Today is the 150th running of The Kentucky Derby, so I decided to look for some horse and horse racing imagery to honor the occasion. I’ve lived in Central Kentucky for over 30 years and the horse breeding and racing industries are enormously important in this area. The lives of humans and horses have been intertwined for millennia and humans have recorded the appearance and behavior of horses since some of the earliest known art. Horses are important subjects in the prehistoric cave paintings of Lascaux (Link to Lascaux Cave website) and they appear in the art of cultures around the world to the present day.

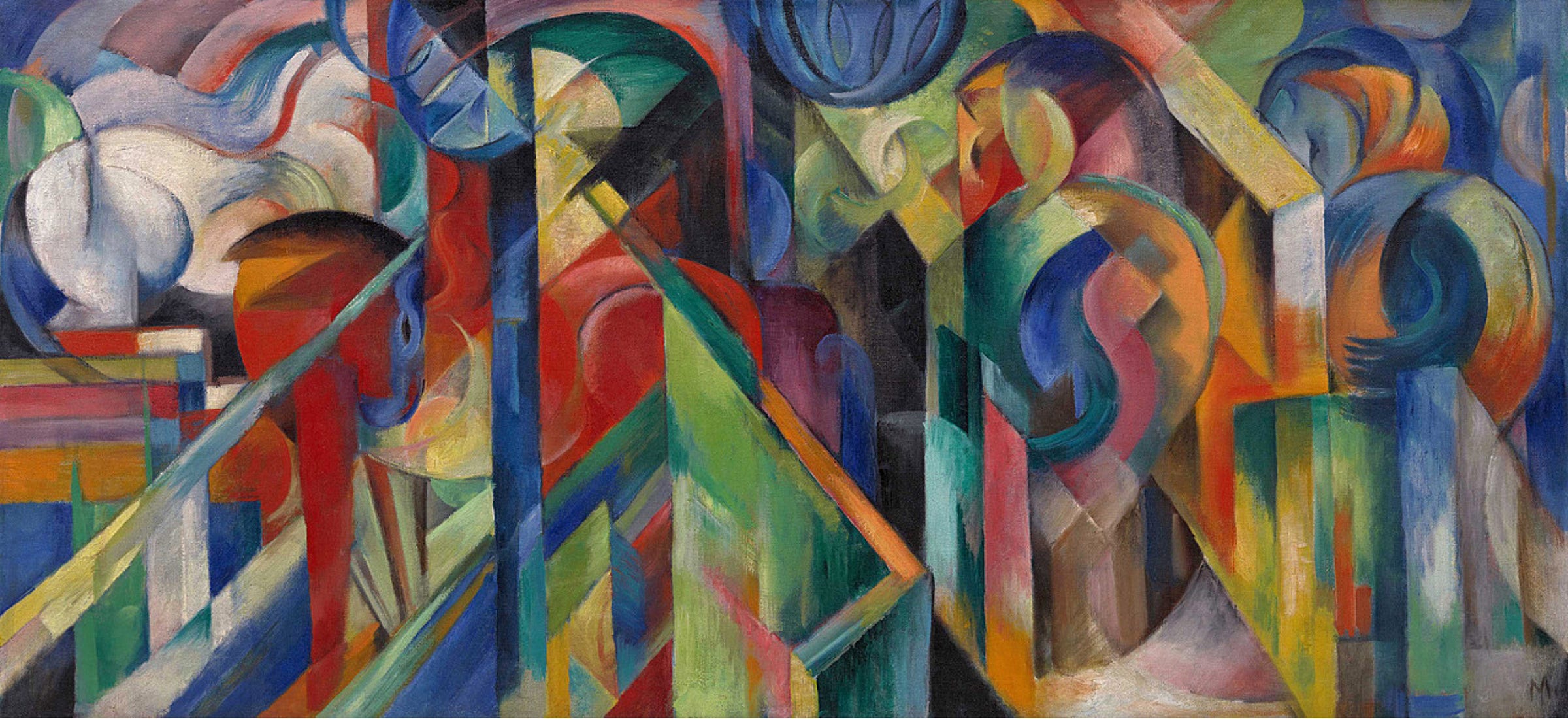

We begin our day at the races in the stables, as depicted by Franz Marc (German, 1880-1916). An Expressionist painter who founded the Munich group The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter) with Wassily Kandinsky, Marc is known for his vivid colors and a passion for depicting animals. In his early years, he even supported himself teaching animal anatomy to artists. In keeping with the Expressionist philosophy, Marc conveys his emotions through the appearance of his works. The movement didn’t require any particular approach from its members. Each was to find their own personal style, but in general, Expressionist artists distorted or abstracted appearances and used bright, usually non-naturalistic, color. These artists believed art had the power to change society, the viewer, or both. Developing in Germany in the decade before World War One, they saw much that needed changing. Tragically, Marc was killed in 1916 in the Battle of Verdun of that war.

Marc believed that animals retained a godly quality that humans had lost. Horses were a favorite theme, most notably in The Great Blue Horses, 1911, in the collection of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. Stables was his last painting on the subject and his most abstract treatment of it. What strikes me about this work is that Marc confined these horses in the stable; he usually represented horses out in open fields. This choice allowed him to mix his beloved animals with architectural details in a cubistic approach. The artist had visited Paris in 1912 where he encountered the work of the Futurists and Robert Delaunay, themselves influenced by Cubism. Many of his works of 1913 and 1914 share Stables’ spear-like forms and fractured shapes, including The Fate of the Animals (1913, Kunstmuseum Basel) and The Bewitched Mill (1913, Art Institute of Chicago). (See Paul Jones’ essay on the latter painting on our Substack: Franz Marc's Bewitching Mill). According to the Guggenheim’s website, there are five horses in Stables but I have to admit that I’ve only found four: a white one facing right, a red one facing left, and two multicolored, facing away at the right. Across the composition, at over 5 feet wide one of Marc’s largest paintings, patches of color repeat and echo one another, moving the viewer’s attention through the work. In keeping with the artist’s view of horses, the animals remain calm within the riot of color and shape.

