Women artists in the mid-20th century found it much harder to gain access to galleries and publicity than their male colleagues. Only recently have they begun to receive some of the attention they should have received at the time. I’ve selected a group of woman working in a variety of media to give a sense of the diverse abstract practices in use in the middle of the 20th century. The artists featured in this edition are currently included in the exhibition “Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction, 1950-1970” at Turner Contemporary in Margate, UK, through May 6, 2024.

This video shows many of the works included in this exhibition. I focus on a selection below.

The oldest and most famous of the artists in this edition, Louise Nevelson (American, 1899 – 1988) is considered one of the most important American sculptors of the 20th century. In spite of her later success and current fame, in the 1940s Nevelson was a victim of the period’s disregard for the seriousness of women artists. One anecdote claims that a critic said of a 1941 exhibition that they became aware at the last minute that the artist was a woman, fortunately preventing them from declaring her a great sculptor among modern artists. Nevelson herself never accepted the label feminist, feeling that she, and anyone else, could succeed even in the face of such narrow-mindedness. Commenting on Nevelson’s success, Dan Bacigalupi, a former director of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, said

In Nevelson's case, she was the most ferocious artist there was. She was the most determined, the most forceful, the most difficult. She just forced her way in. And so that was one way to do it, but not all women chose to, or could take, that route. – Dan Bacigalupi

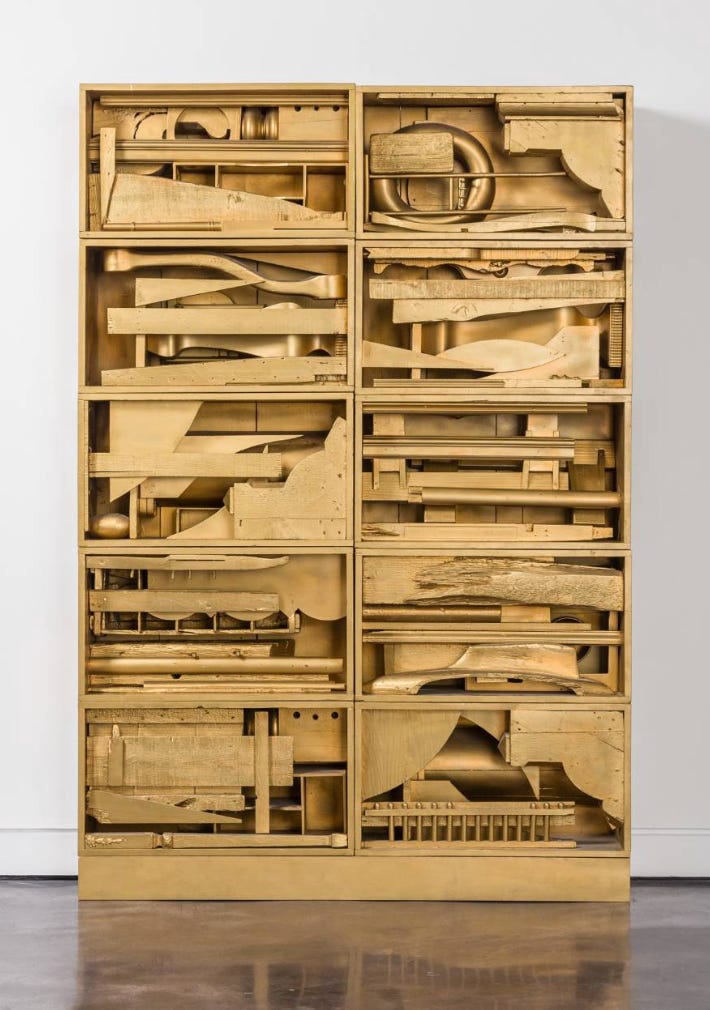

Nevelson experimented with painting and printmaking and with a variety of styles and subjects in her early years. She received some critical approval, but little financial success in those years. The artist created her first found wood sculptures when she was 55 years old. She collected discarded wooden objects on city streets, beginning in her own neighborhood which was scheduled for redevelopment. Nevelson organized fragments of architectural wood and furniture, as well as bits of raw wood, in rectangular units and then combined these boxes into large scale arrangements. These could range from small pieces to be hung to the wall-like structures she called “environments.” To unify the diverse elements in her sculptures, the artist painted the works a uniform color, at first using only black, later creating white or gold sculptures. To Nevelson, black signified aristocratic greatness and white was dawn and emotional promise. Gold referred to the mythical idea that America’s streets were paved with gold and the artist described gold-painted works like Royal Tide III as part of her “baroque phase.” The Baroque period of art history was the 17th century and was characterized by luxurious excess and intensely dramatic art. The metallic, reflective finish of Royal Tide III suggests luxury while the repetitive, layered horizontal elements add the complexity for which Baroque period architecture is known.

