Chance Encounters, Edition 67

Félix Vallotton: “When He was Good, He was Stunning” **

Welcome back and thanks for joining me for a new year of art adventures. This edition is dedicated to the Swiss-French artist Félix Vallotton (1865-1925), a master printmaker and member of the Post-Impressionist art movement known as Les Nabis.

As a teen, Vallotton was accepted into an advanced drawing class where he was known for his realistic, closely observed work. Upon completion of this course, the young artist convinced his parents to allow him to study art in Paris. From that point, Vallotton devoted himself to becoming a painter. He studied at the Académie Julian where the young artist perfected his technical skill and made friends among his fellow students. Like other young artists of the time he visited the Louvre frequently to study the art of his predecessors; Vallotton admired Renaissance artists Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer, but his favorite was the Neoclassical painter J.A.D. Ingres (French, 1780-1867). Ingres is known for his precisely depicted portraits and porcelain-skinned nudes, and these were subjects for which Vallotton became known in his career. In 1883, the artist was accepted as a student in the prestigious École des Beaux-arts (Academy of Fine Arts), though he chose to remain with his friends at the Académie Julian.

Among those friends were Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, founders of Les Nabis (The Prophets), a group of young artists who believed that art was a mystical calling to convey the truths underlying appearances. In 1892, Vallotton was invited to join the group and for a while his works showed a strong influence from his Nabis colleagues. The Ball, above, is an excellent example of this phase of the artist’s career; unusual vantage points, in this case as if seen from a high window, were popular among Les Nabis. Unique to Vallotton are the patches of color with little detail and the strong contrast of light and shadow. The light is especially important here as it draws our attention to the child chasing a ball and to the tiny figures in blue and white. The massed shadows between the child and the adults emphasizes the separation between the figures, but perhaps also the psychological distance between youth and adulthood.

