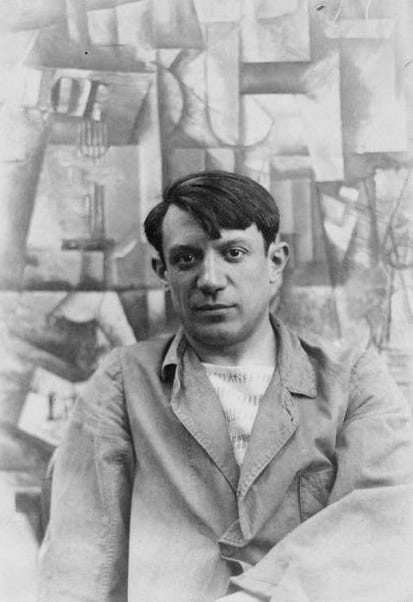

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973) is most closely associated with the Cubism style, despite the variety of styles he used during his long career. In previous editions, I have discussed Picasso’s early career. Now I want to explore the invention of Cubism, which had its origins in the friendship between Picasso and Georges Braque (French, 1882-1963). This relationship developed after Picasso first unveiled Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1907 (see Edition 7). As their friendship grew, Picasso and Braque moved independently toward some aspects of Cubism. Even Les Demoiselles d’Avignon contains fractured forms similar to the later Cubist style. Beginning in 1909, the two artists worked together. Braque later described the artists as “a pair of climbers roped together” and Picasso remembered the two artists visiting one another daily to see what had been achieved when they were parted.

Paul Cézanne was especially influential on Cubism. Picasso and Braque closely studied Cézanne’s paintings when they were displayed in large posthumous exhibitions in Paris in 1907. An important influence was Cézanne’s technique of passage, in which the edges of color planes dissolve into adjacent planes and which destroys the distinction between an object and its surroundings. In Cezanne’s Still Life with Apples and Peaches, this passage technique can be seen in the draped fabric in the center of the composition, especially where it meets the pyramid of fruit. Cubist works use a similar technique to shift from one plane to another. Cézanne abandoned traditional linear perspective and worked with the idea that we alternate between seeing the bigger picture and seeing small details a bit at a time. The artist used these shifts in viewpoint as he worked which led to details like the misaligned table edge and tilted tabletop in this still life.

Picasso and Braque first established Cubism as a rigorous rule-bound study of visual form. This first phase of Cubism has come to be known as Analytical Cubism because the forms in the work are considered analytically from multiple angles of view and then broken into color planes ranging in size from a single brushstroke to the large plane of a wall or table. In Still Life with a Bottle of Rum, the smallest planes are the readily visible brushstrokes, almost pointillist in their independence, while the large planes of the curved table edge are found in the upper and lower right and in the center left edge of the composition. Picasso and Braque, at least partly inspired by Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, were attempting to depict their subjects as seen from different angles in space and at different moments in time. At the heart of Cubism is the idea of deconstructing the subject and its surroundings and reconstructing these into a new non-naturalistic reality. The idea that more than one reality exists had been part of scientific and cultural conversations since the late 19th century, but Cubism was the first 20th century artistic movement to take the position that reality is different from appearance.

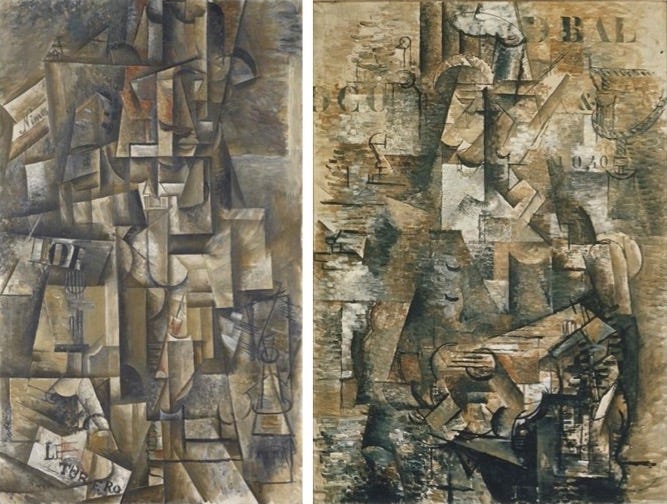

In addition to governing the size and variety of planes, the rules of Analytical Cubism limited the artists’ color palette to neutral tones, often with a golden tint. These two paintings (Picasso’s on the left and Braque’s on the right) only hint that these are human figures, primarily by the facial features at the center near the top. However, guitars are slightly easier to make out, in Braque’s painting near the bottom center and a sound hole and some strings just below the letters OL in Picasso’s painting. By 1911-1912, when these paintings were made, it was almost impossible to identify the painter of Picasso’s and Braque’s works. This was partially intentional; for a short time, the artists even left their names off the fronts of the works. Both of these works are signed only on the back of the canvas. Such anonymity went against the individuality celebrated in Modern art, though, and eventually both resumed signing their works.

