How to Read Paintings: The Knife Grinder by Kasimir Malevich

A remarkable painting in the Cubist-Futurist style

By Christopher P Jones

Kazimir Malevich was a Russian artist who was not afraid to break with convention.

Even when it came to his own art, he had a habit of turning away from his previous creations and towards new styles of painting in the space of just a few months.

Malevich was most active at the beginning of the 20th century. During his painting career, he worked in a variety of styles over several decades, but his most important works occurred between 1912 and 1918 when he concentrated primarily on the exploration of geometric forms (squares, triangles and circles) and their relationships within pictorial space.

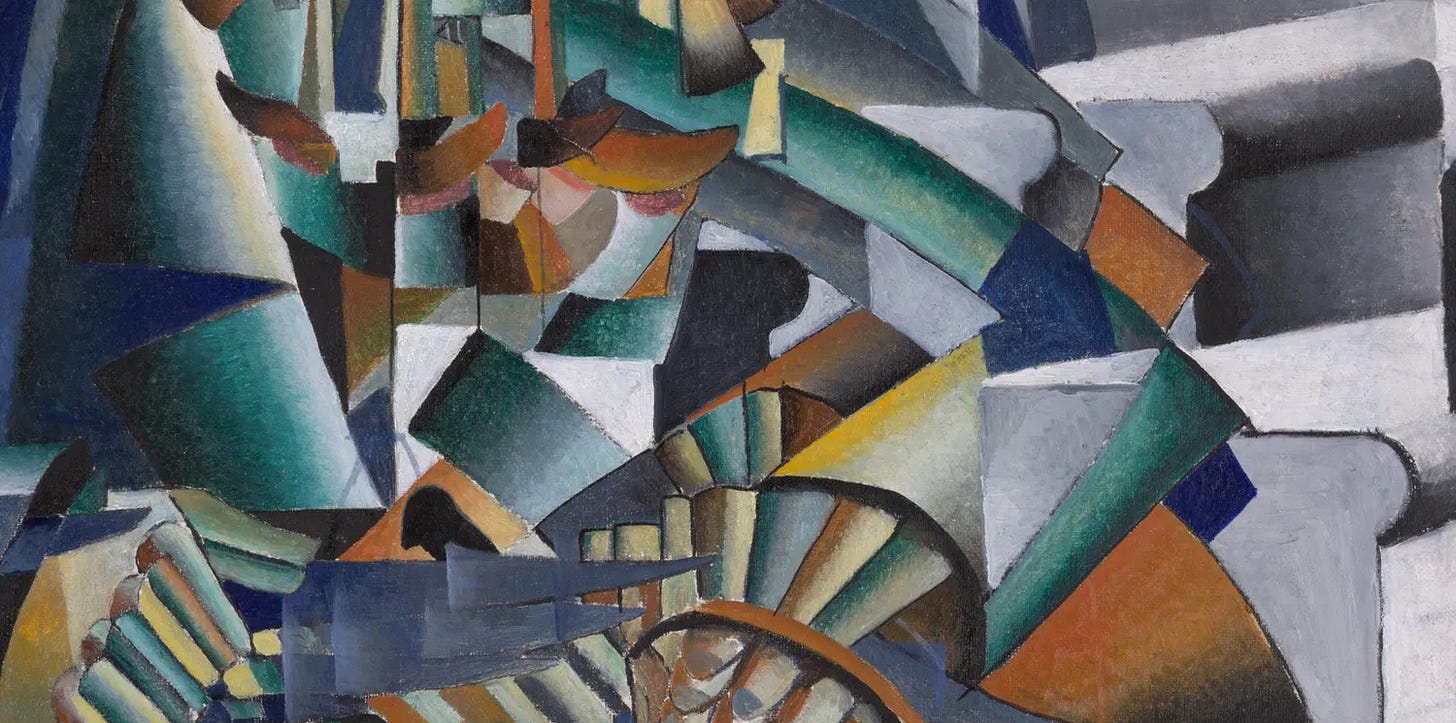

This painting, called The Knife Grinder or Principle of Glittering, was a crucial step on Malevich’s journey. With its fractured reality and repeated forms — like looking at the subject through a kaleidoscope — the work is a blend of Cubist and Futurist influences, and as such is considered one of the first and finest examples of Russian Cubist-Futurist painting.

