In this final post of 2023, I’m going to look at works in a variety of media that didn’t fit into the earlier essays in our series on Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881 – 1973). The artist never viewed these efforts as minor or secondary to his other projects and in some cases worked out challenges that he’d encountered in his painting in other media. To me, they exemplify the restless creativity that was an important part of Picasso’s character.

He had a sort of aggressive delight in encountering an obstacle and surmounting it. Difficulty gave him a jumping-off point from which to conquer fresh fields. – Hidalgo Arnéra (printer, Spanish-French, 1922 – 2007)

A group of photographs taken by Gjon Mili (Albanian-American, 1904 – 1984) show Picasso’s playful and experimental side. Mili, an engineer who had developed an interest in stroboscopic and electronic flash photography, was the first to use these techniques to take non-scientific images. Using a slow film speed, Mili photographed Picasso using a bright flashlight to draw in space. The film recorded the moving light but the quick-moving artist in the darkened space was not caught on the film until he remained still at the end of the drawing. Mili and Picasso tried this technique out several times, from simple objects like an apple to larger figures and animals like the bull in this work. The flowing lines that the artist drew with light are familiar from many drawings, prints, and even ceramics that Picasso created throughout his long career.

In 1916, Picasso met Serge Diaghilev, the impresario of the avant-garde Ballets Russes. The next year he traveled to Italy and working with his friend, writer Jean Cocteau (French, 1889 – 1963), completed the stage curtain, sets, and costumes for the ballet Parade set to music by Erik Satie (1866 – 1925). The story that Cocteau set for the ballet was a publicity parade in which various characters attempt to entice the public to an indoor performance. The use of popular entertainment themes for a ballet was as innovative as Satie’s jazz rhythms and Picasso’s combining of Cubism and his recently adopted more naturalistic style. (Chance Encounters 15) The stage curtain was the largest canvas upon which the artist had worked. He created a theatrical stage framed by red curtains and occupied by the Commedia dell’Arte characters Harlequin, acrobats, and performing animals familiar from his Rose Period (1904 – 1906) works. The style convinces us that we are looking at the indoor performance to which the parade is inviting us but its naturalistic style does little to prepare us for the avant-garde ballet about to be performed.

These are two costumes which Picasso devised for Parade. On the left is the male Acrobat’s costume, a leotard embellished with swirling blue shapes and stars. This costume is suitable for both dancing and acrobatics, in contrast to the Cubist-influenced design for the Musician Manager. His body is covered by a sandwich board sign and the character’s head would sit atop the dancer’s head. His violin is reminiscent of cardboard sculptures Picasso had created earlier in his career. (Chance Encounters 11)

Video: Excerpts from the ballet Parade, music by Erik Satie, scenario by Jean Cocteau, sets and costumes by Pablo Picasso, choreography by Leonide Massine; reconstruction of the 1917 original by Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Europa Danse, 2008.

In this video of excerpts from a 2008 performance reconstructing the original 1917 ballet, the Acrobat and his partner appear first. Though the Musician Manager isn’t included in this video, two other Manager characters do appear. The French Manager, looking like a figure from one of Picasso’s Synthetic Cubist painting come to life, appears after the acrobats. He carries a walking stick and a pipe-like horn. He is joined by the American Manager, whose bulky costume incorporates an urban skyline. He carries a megaphone and a title card that says PA-RA-DE. The managers’ costumes must have been extremely awkward for the dancers. The final characters in this excerpt are a schoolgirl, who is one of the few people to show an interest in the performance being advertised, and the horse who is part of the parade.

Unlike many other media, ceramics were not an interest of Picasso’s throughout his career. Instead he became fascinated by the medium while living in Vallauris on the Mediterranean Côte d’Azur in south-eastern France. After visiting ceramics fairs, he began to experiment at the Madoura ceramics workshop. He spent about 15 years creating earthenware objects, from useful plates and pitchers to sculptures. The face that decorates this small pitcher is testament to the artist’s ability to convey a mood with a few fat brushstrokes. When Picasso created objects like this, he declined to use a potter’s wheel. This often gives his vases and pitchers irregularities that remind the viewer that the objects are handmade. The black and brown that decorate the vase have the same flow and facility of the marks found in the artist’s paintings.