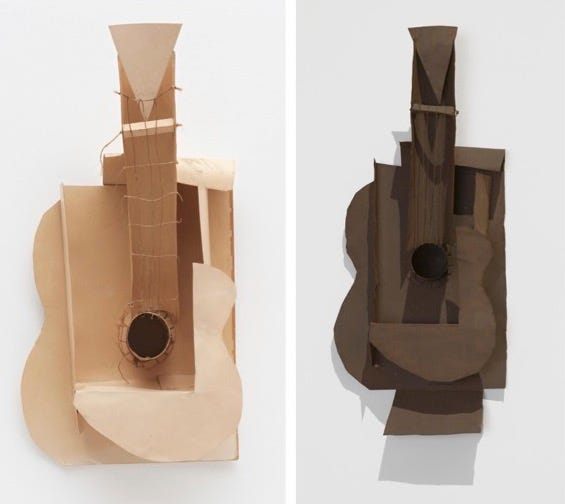

Around 1912, Picasso and Braque began applying their deconstructive approach to the physical world by creating sculptures made from cardboard. Picasso’s Guitar of 1912 is a rare surviving example of these fragile constructions. Using different colors and weights of cardboard and paper, as well as wires and string, the artist has created a fractured image, though one that is far more comprehensible than those found in Analytical Cubist paintings. Two years later Picasso translated his cardboard construction into metal. This approach to sculpture is now known as assemblage, and can be seen as a three dimensional rendition of the basic Cubist theme of reconstructing the artist’s subject into a new multifaceted reality.