Cubist-Futurist depiction

The emergence of Cubism from around 1907 provided many European artists with a revolutionary method of depicting the world around them.

Invented by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, Cubism sought to represent objects and figures in terms of fractured planes. The style embodied a new feeling for form as the modern world encountered it. As a style, it savoured the uneasy perception of splintered time and disintegrated space that modern technology and science seemed to inaugurate.

It also marked a revolutionary break with the traditions of European painting, where artists of the past constructed reality from a fixed viewpoint using devices such as linear perspective. With Cubism, there was no fixed viewpoint, just a collage of multiple points of view, often captured across several moments in time.

Malevich’s painting shows a man operating a knife grinding machine.

Malevich produced several pictures of peasants working at various tasks, and made this work as a sort of tribute to manual labour. Although rendered in a stridently abstracted manner, the large and perhaps noble figure of the knife grinder is clearly visible among the shards of painted colour.

Try spending some time looking at the image and notice how it almost moves before your eyes. The most intense passages of the painting occur around the man’s head and hands. Also, notice the area around the machinist’s left foot, where the shapes are repeated as the foot pushes the pedal up and down.

Uncertain times

Malevich painted this work during a time of rapid change in Russia. Much like Western Europe, the fabric of Russian society was experiencing dramatic upheaval as the industrial revolution brought shifts in economic and social foundations. And as the First World War approached, a new challenge to the monarchy of Tsar Nicholas II would soon see a political revolution in Malevich’s homeland.

Young Russian artists were galvanised by the sense of change. At the same time, they were becoming aware of new art movements in Paris. Malevich himself visited the French capital in 1912 and returned full of enthusiasm for the work of Picasso and Braque and the Cubist art they were making.

Another inspiration was the Italian artist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who represented the Futurist group of painters. Futurism’s emphasis on energy and movement, technology and the violence of modern machines, along with Marinetti’s rabble-rouser message, excited Malevich.

Malevich quickly assimilated these avant-garde styles into his own paintings. Over a short period, his works adopted many of the visual techniques of Impressionism, Fauvism and Cubism, followed by the influence of Italian Futurism.

The Knife Grinder painting is really an assimilation of all these different channels of influence. Every section of the picture plane is taken apart and reassembled to create the faceted effect. In making the work, Malevich transformed the labourer into a sort of magnanimous machine, a man of strength and vigour whose manual work has all the bearing of a great monument.

Rejecting Futurism

Malevich was not an artist to linger on one style of art for too long. Around this time, he became involved in projects beyond painting, most notably set-design and costumes for opera. In 1913 he collaborated with a young composer by the name of Mikhail Matyushin on an operatic piece called Victory over the Sun. The opera‘s theme was the triumph of technology over nature and modern man over the primal force of the sun.

Malevich soon adopted a more radical style of non-objective painting, for which he used the term “Suprematism”. Through the assemblage of geometric forms, he was seeking a purer form of Cubist-Futurism.

As if to prove the point, in 1915 Malevich took part in an exhibition held in Petrograd (now Saint Petersburg) with the title The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10 (pronounced “zero-ten”). Malevich had a room to himself. Of the thirty-six paintings he displayed, all were abstract works, many consisting of elemental crosses, circles or scattered arrays of rectangles.

To accompany the show, Malevich produced a pamphlet that described the intentions of his new art form. It was later republished with the title From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Realism in Painting. In the pamphlet, Malevich vehemently rejected “academic art” of previous generations. For Malevich, the very purpose of his new painting style was to assert the possibility of a complete aesthetic experience:

“I have transformed myself in the zero of form and dragged myself out of the rubbish-filled pool of Academic art.”

As for the Futurist manner, Malevich considered his new art to have eclipsed the art from which it was born, claiming, “We who only yesterday were Futurists, arrived through speed at new forms, at new relationships with nature and things”:

“We arrived at Suprematism, leaving Futurism as a loop-hole through which those left behind will pass.

We have abandoned Futurism; and we, the most daring, have spat on the altar of its art.”

© Christopher P Jones, author of "How to Read Paintings" & "Exploring Art History”. Find out more at chrisjoneswrites.co.uk