In this edition of Chance Encounters, I am presenting a very brief history of collage, a technique which entails creating an image or pattern by attaching various materials together in order to produce a new whole. The name comes from the French coller meaning “to paste” or “to stick together.” Of the methods of art-making, the collage technique is one of the most familiar beyond the art world. At least once during our school years, most of us have pasted bits of paper and printed images together to make an image. Two-dimensional collage inspired a sculptural variation, assemblage. There are analogous concepts in the visual arts of architecture, film, and fashion. Collage-like techniques have also been used in music and literature.

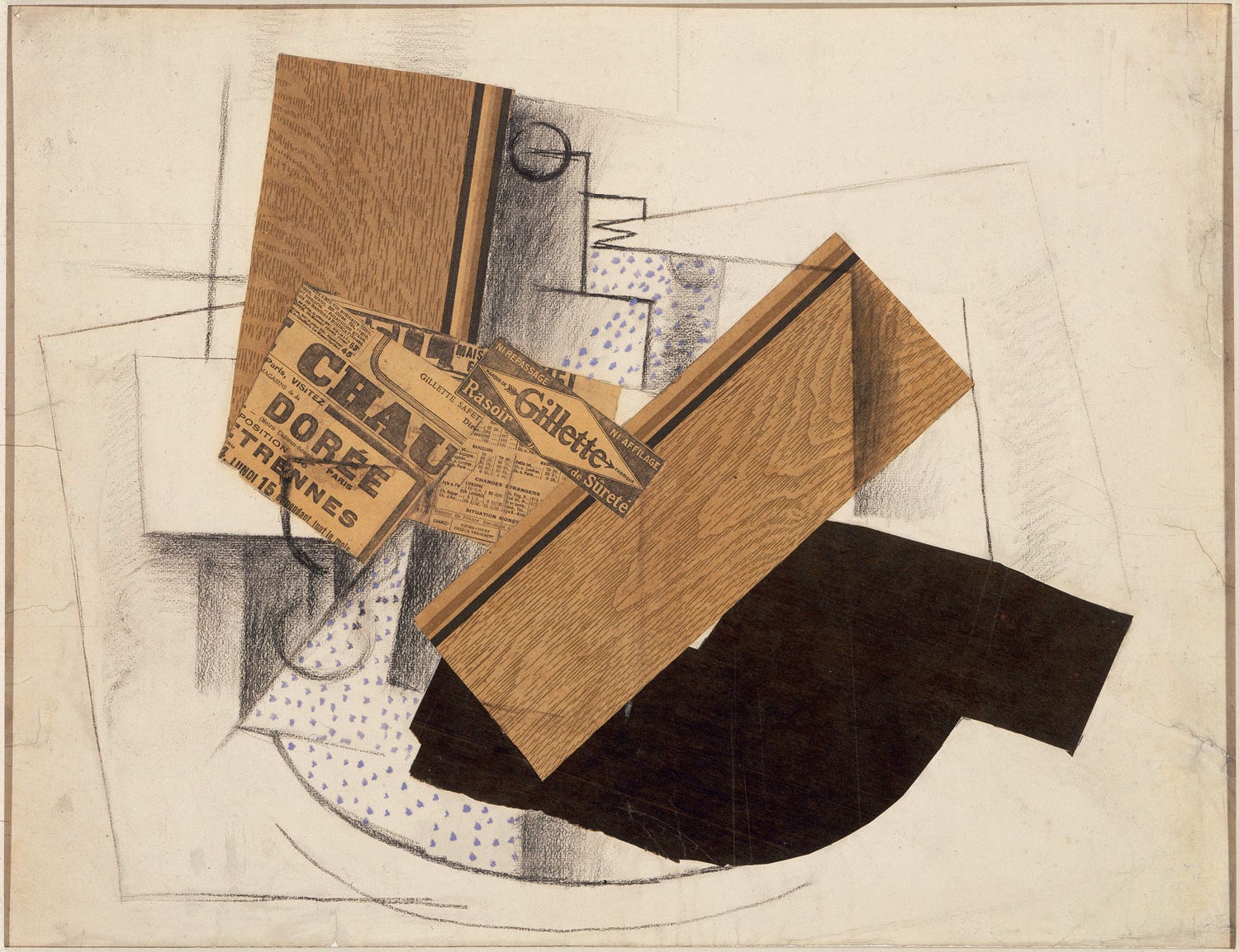

Georges Braque (French, 1882-1963) and Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973) are traditionally credited with introducing collage into the art world. During the Cubist movement, around 1911, these artists began to experiment with pasting together bits of newspaper, colored paper and their own drawings. Braque is thought to be the first to create paper collages, or papiers collés as the artists called them, while Picasso was the first to incorporate collage into oil painting. (For discussion of one such work, Still Life with Chair Caning, ca. 1911-1912, see Chance Encounters 11.) Still Life on a Table (Gillette), above, is an excellent example of Braque’s collages. The artist’s acquisition of a roll of wood-grained wallpaper inspired his first efforts in collage. The contrast of hand-drawn (or painted) forms with illusionistically printed materials like this wallpaper attracted the Cubists because it allowed them to play with texture and to confound the viewer’s sense of reality. In this work, the drawing both underlies the applied papers and overlaps them; the pieces of wood-grained wallpaper imitate the material of a table and the bits of newsprint stand in for a whole newspaper that might have been left on that table. The drawn glass, shadows, and polka-dot pattern suggest more of the tablescape, and the whole is depicted in the Cubist manner which attempts to indicate all objects from multiple vantage points at the same time. The collages provided a transitional phase between the two phases of Cubism, Analytical and Synthetic. The added materials in Cubist collage showed the artists how larger blocks of pattern or color could create greater self-expression while maintaining the basic philosophy of Cubism, the restructuring of reality. As a result, Braque and Picasso began using painted planes of color and pattern according to their own tastes.

