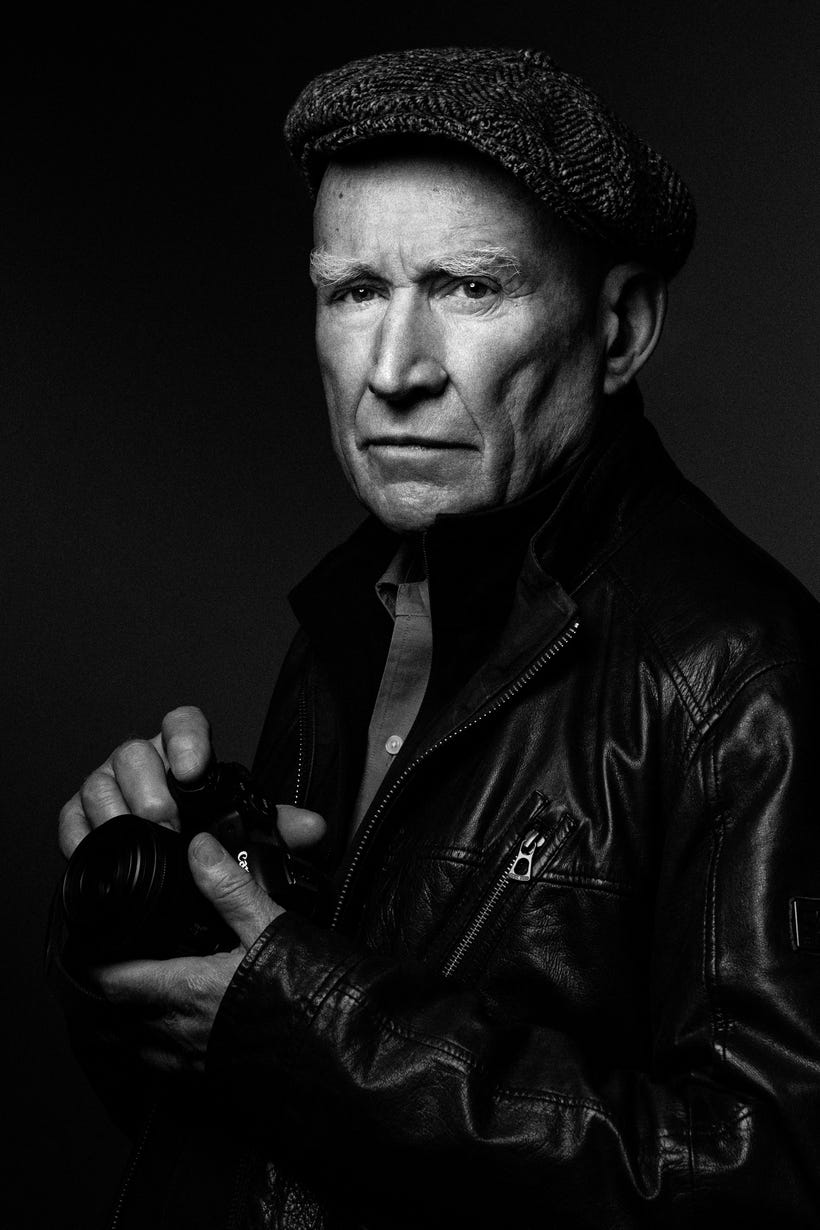

I adore photography, taking photographs, holding my camera, choosing my frame, playing with the light. – Sebastião Salgado

Brazilian photographer and environmentalist Sebastião Salgado (1944-2025) passed away on May 23. He was partly raised on his father’s farm where he learned his love of the land and respect for the people who worked it. Though Salgado began studying law as his father wished, he preferred economics and completed two degrees in that field. Upon graduating he worked for the Brazilian Ministry of Finance. He envisioned a career developing large scale projects that would benefit not only his country but the people who would be affected by the plans.

