Happy New Year! Welcome to I Require Art. This our second year of publishing Chance Encounters and Viewing Rooms here on Substack. If you’re a new reader, I hope you’ll check out our archive and if you’ve read my work before, thanks for your continuing support. In this edition, I’m discussing Fauvism, the last style developed in response to the theories of Impressionism and the first artistic movement to appear in 20th century European art.

Imagine yourself as a fashionable Parisian in 1905. You’re excited to visit the Salon d’Automne, just the third outing of an art exhibition known for presenting younger artists, and art that is new, unusual … and scandalous! You wander through retrospectives in honor of famous deceased artists Neoclassicist J.A.D. Ingres and Realist Édouard Manet and begin to wonder what all the fuss is about. You catch sight of a pretty, almost Classical sculpture and think that you’ve fallen for overblown advertising. As you enter the gallery where the sculpture is displayed you are startled, even shocked, by the bright colors, bold brushstrokes, and unfinished quality of the works hanging on the walls nearby. Depending on your mindset, you are thrilled by the controversy swirling around these innovative painters or you are offended by the “chromatic madness” and “pictorial aberration” on display.

Restaurant de la Machine at Bougival by Maurice de Vlaminck (French, 1876-1958) was one of the paintings that shocked visitors to that Salon d’Automne. Even today, it’s easy to understand why visitors to the exhibition were so shocked. Though the objects are recognizable, none are depicted as they really look. The colors seem to have been squeezed right out of the tube and the haphazard brushstrokes suggest the artist had no plan before he applied them. Is it any wonder that critics used terms like madness, childishness, and anarchy about such paintings?

I wanted to express myself without troubling what painting was like before me. — Maurice de Vlaminck

The juxtaposition of paintings like Vlaminck’s with a delicately carved, naturalistic sculpture inspired the art critic Louis Vauxcelles (French, 1870-1943) to proclaim that the sculpture was “Donatello parmi les fauves (Donatello among the wild beasts).” Vauxcelles was a friend and supporter of Henri Matisse (French, 1869-1954) whose work was also in that shocking gallery. It seems likely that Vauxcelles was just being ironic about the combination of works but once the term fauves appeared in print, opponents of the new style latched onto it. The artists themselves, realizing that the publicity was good for their careers, happily adopted the term.

The characteristics most often identified in Fauvism are

autonomy of color, that is, arbitrary color not connected to nature. This is the foremost requirement and was seen as the distinguishing feature at the time. It was also something seen in European art for the first time since the Renaissance of the 1400s.

light and shadow rendered by contrast of hue (color) rather than tone (lightness and darkness)

a sense of spontaneity or lack of planning in the design or composition

no rules for technique in applying paint

a cheerful, celebratory mood

and the individuality of each artist’s response to their subject. Fauve paintings are records of the artist’s experience of looking at and then reinterpreting the visible world.

Though the Fauve style was new to critics, the artists had been developing it for several years. Luxe, Calme, et Volupté by Matisse had already been exhibited in Spring 1905, half a year before the Salon d’Automne. The work had been recognized as a new variant of Neo-Impressionism, the pointillist style of Georges Seurat (French, 1859-1891) and Paul Signac (French, 1863-1935) and liberal critics like Louis Vauxcelles were excited about the direction Matisse appeared to be taking.

Though Matisse was in his mid 30s, he was just beginning his career as an artist. He had studied law and was working as a court administrator when he became ill, necessitating a lengthy convalescence. To help him pass the time, his mother bought him art supplies and he discovered what he described as “a kind of paradise.” It was 1889 and he abandoned his law career in favor of painting. After encountering Impressionism and the Post-Impressionism of Vincent van Gogh’s (Dutch, 1859-1890), Matisse began to incorporate newer ideas, especially more vivid color. Matisse was developing his artistic ideas rapidly and his style was changing often in the last decade of the 19th century and the first years of the 20th century.

