Inspired in part by the exhibition “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (through July 28, 2024), I’m looking at the art and philosophy of the Harlem Renaissance in this edition. An intellectual and cultural flowering among black Americans, this movement was based in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City and began around 1917. The Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression affected the Harlem community as it did the rest of the country, but the creative community that had arisen there continued to produce and to attract young blacks through the 1930s, the 1940s and beyond.

Several developments within the United States encouraged the development of the Harlem Renaissance at the beginning of the 20th century. Increasing industrialization in northern cities combined with the lack of economic opportunity for blacks in the South led to the Great Migration, in which tens of thousands of people moved to northern cities for jobs. New York was not the only destination, of course, and other northern cities including Philadelphia, Washington, Chicago, and Detroit saw the development of black creative enclaves. Ambitious and like-minded people gathered in urban black communities, encouraging one another and building on their shared values. The first decades of the 20th century also saw the beginnings of mass culture, with the development of recorded music, the early stages of moving pictures, and widely available and affordable printed images and books.

Harlem had become a black community around 1900 and grew during World War I. Throughout the 1910s, racist violence, especially lynching, threatened black communities all over the United States. At the end of World War I, servicemen returning to the country further increased racial tensions. The summer of 1919 came to be known as Red Summer because of frequent outbreaks of white supremacist violence and racial riots. For black communities like Harlem, these terrible events drew the community together in the face of adversity. The cultural leaders of the Harlem Renaissance were active in responding to the outrages with peaceful protest marches, publications, and art.