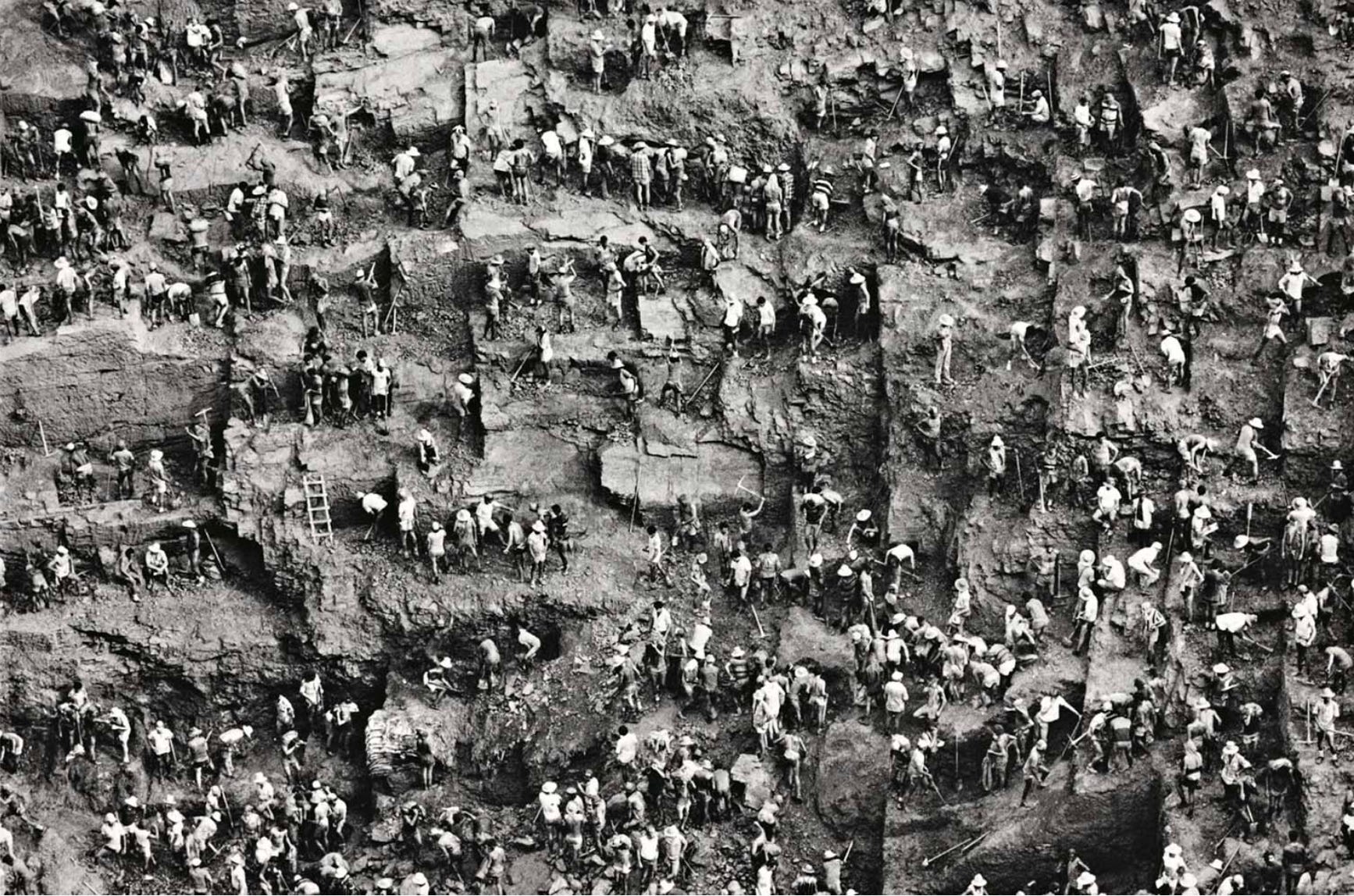

My first encounter with Salgado’s photographs was the image that opens this essay, one he captured during the gold rush at Serra Pelada in Brazil. (see more below) The photograph was included in a new edition of an art textbook from which I was teaching and I was immediately struck by the contrast between the sense of seething movement surrounding the casual stillness of the foreground figure. Some works of art have such a powerful effect on one that they stay with you, sometimes forever. For me, this photograph is such a work.