Painted a year or so after Luxe, Calme, et Volupté, Matisse’s Girl Reading has more in common with Vlaminck’s Restaurant de la Machine than with his own earlier painting. The obvious connection to Neo-Impressionism has gone. Instead Matisse and Vlaminck vary the application of paint in highly individual ways. Vlaminck replaced traditional variations of light and shadow to indicate depth with variations in brushwork, a dotted texture in the middle ground and thick strokes in the foreground, both contrasting with the blocks of smoother color on the distant buildings. Matisse’s approach to brushwork is less programmatic. Other than the diagonal edge of the table, nothing suggests depth. There are areas of pointillist dots on the table and in the flowers above the girl. Small patches of color define objects in the lower right corner as well as the girl herself. Larger patches of color fill the area above and to the right of the girl, but almost none of these depict recognizable objects or describe spatial relationships. Matisse demonstrates his response to the scene and his belief that color can create pictorial space without reference to appearances.

Many of the artists associated with Fauvism were students together in the studio of Gustave Moreau (French, 1826-1898). Moreau was a Symbolist painter, creating mysterious, naturalistic images based on myth and literature, but unlike his contemporaries, he didn’t enforce his own ideas on his students. Matisse said of Moreau as a teacher

He did not set us on the right roads, but off the roads. He disturbed our complacency. — Henri Matisse

Like Matisse, Charles Camoin (French, 1879-1965) studied with Moreau. An important characteristic of Fauvism is the independence of the artists; each was free to apply the ideas of Fauvism according to their own desires. Charles Camoin’s palette in Artist in Her Studio is very similar to Matisse’s in Girl Reading. The arrangement and application of those colors is very different however. Camoin organized his picture into blocks of color, with the dark shape of the painter standing out against the brighter shapes surrounding her. The subject of this painting is Camoin’s Fauve colleague and friend Émilie Charmy (French, 1878-1974). Though the male artists of the group receive the most attention, there were several women who participated in Fauve exhibitions. Two of Charmy’s still life paintings were included in the momentous 1905 Salon d’Automne.

Another woman who participated in Fauvism was Swiss artist Alice Bailly (1872-1938). After studying in Switzerland and Germany, Bailly moved to Paris in 1904. She was drawn to Fauvism for its intense colors, unrealistic space, and the emphasis on individuality. The latter she had found sorely lacking in her academic studies. Bailly’s Pink Garden demonstrates her personal style which included darker outlines and a tilted ground plane, but her palette has Fauve brightness and non-naturalistic color. Like most Fauve artists, Bailly moved away from the movement in the next decade, becoming skilled at the Cubist style introduced by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. (For more on Cubism, see Chance Encounters 11: Picasso: The Cubist Revolution)

