I believe in art. … I believe in the Energy of art, and through the use of that energy, the artist’s ability to transform his or her life, and by example, the lives of others. – Audrey Flack (American, 1931-2024)

Audrey Flack, American visual artist, writer, banjo player, and feminist, passed away at the age of 93 on June 28, 2024. The statement above is an excerpt from a Commencement Address at Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, in May 1974 and is identified as the artist’s Credo on her website. Flack maintained her idealistic belief in the power of art throughout her life.

I first encountered Flack’s art as an undergraduate when I encountered Strawberry Tart Supreme in the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College. I recall this large Photorealist canvas almost jumping off the wall to engage my attention – and my sweet tooth. Photorealism was the latest avant garde movement to attract young artists and was largely a reaction against the emotional Abstract Expressionism and the mechanical Minimalism Painted in 1974 and acquired by the museum the same year, this work epitomizes the artist’s approach to Photorealism. In common with most of the movement’s artists, Flack worked from a projected photograph, used an airbrush to minimize texture, and created a surface as smooth as a photographic print. The similarity to a photograph is enhanced by the flat gray border that surrounds the image of pastries, intensifies their already bright colors, and stresses the artificiality of the image.

Flack was born in New York City in 1931. Her parents were Polish Jewish immigrants who were not enthusiastic about their daughter’s chosen career, though she had decided on it at an early age. The artist studied first at the Cooper Union and the transferred to Yale to complete her degree. At Yale, she studied with Josef Albers (German-American, 1888-1976), one of the most important painting teachers in United States history. Like many artists in New York City in the early 1950s, Flack started out as an Abstract Expressionist. (For more on Abstract Expressionism, see Chance Encounters 23.) Black Graph (1951), like many of her works from this period, suggests a layered, tiled environment of shallow depth. The graph-like patterns in this painting almost look like windows seen through dark foliage.

By the end of the 1950s, Flack had abandoned Abstract Expressionism for a representational style known as New Realism (Nouveau Réalisme). Dance of Death (1959) is an example of the artist’s painterly realism of this phase of her career. It also demonstrates Flack’s fascination with art history and some of the great artists of the past. The artist recalled how her home had been filled with reproductions of famous artworks which as a child, she had thought of as her friends. Flack studied art history at the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University and her love of the great artists of the past became increasingly important as her career progressed. The theme of the danse macabre or dance of death is one which dates back to the late Medieval period (early 14th century) and was intended as a memento mori, a reminder of mortality. This painting is an early example of Flack’s interest in the memento mori tradition in art. A bagpipe-playing winged skeleton plays at left while two female figures painted with warm tones are embraced by two male figures in greenish colors. The nudes’ poses refer back to the Classical tradition of the Three Graces in which the artist depicts female figures from a front, back, and three-quarters view. The women’s body types refer to those painted by Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577-1660), the Baroque artist whose preference for weighty women gave rise to the term Rubenesque.

In the early 1960s Flack began painting from photographs for the first time; according to some scholars she was the first artist to do so. Beginning with photos of her two daughters whose portraits she painted from her own photos, the artist then turned to using news photographs, both contemporary and historical. Flack’s next subject was architecture; from her own photographs, she depicted famous buildings like Brunelleschi’s Dome in the skyline of Florence and the Leaning Tower of Pisa. Around the same time, she created a series of paintings based on the polychrome (colorfully painted) sculptures of Spanish Baroque artists, especially those known or thought to have been created by Luisa Roldán (Spanish, 1650-1706). Macarena of Miracles (1971) is based on the 17th century sculpture Macarena Esperanza (the Virgin of Hope of Macarena) which is located in the Basilica of la Macarena in Seville, Spain. Current scholarship attributes this sculpture to Luisa Roldán’s father Pedro but it has also been attached to the daughter and this, along with the dramatic representation of the weeping Virgin Mary, drew Flack to the work. It is fascinating to me that an artist who was Jewish incorporated so much intensely emotional, Baroque Catholic imagery into her own paintings. The artist explained that she identified with Mary as a Jewish mother whose despair over the death of her son embodied the grief she herself felt as a mother of an autistic child who never learned to speak.

