Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894) was an innovative Impressionist painter, exploring new themes and creating striking compositions in his works. He was also a supportive friend to his fellow Impressionists, using his inherited wealth to collect their works and support their movement. (See Chance Encounters 30 for more about Impressionism.) In connection with the 150th anniversary of the First Impressionist Exhibition and the 130th anniversary of the artist’s death, a major exhibition of Caillebotte’s work has just opened at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. Gustave Caillebotte: Painting Men focuses on the frequent appearance of male figures in the artist’s work, men of all social classes, in public and private, engaging in work and leisure activities. In this, Caillebotte’s work mirrors that of his fellow Impressionist Mary Cassatt (American, 1844-1926) whose work focused on the world of women and children. Both artists were following the movement’s philosophy of painting what you know, depicting the contemporary world as you experience it. In the second half of the 19th century, the worlds of women and men were largely separate. Women were often restricted to the home and family, associating with their children and with other women. In contrast, men lived public lives both at work and at leisure.

Caillebotte’s family was wealthy; his father had inherited a business which supplied textiles to the French military and built it into profitable concern. The family owned an estate outside Paris as well as property in the city. Though trained as an engineer and a lawyer, Caillebotte abandoned those careers in the early 1870s to become a painter. He studied with Léon Bonnat (French, 1833-1922), who prepared him to study at the École des Beaux Arts, the official French painting Academy, to which Caillebotte was accepted in 1873. As an artist Caillebotte had little interest in following the restrictive traditions of the Academy which stressed the use of idealized Neoclassical figures, precisely painted surfaces, and historical, religious, and mythological themes. Instead, the artist turned to the world around him, painting family members, views of Paris, and his well-known paintings of male laborers, such as Floor Scrapers (above). One of the first works to depict the urban working class, this painting was a sensation at the Second Impressionist Exhibition, in 1876, for its themes of strenuous male labor and comradery among the workers and for its point of view which stresses the position of the painter in the room, a fellow laborer though in a different field of work. Characteristic of Caillebotte’s approach, the space is carefully defined by mathematical linear perspective which the artist emphasizes with the scraped lines of the wooden floor. The balcony seen through the window is one which appears in many of Caillebotte’s paintings; this is the artist’s own Paris apartment in the process of renovation.

Physical exertion of another kind is the subject of Caillebotte’s many paintings of rowers. The artist himself was an avid participant in watersports, especially rowing and yachting. His family’s estate bordered the Yerres River, the setting of this painting. Like Floor Planers, Boaters Rowing on the Yerres, presents us with a vantage point that suggests the artist is in the boat with the oarsmen. By choosing viewpoints like these, the painter lures the viewer into the scene, because the painter’s vantage point becomes the viewer’s when the work is complete. The focus remains on the work of rowing, on the boat’s interior, and on the water surrounding the boat. The result is that we are boaters too, hearing the oars creak and watching the water slip past. Few artists of any period have had Caillebotte’s knack for inviting viewers to become part of their paintings.

Though the artist’s best known works are his figure paintings, Caillebotte also depicted still life, cityscapes, and landscape, in which he showed the typical Impressionist’s interest in the interaction of light and weather. In The Yerres, Effect of Rain, the artist captures the slowly widening ripples of raindrops as they begin to fall on the still water of the river. The raindrops distort the reflections of the trees on the far bank and of the light filtering down among the leaves. The visible brushwork in the leaves is also a typical device of Impressionist painters for capturing the momentary qualities they prized. More unique to Caillebotte is the very specific paint of view, from which the artist was able to apply his precise linear perspective to the beams bordering the near side of the river. Caillebotte’s combining of his academic technical training and Impressionist techniques and themes sets the artist apart from most of his Impressionist colleagues.

Scenes of the city of Paris were popular with some of the Impressionist painters, including Caillebotte. The artist painted several studies and two versions of the Europe Bridge, a large plaza bridging the railroad yards of the Gare Saint-Lazare. Structures like bridges, trains, and railroad yards were popular subjects among the Impressionists as symbols of the modern world. Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), for example, famously painted a dozen views of the trains at the Gare Saint-Lazare. In Caillebotte’s The Europe Bridge in the collection of the Musée du Petit Palais in Geneva, Switzerland, the bold metal trusses dominate the right side of the composition while the left side is bright and light with the road extending into the distant city. Between these two framing elements, we see four figures and a dog in the right foreground. The dog walks confidently away from the viewer, a device to draw our attention toward the human figures. To the right of the dog, a laborer in a workman’s smock leans on the railing and watches the trains. The artist contrasts this idler with the man in a green jacket who walks away from the viewer, pushing a loaded cart. Walking toward the dog is a flâneur, an affluent urban male who found detached entertainment in roaming the city and observing the actions of its inhabitants. He also provides a contrast, this time of class, with the two working men. Like the bridge, the flâneur was a symbol of modernity. The man turns and tilts his head toward the right, where a woman walks slightly behind him. It’s been suggested that she is a prostitute as a respectable woman wouldn’t have been walking alone in the disreputable neighborhood of the train station. Perhaps the flâneur is listening to her proposition. A scholar has suggested that the man instead is looking toward the idling laborer in search of a same-sex tryst. In creating this large, complex work, Caillebotte allows viewers to consider multiple layers of meaning, another aspect of modernity in art.