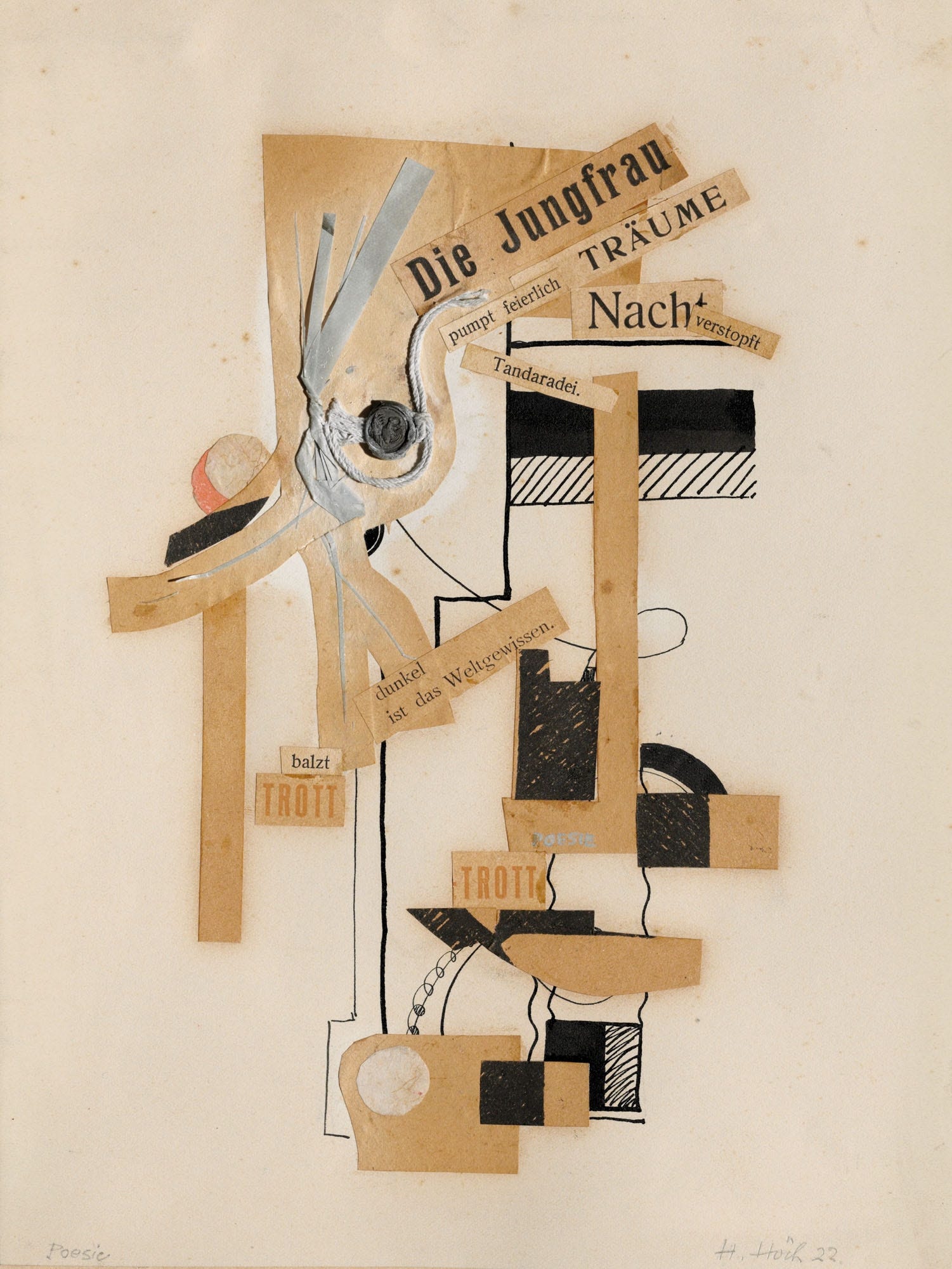

Collage turned out to be a flexible technique which spread rapidly within the European avant garde. The technique is well suited 20th century artists’ desire to challenge tradition, incorporate popular culture, and break down barriers between drawing, painting, and sculpture. Many artists of the Dada movement were drawn to collage for the opportunity to challenge orderly communication of information. Breaking with society’s traditions was a primary goal of Dada artists. Faced with the social disfunction and political violence leading up to and during World War I, Dada responded with art based on impermanence, irrationality, and ironic humor. A leading collagist of Dada, Hannah Höch (German, 1889-1978) is best known for her photomontages, collages utilizing printed images, a technique of which she is considered a pioneer. Poesie (Poem) is a clever combination of collage and the artist’s original poem, in spite of the absence of her signature technique. Commercially printed words are common in Dada images; in this case the artist has collected the words of her poem which lead the viewer from top to bottom in her composition. The text reads

Die Jungfrau

pumpt feierlich Träume

Nacht verstopft

Tandaradei

dunkel ist das Weltgewissen

balzt Trott Trott

The Virgin

solemnly pumps dreams

clogged at night

Tandaradei (an onomatopoetic word for bird song)

the world’s conscience is dark

courtship Trott Trott

The onomatopoeia and closing nonsense word repeated are typical of Dada poetry which uses such devices to disrupt comprehension in the same way that the overlapping words and changing font sizes make the poem hard to follow in the collage. Höch ties her collaged materials to the drawn elements by relating