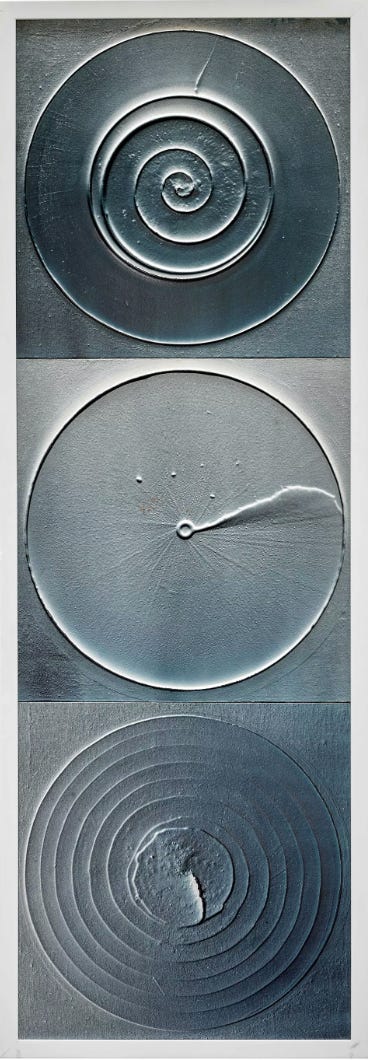

Another artist who utilizes a modular system to create sculptures ranging from small wall hangings to wall-sized arrangements is Yuko Nasaka (Japanese, b. 1938). Nasaka began painting at age three and progressed to oil painting in her early teens. She attended an Osaka high school noted for producing fine artists whose example the young artist sought to emulate. While attending a women’s university for a home economics program, Nasaka turned to an art club to make progress in her career. She began to create cast metal reliefs and turned away from painting because it lacked the concrete physicality of sculpture. In 1962 she was one of the few women inducted into the Gutai Art Association, the primary group of abstractionists in Japan. Nasaka was a member of Gutai Phase Two; this younger group was more interested in industrialization and Japan’s burgeoning technological growth compared to the older generation’s focus on responding to the effects of World War Two on Japan. In Nasaka’s mature style, she employs innovative materials and techniques to produce unusual relief compositions. The artist begins with a square wooden panel which she covers with a layer of glue, plaster and clay. Placing the panel on a mechanical turntable, she uses a palette knife and other tools to shape a circular relief in the soft upper layer. Once dried, the panel is spray painted with an automotive finish. Nasaka’s untitled work of 1962 is made up of three of these panels painted silver. The smooth metallic finish helps to create the appearance of perfection from a distance but when looking closer, the viewer discovers variations in texture and small imperfections created by the artisanal process of shaping the soft surface before it dries. The three panels in this example demonstrates the artist’s ability to create varied effects while using the same materials and methods. Even Nasaka’s wall-sized works demonstrate this kind of variety.

In the 20th century, new materials developed at an astounding rate and artists were quick to adopt anything they could get their hands on. Marta Pan (Hungarian-born French, 1923 – 2008) was fascinated by the various plastics being developed in the mid-20th century. She created sculptures for public spaces as well as smaller works for indoor display. Balance, symmetry, and geometry were Pan’s goals in her works. Cylinder 5 (104) from 1968 was fashioned from plexiglass (Perspex) by an industrial fabricator according to the artist’s design. The use of a fabricator ensured that the work would have a perfectly smooth surface and precisely shaped form. This small object, only 5.5 inches (14 cm) in diameter, is almost jewel like in its clarity and interaction with light. In this work Pan was exploring the transparency and optical properties of plexiglass. The sculpture consists of two cones placed together with their points opposite one another. Three pyramidal recesses of different sizes are cut into the interior. These appear and disappear as the viewer moves around the work. Pan is one of many mid-20th century artists, male and female, who utilized new materials to alter our perceptions of space, light, and color.