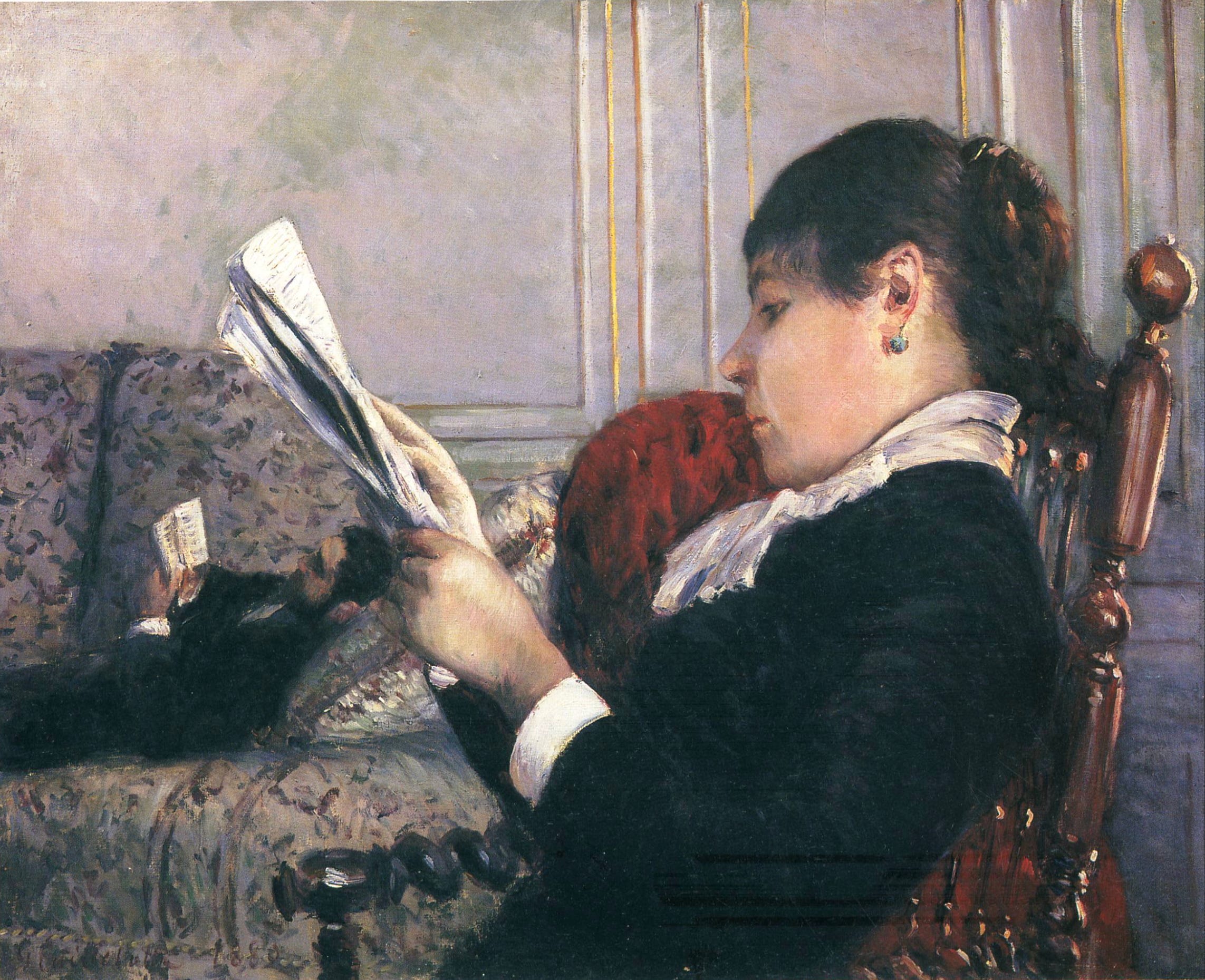

Though considerably smaller than the preceding painting, Interior, Woman Reading was far more controversial. Though it seems like an ordinary scene of everyday life to a contemporary viewer, in 1880 the painting was shocking because of the contrast between the depiction of the woman and the man. The woman is large and the man small. She sits upright; he almost disappears into the floral upholstery of the large couch. Finally, she reads a newspaper while he peruses a small book, perhaps a novel or poetry. Every one of these contrasts inverts the 19th century expectations of men and women. This work is one is several in which Caillebotte explores the positions of women, and especially, of men in 19th century Paris, as the current exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay highlights. The setting of this painting includes decorating details that appear in quite a few of the artist’s paintings, especially the floral sofa and the white and gold paneling. The latter is seen in Floor Planers, above.

Another of Caillebotte’s controversial works, painted around the same time as Interior, Woman Reading, is Nude on a Couch in the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art. This large painting is a statement of the artist’s commitment to unidealized realism, beyond even the depiction of nudes by Impressionist friends Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919) and Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917). This isn’t a classical goddess in a mythical space; Caillebotte has painted an obviously modern woman in an obviously modern setting. Reclining on the large floral couch seen in the preceding work is a slender young woman, her clothing lying on the cushion behind her head and her boots discarded on the floor beside her. The woman’s upflung arm shadows her face, but she appears to be asleep. Her open legs and the position of one hand near her breast, as well as the discarded clothing, hint at sexual activity. Apparently even Caillebotte feared he had gone too far with this painting as it was never exhibited or sold during his lifetime.