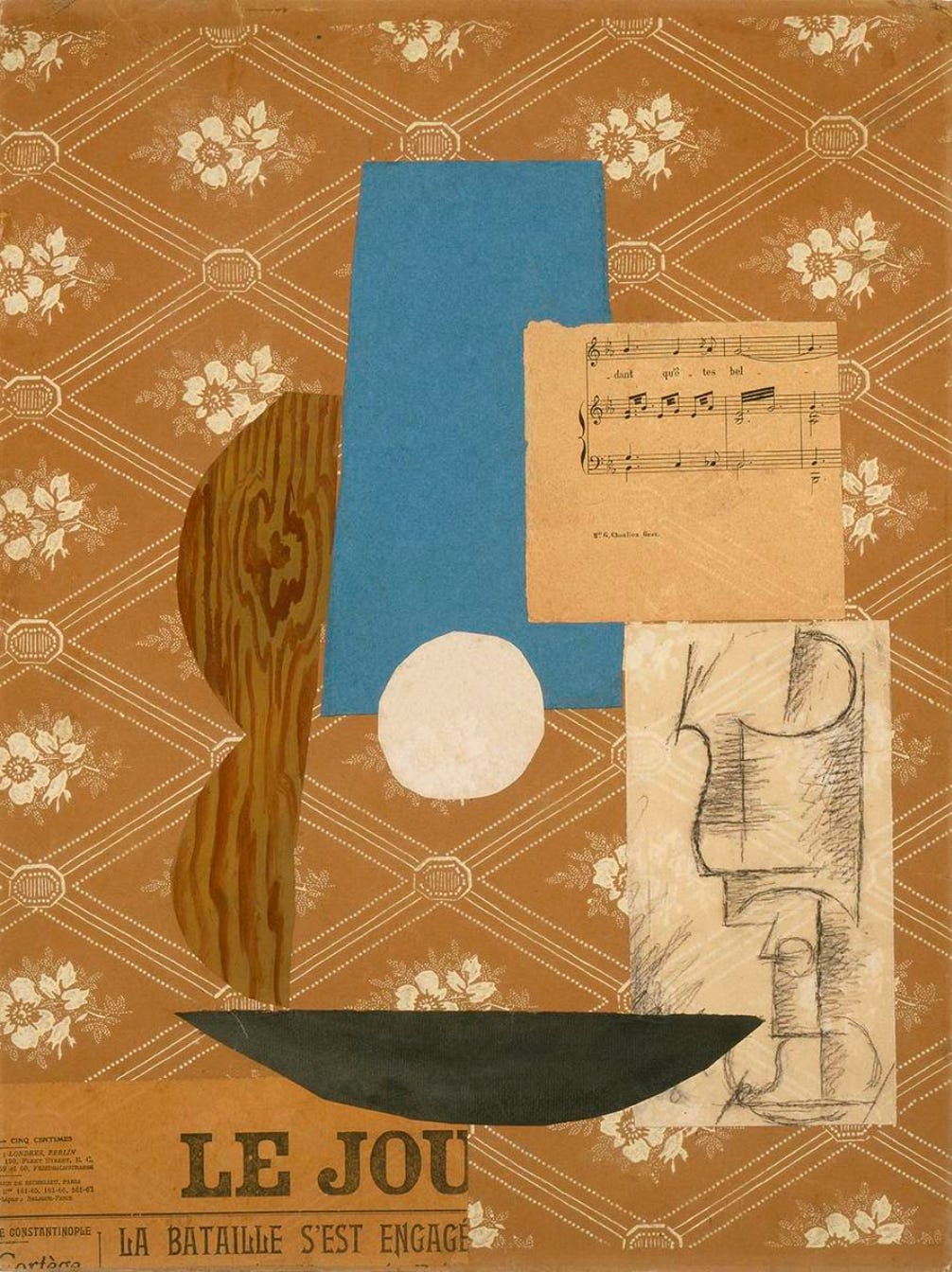

At the same time that the artists were exploring three dimensional Cubism, Picasso and Braque began to experiment with what they termed papiers collés (pasted paper), a form of collage that uses only paper. These works are considered the first use of collage in fine art. In Guitar and Wine Glass by Picasso, we see an excellent example of the Cubists’ approach to collage. Using a sheet of wallpaper as the background, the artist created a guitar from of various papers and added a Cubist-style charcoal drawing of a glass. In addition to the small sheet with the drawing, the paper used in this collage include a fragment of sheet music, colored paper, simulated wood-grain paper, and newspaper. In Analytical Cubist works, stenciled letters and numbers had sometimes been represented (see the paintings above), and in the collages, Picasso frequently applied legible fragments of newspapers to create levels of unexpected meaning. In Guitar and Wine Glass, the newspaper fragment is cut so the masthead’s “Le Journal” has been shortened to “Le Jou.” While recognizing the original word, I am also reminded that jouer is the French word “to play.” In contrast to this lighthearted meaning, the newspaper’s headline says “The Battle Has Begun” while the music fragment includes words and fragments that can be read “beautiful quests.” Thus, this work contains both a playful quality and a sense of seriousness.

Picasso extended the idea of collage to painting in Still Life with Chair Caning. Using a shaped canvas framed with rope, the artist plays with levels of illusion in this work. Cubist still life elements are painted and partially obscure a fragment of oilcloth which is printed with an illusionistic chair caning pattern. Painted elements cast painted shadows over the oilcloth. The letters J-O-U appear again, this time painted and intersecting with a painted fold or edge. Picasso challenges our sense of reality with the real rope, painted newspaper, illusionistic caning, and of course with Cubist fracturing.

Collage had shown Picasso and Braque that they could loosen their Cubist rules and allow greater self-expression while maintaining the philosophy of a restructured reality that was essential to Cubism. Inspired by the larger multicolored and multi-textured shapes in the collages, Picasso and Braque introduced bright color and larger planes into their paintings. Known as Synthetic Cubism, this style is easier for viewers to interpret and allowed the artists to differentiate themselves. Picasso’s The Student looks almost like a collage with its rectangular outlines and areas of flat, bright color.