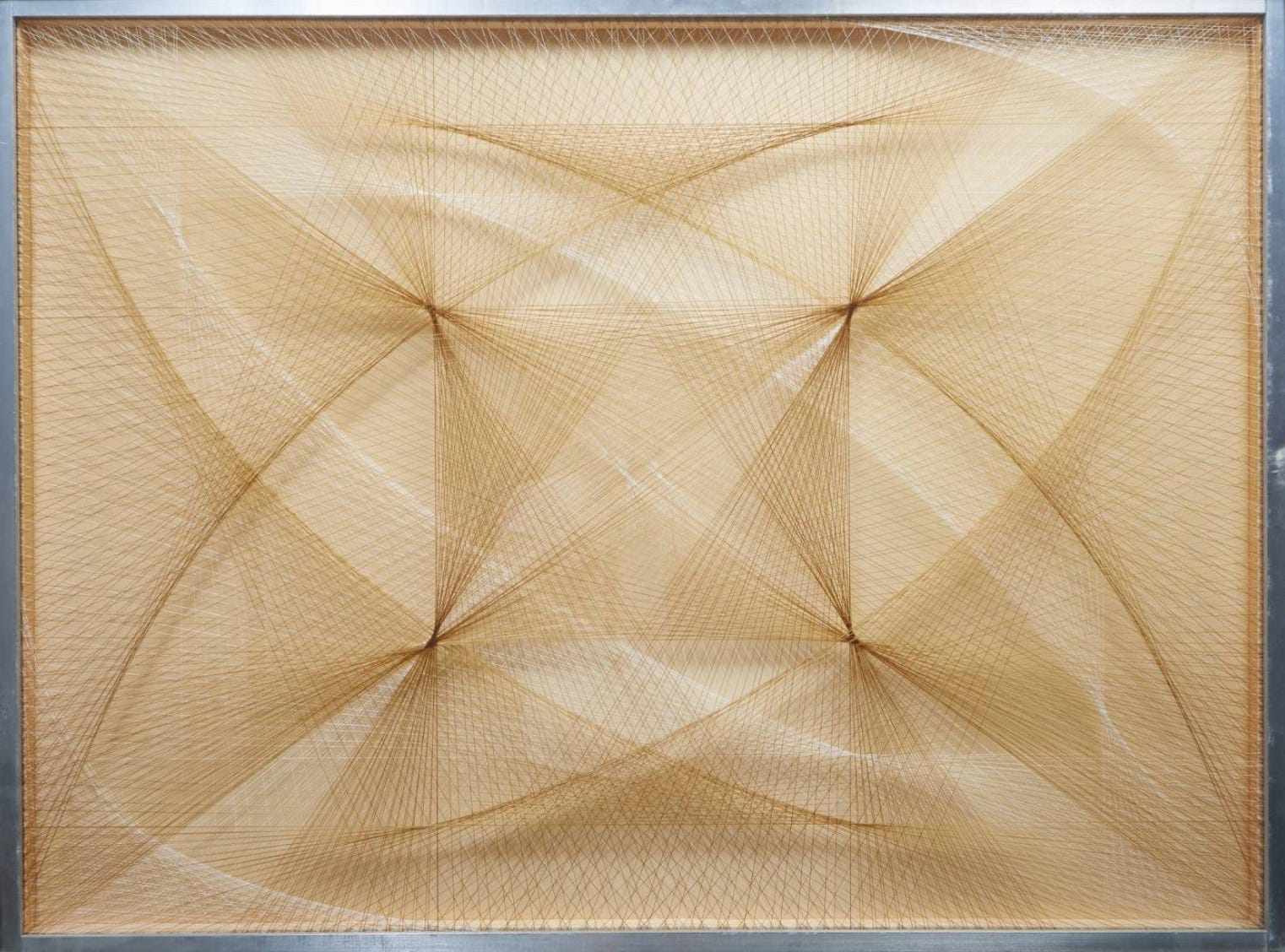

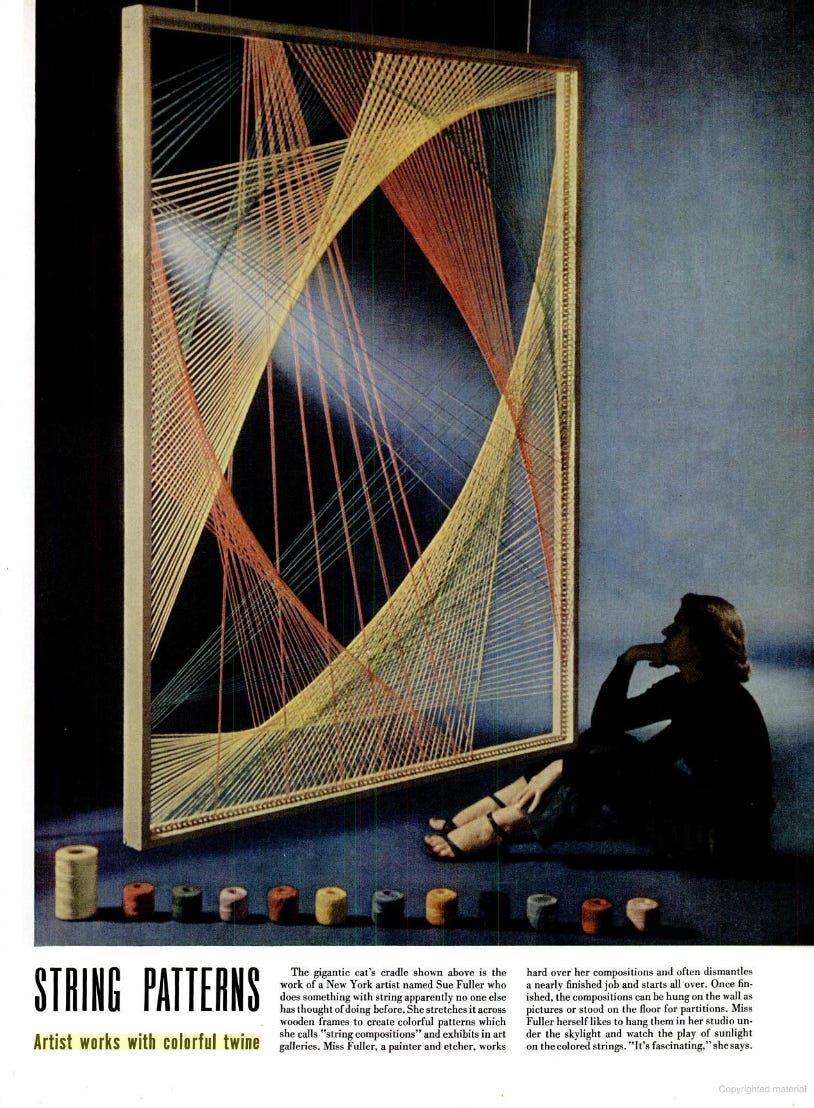

Sue Fuller (American, 1914 – 2006) was also interested in the interaction of her works with space, light, and color. She is also one of many women artists working at the intersection of art and traditionally female crafts. In the 1930s and 40s, Fuller studied with three of the most prominent modernist artists – Hans Hofmann, Stanley Hayter, and Josef Albers. She worked first as a printmaker, eventually beginning to incorporate textiles and threads into her printing process. It was a short step to her innovative use of thread to create elaborate patterns, apparently floating free of any support. Fuller’s mother was an avid knitter and crocheter during the artist’s childhood, leading the artist to feel her work with threads was somehow destined. In String Composition #82, Fuller stretched thread around a nearly invisible aluminum frame and backed the work with silk. In the 1950s, Fuller became concerned with the permanence and preservation of her works, leading her to use synthetic monofilaments and experimenting with new display methods. She also developed and patented her unique methods of using Lucite and other plastics to encase her thread compositions.

Fuller’s work was featured in the October 31, 1949 issue of LIFE Magazine (above). The text below the photograph says

STRING PATTERNS: Artist works with colorful twine. The gigantic cat’s cradle shown above is the work of a New York artist named Sue Fuller who does something with string apparently no one else has thought of doing before. She stretches it across wooden frames to