Some of those same brushstrokes help define the face a faun on this plate. One of a series of plates with this design, the painting is unique to this piece. The artist would create a plaster matrix with cut or carved elements and clay would be pressed into the matrix to create repetitious pieces. Picasso would then decorate the pieces with variations on the theme. Picasso’s ceramic output is lively and cheerful, which sets it apart from much of his other work. It isn’t stylistically complex, there’s none of the Cubism of his earlier career, and none of the sexuality or voyeurism of his late works is used. This is the artist at play, a reminder of Picasso’s idea that a childlike, impulsive imagination is central to creativity.

It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child. – Picasso

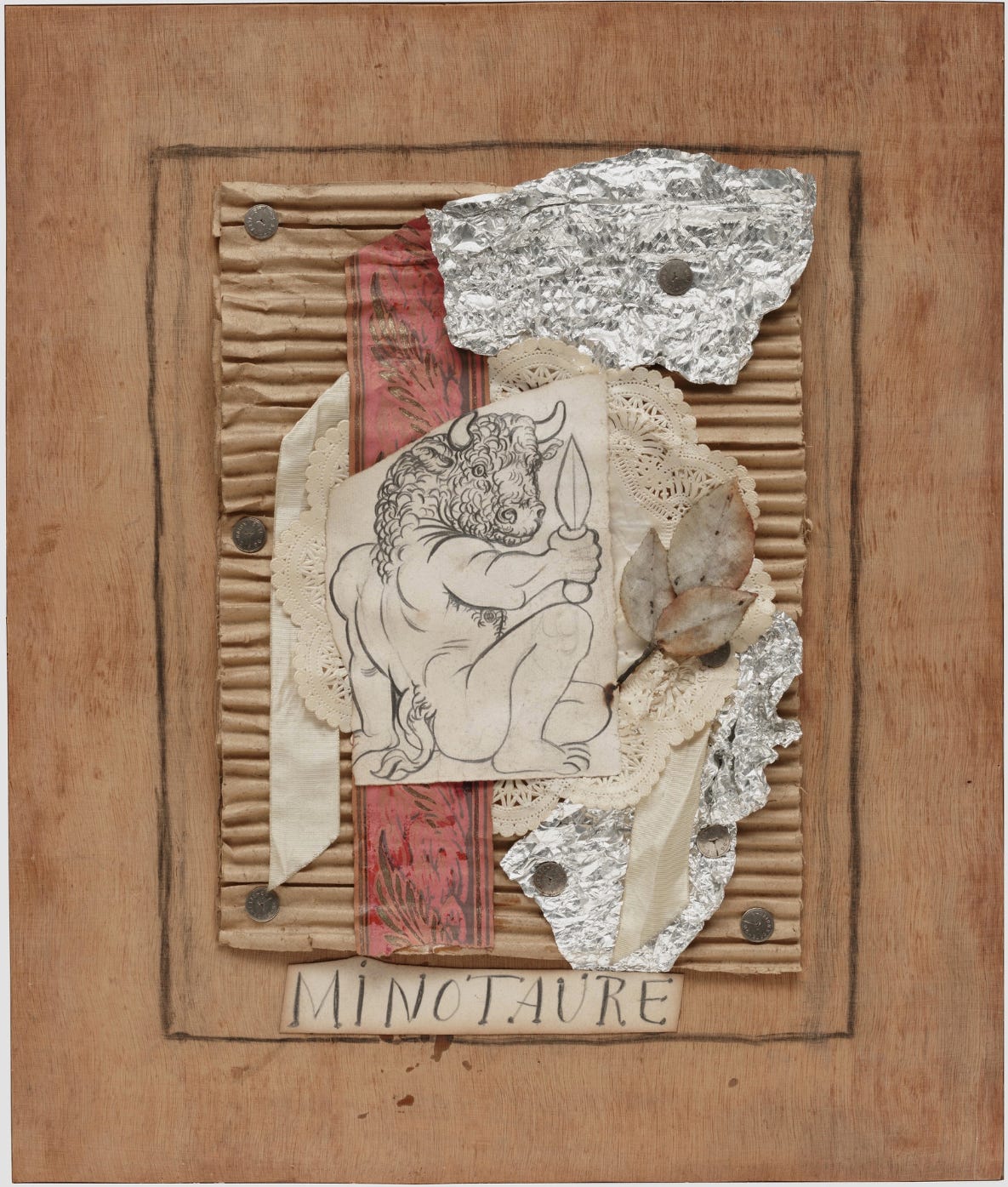

In Chance Encounters 11, I talked about Picasso’s use of collage in connection with the evolution of Cubism. Though he rarely used collage after 1917, he did continue making the three-dimensional equivalent, called assemblage. Above is the maquette (or model) that Picasso made for the journal Minotaure, a Surrealist periodical published in Paris between 1933 and 1939. Picasso’s design for the first issue of the publication incorporates materials that would supply visual textures to the photographic reproduction on the magazine. The materials suit the Surrealist concept of randomness as a trigger for mental freedom. The minotaur, which was to become a powerful symbol for Picasso in his later works, was already an important image for Surrealist artists. The labyrinth in which the beast was trapped symbolized the human mind and the minotaur represented irrational hidden impulses in contrast to the rational mind. Irrationality, like randomness, was seen by the Surrealists as a source of self-knowledge.