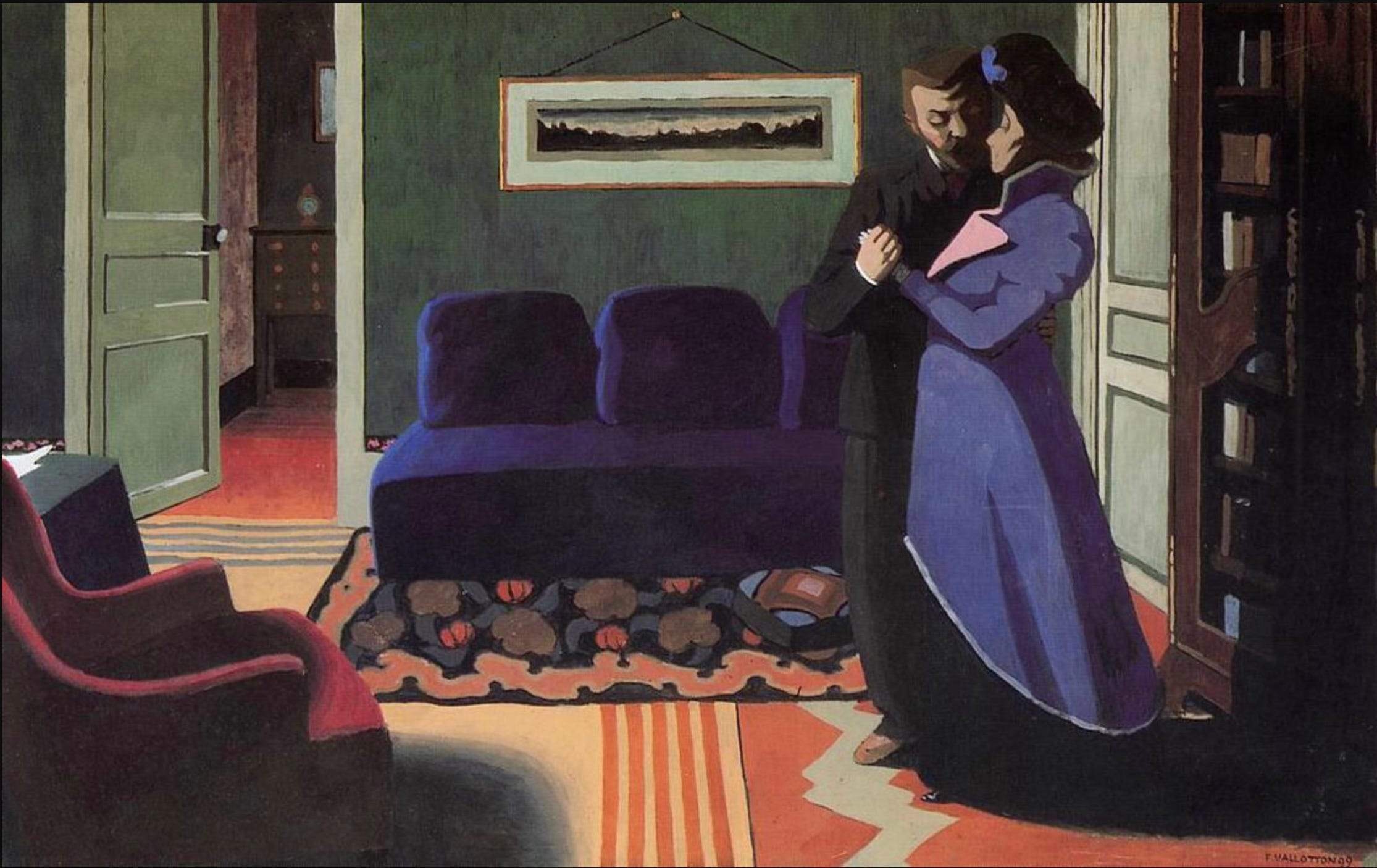

Painted the same year, The Visit has an intimate interior setting often used by Bonnard and Vuillard, but it lacks the painterly form and dense patterns those artists are known for. Instead, Vallotton’s painting has areas of deep shadow and intense color that create a mood of dramatic mystery. A man greets an elegantly dressed woman with an embrace. His dark clothing and shadow blend with the black border of her coat which in turn merges with her deep shadow at the right edge of the painting. This shadowy interaction suggests intrigue and illicit passion, which is reinforced by the brightly lit doorway to, a bedroom at the right. The fashionable apartment and dress identify the theme as the immorality of the Parisian upper class, a favorite target for criticism of Vallotton’s in his paintings, drawings, and prints.

[T]he figures don't just smile and cry, they speak … they express strongly, with the most moving eloquence, when it is Monsieur Vallotton who hears them speak, their humanity and the character of their humanity. – Octave Mirbeau, French critic (1848-1917)

As a young artist in Paris, Vallotton was hard-pressed to earn a living from his paintings. His family, which had provided some financial support, fell on hard times around the same time, so the artist worked several jobs to pay his bills. For 7 years, he contributed articles about the Parisian art world to a newspaper in his Swiss hometown of Lausanne; he worked as an art restorer for a Paris gallery, and most importantly he began to contribute sketch portraits, illustrations, and prints to periodicals, books, and theater programs. This work, along with occasional commissions for paintings, allowed Vallotton to be financially secure in the last decade of the 19th century.