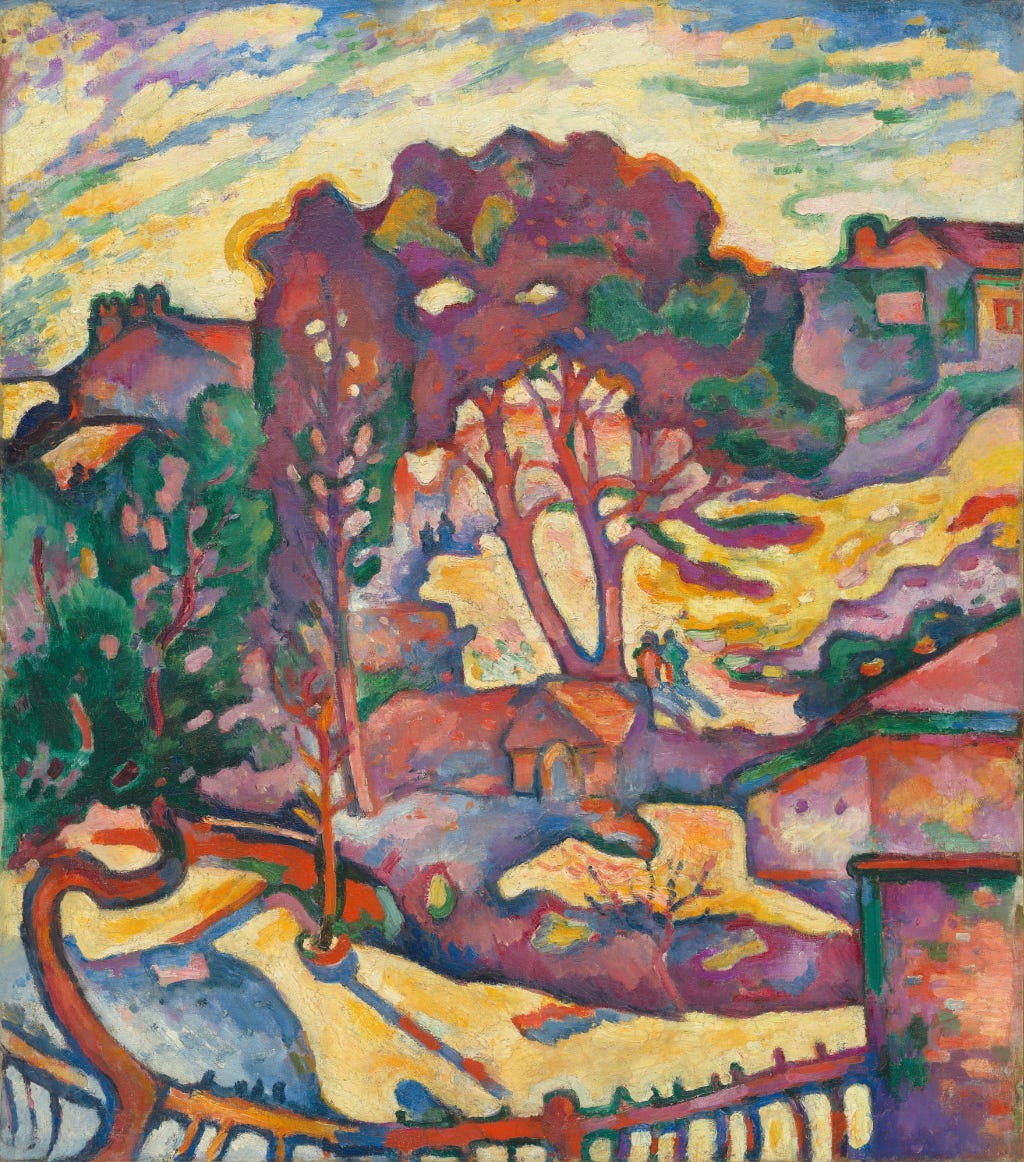

One of the founding artists of Cubism, Georges Braque (French, 1882-1963), passed through a Fauvist stage in his career. Braque was one of a small group of artists from Le Havre who embraced the Fauve style after 1905. In Braque’s painting of trees at L’Estaque, the artist maintains some traditional techniques of depth illusion, especially using lighter (higher value) colors to represent the fall of light. On the other hand, few colors are true to nature and each color appears in patches throughout the composition. This approach to color connects the different parts of the design to one another. The same year that this work was created, Braque was deeply affected by a Paul Cézanne retrospective and began to introduce more block-like color patches and geometric design elements which would evolve into Cubism.

Another Fauve from the Le Havre group is Raoul Dufy (French, 1877-1953). Encountering Matisse’s Luxe, Calme, et Volupté at the spring 1905 exhibition was transformative for Dufy. He introduced non-naturalistic bright color and simplified objects into his works. In Jeanne Among Flowers, the flowers and plant forms which are confined to the vase at the bottom of the composition seem to float free in the upper part of the canvas and create a frame for the young girl. As with other Fauve artists, Dufy moved away from the style under the influence of Cubism, but in his mature style he returned to the bright colors of his Fauve period. In those late works the artist defined figures and objects in a sketchy, linear form before filling the canvas with masses of vivid color.