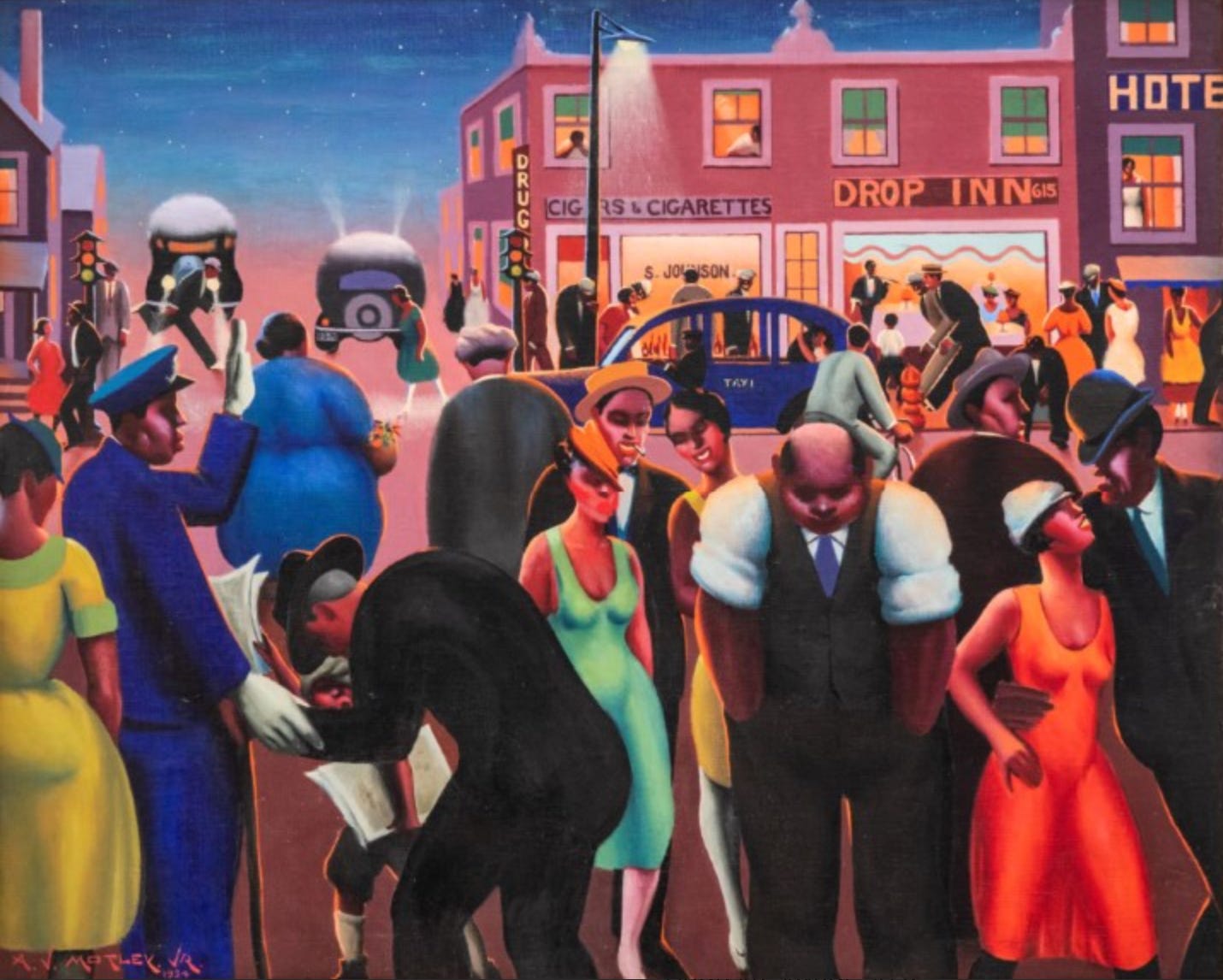

One of the most prominent painters of the Harlem Renaissance was Archibald Motley, Jr. (American, 1891-1981), in spite of the fact that he never lived in Harlem. The artist spent most of his life in Chicago, and graduated from the School of the Art Institute in 1918. At the time, the School was extremely conservative and Motley kept his colorful and energetic paintings secret for some years. Black Belt depicts a street scene in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood using the artist’s characteristic stylized approach. In this work, he blended memory and reality to display a variety of people and activities as twilight descends on the city. The police officer is based on a friend of the artist’s father; other figures demonstrate the mix of working folk and fashionable nightlife that occupy a city street as day turns to night. Scholars have recognized a connection between Motley’s scenes of nightlife and those created by French Post-Impressionist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec ( French, 1864-1901) while recognizing the artist’s importance as a representative of the ideals of the Harlem Renaissance.

What we now call the Harlem Renaissance was known at the time as The New Negro Movement, after the title of Alain Locke’s (American, 1885-1954) anthology of black writers, including Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, among others. Locke, whose portrait is on the left above, is considered the “Dean of the Harlem Renaissance” and was a leader in promoting the importance of black literature and art. Locke defined race as a social and cultural construct beyond heredity. His philosophy stressed self-confidence and political awareness and he valued the power of art and literature to evoke The New Negro for society at large.

The second portrait of the pair above depicts W. E. B. Du Bois (American, 1868-1963), one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and editor of the organization’s publication The Crisis from its first issue in 1910 until 1934. Du Bois, mentioned by Martin Luther King along with Locke as one of humanity’s great philosophers, also promoted black artistic creativity and the term Renaissance for the movement may lie in his use of the term to describe the development of black artistic expression in this period after what he perceived as a long hiatus of black creativity. For Du Bois, though, black artists had a moral responsibility to use their art as propaganda for black causes. Du Bois was also concerned that white consumers of black culture, especially those who flocked to Harlem’s music venues, were acting on a kind of voyeuristic urge, rather than true appreciation of black art. This concern had validity, as many white consumers were seeking an exotic experience and rejected those performers and artists who failed to provide that.

These two portraits were created by German-American artist Winold Reiss (1886-1953), who had settled in New York and was responsible for illustrations in the first edition of Locke’s The New Negro. Reiss’ distinctive approach to portraiture is apparent in these two examples, in which the faces are depicted with extreme naturalism while the rest of the figures are conveyed only by shadowed contour lines.

Portraiture and self-portraiture were important components of Harlem Renaissance artistic expression because these images of black creativity and dignity created images of “The New Negro.” It was believed that such images would communicate the shared humanity of blacks, a basis of demands for social and political equality. The beautiful watercolor Self-Portrait by Samuel Joseph Brown, Jr. (American, 1907-1994) conveys the artist’s dignity and humanity, as well as his skilled handing of his medium. The contrast between the mostly blue-toned self at right with the brown-toned reflection, as well as the different facial expressions suggests this painting might also depict the concept of double consciousness. As described by W. E. B. Du Bois in his sociological and autobiographical writings, double consciousness is a dual perception of self, caused by living as an oppressed minority in a society that contemptuously watches and judges.