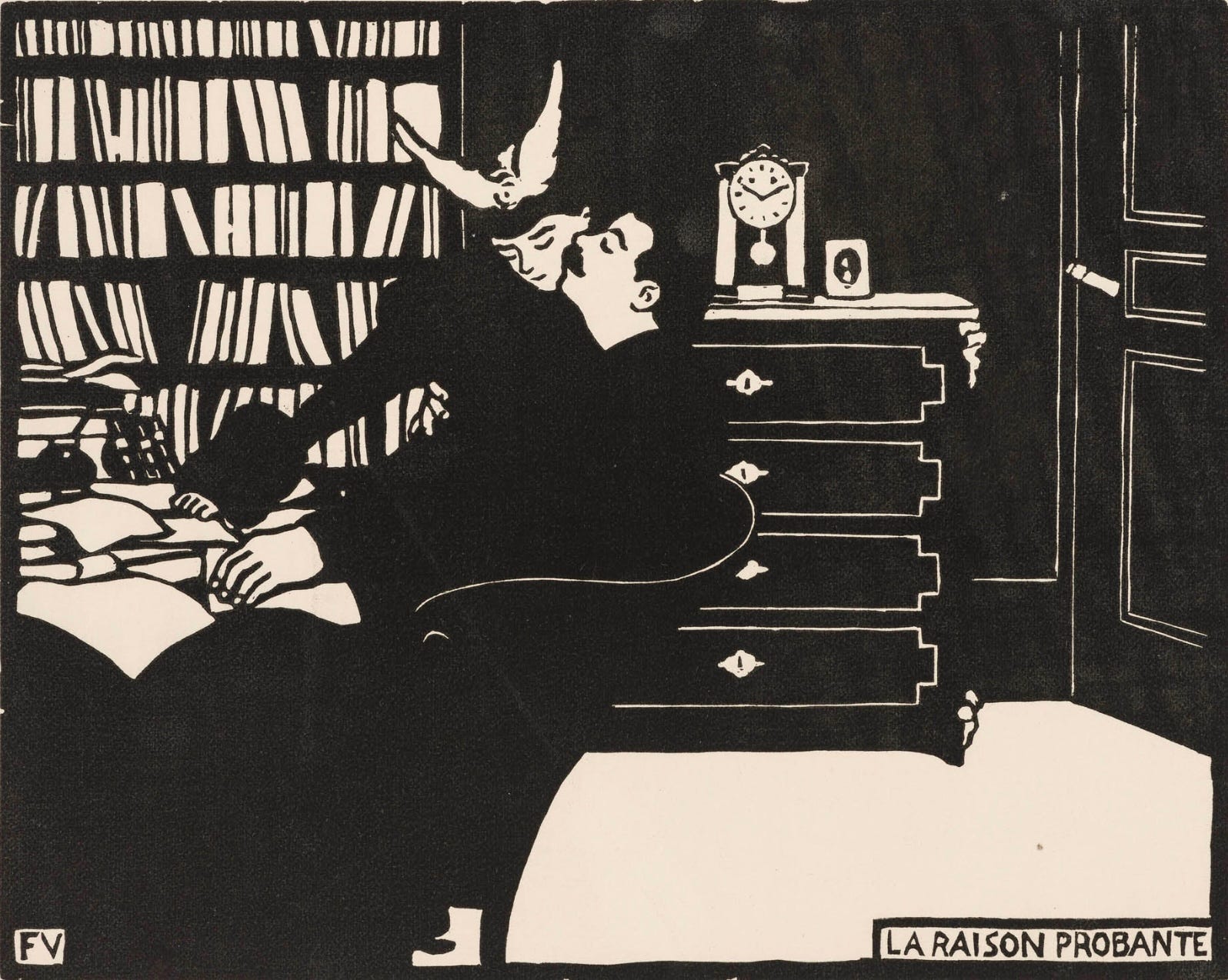

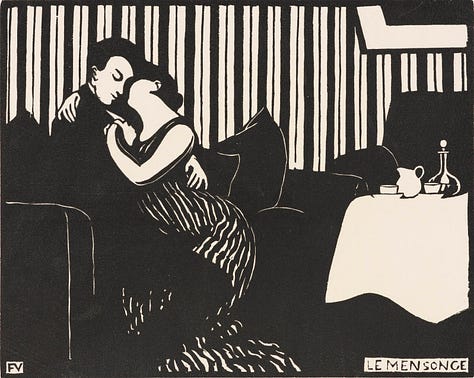

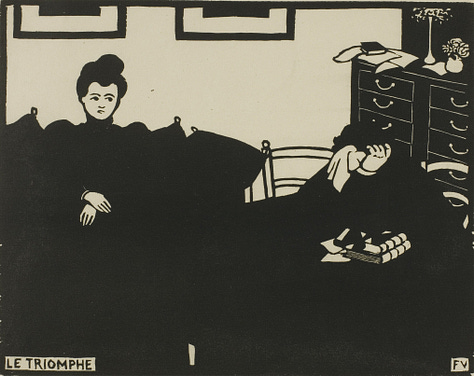

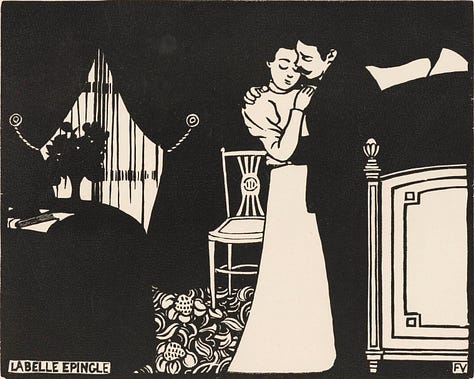

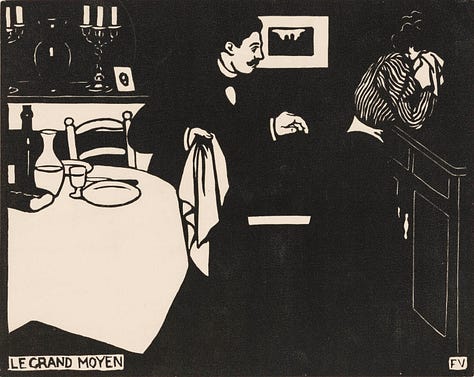

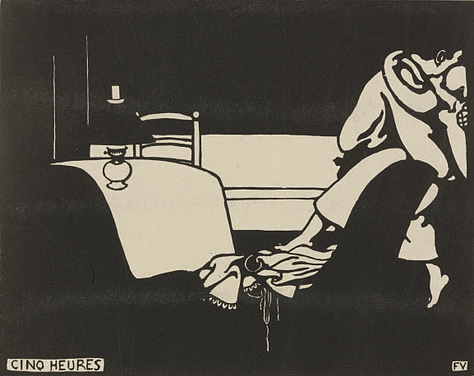

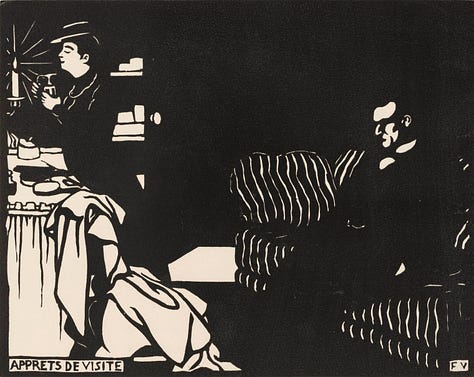

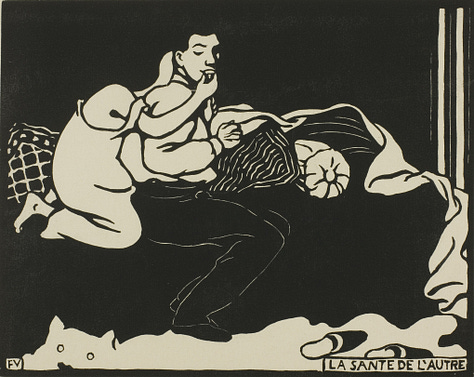

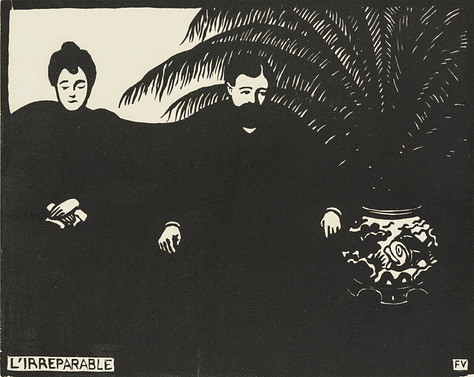

Vallotton’s prints were so popular that in 1898, La Revue Blanche published a portfolio of 10 prints called Intimacies (Intimités). The series shows men and women in dramatic scenes with titles suggesting the nature of the interaction. Faces and bodies emerge from large areas of flat black ink, often with an area of bold pattern to intensify the contrast. As in The Visit, the people in Vallotton’s Intimacies demonstrate a troubling reality underlying the carefully cultivated image of fashionable Parisians. The Cogent Reason above is the fourth print in the series and shows a woman bending to receive a kiss from a man seated at a document-covered desk. Her hat is decorated by a white bird in flight – perhaps hinting at a desire to escape? The other prints in the series are included in the gallery below; each showing a different emotionally-fraught relationship between a woman and a man.