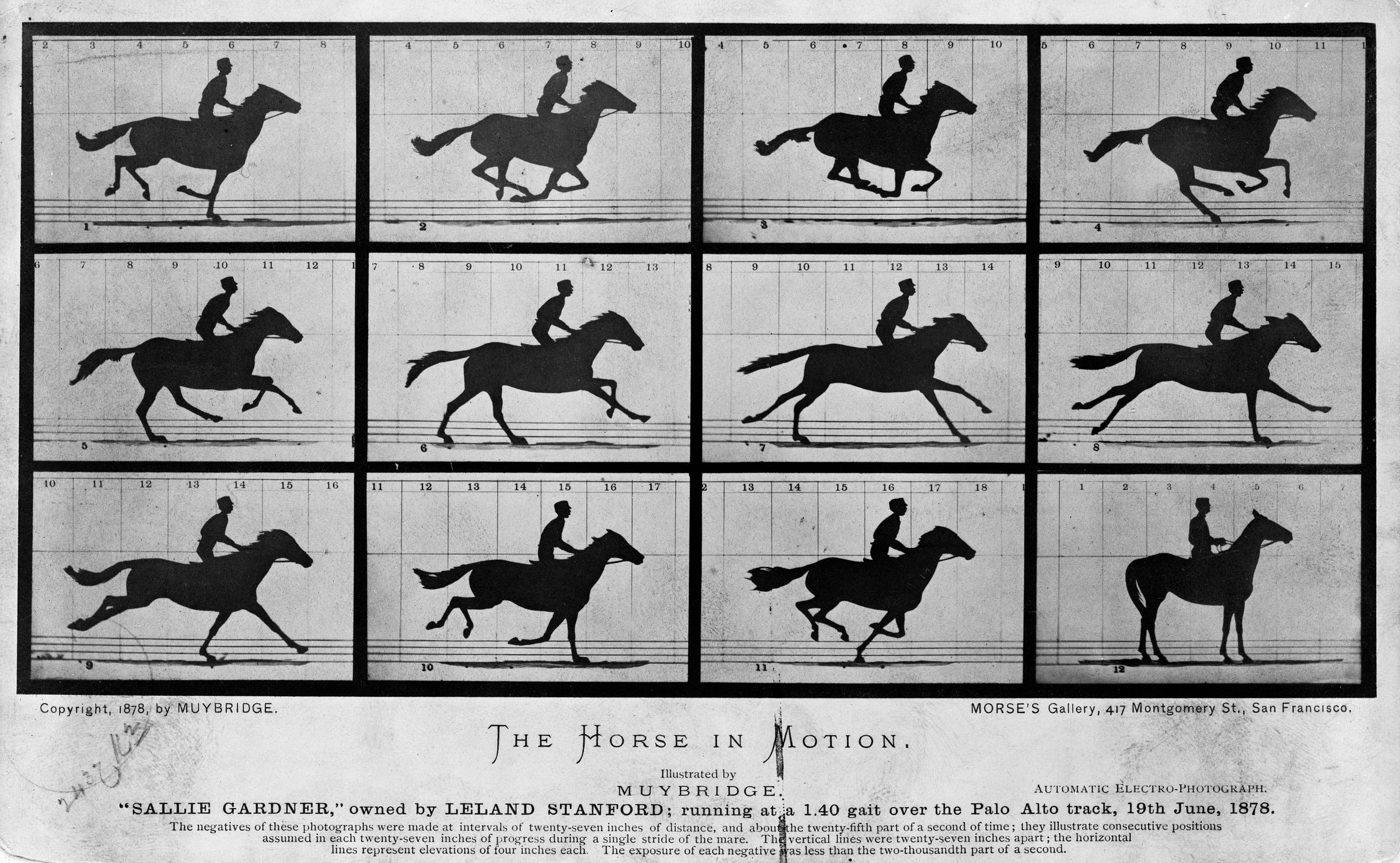

Our next stop is the track, where we will see a horse gallop. In 1872, the English photographer Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) was hired by Leland Stanford (American, 1824-1893), former governor of California and racehorse owner, to capture his home and possessions, including his horse Occident. One of Stanford’s goals was to capture the horse in a trot and gallop, movements too fast for the human eye to capture. European and American artists had usually represented a trotting horse with one foot on the ground and galloping horses with all four legs outstretched and off the ground. Early photography could not capture rapid movement clearly though and the photographer and his patron embarked on a series of experiments over several years that resulted in the images above. This small object is called a cabinet card, a photographic version of the calling card or the modern business card. Working with engineers and technicians from the Central Pacific Railroad (of which Stanford was a founding director), Muybridge developed quicker shutters and electrical triggering devices. He also experimented with more sensitive photographic emulsions. To create the photographs of the horse Sallie Gardner at a gallop, Muybridge set up an array of 12 cameras along the stretch of a race track, each to be triggered by a string as the horse ran through. A back wall, painted white, was marked at intervals so the distance could be seen. A galloping horse had now been photographed, demonstrating that all four feet DID lift off the ground, but when gathered beneath the horse, as seen in the third frame of the first row of the cabinet card, rather than outstretched as artists had depicted in the past. When painters and printmakers took note of Muybridge’s discover and tried to introduce this accurate form of depicting a galloping horse, many viewers disliked the images which looked “wrong” after so many years of the traditional method of depicting horses. The artist went on to photograph motion studies of many animals, including clothed and nude humans, and to share these in Animal Locomotion, published in 1887 in association with the University of Pennsylvania.