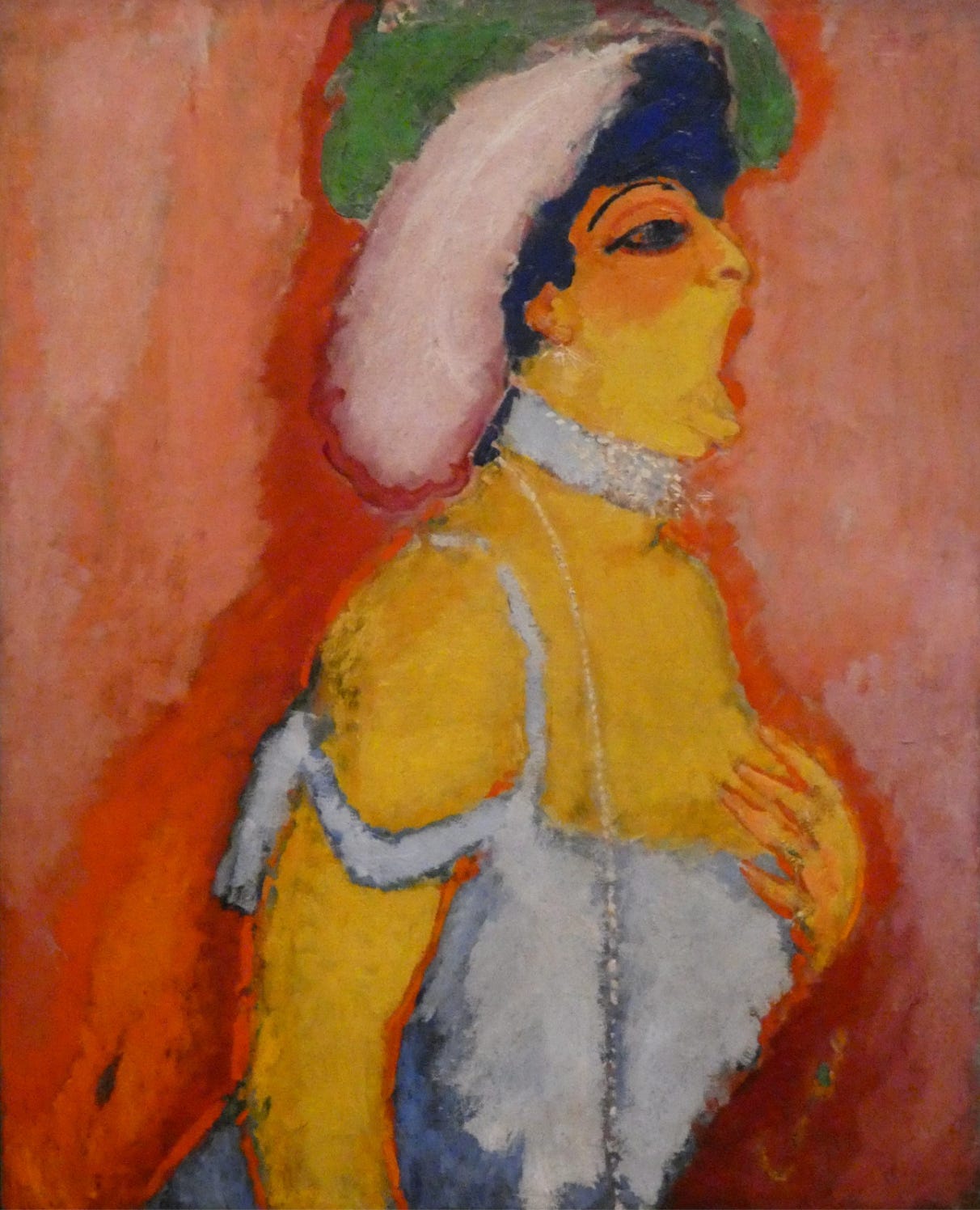

No artist used color more boldly than Dutch-born Kees van Dongen (Dutch-French, 1877-1968). His work was also included in the important 1905 Salon d’Automne. Though many of his Fauve colleagues chose subjects like landscapes, domestic scenes, and portraits, themes which had been made popular by the 19th century Impressionists, van Dongen devoted many of his paintings to the vibrant nightlife of Paris. He was especially known for his colorful images of women, of which Modjesko, Soprano Singer is one of the boldest. The vivid peach and orange background is more like an aura produced by the performer’s voice and personality and her golden skin seems incandescent. The subject of the painting is Claude Modjesko, an African-American drag performer, whose stage names were “Black Patti” and “Patti Créole.” Her act was popular but in a way which paralleled that of the avant garde artists; too many came to jeer and laugh at a performer whose racial and drag identities shocked traditionalists. After World War I, Van Dongen became a fashionable portraitist, a surprising turn for the bohemian artist of the early years of the century.