Another painting in which Caillebotte challenged European painting traditions is Man at his Bath. Painted in 1884, this painting was exhibited only once, at an 1888 exhibition in Brussels, held by the avant garde group Les XX (Les Vingts of The Twenty). Even in such a forward-thinking context, the painting was considered too shocking for public display. It was hung in a small, obscure room and attracted no attention from critics. The painting was owned by Caillebotte’s family and then by other private collections until 2011 when it was acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Like Interior, Woman Reading, this painting represents another inversion of 19th century gender expectations. Images of women, both idealized goddesses and more realistic modern women, bathing (usually titled “at their toilettes”), had been common in European painting since the 18th century. Caillebotte was likely inspired by Edgar Degas’ images of bathing women, known for their intimate but voyeuristic qualities. (See an example here.) To represent a man in a similarly intimate, even vulnerable, position was unheard of. The man reaches awkwardly to dry himself, having stepped from the tub (visible to the right), leaving wet footprints across the wooden floor. On a chair to his left, the man’s folded clothes await, with his boots on the floor beside the chair. As in Nude on a Couch, Caillebotte depicts an unidealized modern person. This painting continued Caillebotte’s longstanding project of recording the real lives of his society.

I close with the work that many consider Caillebotte’s most important painting, Paris Street; Rainy Day. One of the artist’s largest, this painting depicts a plaza in which a variety of Parisians scurry through the rain. The work may be familiar to some of our readers from its memorable role in the 1986 film Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Caillebotte presents this scene of urban life at the scale and with the seriousness which earlier artists had used to depict so-called history paintings, scenes of momentous themes from the past. For an Impressionist painting, this work was unusually well received by critics when it was exhibited at the Third Impressionist Exhibition in 1877. Critics responded positively to the carefully constructed space and the artist’s brushwork, which was more controlled than that employed by many of his colleagues. To more conservative critics of the time, the work was reminiscent of the style prized by the French Academy of Fine Arts, Once again, Caillebotte was challenging the traditions and expectations of his society, but once again Caillebotte was challenging the traditions and expectations of his era, even if his innovations weren’t apparent to some viewers.