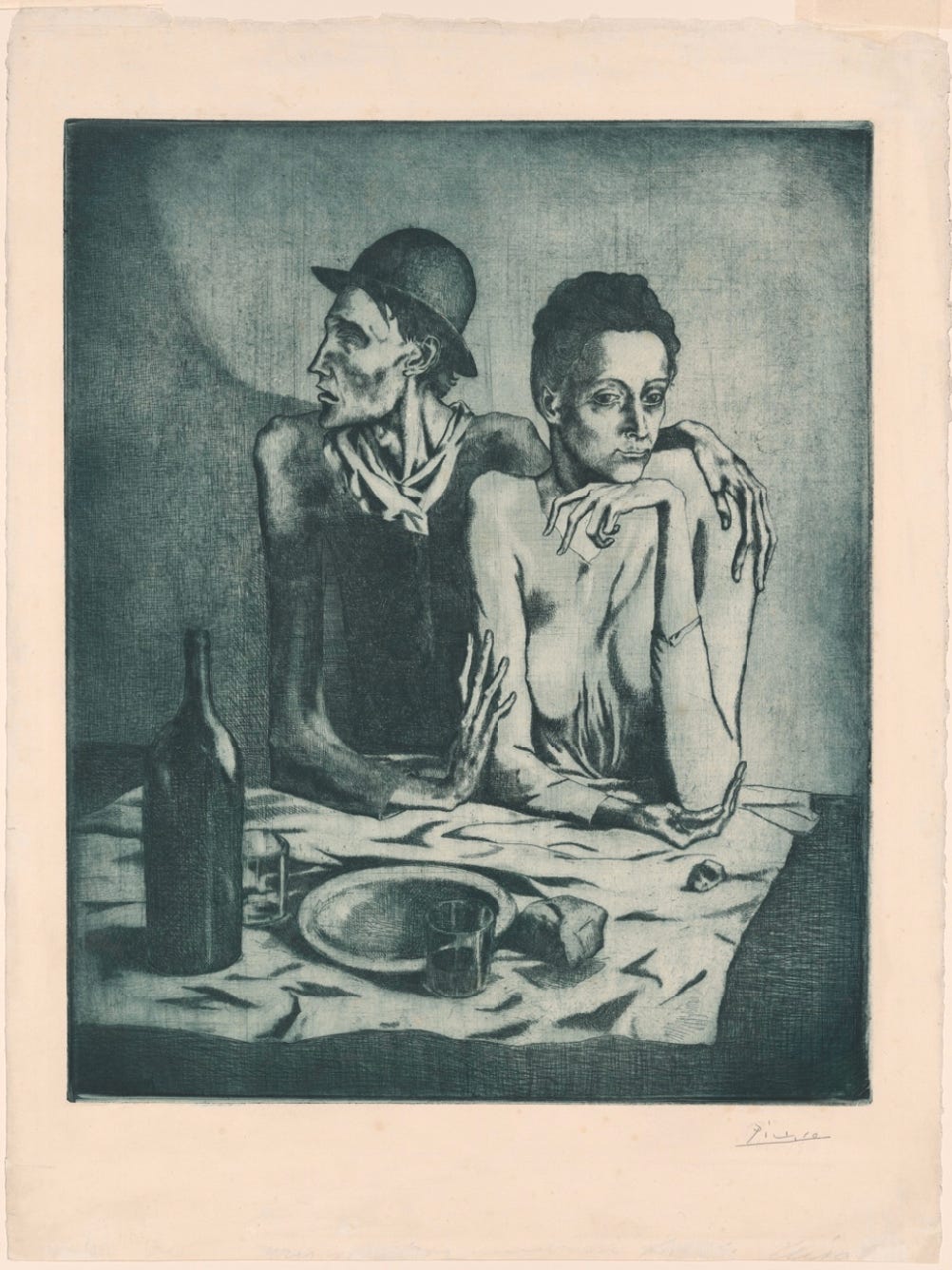

Picasso began making prints very early in his career and eventually he experimented with nearly every means of printmaking. His artistic development can be charted through prints just it can through his paintings. In 1904 – 1905, he created a series of etchings known as the Saltimbanques Suite. The subjects, a blind man and a young woman, are shown as the same elongated, impoverished people who appeared in the Blue Period paintings. It seems likely that the artist created these prints in hopes of earning some money; a single etching plate can create multiple copies so an artist could reproduce a popular design relatively easily. Unfortunately for Picasso, the prints didn’t catch on. Six years later, the dealer Ambroise Vollard (French, 1869 – 1939) discovered them, bought the plates, and created an edition of 250 for each. The edition that Vollard created was printed in black ink. This impression (or copy of a print) in blue-green ink was one of those printed by Picasso in 1904.

In the 1930s, Picasso’s interest in etching was refreshed by his association with printer Roger Lacourière (French, 1892 – 1967). Whenever Picasso collaborated with a new fabricator — a ceramicist, a sculptor, or a printer, he strove to learn all their ideas and techniques, to expand his skills, and then he began to innovate. To create an etching, a metal plate is covered with acid resistant material (the ground) and the artist scratches away the areas intended to hold the ink. After the ground is worked over to the artist’s satisfaction, the plate is dipped into acid. This acid eats away where the artist has scratched the ground away. The ground is then removed and the plate is wiped with ink. The ink remains in the scratched, acid-bitten areas and the plate is pressed against paper, using a printing press to transfer the ink.