The technique Vallotton used is woodcut or woodblock printing, a form of relief printing in which the image is cut into a wooden block. Ink is applied to the raised areas of the block and transferred to paper. It was the earliest form of printmaking to develop but fell out of favor during the Renaissance when the intaglio methods of engraving and etching were invented. Vallotton is credited with revitalizing the woodcut method in the late 19th century and his works inspired younger print artists, Edvard Munch, Aubrey Beardsley, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Vallotton’s process for developing a print composition was to begin with a detailed, naturalistic drawing and simplify it repeatedly until he achieved the bold designs for which he is famous.

An important drawing by Vallotton survives, depicting a café crowded with newspaper readers. Known as The Age of Newspaper, the drawing was designed for the left wing publication Le Cri de Paris and was one of a series of satirical images the artist created in response to the Dreyfus Affair, a political controversy in France that lasted from 1894 to 1906. Dreyfus, an army officer of Jewish descent, was wrongfully convicted of espionage. Exonerating evidence was suppressed, multiple trials took place, and disagreements over the case tore apart friendships and alliances. Vallotton, passionately pro-Dreyfus, grew apart from some of his Nabis colleagues at this time because of the issue. In the drawing, each reader has a different newspaper and Vallotton seems to suggest that all of these different news sources are dividing people from one another. The connection to this controversy is apparent from the headline nearest the bottom of the composition “J’Accu…” which refers to author Émile Zola’s famous public letter in response to the anti-semitism and cover-up in the case.

After marriage into a well-off family, Vallotton gradually gave up his print work in order to focus on his painting. We are fortunate to know the artist’s work history in detail because he kept a journal recording every work he made from 1885 on. At the artist’s death, it listed over 1700 paintings, about 200 prints, hundreds of drawings and even a few sculptures. Not only does this indicate the precision of Vallotton’s nature but also his determination to progress as an artist.

From 1907 on, Vallotton experienced increasing sales, though some critics complained about a detached dryness in his post-Nabis work. That detachment was present long before 1907, however, especially in his portraits and its source can be traced to his love of Ingres. Vallotton’s work lacks the idealization that Ingres applied to all of his figures however. This is especially apparent in The Purple Hat, in which a woman wearing a large feathered hat is shown lowering her chemise, though she still seems to be wearing her corset and skirt. Her facial expression is rather blank; she appears unaware that she is being observed. The result is an uncomfortable awkwardness that is only heightened by Vallotton’s color choices. The bright red violet hat is contrasted with the greenish yellow background. The artist was known for using complementary color pairs, especially red and green, in his nudes, but his choice of this unusual complementary pair sets this painting apart from his own body of work as well as from the tradition of using images of women to seduce the viewer. Works like this have led some recent scholars to see Vallotton’s work as a precursor to the rejection of romantic idealism characteristic of the 1920s movement Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity). (For more, see Chance Encounters 51 https://irequireart.substack.com/p/chance-encounters-edition-51.)

I dream of a painting free from any literal respect for nature. – Félix Vallotton

n his later landscapes, Vallotton avoided conventional compositions and techniques resulting in some of his most appealing and at times spectacular paintings. Sunset of 1910 is one of the latter. The palette of golds and oranges contrasted with an array of purples captures a dramatic view of the sun setting behind a ridge. The flare of orange in the lower third of the canvas may have been inspired by Vallotton’s practice of using photographs to capture potential subjects. Rather than working on site for these paintings, the artist combined sketches, photographs, his memory and imagination. The resulting work has a sense of heightened reality that is characteristic of some later artists such as René Magritte (see https://irequireart.substack.com/p/chance-encounters-episode-60) and Edward Hopper.