shapes (mostly rectangular) and lines (the string and the wiry drawn lines). On the other hand, the mechanical imagery of the collage contrasts with the images conjured by the poem, leaving the viewer to reconcile the two. Such a challenge to the observer is a characteristic Dada strategy, with the goal of breaking one’s attachment to societal traditions.

Another artist closely associated with the Dada collage tradition is Kurt Schwitters (German, 1887-1948). During World War I, the artist’s style was characterized by the anxious and often pessimistic approach of the Expressionist movement. After the war, Schwitters came into contact with the Berlin avant garde which included many German Dada artists, Hannah Höch among them. Schwitters began creating collages around 1918, works he termed Merz, after a bit of text cut from the word Commerz (commerce). He expanded his Merz approach to incorporate three dimensional assemblage and architecture, gradually adding three dimensional structures to his home, which he called the Merzbau. (The Sprengel Museum in Hanover, Germany exhibits a reconstruction of Schwitters’ first Merzbau which was located in his family’s home in that city.) In the 1920s and 30s, the artist experienced success but like so many avant garde artists in Germany, Schwitters fell under the displeasure of the Nazis and his works were incorporated into the Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition. In early 1937 Schwitters chose to flee Germany, after being summoned for an “interview” by the Gestapo. The artist never returned to Germany. When the Nazis invaded Norway, Schwitters and his family escaped to Britain where the artist was interned, first in Scotland and later on the Isle of Man where he spent over a year.