With the rise of a military dictatorship in Brazil in 1964, Salgado and many of his friends left the country in fear of persecution for their leftist political activities. Salgado and his wife Lélia Wanick Salgado settled in Paris, continuing their educations and their political activism. After completing his doctoral coursework, Salgado was hired by the International Coffee Organization which led to frequent trips to Africa, often contributing to projects for the World Bank. Fascinated by the people and places he encountered, he began taking photographs for his own enjoyment. Salgado soon realized that photography was the language he could use to understand the world.

In the 1970s, Salgado began photographing more seriously; he had some images accepted for publication in magazines and began to receive commissions for news assignments. He gravitated toward documentary projects, eventually focusing on self-assigned, long term projects intended for publication as books. Salgado spent seven years visiting Central and South American countries capturing moments of everyday life for his first book in 1985, Autres Ameriques (The Other Americas). Photographed in 1977, just four years after he’d embarked on his career as a professional photographer, Ecuador II was part of that first book. This image shows that Salgado had already developed the hallmarks of his style: conveying mood and personality through pose; sensitivity to texture, light and shadow; and compelling compositions.

Below are more of the images from the Serra Pelada Mine photographs which Salgado eventually published in 2019 as Gold. The photographs were captured in 1986, though, and first published in London in The Sunday Times Magazine. Salgado intended the photos to be part of his planned series on manual labor around the world. The mine itself originated with a child’s discovery of a 6 gram (0.21 ounce) gold nugget in 1979. Within a week, prospectors were flocking to the area. Eventually Serra Pelada became one of the world’s largest open-air mines, in some places as much as 70 meters (over 229 feet) deep, with up to 100,00 people working the site.

Every hair on my body stood on edge. The Pyramids, the history of mankind unfolded. I had traveled to the dawn of time. – Sebastião Salgado

This photograph conveys something of the scale of the workings. The blocky appearance of the mine’s landscape is the result if the system of allocating sections of the mine, approximately 2 by 3 meters (6.9 x 9.8 feet), to each owner who would employ the diggers. Salgado spent four weeks photographing the mine and its workers, living with the miners on site. This was characteristic of his working method for all of his long-term projects. He didn’t just want to get good images and go; he wished to understand the community as a group and as individuals.