Turning now to a very different approach to capturing the dynamic movement of a running horse, we have the bronze sculpture Horse by Raymond Duchamp-Villon (French, 1876-1918). Another talented artist whose life was ended by World War I, he succumbed to typhoid fever contracted while serving as a medical aide. Duchamp-Villon was a member of a very artistic family; two of his brothers and a sister were also successful and famous artists: Jacques Villon (1875-1963); Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968); and Suzanne Duchamp-Crotti (1889-1963). Though his siblings worked in other media, Duchamp-Villon focused on sculpture, continuing working even while serving during the war. Horse is considered his masterpiece, though it was only executed in plaster at his untimely death. As he had hoped to do himself, his artist brothers arranged for the sculpture to be cast in bronze in the early 1930s. Duchamp-Villon was interested in moving sculpture from a naturalistic approach to one which was more formal and stylized. This sculpture evolved from a series of sketches the artist created, progressing from observational likeness to the final abstract sculpture. The artist had studied the anatomy and movement of horses during his service in the cavalry and he is known to have studied Muybridge’s photographic motion studies too. Formed from a variety of geometric shapes, the work seems to be a hybrid of machine and animal. The smooth surfaces suggest the machine aesthetic of the Futurism movement, but the rounded shapes hark back to a horse’s extended neck and the directional thrust of the work speaks of the speed and power of a horse in motion.

A more naturalistic and narrative approach is taken by the great Impressionist painter Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917). (For more about Degas and Impressionism, see Chance Encounters 5 and Chance Encounters 30.) At The Races is one of a number of horse race-themed works that the artist created in the 1860s and 1870s. Visiting racecourses had become highly fashionable in Paris in the late 19th century; the wealthy bourgeoisie (the artist’s own class) traveled out of the city to nearby sites to watch the races in imitation of the British aristocracy. A similar fad appeared in the same era in the United States, among wealthy industrialists like Leland Stanford; the first Kentucky Derby was run in 1875. At the Races depicts a country racetrack with amateur jockeys atop their horses in the middleground. In the foreground, and cut off by the right side of the composition, are a top-hatted gentleman seen from the back and a carriage containing a woman wearing a fancy hat. The deliberately awkward cropping of these elements is used by Degas to indicate that this is a random moment of modern life. Degas had trained with the traditional masters of the French Academy of Fine Arts and his early ambition had been to become a history painter, that is, one who created large works of historical, religious, and mythological themes with moral messages. Influenced by the changing philosophy of art at the time, Degas shifted his goal to recording contemporary life with the dignity and seriousness of a history painter. The artist’s horse racing paintings can be seen as a modern take on the tradition of painting military horsemen and cavalry battles. The horses and jockeys on right side of the canvas sit casually atop their standing and walking mounts, but the horse entering the scene from the left is moving fast and being reined in by its rider. This pair draws our attention to a detail in the distant landscape, the clouds of steam rising from a train. Degas and his Impressionist colleagues often incorporated trains, stations, and railroad bridges into their landscape paintings, considering all of these as indicators of modern life. The distant train was transportation that allowed the standing crowd to reach the day’s festivities, in contrast to the more affluent spectators, possibly horse owners, in the foreground. Thus, Degas’ painting records different social classes as well as most of the transportation modes available to Parisians at the time: feet, horseback, horse-drawn carriage, and railway.