For this edition, I’ve chosen a later work by the artist, Untitled (The Hitler Gang) made around 1944, which demonstrates how early ideas and techniques continued throughout his career. In this collage, printed materials include: a bus or train ticket that includes “London” where he was living at the time; a target-like illustration; an advertisement for the 1944 film “The Hitler Gang” from which the work’s alternate title derives; a crumpled bit of newspaper which includes the word “Nazis;” and what appears to be an excerpt from a palm-reading manual.

Your Hand denotes … rather masterful nature, … haughty, not fond of being told how to do things, and prefer to be a master … than a servant. – printed text attached to right side of Untitled (The Hitler Gang), ca. 1944 by Kurt Schwitters

I wonder whether the artist intends this to refer to Hitler or himself. The ambiguity and potential humor is typical of Schwitters’ works. One more detail to which I want to call attention is the fragment of material printed with a chair-caning pattern. This likely refers to Picasso’s important collage painting Still Life with Chair Caning (see link above). For Schwitters, the ideas referenced in this collage were momentous experiences in his life, his adoption of the collage technique, the rise of the Nazis, and this stage of his life in London (1940-1945).

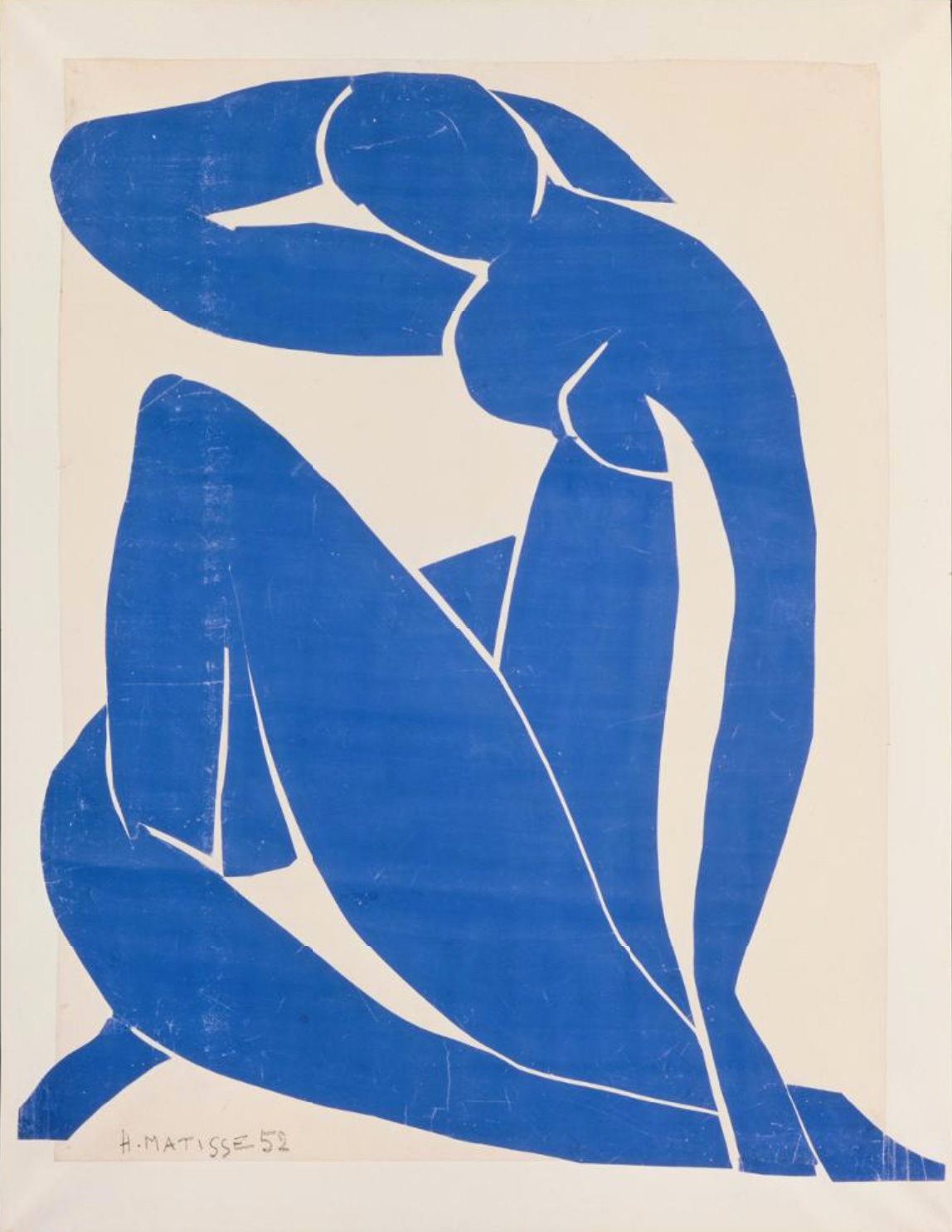

As with Kurt Schwitters, this work comes from later in the artist’s career. By 1952, Henri Matisse (French, 1869-1954) had been a professional artist for almost 60 years. He had painted and sculpted in several styles, notably as a founding member of the Fauve