Mary in art screams silent screams of agony. I’m sort of Mary. A woman of sorrow for my sorrow. – Audrey Flack

Wheel of Fortune (Vanitas), completed in 1978, is an example of the Flack’s best known type of Photorealist work. “Vanitas” refers to a work of art which uses symbolism to demonstrate the fragility of life and the futility of wealth and pleasure. It was a popular underlying theme of still life, especially in the Baroque period, which was Flack’s favorite. Traditional symbols in this work that are common in vanitas compositions include the skull, suggestions of the passage of time – the burning candle, calendar, and hourglass, and gambling tools like the die and the Wheel of Fortune depicted in the tarot card. In addition to these traditional symbols are modern beauty tools like mirrors and makeup and the photograph of a young woman. This eight foot square painting doesn’t just hint at its meaning, it overpowers the viewer. Flack’s subject matter generally differs greatly from that of her Photorealist colleagues, almost all of whom are men. Like other male artists in the movement, Richard Estes (American, b. 1932), Don Eddy (American, b. 1944), and Ralph Goings (American, 1928-2016) depicted street scenes, automobiles, and motorcycles, mundane themes depicted with a distanced, impersonal quality. Flack’s works are autobiographical, dramatic, and filled with symbolism. In spite of this unusual characteristic, she was the first Photorealist artist to be collected by the Museum of Modern Art, when it acquired Leonardo’s Lady (1974) in 1975. (See that painting here.)

In spite of growing popularity with galleries, museums, collectors, and audiences, the Photorealists were not as popular with art critics. They were knocked for reproducing photographs, using airbrush technique, and their mundane subjects. Flack was described by New York Times critic Hilton Kramer as “the brassiest of the new breed” and in a late 1970s exhibition review, also in the Times, Vivien Raynor described the artist’s works as “horrendous” and vulgar. In a response, the artist wrote

The literal mindedness in my work that you refer to, is quite intentional, designed to reach an audience larger than the immediate art world … an audience that has been ignored and intimidated for many years. – Audrey Flack

In the 1980s, feeling that she had exhausted her Photorealist approach, Flack gave up two-dimensional work in favor of sculpture. Though she had trained extensively in painting and drawing, the artist was self-taught as a sculptor. From the beginning, Flack created larger-than-life sculptures of Classical goddesses like Athena and mythological figures like Medusa and Daphne. The artist also invented goddesses like the figures in the monumental gateway Civitas which she created for Rock Hill, South Carolina, a detail of which is shown above. Commissioned in 1988 and completed 1991, the gateway includes four 22-foot tall winged female figures, heroic statues signifying the ideals of the commissioning city: industry, knowledge, inspiration, and energy.

The artist’s creativity extended beyond her visual art. Flack took up banjo, attending a banjo camp in 2005, and then forming a band called Audrey Flack and the History of Art Band, which made some public appearances and recorded an album in 2012. The artist wrote lyrics about art-related subjects like Jackson Pollock, Vincent Van Gogh, and Mary Cassatt set to traditional American and bluegrass melodies.