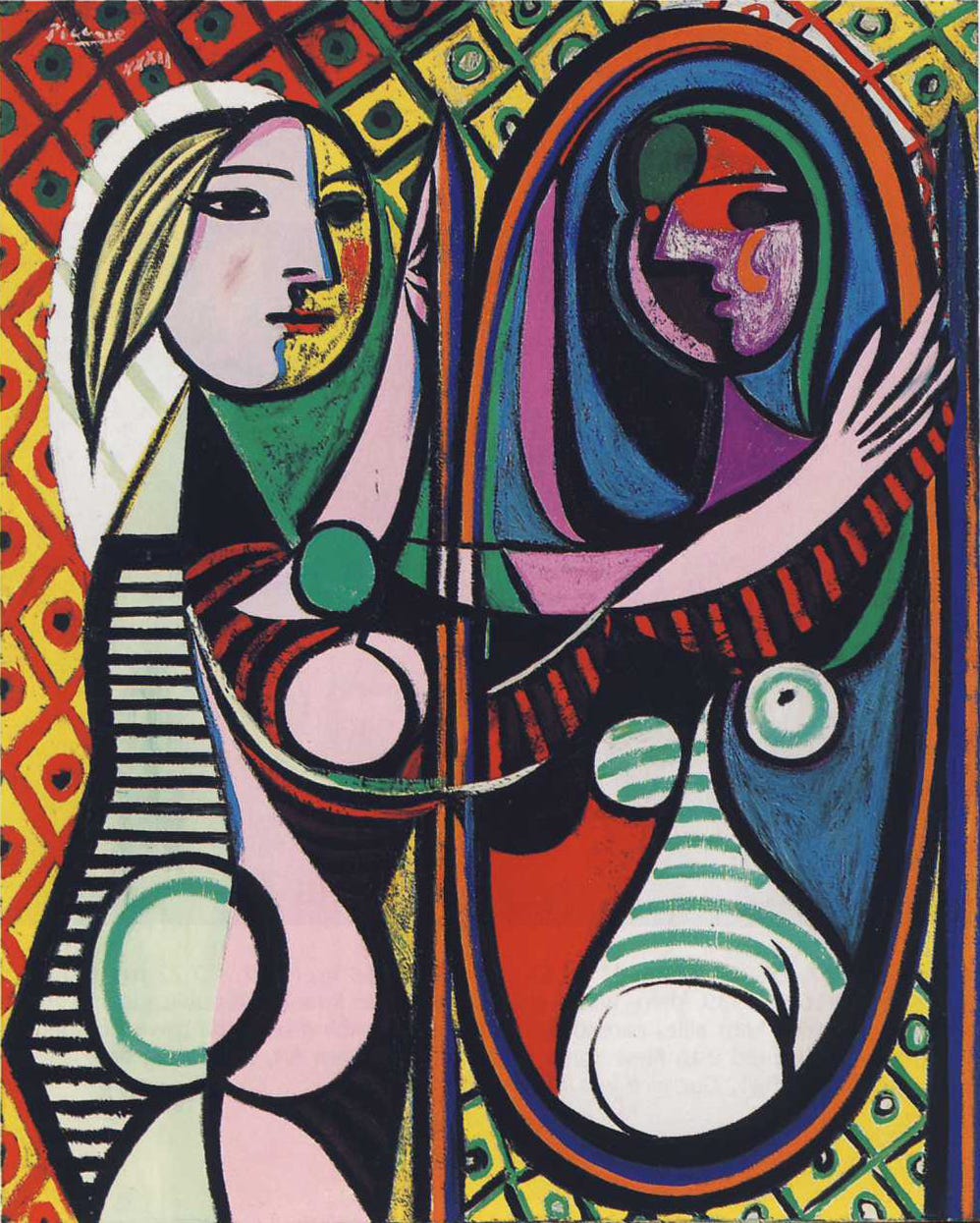

The collaboration between Picasso and Georges Braque was interrupted by the outbreak of World War One. As a French citizen, Braque was called into military service while the Spaniard Picasso remained in Paris. The two artists were never close again, though each continued to work in the Synthetic Cubist style after the war. For Picasso, Cubist distortions and shifting angles of view became only one of his wide-ranging artistic tools. In later works like Girl Before a Mirror, the vivid colors and patterning of Synthetic Cubism are striking, as are Cubist distortions of anatomy. What Picasso has added to the Cubist elements here are Expressionist color in the contrasting brightness of the girl and her reflection and a Surrealist sense that we are seeing a psychological or interior reality rather than visible reality.

This edition is part of our series on Pablo Picasso in honor of the 50th anniversary of the artist’s death. If you missed our previous posts (Editions 3 and 7), please look for them on our Substack page.