movement. (For more on that movement, see See Chance Encounters 22.) In 1941, Matisse was diagnosed with abdominal cancer, undergoing surgery which left him confined to a wheelchair or his bed. The artist, who described discovering “a kind of paradise” in making art, was undeterred, inventing a new approach to collage that he could manage in his new circumstances. The technique, which Matisse called decoupage and which is called “cut out” in English, involved the artist cutting shapes from paper which had been painted in bright colors by his assistants. (See video below.) The shapes would be arranged on a support, either by the artist or under his direction and then pasted in place. Sometimes the artist would pin the composition to the wall to live with it and make changes until he was satisfied. Matisse had used a similar technique earlier in his life when he’d been creating sets and/or costumes for opera (1919 and ballet (1937-1938) productions. These designs were preparatory in nature, unlike the works of the 1940s and 50s. Blue Nude II is one of a series of cut outs and associated lithographic prints that Matisse created in the 1950s; he was still at work on the series at the time of his death in 1954. The first of the 4 cut outs took two weeks and a notebook full of studies before the artist was satisfied; Blue Nude II shows the pose that Matisse settled on, an undulating arrangement of intertwined limbs. This unique approach to collage provided the artist with a new mode of expression when he really needed it; Matisse said his last fourteen years were “une seconde vie” (a second life).

A brief film of Henri Matisse at work on a cut out.

