In this edition, I’m exploring an early 20th century movement which sought to create art that was uniquely Canadian. The Group of Seven was founded in Toronto in 1920 and disbanded in 1933. The artists hoped to develop a new style based on depictions of the mountainous wilderness which they saw as symbolic of Canada. Bold and colorful compositions expressed their passionate belief that these landscapes reflected the Canadian national character and would be a source of spiritual uplift for both artist and viewer. Early support from the National Gallery of Canada and other patrons, private and public, led to the movement’s success and its rise to a position of prominence in Canadian art.

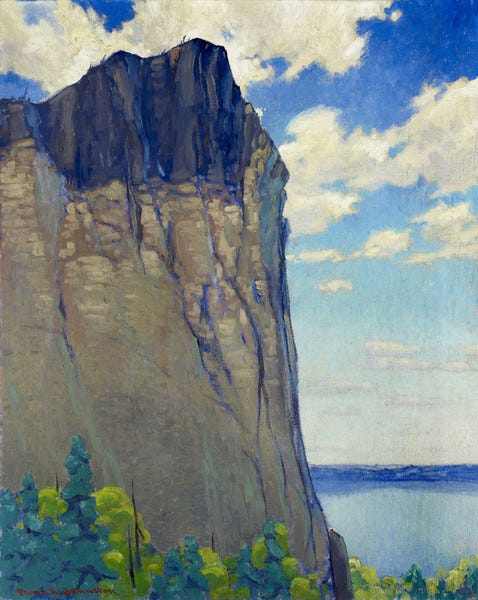

An excellent example of the Group of Seven approach is Frank Johnston’s (1888 – 1949) Where Eagles Soar, which was created about the time of the founding of the movement. The colors are vivid and the form is painterly, with visible brushwork throughout but most apparent in the foliage at the bottom of the work. The warm brown mountain contrasts with the cool blue sky and water and with the vivid green trees. This focal point of the work, a massive, seemingly inaccessible mountain, fits in with the Group of Seven’s emphasis on Canada’s wilderness. Though one of the founding members, Johnston only remained with the Group of Seven for a year. He relocated from Toronto to Winnipeg and exhibited independently for the remainder of his successful career.

The Group of Seven’s origins are found much earlier than the group’s official establishment in 1920. Between 1911 and 1913, men who later helped create the Group of Seven met one another while working at Grip Ltd., a design firm in Toronto. J.E.H. MacDonald (1873 – 1932), head designer at Grip, was an important supporter and organizer of the artists, and an artist in his own right, before and during the establishment of the Group of Seven.

One of the employees MacDonald encouraged at Grip Ltd., was Tom Thomson (1877 – 1917). Though shy and doubtful of his talent, Thomson was inspired to develop beyond his graphic design work and begin painting. He was an enthusiastic fisherman and outdoorsman and his passion for the outdoors was reflected throughout his painting. In 1912, Thomson made his first trip to Algonquin Park in Central Ontario, beginning a five year period of fervent artistic productivity. His works, with their intense color, slight abstraction, and wilderness themes, were extremely influential for all of the artists who became the Group of Seven. However, Thomson’s accidental death while canoeing in 1917 prevented his membership in the group. In his 1964 essay “The Story of the Group of Seven,” member Lawren Harris (1885 – 1970) said that Thomson was “a part of the movement before we pinned a label on it.” To this day, Thomson’s works are discussed and exhibited alongside those of the Group of Seven. Spring Ice of 1915 shows one of Thomson’s favorite themes, a tree or trees silhouetted against a vivid contrasting backdrop. The intensely blue water contrasts with the pale pink, yellow, and green foreground rocks in a way that reminds me of works by Post-Impressionists like Paul Gauguin.

If not for the disruptions caused by World War I, the movement might have formed as early as 1914, perhaps under the name Algonquin School. A.Y. Jackson (1882 – 1974) had studied briefly at the Art Institute of Chicago and in France, where he had contact with Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. In later years, members of the Group of Seven looked to him for inspiration and instruction because of these contacts with European art. In 1915, Jackson enlisted in the Canadian Army, but was wounded early in his deployment. For the remainder of the war, he was employed as a war artist for the Canadian Army. Jackson’s painting Maple and Birches shows that many of the characteristics of the Group of Seven’s style were well established before their 1920 debut. The theme of an uninhabited landscape, a contrast between distant mountains and foreground trees, and visible brushwork are features which would become hallmarks of the Group of Seven.