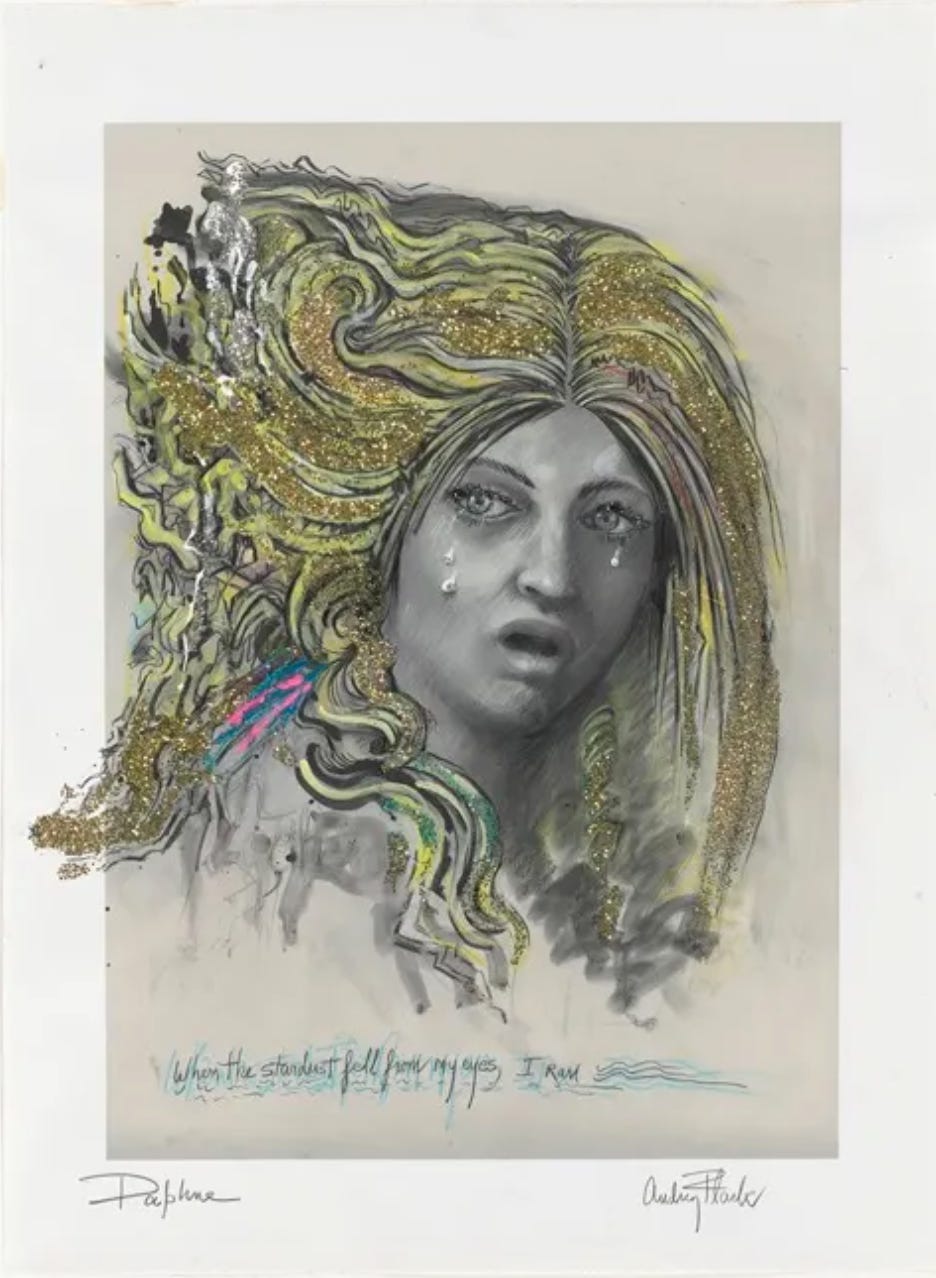

In the mid-2010s, Flack returned to two dimensional art combining all of her past interests: Classical mythology, popular culture, great artists of the past, and Baroque art, in an approach she called Post-Pop Baroque. When the Stardust Fell From My Eyes is a digital pigment print, that is, a digital photographic print, with mixed media additions. It depicts the mythological character of Daphne, a beautiful nymph who was pursued by the god Apollo. Just as he caught her, she cried out to her river god father to rescue her. He did so by transforming her into a laurel tree. Flack had depicted Daphne in sculpture and in this image, depicts the face three-dimensionally but monochromatically, so that the glitter and other materials stand out against the face and leafy hair. The inscription below the head reads “When the stardust fell from my eyes, I ran.” which seems to refer to the flowing lines of glitter. Unlike traditional depictions of the myth of Daphne which stress the dramatic chase and transformation of the nymph, in this work, Flack emphasizes the feelings of betrayal and fear experienced by the woman.

