Warburton Avenue, Yonkers, New York, USA, through August 31, 2025 https://www.hrm.org/exhibitions/smoke-in-our-hair/

Eugene Tapahe, Art Heals: The Jingle Dress Project, at Monroe Gallery of Photography, 112 Don Gaspar, Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA, through September 14, 2025 https://monroegallery.com/

Cara and Diego Romero: Tales of Futures Past at Crocker Art Museum, 216 O Street, Sacramento, California, USA, through October 12, 2025 https://www.crockerart.org/art/exhibitions/cara-and-diego-romero-tales-of-futures-past

Travels to Albuquerque Museum, 2000 Mountain Road NW, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA, November 1, 2025 – February 8, 2026 https://www.cabq.gov/artsculture/albuquerque-museum/exhibitions-1/cara-and-diego-romero-tales-of-futures-past

Native America: In Translation, curated by Wendy Red Star;at Asheville Art Museum, 2 South Pack Square, Asheville, North Carolina, USA, through November 3, 2025 https://www.ashevilleart.org/exhibitions/native-america/

Weaving Words, Weaving Worlds: The Power of Indigenous Language in Contemporary Art, Zuccaire Gallery, Staller Center for the Arts, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York, USA, July 17-November 22, 2025 https://zuccairegallery.stonybrook.edu/exhibitions/index.php

Indigenous Identities: Here, Now & Always, curated by Jaune Quick-To-See Smith; at the Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, 71 Hamilton Street, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA, until December 21, 2025 https://zimmerli.rutgers.edu/art/exhibition/indigenous-identities-here-now-always

Future Imaginaries: Indigenous Art, Fashion, and Technology at The Autry Museum of the American West, Griffith Park, 4700 Western Heritage Way, Los Angeles, California, USA, through June 21, 2026 https://theautry.org/exhibitions/future-imaginaries

As a non-Native observer of these artists’ works, I have taken great care to respect their works and ideas. I have learned so much about these diverse individuals and the cultures they represent; I hope what I’ve shared inspires you to seek out more of their art. Thanks, as always, for reading and subscribing. We truly appreciate your likes, shares, restacks, and especially, your comments.

Another excellent post! Good research, insightful comments, many quotes from the artists themselves illuminating their work. I learn so much and come to appreciate the vastness and richness of artistic expression that is common to all of us.

Amen