Picasso chose to use an extra large etching needle, which would have allowed him to create heavier lines more easily; he also experimented with different materials, including suet and nail polish, to achieve unusual interactions with the acid during the etching process. Minotauromachy (Minotaur Battle) is considered one of the best and most important prints Picasso created in this period. It was never formally published, however; instead Picasso created an edition of 55 which he reserved for close friends and patrons. The photograph that opens this edition shows Picasso at the age of 80 discussing an impression of the Minotauromachy in 1961, almost 30 years after the prints had been executed.

In the print, a young girl confronts a gigantic Minotaur, a hybrid bull-man; she carries flowers and a candle that barely brightens the dark corner in which she stands. A half-nude woman, wounded or dead, lies across a snarling horse. In the window above, two girls and two doves watch; nearby a man looks down from a ladder. There are two popular interpretations of this scene, one personal and one political. According to The Museum of Modern Art website, the artist’s personal life at this time was complicated by his troubled marriage and the pregnancy of his mistress, whose features were similar to the woman on the horse. The minotaur was often a stand-in for the artist in works from the 1930s on, making a personal interpretation reasonable. The political interpretation connects the imagery to the coming Spanish Civil War. The composition of this print contains many echoes in Guernica, Picasso’s masterpiece responding to that war, completed just two years later. (Chance Encounters 15) This is an equally reasonable interpretation and a two layered meaning was well within Picasso’s practice.