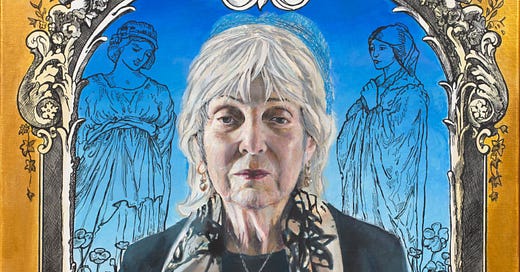

Throughout her career, Flack depicted herself in her works, both as herself and in the guise of some of her heroic female subjects. In Self Portrait with Flaming Heart, the artist combines her elderly image surrounded by symbols from a variety of periods and traditions. The flaming heart originates in Spanish Baroque images of the Virgin Mary; at the same time, the artist wears a Star of David pendant symbolizing her Jewish heritage. In the blue atmospheric space behind the artist are line drawings which resemble a Classical figure (on the left) and a Renaissance saint or praying figure (on the right). In the upper right and left corners, the artist designed ornamental letters of her initials, making reference to the long tradition of ornamental lettering in art history. The decorative frame surrounding her portrait is ornamented with putti (baby angels), found throughout the Western art historical tradition; several carry stringed instruments and a lyre, a harp-like instrument is centered beneath the self-portrait. Another long tradition in art history is using musical instruments and musicians to symbolize other arts. At the top of the frame is the famous phrase “Ars longa, vita brevis” (art lasts long, life is short), a highly significant choice for an artist’s self-portrait painted after she has passed her 90th birthday. Throughout this late work, Flack incorporates details from her life and interests, blending them into a unified statement of her identity.

Artists always paint who they are. – Audrey Flack

Completed just last year, A Brush with Destiny uses Audrey Flack’s youthful face, in monochrome, in a complex composition. The central figure is shown in an ornate gown like those seen in Renaissance and Baroque portraits, but portions of her jeweled headdress and lace collar are not fully colored. To the left of the central figure is a line drawing of the Rococo portraitist Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (French, 1755-1842), best known as the favorite portraitist of French Queen Marie Antoinette. In one hand, the French painter holds a brush with which she adds yellow to the central figure’s earring; in the other hand are more brushes, each with a different color. To the right of the central figure a line drawing of Abstract Expressionist Jackson Pollock (American, 1912-1956) who drips blue paint from a brush in one hand and blue and red paint from a can in his other. These two painters represent Flack’s life as an artist; her feminism, interest in illusionistic realism, and technical precision are expressed by Vigée-Lebrun while Flack’s early training and work as an Abstract Expressionist are signified by Pollock. I’m still working on the symbolism of the rose and leafy plant held by the central figure and the line drawing of the Houses of Parliament of London, but as is so often the case in Flack’s work, there are more details to be discovered and considered.

Art is a calling. Artists are not discovered in school. Artists do not just paint for themselves, and they don’t simply paint for an audience. They paint because they have to. There is something within the artist that has to be expressed . Every creation reveals something more about the universe and about the artist.” – Audrey Flack, from Art & Soul: Notes on Creating

Audrey Flack spent over 70 years creating art according to her unique vision of art as self-expressive and transformational. From her beginnings in Abstract Expressionism to her final Post-Pop Baroque creations, she provided absorbing works which reward deep exploration. If her work is new to you, I hope I’ve inspired you to explore more of an artist who inspired me as a student many years ago.

See more of Audrey Flack’s work:

Artist’s website: http://www.audreyflack.com/

Online memorial exhibition (ongoing): https://www.meiselgallery.com/exhibition/audrey-flack-in-memoriam-1931-2024/

Upcoming exhibition: Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, New York, USA, Oct 13, 2024 – Apr 6, 2025 https://parrishart.org/exhibitions/audrey-flack/

Hollis Taggart Gallery, New York, New York, USA: https://www.hollistaggart.com/artists/35-audrey-flack/

Thank you for sharing this!

I think I may have enjoyed reading about and seeing some of her work more than any of you other posts here.THANK YOU FOR SHARING THIS WITH ME.