André Derain (French, 1880-1954) was the third founder of the Fauve movement alongside Henri Matisse and Maurice de Vlaminck. While training to be an engineer, Derain took some painting lessons where he encountered Matisse. Then Derain’s chance meeting with Vlaminck, on a train that derailed, led the two to set up a shared studio at Chatou, west of Paris. Wishing to abandon his engineering studies, Derain brought Matisse, clad in a respectable suit and accompanied by his wife, to meet his parents so they could see that not all artists were wild bohemians. With their agreement, he began to study painting. Derain’s portrait of Matisse was one of the shocking paintings in the 1905 Salon d’Automne.

In spite of the controversy, there were critics, patrons, and dealers who supported the Fauvists. The dealer Ambroise Vollard, who also supported Pablo Picasso at this time, proposed that Derain visit London in 1906 to paint. Vollard was inspired by earlier London paintings executed around the turn of the century by Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926). Those had been a critical and financial success and Vollard hoped for a similar result. London Bridge is one of the 30 paintings Derain created during his two month stay. The work is pure Fauvism with its splotchy orange sky, green and yellow river, and deep blue buildings. The colors, river traffic, and crowded bridge create a sense of urban energy quite different from earlier artists’ depictions of the city. Later in life Derain recalled the Fauve period

It was the era of photography. This may have influenced us and played a part in our reaction against anything resembling a snapshot of life. No matter how far we moved away from things, it was never far enough. Colors became charges of dynamite. — André Derain

The first artistic movement to arise in 20th century Paris, Fauvism acted as a transition from the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist avant garde styles of the 19th century to the radically modern styles of the 20th century. Though contemporary critics found the style shocking, Fauvism was the last Post-Impressionist style and usually followed Impressionism’s lead in subject matter, the use of painterly form, and a stress on individual subjectivity. Of the other Post-Impressionist styles, the most influential for Fauvism were Neo-Impressionism, as mentioned above, and Vincent Van Gogh. A 1901 exhibition of Van Gogh’s works came as a revelation to young artists because so few of Van Gogh’s paintings had been available for public viewing before this.

Fauvism was a short-lived movement. The various artists had been developing the style during the first years of the 20th century before the first public notice of their efforts in 1905. They hadn’t considered a name for their group until Louis Vauxcelles’ clever word-play. Called Fauves from 1905 on, the artists continued to create their explosions of color for just a few more years. By 1911 though, nearly all of the artists had moved on to new ideas and Fauvism was over. Most of the artists regarded it as style of their youth, something to outgrow as they matured. Several artists shifted to the next “new thing,” Cubism. Others incorporated ideas from Fauvism into the more emotionally intense Expressionism movement. Following World War I, Derain and Vlaminck both renounced Fauve colors for the more restrained and naturalistic style movement known as the Return to Order (Retour á l’ordre). As for Matisse, he carved his own path, using color to create an expressive style all his own.

The Kunstmuseum Basel in Switzerland is presenting a large exhibition of Fauvism, “Matisse, Derain, and Friends: The Paris Avantgarde 1904 – 1908,” through January 21, 2024. Some of the paintings included in this edition are part of that exhibition, as indicated in their captions.

This is truly well done and outstanding. I’d say it’s the best piece of work I’ve read in months and thoroughly explains Fauvism above and beyond. I knew a good amount of the artists but wow, some I’ve never heard of here which I plan to explore further today you’ve made them so alluring and the accompanying works for them are a true salute. You did them well. I can’t thank you enough.

Congratulations on entering year 2 with this wonderful post, which rings in the New Year in the best possible way.