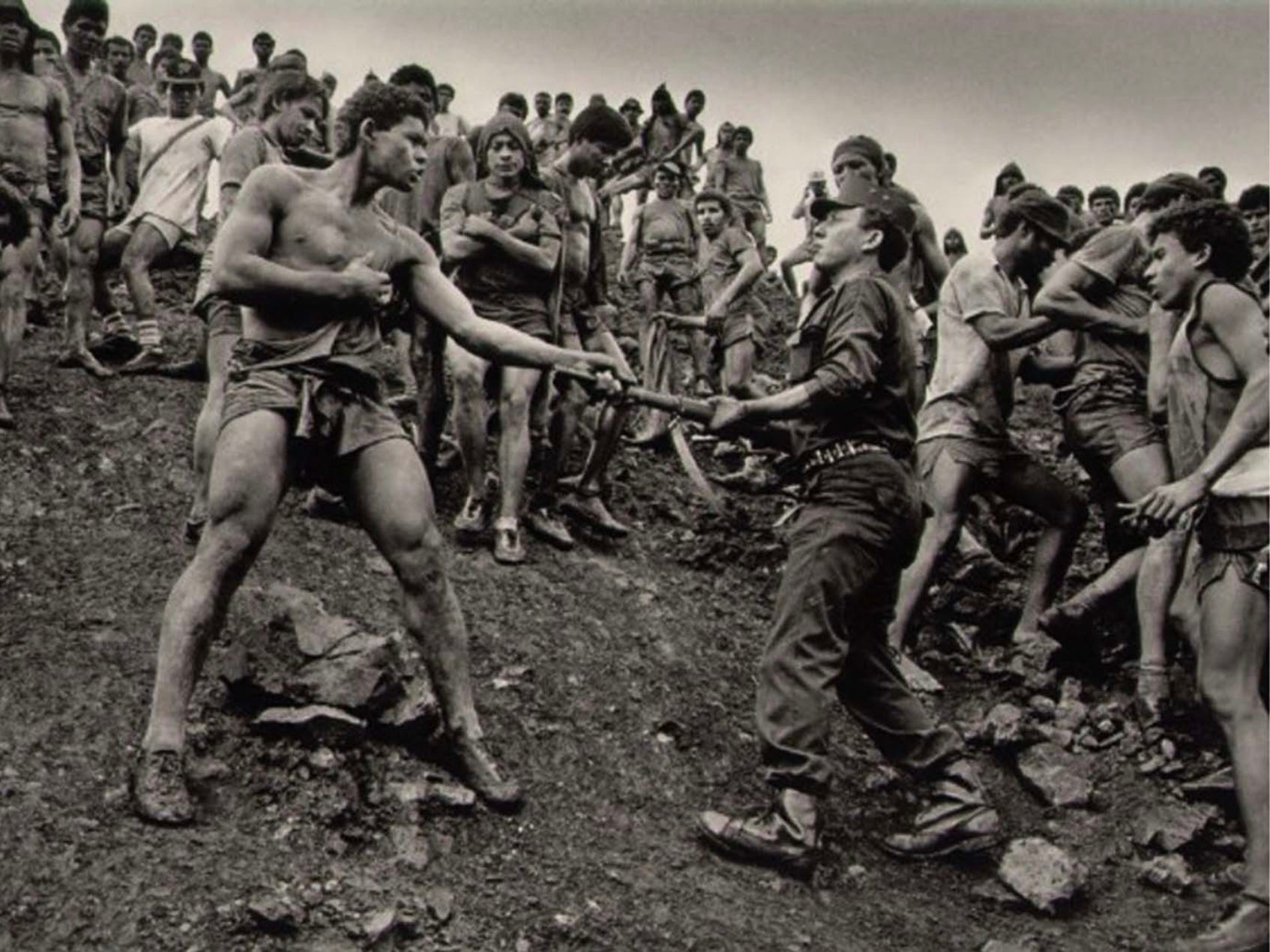

The conditions under which the miners worked are visibly terrible and most viewers understandably feel empathy or pity for them.

Swept along by the winds that carry the hint of fortune, men come to the gold mine of Serra Pelada. No one is taken there by force, yet once they arrive, all become slaves of the dream of gold and the need to stay alive. Once inside, it becomes impossible to leave. – Sebastião Salgado, 1992

Death and violence were always nearby at Serra Pelada. Violence broke out frequently. The police officers stationed throughout the mine to prevent fights were resented by the miners, as they were perceived to be trigger-happy oppressors. They fired their weapons readily and at times the miners turned on the police, pelting them with mud and rock. If one dug their sector too deep next to higher levels, there could be a deadly collapse. Not long after Salgado’s visit to the mine, collapses became so common that the site was declared too dangerous and deliberately flooded.

Every time a section finds gold, the men who carry up loads of mud and earth have, by law, the right to pick one of the sacks they brought out.

And inside they may find fortune and freedom. So their lives are a delirious sequence of climbs down into the vast hold and climb out to the edge of the mine, bearing a sack of earth and the hope of gold. – Sebastião Salgado, 1992

Anyone arriving there for the first time confirms an extraordinary and tormented view of the human animal: 50,000 men sculpted by mud and dreams.