Vallotton had acquired French citizenship in 1900 and with the advent of World War One wished to demonstrate his patriotism by joining the French army. Unfortunately he was already 48 years old and was rejected when he tried to volunteer. Instead he returned to making prints, this time with patriotic and pro-military themes. In June of 1917, the artist was sent to the front with a delegation of artists so he could create more convincing views of the war’s effects. Many of the paintings that resulted from this trip were realistic but Verdun uses abstract form and color to create an emotional expression of Vallotton’s response to the battlefield. In some ways, this work looks back to some Nabis ideas but it also indicates that even though the artist was no longer active in the avant-garde, he was familiar with early 20th century developments in Expressionism, Cubism, and Futurism.

More than ever the object amuses me; the perfection of an egg; the moisture on a tomato; … these are the problems for me to resolve. – Félix Vallotton, 1919

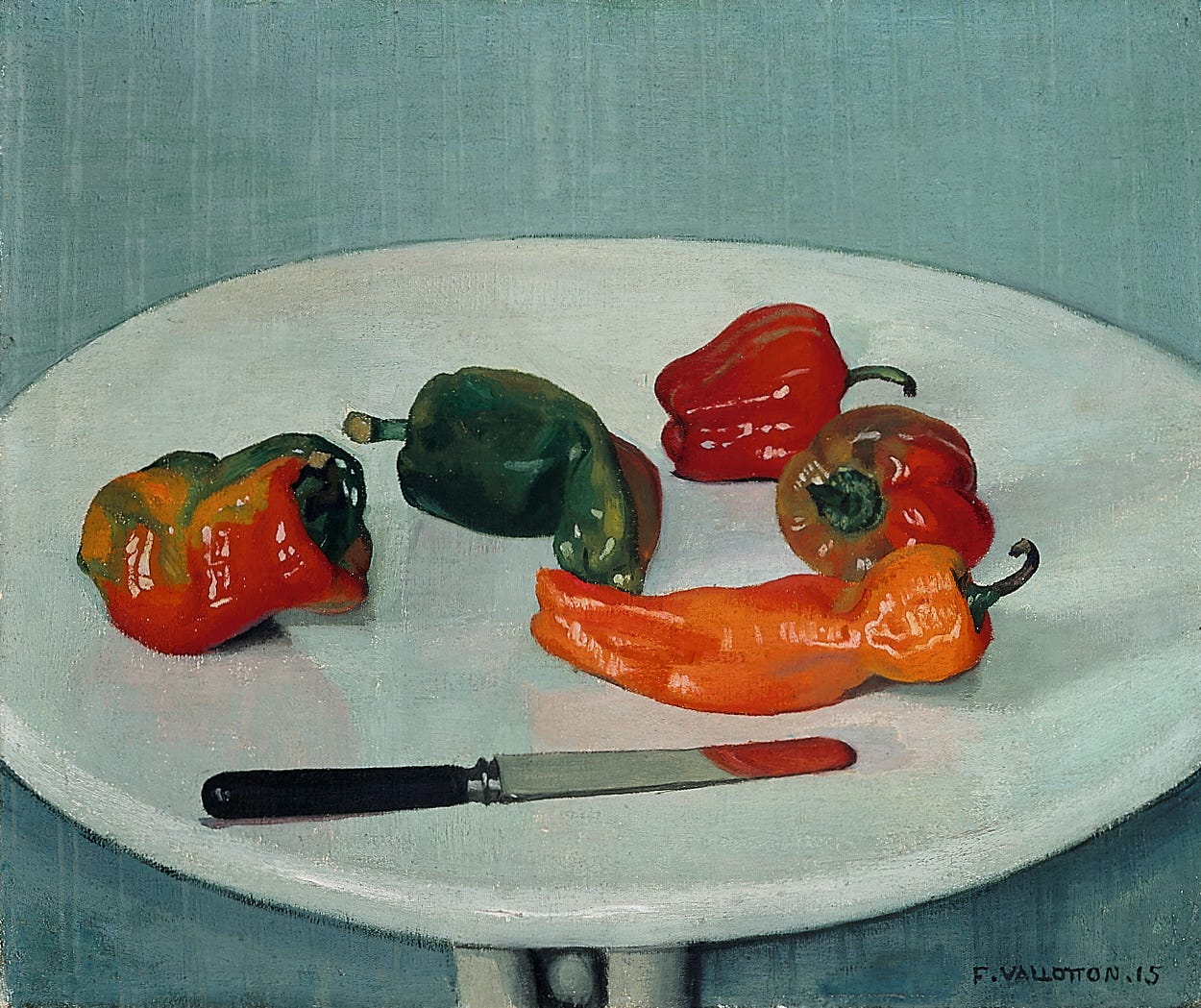

Still life subjects occupied much of Vallotton’s late career, many characterized by conventional compositions executed in vivid color. Red Peppers stood out to me as particularly contemporary in its conception, however. The white metal table reflects some of the blue background color but its shiny surface contrasts with the vertical striations in the blue paint suggestive of a wallpaper pattern. The peppers seem dropped at random on the table, their rich colors and irregular shapes at adds with the smooth white table. It is the knife that captures my attention though, black handle against white table, man-made straightness against the irregular peppers. Why is the tip of the knife red? If it is reflecting part of a pepper, why is only a small part of the flat blade red? It almost looks like the knife was dipped into red paint, breaking the illusion and reminding the viewer that a still life painting is an artificial construction of inanimate objects and as Vallotton’s fellow Nabis Maurice Denis said, “a picture … is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.” An artist hinting at the artificiality of his creation is something seen in 20th and 21st century Conceptual and Post-Modern art.