Painted in 1937 (and repainted after 1940) by Palmer Hayden (American, 1890-1973), The Janitor Who Paints must be viewed as a kind of self-portrait too. Hayden had bounced from job to job while trying to acquire training as an artist, settling eventually for janitorial work. Through this job, he met an artist who encouraged him, which in turn led Palmer to study at Cooper Union and when he learned of a competition in 1926, he produced a work for which he won a prize and the gold medal. The New York Times reported his success with the headline "Negro Worker Wins Harmon Art Prizes: Gold Medal and $400 Awarded to Man who Washes Windows to Have Time to Paint." Ten years or so later, Hayden records the scene of himself painting in a closet-like space, surrounded by cleaning tools and a trash can. Though the artist was quite successful in the US and Europe by the time he created this painting, there can be little doubt that he was protesting that newspaper coverage when he created this painting. His style was often criticized by both black and white critics for repeating racist caricatures by using thick lips and cartoonish faces and gestures. These are less prominent in this painting but Hayden has remained a somewhat problematic figure among black artists as a result.

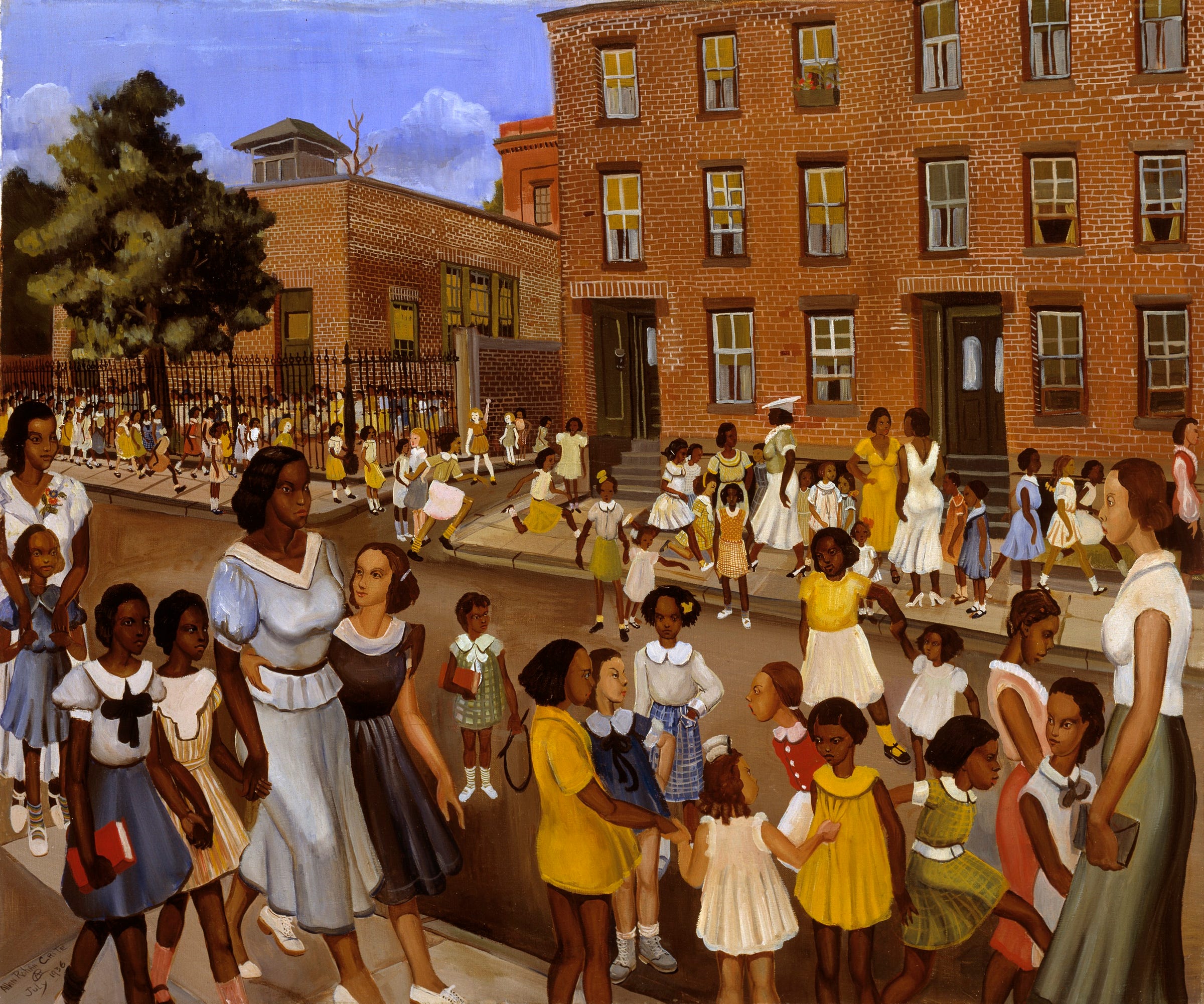

Another favorite theme of Harlem Renaissance artists was everyday life in the black community. Allan Crite (American, 1910-2007) was based in Boston and wanted to depict black life as an ordinary component of American society. School’s Out shows elementary school girls mingling with siblings and mothers in the street outside their school. The lively children contrast with their more serious elders; close observation reveals the kinds of interactions most of us remember from our own childhoods. Children race one another, wait for their adults with varying degrees of patience, and in the lower right, make faces or stare at one another with hostility.

I've only done one piece of work in my whole life and I am still at it. I wanted to paint people of color as normal humans. I tell the story of man through the black figure. – Allan Crite

Crite’s style is very naturalistic; it contains little stylization or Modernist abstraction. The artist has admitted that this work may be a romanticized view but it fits his artistic philosophy and desire to express universality. The warm red brick buildings convey stability and permanence while making a backdrop for the many white and yellow costumes. The bright blue of the sky is echoed across the foreground in a sprinkling of blue garments, tying the composition into a harmonious whole.