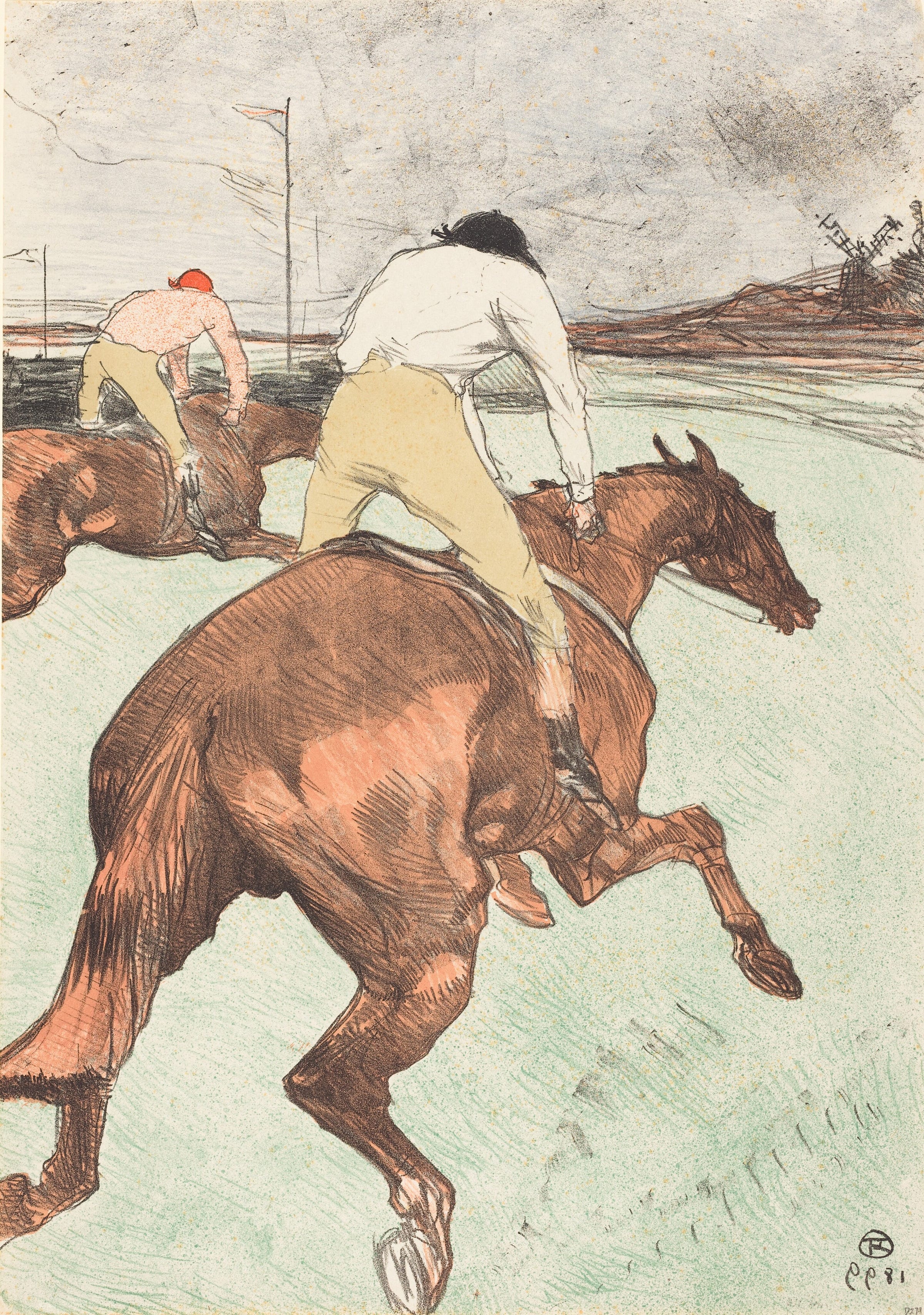

Just a short time after Degas’ painting, Post-Impressionist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (French, 1863 –1901) places the viewer right in the thick of a race in The Jockey, a color lithograph. This print-making technique had been developed about a century before and was used for printing both text and images. Of the printing methods available at the time, lithography was easiest for the artist to execute. The image was drawn on a smooth stone with a waxy or oily crayon. Though many lithographs don’t look like drawings, this is one effect that can be achieved, as the artist has done here. For a multicolored image like this, separate stones were used for each color. The drawn-on stone was treated with a weak acid solution to cut into the open areas of the stone making it able to absorb water. To print, the stone was moistened and then an oily ink would be applied. Because oil and water don’t mix, the ink would adhere to the drawn sections but not to the damp open areas of the stone. The printing process was usually overseen by a professional printer, though many modern artists have preferred to oversee the process, either closely or completely. Lithographs played an important role in Toulouse-Lautrec’s career; he created at least 363 posters and prints using the medium. His posters for the Moulin Rouge cabaret provided him with income independent of his family, although they continued to support him financially throughout his life. Prints like The Jockey would have provided additional funding and broadened his audience. The artist’s mastery of silhouette and outline are on display in this composition though the color palette is more restrained than in his cabaret posters. Toulouse-Lautrec effectively created the sense that he, and therefore the viewer, is atop another horse in the race following the two in the print.