All that can be heard are murmurs and silent shouts, the scrape of shovels driven by human hands, not a hint of a machine. It is the sound of gold echoing through the soul of its pursuers. – Sebastião Salgado, 1992

The diggers were called mud hogs because of the conditions in which they worked. On average, they were paid 20 cents for digging and bringing up each sack, which weighed between 30 and 60 kilograms (65 to 130 pounds). If gold was found, the digger would earn a bonus. The government had agreed to buy all gold found, at 75 percent of the London Metal Exchange price, and about 45 tons of gold was officially recorded coming out of the mine. It is estimated that as much as 90% of the gold found was lost to smuggling. Geological surveys suggest there could be an additional 20 to 50 tons of gold still buried beneath the lake that used to be the mine.

The process for separating gold from the surrounding materials, in the 1980s and still today, involves the use of mercury and endangers the health of the miners as well as causing widespread environmental poisoning. The deep lake and waters surrounding the Serra Pelada mine site are still contaminated and those who eat fish caught downstream from the site suffer from elevated mercury levels.

The publication of the Serra Pelada photographs established Salgado’s reputation and helped to revive the tradition of black and white documentary photography. He was much in demand for commissions and used his paid work to support the ambitious long-term projects. The project for which he had originally taken the mining photographs was published in 1993 as Workers: Archaeology of the Industrial Age.

In the decades since Salgado photographed Serra Pelada, the artist published books showing images taken all around the world, including an autobiography, two books on migration and refugees, two on African subjects, Kuwait, and the people and landscapes of coffee production. The photograph above is part of Salgado’s last published project, Amazônia, in which he documented the indigenous peoples of the Amazon River basin. Taken in the southeastern part of the basin, members of one of the Xingu River cultures are seen traveling on the river. The beauty of the silhouetted figures, glossy water surface, and misty distance reflects Salgado’s belief that those who still follow their ancestral traditions represent hope that humanity will return to a more intimate connection with nature.

I love living with people, observing communities, and now animals, trees, and rocks too. It is a need that comes from deep inside me. It is the desire to photograph that always drives me to leave again, to go and look elsewhere. Constantly to be taking more new images. – Sebastião Salgado, From my Land to the Planet, 2014

Salgado put his environmental consciousness to work in the founding of Instituto Terra in 1998. Seeing the extreme deforestation which had taken place in Brazil, he and his wife Lélia decided to embark on a large scale reforestation project on the land his father had farmed. In 17 years, the institute managed to reforest over 500 acres which in turn led to the return of many species which had disappeared from the area. Instituto Terra continues its work of reforestation, conservation, and environmental education.

Published in 2013, Salgado’s Genesis photographs also show the artist’s interest in those who still live as their ancestor’s did. In this image, and others from the series, he removed the craftsman from all surroundings, so that nothing distracts us from the person and their action. Throughout his career, Salgado achieved beautiful textures and stunning compositions by combining his commitment to his subject, patience in getting to know the people, animals, and places he wished to photograph, and extraordinary technical mastery.

Photography is a way of life. When you pick up a camera and you look through the viewfinder, you see life in a different way. – Sebastião Salgado

Thank you for reading and subscribing to I Require Art’s Substack. We welcome your questions and comments and hope you’ll share our work to anyone interested. I’ll be back with a new topic next week.

Ive followed Sebastiao Salgado's work for decades. As an X photojournalist, Ive always been intrigued and fascinated by his vision and story telling. I wish I had the chance to meet him and ask him the questions that I think a lot of photographers might wonder and ask. The one Q that came to mind recently was how he survived for months at a time in some of these very difficult environments to not only protect his own health but his Film. I would imagine he had a supply of Tri-X that he keep, but how ? Im also sure he somehow got his exposed rolls shipped out to his labs, but HOW ? in the middle of Rwanda ? Such a treasure and body of work that will be cherished forever and a beacon of our collective condition and memory.

A fine tribute to a great man. His gift for photography was a gift to the world.