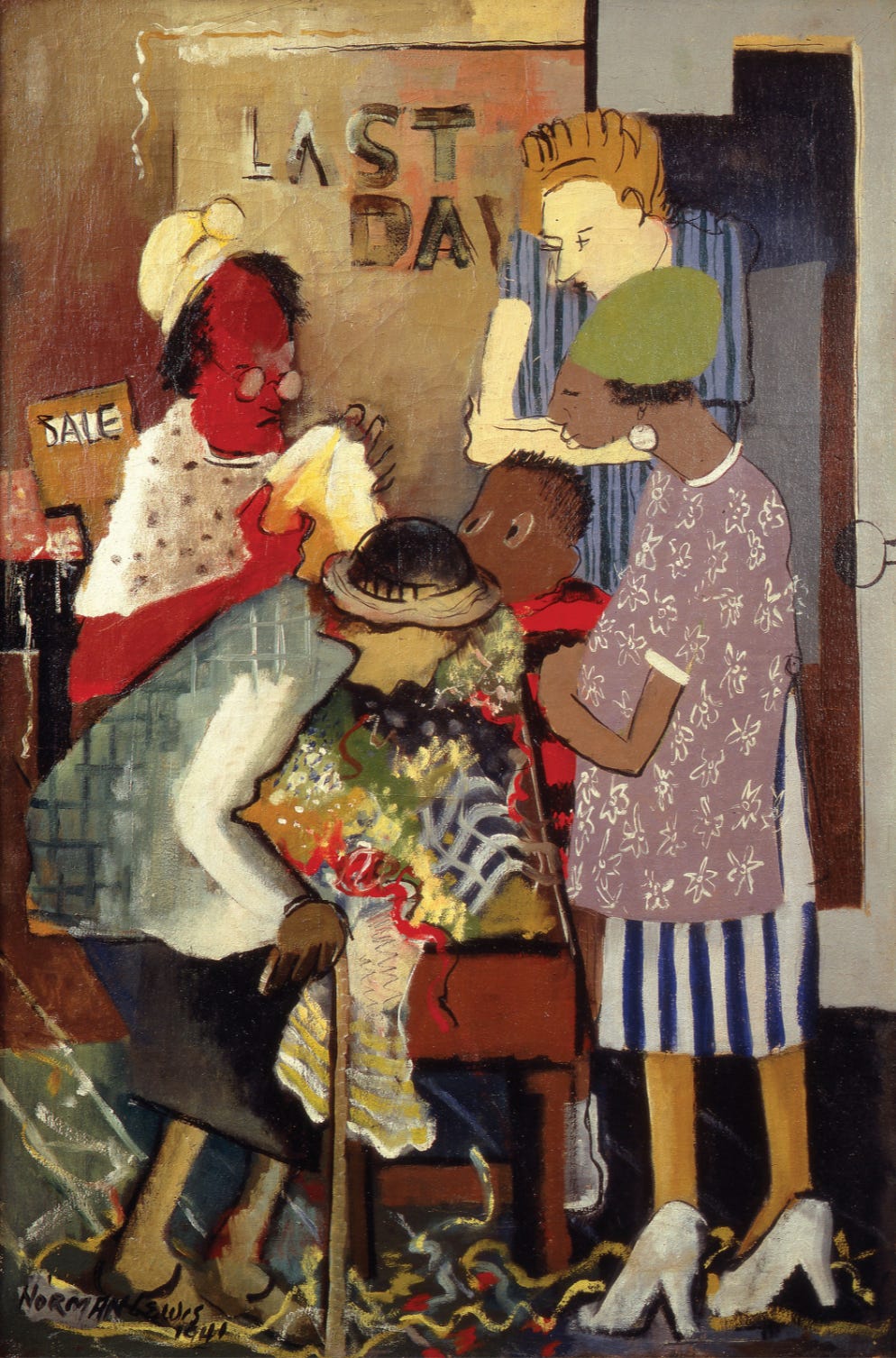

A more abstract and stylized approach is seen in Meeting Place by Norman Lewis (American, 1909-1979). The artist had studied with fellow Harlem Renaissance artist Augusta Savage (see below); Lewis joined Savage and others in Harlem, including author Ralph Ellison (American, 1913-1994) and painter Jacob Lawrence (below), to discuss the role of art and artists in society, and especially in black society. In this painting, from early in the artist’s career, slightly cartoonish figures pore over sale goods, with each figure distinguished by differently patterned clothing. In this approach, Lewis was adhering to a Social Realist style, popular in both black and white circles in the 1930s and 1940s. Later in his life, the artist told an interviewer that at the time he had believed in the power of art to change the way blacks were treated in the United States. After World War II, Lewis became disillusioned with that view and instead believed that the individual artist should focus on exploring his personal aesthetic development. Lewis also realized that his political and social activism could continue separately from his artistic work. In his later career, the artist was associated with Abstract Expressionism. (Learn more about Norman Lewis in Viewing Room 7 and about Abstract Expressionism in Chance Encounters 23.)

Photography had become an important resource for spreading imagery of all kinds by the early 20th century. In Harlem, the pre-eminent photography studio belonged to James Van Der Zee (American, 1886-1983). The studio served as a social and cultural hub for the community and the photographer captured portraits of the many middle class and well-to-do blacks in Harlem. The Metropolitan Museum owns the Van Der Zee Archive and many of his photographs are included in the museum’s current exhibition. One of those is Tea Time at Madam C. J. Walker’s Beauty Salon which shows a gathering in the reception area of the famous beauty salon belonging to Madam C. J. Walker (American, 1867-1919). Walker is in the Guinness Book of World Records as the first American female millionaire; she had made her fortune marketing her own cosmetic and hair care preparations for black women. Like Van Der Zee’s studio, Walker’s salon was a social hub in Harlem. The women gathered in the photograph are fashionably dressed and well-coiffed, excellent advertisements for their hostess’ business.

