This week saw the centennial of the birth of Joan Mitchell (February 12) providing an excellent opportunity for me to explore the life and career of this accomplished American painter (1925-1992).

As she grew up in Chicago, Mitchell’s parents introduced her to art and literature from an early age and she was drawn to both painting and poetry. Her mother was a poet and edited a poetry journal and Mitchell herself considered a career in poetry. At The same time, the artist-to-be was attending classes at the Art Institute of Chicago. When Mitchell was 11, her physician father told her that in order to excel in a field, one has to focus exclusively on the chosen field. When it came time for college, Mitchell began at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, intending to be an English major. However, the young woman changed her mind and returned to Chicago to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, from which she earned BFA (47) and MFA (50) degrees. Now set on a career as a painter, Mitchell spent the remainder of her life devoted to expressing her life experiences through abstraction.

Linden Tree (Tilleul) is characteristic of Mitchell’s works of the late 1970s and is part of a series inspired by the title tree in different seasons. For this artist, landscape was a primary inspiration but she didn’t depict what she saw in a given moment.

I paint from remembered landscapes that I carry with me—and remembered feelings of them. . . . I could certainly never mirror nature. I would like more to paint what it leaves me with. – Joan Mitchell

In this example, the upper portion of the 8.5 foot tall canvas is covered with densely applied overlapping brushstrokes of green and blue, topped by a layer of orange strokes suggesting the vivid autumn color of the leafy tree. In contrast to these long, broad strokes, the lower part of the painting is marked by an array of irregular, dotted strokes in orange, yellow-green, and pale blue suggesting the texture of grass and fallen leaves shaded by the tree. Use of contrast, in this case of paint textures, is a characteristic of Mitchell’s art. Other contrasts that she applies in various works include dark vs. light, structured vs. chaotic areas, density vs. transparency, and harmonious vs. clashing colors.

Surviving works from Mitchell’s student years include still life and figure subjects and hint at her increasing interest in 20th century artistic developments. The still life above shows influences from Fauvism, in the colorful patches of the wall, and Expressionism, in distortions of shape and space. This untitled work is in the collection of the Joan Mitchell Foundation in New York. The Foundation was established by the artist’s will to protect her legacy and to support young artists, as she had done for much of her career. The Foundation awards grants and fellowships; recipients of whom you might have heard include Wangechi Mutu, Simone Leigh, Mark Bradford, and Amy Sherald. The Joan Michell Center in New Orleans is also supported by the foundation and offers artist residencies; these too have sponsored artists of growing fame, including Firelei Baez, Laylah Ali, and Alison Saar.

Mitchell’s works from the last years of the 1940s show a growing interest in the ideas of Cubism. The artist won a fellowship to live in France from 1948 to 1949 where she could have seen firsthand works by Picasso, Braque and other Cubists. By the time she created the 1950 painting Figure and the City, nearly everything is absorbed into a faceted design of lines and bars of color. Only the figure retains much sense of the original object, mainly through some organic contours and the yellow tones that stand out from the largely blue and lavender background. The artist later said that she knew at the time that this would be her last figural painting. From this point on, she shifted her subject to landscapes, urban and rural, always filtered through her memory and imagination and expressed through abstract shape and color.

Mitchell returned to New York City after her fellowship and began to participate in the life of a young avant garde artist in the city. She became friends with artists Philip Guston, Franz Kline, and Willem de Kooning, joining them in drinking and exchanging ideas at gathering places like the Cedar Tavern, where the Abstract Expressionists honed their philosophy from the 1940s on. (For more on this movement, see Chance Encounters 23.) Mitchell is one of the relatively small group of women to gain some success in the male-dominated group. She received her first solo show in New York in 1952. Though the artist shared the Abstract Expressionist belief that her work should be “authentic,” that is, a direct expression of her individuality and unique experiences, Mitchell disliked having any labels applied to her work. Nevertheless, she has long been considered one of the important artists of the Abstract Expressionist movement.

By the mid-1950s, the artist was spending more time in France, combining European ideas about abstraction with the practices she had developed in New York. (For more about European art of this period, see Chance Encounters 8.) Hemlock is characteristic of Mitchell’s work at this time, constructed of a mix of slashes and blotches of deep color surrounded by an airy environment of paler color. As was her usual practice, the artist named the painting after it was completed, this time in reference to Wallace Stevens’ 1916 poem Domination of Black. The poem speaks of the interaction of nature and memory; the last stanza says

Out of the window, I saw how the planets gathered Like the leaves themselves Turning in the wind. I saw how the night came, Came striding like the color of the heavy hemlocks I felt afraid. And I remembered the cry of the peacocks.

Like Mitchell, Stevens takes the inspiration of nature and expresses it subjectively as a reflection of both his external and internal landscapes.

The artist relocated permanently to France in 1959, living at first in Paris. She had met Canadian artist Jean-Paul Riopelle (1923-2002) there in 1955 and by the time Mitchell moved to Paris, the two had become romantically involved, a tempestuous relationship which continued until 1979. The success Mitchell had experienced in New York expanded internationally during the late 50s and 60s as her work was included in major shows in Italy, at the 29th Venice Biennale (1958), and in Japan, Germany, and Brazil.