J. E. H. MacDonald had become friends with Lawren Harris in 1911, after Harris admired MacDonald’s work seen at a small exhibition in Toronto. Their friendship was essential to the formation of the Group of Seven. MacDonald had already begun to articulate the need for a national style or school of art and to encourage his colleagues at Grip Ltd. to expand beyond their commercial art work. Harris, though not associated with Grip, was equally enthusiastic about the goal of a national style, and was able to provide financial support through his own inherited wealth and through his connections to potential patrons.

After Tom Thomson’s death and the conclusion of World War I, the two friends renewed their efforts to develop a national style by organizing sketching trips for themselves and their artist friends. Harris built the Studio Building in Toronto which provided workspaces for his colleagues and financed trips by boxcar to Algoma in northeastern Ontario, a favorite spot of the artists. By 1919, they were calling themselves the Group of Seven and in 1920, organized their first public exhibition under that name. Though the reviews of their work were mixed, mostly due to the artists’ more expressive use of paint and color than was usual in Canadian art at the time, they were recognized as a purely Canadian artistic movement. Such a movement was seen as desirable because it established an artistic identity for Canada as distinct from the British Empire.

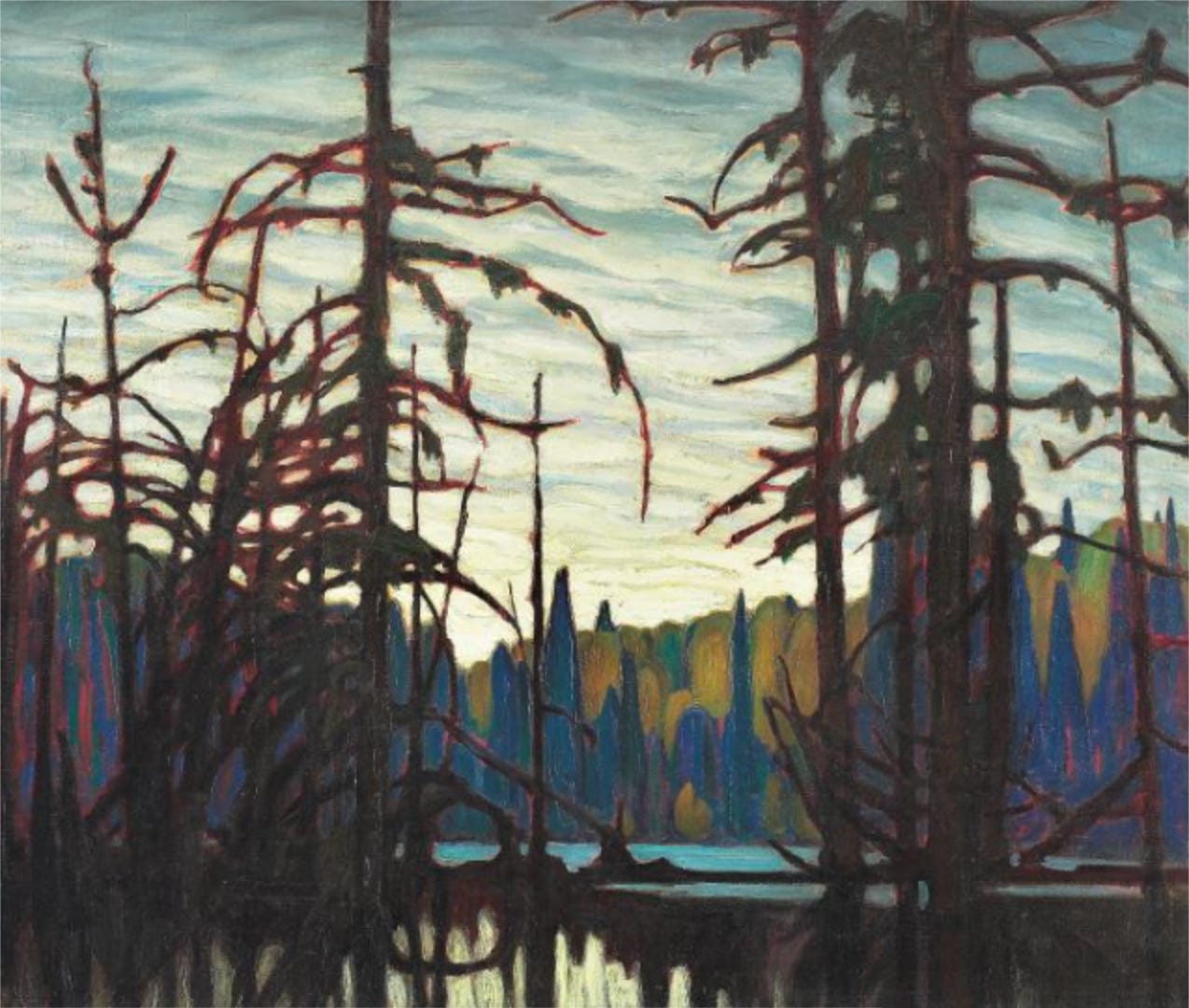