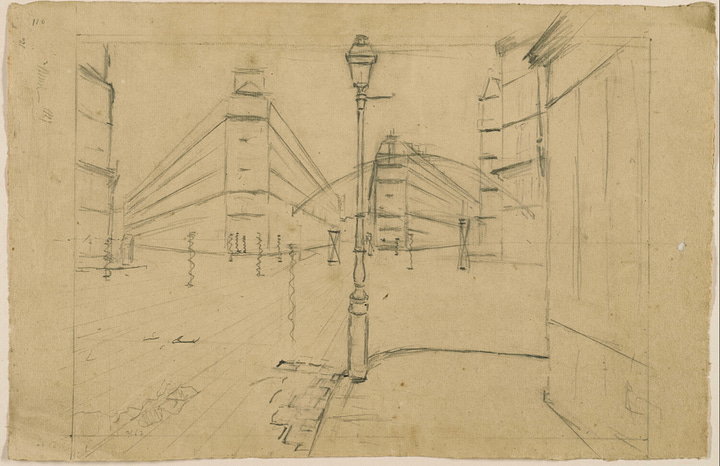

The three figures closest to the viewer are painted at nearly life-size and it feels as though they will step from the painting or that one could step into the city streets beside them. I’ve been fortunate to see this painting many times at the Art Institute of Chicago and it never fails to draw me in to explore the precisely rendered details and the activities of the pedestrians. The space Caillebotte depicted is the Place du Dublin (formerly the Carrefour de Moscou) and exists somewhat unchanged in Paris today. Five streets enter the plaza from different angles and the artist worked through many studies to execute the complex linear perspective system required to depict the space realistically.

These two preparatory sketches show how Caillebotte arranged a setting for his characters, even creating studies of the cobblestones on the street. His careful attention to detail remind us that the artist was a trained engineer, a job which required this kind of attention. Caillebotte also drew multiple figure studies, for all of the figures in the painting, including several focused on the couple walking toward the viewer. These fashionably dressed figures represent the wealthy bourgeoisie, noticed especially in the fur collar and hat of the woman and her earring, once thought to be a pearl but revealed as a sparkling diamond during a cleaning about 10 years ago. Other people included in the painting are from other social classes and include a female domestic servant (visible behind the large woman’s shoulder), a workman carrying a ladder (next to the large man’s umbrella shaft), street vendors, a pair of women walking away, men hurrying in pairs and individually, and other less identifiable figures disappearing along the streets. The Impressionist passion for conveying the momentary appears even in this carefully constructed composition, in details like the bent legs, and lifted feet of the pedestrians and especially in the thinly painted wagon wheel spokes that create an illusion of movement. Finally the shimmering light reflecting from umbrellas and the cobblestones shows the love of depicting the interaction of light and weather that Caillebotte shared with the other Impressionists.

In part because he didn’t need to sell his paintings to live, many of Caillebotte’s paintings remained in his family’s possession for many years during the artist’s life and after his death. His reputation suffered because of this and he was often thought a talented amateur who was more important for his support for his Impressionist friends than as a painter. There is no doubt that he was an essential patron to those friends whose financial situations were insecure. Caillebotte paid the rent for Claude Monet’s studio for a time and helped to fund the Impressionist group exhibitions. He purchased paintings from many of his colleagues, providing essential funds to Renoir and Camille Pissarro (French, 1830-1903) in addition to Monet. At his death at the age of 45, Caillebotte bequeathed his extensive collection of Impressionist paintings to the French state. Aware that the works were not yet valued by the French Academy or the State, he stipulated that the works must be exhibited at the Luxembourg Palace, dedicated to the display of living artists at the time, and later moved to the Louvre. The French state declined the bequest and Renoir, who was Caillebotte’s executor, was forced to negotiate to get any of the 68 paintings accepted by the government. In the end, 38 of the works were accepted for the Luxembourg and the rest of the collection remained with Caillebotte’s family. These were offered twice more to France in the early years of the 20th century, only to be refused again. In 1928, having finally seen the light, the government tried to claim the paintings but the widow of Caillebotte’s brother declined to follow through after the slights of the past.

In the second half of the 20th century, reassessments of Caillebotte’s own paintings began. The Art Institute of Chicago acquired Paris Street; Rainy Day in 1964, spurring American interest in the artist, and in the past 30 years several major exhibitions of the artist’s works have been staged, culminating in the exhibition now at the Musée d’Orsay. Gustave Caillebotte was the equal of his more famous Impressionist colleagues when it came to recording modern life and landscape and perhaps, superior to them in his compositional rigor and inventiveness.

I hope this quick look at a selection of his works will encourage you to learn more about the artist and perhaps inspire you to seek out the exhibition when it travels to Chicago and Los Angeles in the coming year, unless you’re fortunate enough to see it in Paris first.

Gustave Caillebotte: Painting Men continues at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France until January 19, 2025. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/whats-on/exhibitions/gustave-caillebotte-painting-men

The exhibition will appear at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, California, USA from February 25 to May 25, 2025 and at the Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois, USA from June 29 to October 5, 2025.

A wonderful overview! I always loved the Floor Scrapers painting, and had not realized he also painted the rainy Paris scene- quite an oversight. Happy to see more of his works here as well, thank you.

This made my heart glad. It’s a great essay. I’ll be seeing this in Paris next t week.