Painter Jacob Lawrence (American, 1917-2000) is one of the best known American modernists, known for his cycles of narrative paintings featuring important events and people in black history. Lawrence was supported by Augusta Savage and other artists in the Harlem community, encouraging him from a very early age. The artist was only 25 when he painted this work. From the beginning, Lawrence’s style was marked by brightly colored forms silhouetted against a flat backdrop with sketchy landscape elements. In this painting, a photographer captures a well-dressed family, to which the artist directs our attention with an explosive bright flash projecting from the camera. Around this central action, the life of the city street goes on: someone descends a manhole as a large truck passes along with a horse-drawn cart carrying household goods and pedestrians. Like many other Harlem Renaissance painters, Lawrence records his community, depicting the energy and vibrant life which surrounded him.

As mentioned above, Augusta Savage (American, 1892-1962) was an important teacher of artists in Harlem as well as an accomplished and honored sculptor in her own right. The daughter of a minister who viewed her sculpting as creating “graven images,” Savage persevered through that opposition and through personal and financial challenges to relocate from Florida to New York City, attend Cooper Union, and complete a four year degree in three years. In spite of growing success, Savage was denied the opportunity to study in France when the American selection committee discovered that the artist was black. Savage was 37 years old before she was able to travel to France. She spent two years traveling, studying and working in Europe, even receiving an award from the Paris Salon. When she returned to the United States, Savage opened her teaching studio with a grant from the Carnegie Foundation and in spite of the Depression. She welcomed any student who wanted to learn and throughout her career worked toward equal opportunity for blacks in the arts.