Harris had studied for three years in Germany where he had encountered innovative styles and ideas. His early works, like Beaver Swamp, Algoma, (c. 1920) show the influence of Post-Impressionism, in painterly texture and simplified forms, and of Art Nouveau, in the use of repeated curves. After the breakup of the Group of Seven, Harris turned increasingly toward abstraction, though still inspired by the far northern Canadian landscape. The artist’s late adoption of abstraction calls attention to the fact that European artists, and even some in the United States, had begun exploring pure abstraction before World War I. To some critics and historians, the dominance of the Group of Seven had led to stagnation within Canadian art until the 1950s.

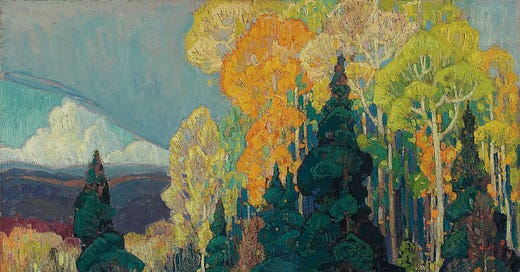

Bold color and a tendency toward simplified contours in Franklin Carmichael’s (1890 – 1945) Autumn Hillside show how the Group of Seven artists turned away from the conservative, highly finished landscape style that was preferred by the Royal Canadian Academy, critics, and buyers at the time. Nearly all of the Group had studied outside Canada, Carmichael in Belgium, and had seen the Post-Impressionist and Art Nouveau styles that dominated European painting in the early 20th century. In this painting thick paint patches are visible throughout the foreground rocks and plants but are also found in the bright autumn foliage of the middleground. That painterly form ties Carmichael to Post-Impressionism, while the fan-like patches of foliage hint at Art Nouveau influence. Incorporating these styles dismayed the conservative taste of the Toronto art establishment, but continued support from Canadian National Gallery director Eric Brown and others allowed the artists to continue on their innovative path.