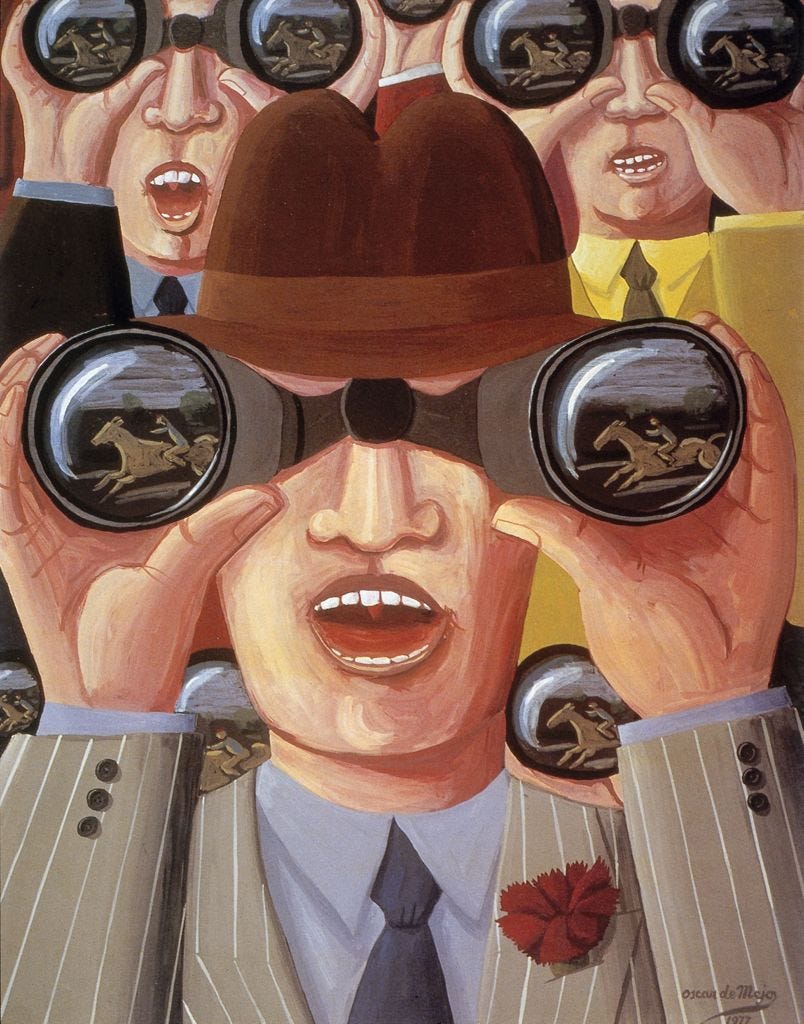

Another artist gives us a different perspective on a horse race in Kentucky Derby II. Oscar De Mejo (Italian-American, 1911-1992) had a varied career; he had degrees in both law and political science and after World War II, worked as a jazz composer until returning to painting, his first love. After the war, the artist married Italian actress Alida Valli and the pair moved to the United States. When he began painting in earnest, De Mejo frequently depicted scenes from American history as well as from American life during his own time. Sports themes like tennis, basketball, and The Kentucky Derby also drew his attention, especially in the 1970s. The artist’s style is usually described as naïve, but it is deliberately so. The artist was familiar with the history of art and like the French painter Henri Rousseau (1844-1910), De Mejo utilizes his somewhat child-like style to convey a sense that the scene takes place in a spiritual, magical, or historical world. His works are colorful, often include repetitive elements (as is the case here), and contain both humorous and surreal elements. Where Toulouse-Lautrec took us in to the rush of competition, De Mejo takes us into the stands, among avid, cheering fans glued to their binoculars which reflect a passing horse and jockey. The spectators’ faces are individualized as is the clothing worn by the men, but the binocular shapes exhibit De Mejo’s characteristic repetition. At first glance the scenes reflected by the binoculars’ lenses appear almost identical but a closer look reveals each is different. Then we realize that additional lenses are peeking over the shoulders of the man in the front and to his side, though there seems to be no room for people behind him.