Mitchell’s works of the first years of the 1960s were marked by her experiments with new methods of applying paint, which included flinging paint at the canvas, squeezing it directly on to the surface, and even spreading it with the her fingers. Lucky Seven contains some of the slashing strokes of Hemlock and other paintings of that earlier stage of Mitchell’s career, but it is dominated by large masses of color, smeared passages, and areas with flecks and dripped paint. The artist described this period’s works as “very violent and angry” and said that in 1964, she began to reject this approach deliberately and work in a brighter, more lyrical style.

In 1967, a bequest from her mother permitted Mitchell to purchase a two acre property in Vétheuil, on property once partially owned by Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926). The artist said she bought the property so she would no longer have to walk her dogs in the city. The Joan Mitchell Foundation has found over 1600 photographs of dogs and puppies among her painters, and expects to find more. (Most of the photos I take show my dogs and cat, too.) The new home also allowed the artist to immerse herself in nature and she emphasized variety and brightness in her color choices, as seen in Sunflower III, one of a series on the subject.

They look so wonderful when young and they are so very moving when they are dying... I like them alone or, of course, painted by Van Gogh. – Joan Mitchell

She had known Vincent van Gogh’s work since her childhood visits to the Art Institute of Chicago and in many of works from the late 60s and 70s, she seems inspired by his rich color, nature themes, and bold brushwork. The forms in Sunflower III convey the upright growth and heavy heads of mature sunflowers, but by depicting only masses of color and squiggly lines in a glowing atmosphere, the artist embraces the ability of abstraction to suggest multiple moods and meanings.

Another image inspired by Mitchell’s rural surroundings is Plowed Field. In this case, she renders a panoramic view across three canvases (triptych), over 17 feet wide in total. The crisper edges of the canvases act almost like property lines, and contrast with the uneven edges of the color masses. The artist had been creating multi-paneled canvases since the early 60s; the expanded size allowed her paintings to envelop the viewer almost as a person could be surrounded in nature.

The freedom in my work is quite controlled. I don’t close my eyes and hope for the best. – Joan Mitchell

The bold and varied marks with which Mitchell filled her canvases might lead viewers to imagine that these were created in frantic sessions of instinctive creation. The artist’s process, though, was quite deliberate. In many cases, she sketched her compositions in advance, often on the canvas before beginning to paint. This planning and structure is more apparent in some works than others; for example it is seen more in Hemlock and Plowed Field, and less in Lucky Seven and Sunflower III. As the artist matured, she grew to know her materials and techniques and could deploy them to desired effect almost instinctively, but she worked slowly, She described sitting with a composition for hours or days while deciding whether there was more to do.

The mid 1980s were a difficult time for Mitchell. Longtime friends were caught up in the AIDS crisis and were dying. The artist was diagnosed with advanced oral cancer, which was cured by radiation treatments that caused damage to her jawbone. Later she suffered from arthritis and underwent hip replacement surgery which unfortunately failed to alleviate her pain. Through it all, Mitchell continued to paint.