In the preparations for the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City, Savage was one of four women and two blacks to be offered commissions for art to be displayed at the fair. The sculptor’s theme was the contributions of black people to music and the result was a 16-foot tall painted plaster sculpture called Lift Every Voice and Sing. The sounding board of the harp shape took the form of an arm and hand supporting graduated singing figures; at the front was a seated boy holding sheet music inscribed with the title song, which had been written by Harlem Renaissance composers and brothers James Weldon and John Rosamond Johnson. The sculpture was one of the most popular works of art at the Fair and one of the most reproduced. Unfortunately, Savage couldn’t afford to have the sculpture cast in bronze and the plaster was destroyed at the end of the fair. The object reproduced above is one of several smaller bronze versions which were created; this one is fittingly in the collection of the University of North Florida located in Jacksonville, the birthplace of Augusta Savage, as well as of the Johnson brothers.

I close this edition with a work by one of the most important artists of the Harlem Renaissance, Aaron Douglas (American, 1899-1979). Raised in Kansas, Douglas attended college at the Universities of Minnesota and Nebraska, graduating from the latter in 1922. Intending to continue his art education in Paris, as so many American artists did, Douglas traveled to Harlem where he was persuaded to remain by the developing importance of the Harlem Renaissance; he was inspired in part by the writings of Alain Locke. The young artist studied with Winold Reiss (above) who encouraged him to use his art to create a sense of unity within the black community. Reiss also recommended Douglas to Locke as an illustrator for the second edition of The New Negro. Douglas created illustrations for many issues of W.E. B. Du Bois’ periodical The Crisis as well as for Vanity Fair and other publications. The style he developed incorporated the influences of European Modernism, including Cubism and African art, including the art of ancient Egypt. In addition to his illustration work, Douglas applied his distinctive style in mural projects from New York to Texas. The example included here is the final panel of a mural series which the artist created for the New York Public Library. Entitled Aspects of Negro Life, the murals were originally created for the 135th Street Branch which is now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Commissioned by the Works Progress Administration, a New Deal project which produced public amenities, the murals showed life in Africa in the first panel, the progress of blacks from slavery through Emancipation and on to Reconstruction in the second and widest panel and finally in this panel the difficult present and hope for the future. Three silhouetted figures appear across the foreground. At left is a seated figure under a skeletal yellow green hand; this figure symbolizes the enslaved past of American blacks. At the right, a figure struggles to climb a staircase-like gear while a green claw and yellow-green flames tug at him, symbolizing the economic challenges faced by blacks in the 1930s. The third figure stands atop the gear with a saxophone framed by mountainous skyscrapers; he is emblematic of the opportunities presented by the arts and music during the Harlem Renaissance. Visible through the narrow gap between the buildings is a figure with a raised arm as if urging the foreground figures forward on their journey. Like all of Douglas’ murals, this work combines abstraction, symbolism, and history with an aspirational message.

The Harlem Renaissance was the first movement to make black experience part of broader American cultural history. It redefined how the United States and the rest of the world perceived black people and was an inspiration for the later Civil Rights Movement. Though I’ve focused here on the visual arts, it was also a philosophical, literary, and musical movement. All of these aspects of the movement advocated for racial pride and for social and political integration. These progressive ideals were often challenged, not only by the broader white-dominated culture but also by conservative voices within the black community. For those who had achieved a measure of professional and economic success, the often radical voices of the younger generation were frightening and so they resisted supporting the insistence on creating a uniquely African American identity. Harlem Renaissance author Langston Hughes (American, 1901-1967) expressed the feeling of his generation when he wrote

We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. — from “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” (1926)

“The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” continues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City through July 28, 2024. (Many, but not all, of the works reproduced here are included in the exhibition.) LINK: https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/the-harlem-renaissance-and-transatlantic-modernism

We welcome your comments. Thank you for reading and subscribing.

A wonderful sample of art by black artists of life in black communities. This exhibit and your commentary is enlightening! Many thanks!

Really enjoyed your commentary and the art.