create colorful patterns which she calls “string compositions” and exhibits in arts galleries. Miss Fuller, a painter and etcher, works hard over her compositions and often dismantles a nearly finished job and starts all over. Once finished, the compositions can be hung on the wall as pictures or stood on the floor for partitions. Miss Fuller herself likes to hang them in her studio under the skylight and watch the play of sunlight on the colored strings. “It’s fascinating,” she says.

In the mid-20th century, fiber arts were growing in popularity with women artists often in association with rising Feminist art movements around the world. In spite of this popularity, they were not as valued by museums, galleries, and critics as traditional media. Maria Teresa Chojnacka (Polish, 1931 – 2023) emerged as a working artist in the mid-1960s using sisal and other materials with weaving techniques to create sculptures. For Polish artists like Chojnacka and Magdalena Abakanwicz (1930 – 2017), working with the less prestigious fiber arts allowed them to escape the limitations placed on artists by the Communist regime in their country. Chojnacka’s Chains is composed of three gatherings of strings of interlocking sisal links, knotted at the top and, as displayed at Turner Contemporary, hanging against a wall and spread along the floor. The work can be arranged as the owner wishes however. The rough texture of the material and the way the artist wove the chain shapes into the sisal are all visible. The title refers subtly to the restraint of freedom caused by chains, a symbolic theme of great importance to artists like Chojnacka.