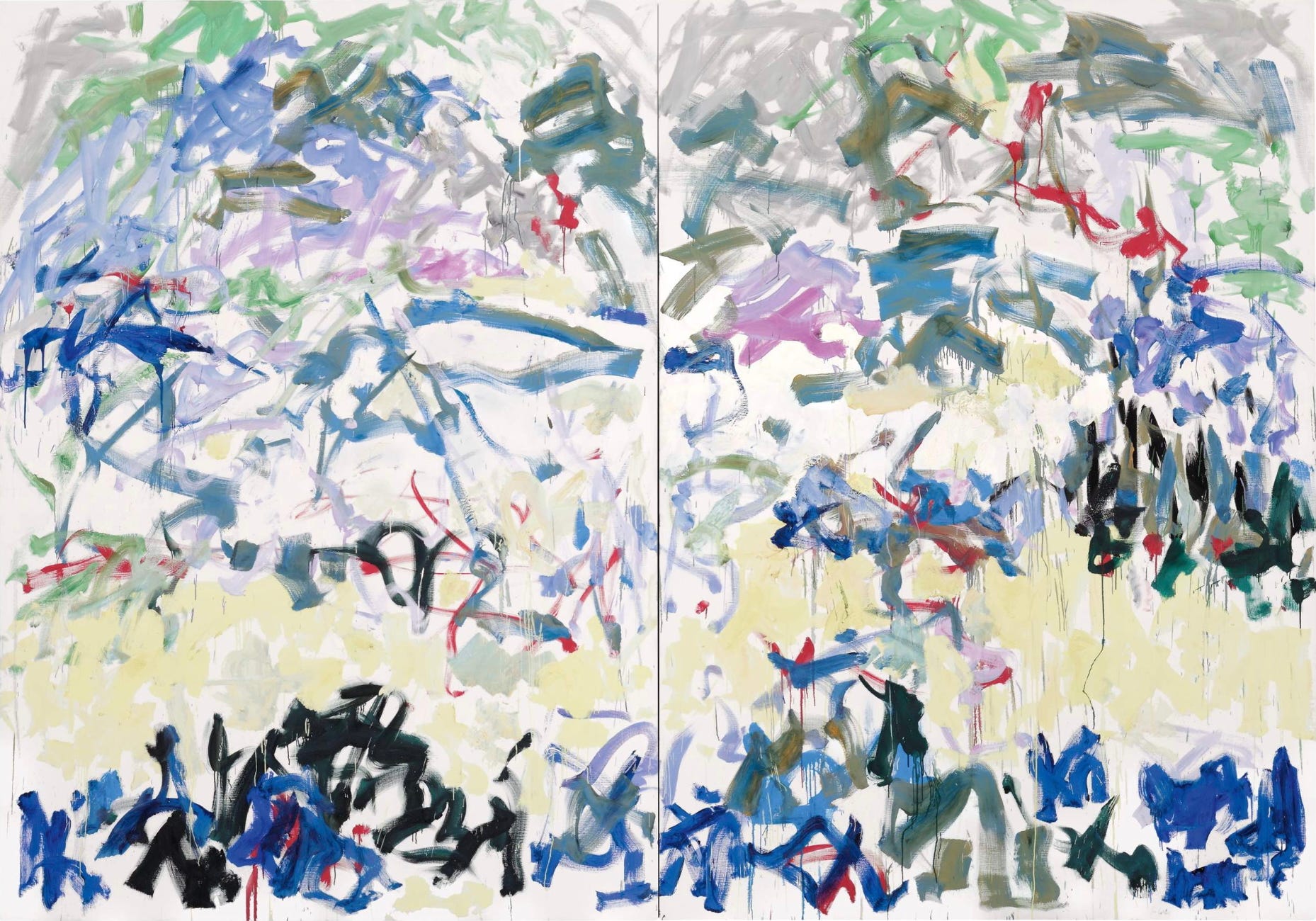

River is part of a series from this phase of the artist’s career. In spite of her difficulty mounting ladders and working on a large scale, this diptych (two-panel work) is over 13 feet wide. The colors are less intense than many of Mitchell’s earlier works but the influence of her famous predecessor in painting this landscape is apparent. Impressionist Claude Monet had lived at Vétheuil before moving to his more famous home at Giverny. Monet’s late waterlily paintings are often cited as the predecessors of Abstract Expressionism because of the large-scale canvases (some 20 feet wide or more) and the shifting of the angle of view down into the water. The late canvases were fields of color overlaid with blotches and swirls of color.

Mitchell’s River shares the palette of many of Monet’s late paintings, but her approach is more open and calligraphic than his. The pale yellow band suggests a river reflecting sunlight while streaks of deep blues and greens call to mind the thickets along a river bank. A host of paler colors across the top half of the composition can be read as mist dissipating in the morning sun and call to mind the artist’s words about the landscape of Vétheuil.

Yellow comes from here [Vétheuil]...It is rapeseed, sunflowers...one sees a lot of yellow in the country. Purple too...it is abundant in the morning. – Joan Mitchell

In early October 1992, Mitchell was visiting New York to see a retrosprctive of work by Henri Matisse (French, 1869-1954), another of her artistic inspirations, when she visited a doctor who diagnosed advanced lung cancer. The artist returned briefly to Vétheuil, before entering a hospital. The artist died on October 30.

Joan Mitchell undoubtedly excelled in her chosen field, through her intense focus on the inspiration of nature and determined pursuit of techniques of painting that would express her experience of all she had seen and felt. Her paintings create extraordinary bouquets, gardens, and fields of color in which the viewer can escape from the mundane world.

Music, poems, landscape and dogs make me want to paint…and painting was what allows me to survive. – Joan Mitchell

Exhibitions celebrating Joan Mitchell’s centennial:

“Honoring Joan Mitchell,” Museum of Contemporary Art, Jacksonville, Florida, USA, February 1-June 15, 2025. https://mocajacksonville.unf.edu/exhibitions/pop-up-space/honoring-joan-mitchell.html

“Collections in the Garden.” Musée des Impressionismes, Giverny, France. Including Monet, Mitchell, and other artists inspired by gardens. July 11 – November 2, 2025 https://www.mdig.fr/en/exhibitions/collections-in-the-garden-andrea-branzi-the-realm-of-the-living/

The Joan Mitchell Foundation website shares a list of museums in the United States and around the world where works by the artist can be seen this year. https://www.joanmitchellfoundation.org/joan-mitchell/where-to-see-mitchells-work-in-2025

Thank you for subscribing and reading. Please comment, like, and share. I’ll be back with more art soon.

Excellent article that has enhanced my appreciation for the Remarkable talent of Joan Mitchell

I wish I could get up close and personal with Hemlock. I knew nothing about Joan Mitchell. Thanks for this.