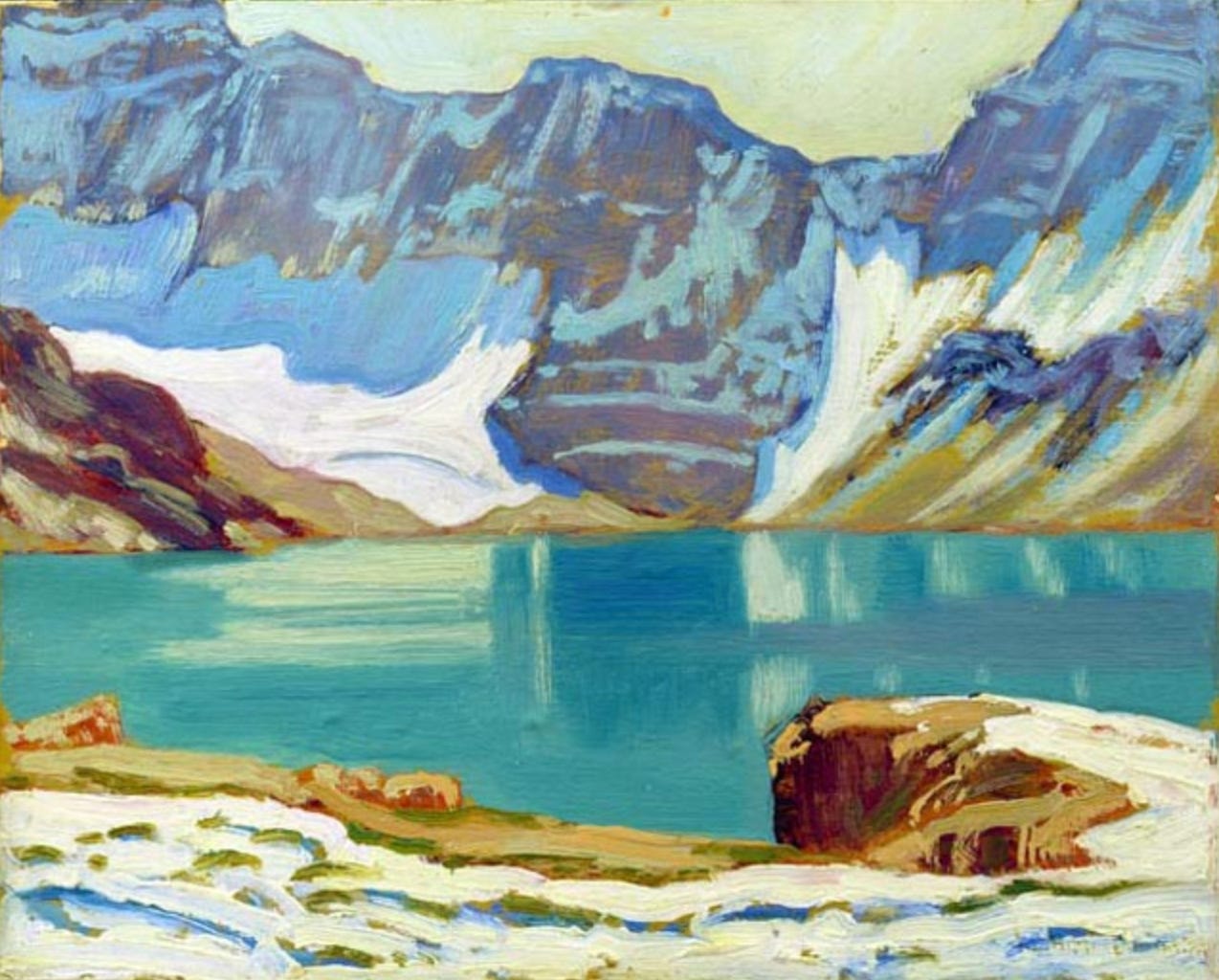

As the 1920s progressed, the artists began to travel further afield. This was in part driven by concerns within the group that they were not truly representative of Canada, either in their subjects or in their membership. How could they claim to be a national art school without artists or subjects from beyond Ontario? A. Y. Jackson was so determined to visit and paint all parts of the Canadian wilderness that he is reported to have created over six thousand paintings. Frank Johnston relocated to Winnipeg in 1921. Later, artists Edwin Holgate, from Montreal, and L. L. FitzGerald, from Winnipeg, were invited to become members of the Group of Seven. In 1924, J. E. H. MacDonald’s travels in British Columbia resulted in Lake McArthur, Yoho Park, a vividly colored painting of a mountain lake that shows how the style that was invented in northern Ontario could be effective in other regions of Canada. This small sketch, with its large visible brushstrokes and block-like reflections in the lake, is as abstract as MacDonald was willing to go.