After World War Two, Picasso was beset by unwanted visitors at his Paris studio, so he sought refuge at the Paris atelier of lithographer Fernand Mourlot (French, 1895 – 1988). The result was 400 prints created using the lithographic technique, including a series called Le Taureau (The Bull). In lithography, the artist draws on a smooth stone with an oily or waxy crayon. The stone would be treated with acid so that areas not covered by the drawing were more attracted to water. Then the stone would be moistened and an oily ink applied. The ink would only adhere to the drawing, transferring the artist’s marks with great accuracy. Many artists have been drawn to lithography for this accuracy and for the ease of drawing.

He looked, he listened, did the opposite of what he’d learnt — and remarkably it worked! – Fernand Mourlot, lithographer

Picasso was excited by the ability to manipulate the surface of the stone, erasing and revising marks. In the La Taureau series, the artist created 11 different versions of the subject bull using one stone. Each version, called a state, was more abstract than the one before. An edition of fifty was made of each version, except the first of which only a few were printed. In the seventh state above, one can see how Picasso used erased lines to create the abstract structure that overlays the dark bull. Near the center of the bull’s body, a fingerprint is visible. Picasso didn’t just draw and erase on the lithographic stone, he pushed the tusche (the greasy crayon) around with his fingers. That the finished print records such details demonstrates how accurately this technique records the artist’s marks.

In the final state, the bull has become an essence of its original form and we see what aspects of the animal Picasso considered most significant: bulky body, thin legs and tail, penis and curving horns. I am reminded of the simple linear bulls which appear in prehistoric cave paintings at Lascaux and Altamira. These sites were being rediscovered and researched in the years surrounding World War Two and it seems likely that Picasso would have seen photos, drawings, or articles about these discoveries. In some ways, this print is the most abstract image that Picasso ever created.

In the 1950s, after Picasso moved to the Cote d’Azur, access to etching and lithography studios was lacking but he met a local poster printer named Hidalgo Arnéra who introduced the artist to the linoleum cut print technique. In this method, an artist gouges their design into a thin layer of linoleum attached to a wooden block. Ink is applied to the raised area and the image is transferred to paper. Traditionally linocuts required a separate block for each color, but Picasso invented what is now called the “reduction method” in which the block is altered by cutting new areas away after each color was printed. Here again we see the artist learning and then breaking the rules as he had throughout his career. Picasso would work on blocks late into the night and then send them to the printer via his chauffeur. Arnéra would print from the blocks and send the prints back to Picasso by early afternoon the next day. One of the things that attracted Picasso to this printing technique was the availability of a variety of vivid colors which were uncommon in other printing methods at the time. In Still Life with Glass Under the Lamp, color and pattern fill the composition with energy that seems to radiate from the bright light.

From the beginning, Pablo Picasso seems to have been determined to make his mark on the art world and he created thousands of works of art in his quest for fame and significance. Today, he is considered one of the most important artists of the 20th century, if not the most important. His career lasted over seventy years and in that time he mastered nearly every available medium. He influenced artists of his own time and his ideas continue to affect artists 50 years after his death. In this series, I’ve traced Picasso’s artistic development, his innovations, and works both famous and less-known in an effort to demonstrate the breadth of his achievement.

This is the last in I Require Art’s survey of Pablo Picasso’s career in commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of the artist’s death. The previous essays were Editions 3, 7, 11, 15, and 19. If you missed any of these, you can find them by going to our Substack homepage.

This is our last post of 2023. Thank you for subscribing and reading. Our first edition of 2024 will appear on Saturday, January 6. Best wishes for a happy new year.