Zooming out from the track, we encounter a famous and disconcerting image, The Race Track by Albert Pinkham Ryder (American, 1847-1917). Also known as Death on a Pale Horse, this painting is the artist’s most famous. Ryder was inspired to paint it after a friend wagered and lost $500 on an 1888 horserace (well over $16,000 in today’s dollars). In the aftermath, the artist’s friend committed suicide. Ryder spent several years working on the painting and apparently was reluctant to sell it. The work is eerie in its mood with thick, textured paint in dark tones. In the painting, a scythe-bearing skeletal figure rides clockwise around a racecourse. (Counter-clockwise racing was not standardized in the United States until the 1920s.) Study of the painting shows that the horse was originally represented naturalistically with its feet gathered under it, but Ryder changed it to show the feet in the old-fashioned flying position with all four legs outstretched. Across the bottom of the painting is a snake, also depicted in an old-fashioned bendy silhouette. Traditionally a symbol of temptation and evil, the snake combines with a dead tree, broken fence, and the figure of Death to create a mystical, eerie image of danger. Such symbolic imagery is typical of Ryder’s mature works and contrasts with both the realistic approaches of Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec and the stylized, abstract styles of Marc and Duchamp-Villon.

Now that the race is over, the horse relaxes in his pasture. Contemporary sculptor Deborah Butterfield (American, b. 1949) specializes in depictions of horses made from found objects in a variety of materials including metal and wood. Each of Butterfield’s horses has a distinctive personality. At first, she saw the works as metaphorical self-portraits but in recent decades she has made an effort to depict diverse equine personalities. She trains and rides horses on her Montana ranch so she has plenty of opportunities to experience those personalities. In some of the artist’s works, the found object construction makes up the final work but in others, especially in the last 20 years, the artist takes pieces of found wood, constructs the horse’s shape, carefully records the position and appearance of each piece of wood, and then has them all cast in bronze. Once the casting is complete, the artist patinates (or treats the surfaces of) the bronze sticks and branches so that they look like the original found wood. The illusionism of Butterfield’s patinas is impressive. One can stand very close to the finished work and still feel uncertain about whether one is looking at wood or bronze. The wood from which Bow Tie’s pieces were cast appears to have suffered from fire, with many dark surfaces covered with vertical and horizontal cracks. These dark areas contrast with the red orange tones of the rest of the wood, which emphasizes the horse’s shoulder, hip and legs. Like all of Butterfield’s horses, the posture and head turn, as well as the proportions of this horse, communicate its individuality.

Our day at the races has come to an end. Horses have fascinated artists in every culture and period that has known them and art is filled with every human and equine emotion. Whether you participate in The Kentucky Derby hoopla or not, enjoy your week. I’ll be back next Saturday with another post.

A thoroughly enjoyable post, once again—what an amazing variety of art on the theme of a day at the races you’ve chosen here. Only recently did I learn about the depictions of the galloping horse pre and post Muybridge—at the Manet/Degas exhibit when it came to NYC. I can only imagine how hard it may have been for viewers to adjust to the new reality he disclosed. The Manet/Degas exhibit had several horserace paintings, probably all well known to you, but I’ll offer three of them here as a small contribution to your wonderful post.

Manet’s “The Races at Longchamp” (1866): https://www.artic.edu/artworks/81533/the-races-at-longchamp

Degas’s “The False Start (ca. 1869–72): https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/26352

Manet’s “The Races in the Bois de Boulogne” (1872) https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/851694