Another artist who weaves her materials together to create chain-like forms is Ruth Asawa (American, 1926 – 2013). However, her material is wire which she bends and weaves into interlocking forms which she hangs so that they can interact with the light and space they occupy. Asawa created her wire sculptures at home while raising six children. When completed, her sculptures were hung in and around the artist’s home allowing her to live with them and experience study the way their shapes, textures and shadows responded to one another. Hanging Two-Sectioned, Open Windows Form is constructed of wire bent into repetitive E-shapes. The openness of the woven wire makes the work seem almost weightless and, as is the case with all of Asawa’s works, they project fascinating shadows that respond to any air movement.

I was interested in [wire] because of the economy of a line, making something in space, enclosing it without blocking it out. It’s still transparent. I realized that if I was going to make these forms, which interlock and interweave, it can only be done with a line because a line can go anywhere. – Ruth Asawa

Another craft-related technique seen in the Turner Contemporary exhibition is ceramics. Daniela Vinopalová (Czech, 1928 - 2017) worked clay into shapes that originated in her imagination. In spite of the title Sculpture-Vase, the work is neither a useful nor a decorative vase. Instead, the artist shaped a roughly human figure and distorted and gouged into it to create the finished sculpture. The work retains a few facial features, including a gold-accented eye, and is ornamented with a band of glazing but otherwise resembles something like weathered rock or eroded surface.

Through my work I try to look for a certain order, which I believe is built up of many contradictions, sometimes even of incomprehensible nonsense, but in its totality, it forms a whole that creates a balance between the contraries that hold it together. – Daniela Vinopalová

Vinopalová had her first solo show in Prague in 1966 and by the next year was considered a top sculptor in the city. In 1968, she began to receive some international attention, but that was the year when the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia to repress the political liberalization and democratization of the Prague Spring. Vinopalová was forced to stop creating her abstract sculptures; she was threatened with expulsion from national arts organizations if she did not. In that period, the artist accepted a few public commissions, but mostly created jewelry. Vinopalová was unable to create artworks according to her own vision until the fall of the Communist regimes. She had her first post-Communist exhibition in 1996.

Though the Turner Contemporary exhibition focuses on sculpture, there are some paintings and other two dimensional works included. This painting was created by Habuba Farah (Brazilian, b. 1931), the child of Lebanese immigrants to Brazil. Farah became interested in art by the age of 12 but took the more practical path of becoming a secondary school geography teacher. She taught for eight years before stepping away to commit to a career as a visual artist. Beginning in the 1950s, the artist explored color theory, using the ideas of Michel Eugène Chevreul, the 19th century scientist whose color theory also inspired the Impressionists and Neo-Impressionists at the end of the earlier century. Farah combined her study of color gradations with a love of geometric patterns. In the 1970s she corresponded with Victor Vasarely, the Hungarian-French painter who worked with optical illusions and is considered a founding artist of the Op Art movement. In works like Untitled from 1972, we see Farah using the lessons she’d learned about geometry and color to suggest a green landscape lit by golden sunlight while maintaining a strict geometric structure. The artist is now in her 90s but continues to create paintings that synthesize geometric structures with light and atmosphere.

Women artists today have many more opportunities and face many fewer barriers to participation in the art world than their predecessors experienced. Mid-20th century women like the artists discussed above were as innovative in materials and form as their male colleagues. They deserve the recognition that can be achieved through exhibitions like “Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction 1950 – 1970” at Turner Contemporary. You can find a list of artists in the exhibition here: "Beyond Form" exhibition link. The small number I’ve included in this edition are only the tip of an iceberg of creativity and innovation.

Thank you for reading. I’ll be back with a new topic next Saturday.

Wonderful post, once again. Nevelson (whose work is definitely brilliant) is the only artist you write about with whom I’m familiar, which might itself serve as a commentary on how undersung the work of these artists is. Thank you so much for bringing these artists and the exhibit to my attention. A cornucopia of rich and varied art to explore.

I really liked the "big string" by Fuller.