During the artist’s lifetime, Vallotton’s paintings were often met with confusion and even ridicule. He was seen as out of step with both traditionalist and avant-garde art yet he never wavered from the path he had embarked upon. Vallotton can be seen as partial evidence of the inaccuracy of the idea that Modern art evolved as one avant-garde movement following another. Instead a wide variety of styles were made possible by the rejection of tradition in the second half of the 19th century and Vallotton’s was both innovative and influential. In addition to the influences on printmakers and painters mentioned above, scholars have seen Vallotton’s influence in the work of filmmakers Fritz Lang and Alfred Hitchcock and more recently in the films of Wes Anderson.

Life is smoke. We struggle, we delude ourselves, we cling to ghosts that give way beneath the hand, and death is there. Happily, there is still painting. – Félix Vallotton

The 100th anniversary of the artist’s death was marked in 2025 with exhibitions across his homeland of Switzerland. This included the publication of an online catalogue raisonné of Vallotton’s illustration work (https://vallotton-illustrateur.ch/catalogue) as well as print volume of critical essays on this same body of work.

The last two exhibitions of this année Vallotton will close on February 15, 2026. These are Vallotton Forever. The Retrospective (https://www.mcba.ch/en/exhibitions/vallotton-forever/) and and Vallotton. The Ingenious Laboratory (https://www.mcba.ch/en/exhibitions/vallotton-the-ingenious-laboratory/ ) at Musée cantonal des beaux-arts, Place de la Gare 16, Lausanne, Switzerland.

**I’m indebted to the art critic Roberta Smith for my subtitle. “When He was Good, He was Stunning” was the title of her January 10, 2020 New York Times review of Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Thank you for subscribing, reading, sharing, and commenting. I’ll be back soon with more art. Happy New Year!

Really fascinating how Vallotton's use of complementary colors in his nudes deliberately undermined viewer expectations. That unsual red-violet and greenish-yellow combo in The Purple Hat feels almost antagonistic,which completely breaks from the seduction typically baked into that genre. I dunno if many artists at the time were actively working against their own subject matter like that. Reminds me of how some modernists started treating beauty as suspect rather than the end goal.

Happy New Year, and oh, do you ever bring the New Year in with the most glorious of fireworks! Since I first spotted Vallotton—not so long ago—I have been drawn to his work whenever I see it. Your essay offers a plethora of reasons for that response. Those prints are astonishing, just as one example (and all of them are new to me, as is true of most of your selections). Thank you so much for this gorgeous essay, and welcome back!