Another of the original members of the Group of Seven, Frederick Varley (1881 – 1969) was born in England and emigrated to Canada in 1912. Having studied art in England and Belgium, Varley was then employed as a commercial artist at Grip, Ltd., among the organizers of the new art movement. World War One interrupted his career and, like A. Y. Jackson, he was employed as a war artist by the Army. Much of Varley’s work outside of his war paintings, was portraiture; he was the only member of the Group of Seven to focus on that subject. However, he also depicted landscapes like The Cloud, Red Mountain, hardly surprising as that was the preferred theme of the Group of Seven from the beginning. These artists worked to develop the North as a mythic Canadian place akin to the West in the United States. For these artists, the North was an untouched wilderness symbolic of the national character and that is how it appears in most of their works including Varley’s. The artist’s interpretation of the mountain and cloud is more abstract than was seen in earlier works though. This shift toward abstraction disturbed J. E. H. MacDonald and led him to distance himself from Varley and others of the younger artists who were changing their styles in the later 1920s.

Like Varley, Arthur Lismer (1885 – 1969) was born in England and studied art there and in Belgium. It was he who recommended that Varley emigrate to Canada, having preceded him to Toronto and Grip, Ltd. by one year. After several years, Lismer left Toronto for Nova Scotia where he served as the president of the Victoria College of Art in Halifax. There he became fascinated with the dazzle-camouflage painted naval ships. He too was enrolled as an official war artist, focusing mainly on naval subjects. Returning to Toronto in 1919, Lismer participated in the founding of the Group of Seven. In addition to his career as a painter, Lismer was an influential art educator in Canada and internationally.

The early 1930s saw the death of founding member J. E. H. MacDonald and growing criticism that only the small Group of Seven was receiving institutional support and international notice. As a result of these changes and criticisms, the Group of Seven disbanded and in 1933, the Canadian Group of Painters was established. Many former Group of Seven members joined and its first president was Lawren Harris, who had been instrumental in the founding of the earlier group. Eventually the Canadian Group included the majority of Canada’s leading artists and continued functioning until 1967.

Many of the Group of Seven’s artists continued painting in a style based on their earlier Group of Seven works. An example is Arthur Lismer’s Bright Land painted in 1938. The theme of the work, a prominent tree backed by high mountains and an empty lake, was a favorite of Group of Seven artists. Visible brushwork and bright color from Post-Impressionism and the patterned shapes and echoing curves derived from Art Nouveau are reminiscent of Lismer’s and his colleagues earlier works.

The influence and popularity of the Group of Seven continued long after its short life, but that popularity was not without criticism. From early on, outside artists objected to institutional and private patronage being focused on the Group of Seven to the exclusion of others. More recently, the image of Canada as a wide-open wilderness free to all comers which was promulgated by the artists of the movement has been criticized because those lands had been occupied by indigenous occupants for longer than European colonists had been in Canada. The exclusion of women and of minority and marginalized artists has also been pointed out. There were never any female members of the Group of Seven; Emily Carr (Canadian, 1871-1945) was friends with several members, but was never invited to join the Group. Successor groups: Canadian Group of Painters; Beaver Hall Group; Eastern Group of Painters; and Painters Eleven, welcomed women members and were more interested in diverse styles and in subjects beyond the Canadian wilderness.

In spite of these and other efforts, the members of the Group of Seven remain the best known Canadian artists and their approach to landscape painting is still popular. In 1995, Canada Post issued a set of postage stamps representing works by the group and in 2020 another set was issued to celebrate the centennial of the group’s founding. The Group of Seven has been the subject of museum exhibitions regularly in the century since their founding, including 2020’s “100 Years: The Group of Seven and other Voices” at the Art Gallery of Alberta. Recent exhibitions like this one have incorporated indigenous artists and works by artists critical of the Group of Seven’s philosophy, but these artists remain the best known and most popular in Canadian art history.

I have a beautiful jigsaw puzzle, Falls, Montreal River by J.E.H. MacDonald. Thank you for all the background information on the Group of Seven. All peaceful paintings!

I have to agree with Mr. MacDonald, Varley's work was too abstract, but overall, I really enjoyed the paintings almost as much as your commentary.