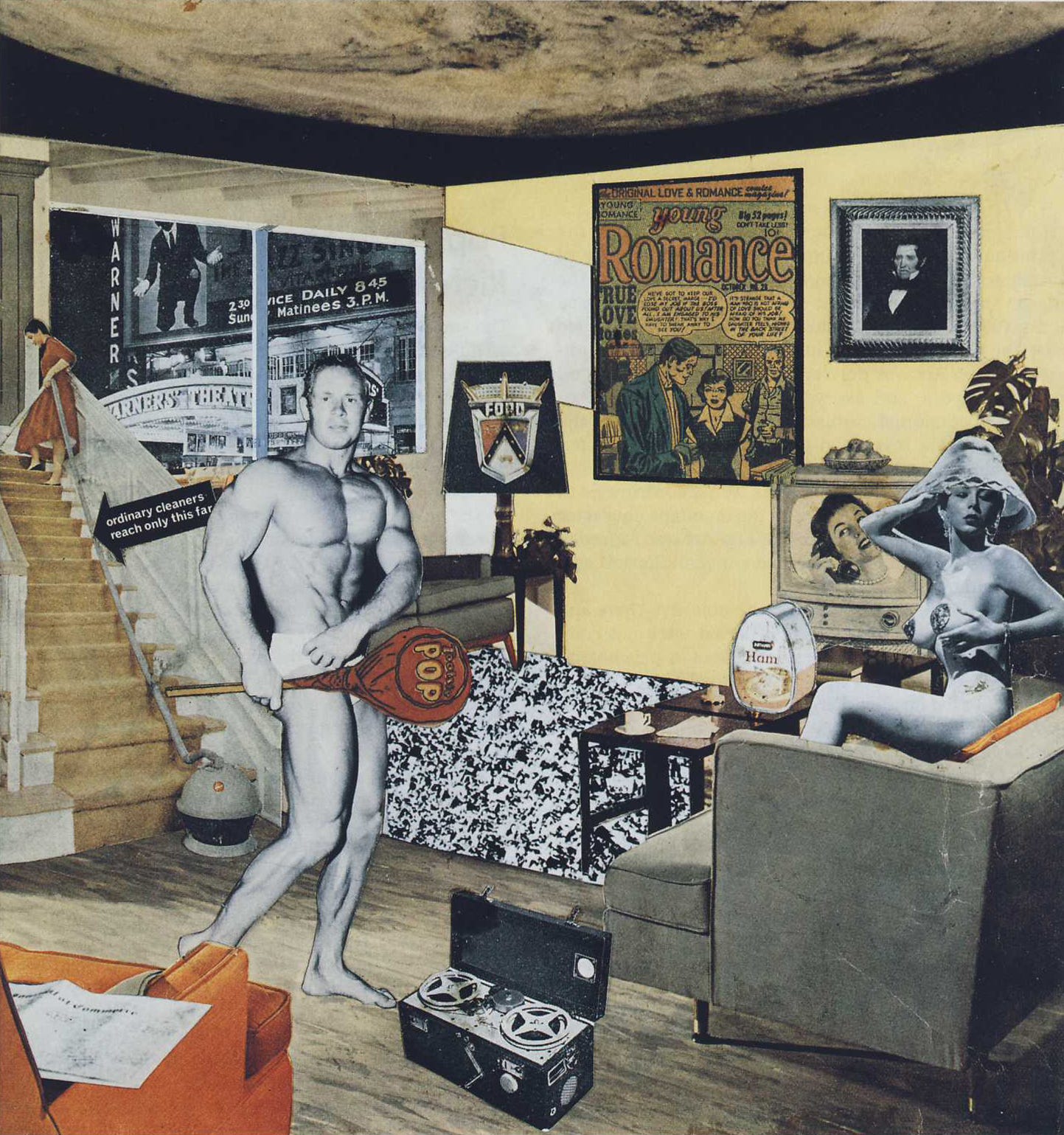

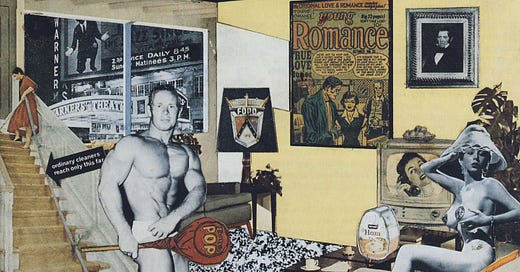

Just a short time after Matisse’s death, the Pop Art movement was beginning and this collage by Richard Hamilton (English, 1922-2011) is a founding monument of that movement in spite of its small size. Just what is it that makes today's homes so different, so appealing? is a photomontage focusing on advertising images of post-World War II luxuries. In a living room, a body builder holds a Tootsie Pop like a barbell while a burlesque queen poses on a mid-century modern sofa. A reel to reel tape recorder and a television showing a woman with a telephone demonstrate the latest media technology, while an ad for an extra-convenient vacuum cleaner demonstrates the ease of modern life. A Ford Motors logo ornaments a lampshade and the marvel of a canned ham sits on the coffee table. On the wall hangs a cover from a comic book, a popular form of entertainment in the period. In contrast to all this modernity are the Victorian gentleman watching in disapproval from the photograph on the wall and the newspaper, the traditional source of information, in the lower left corner. Outside the window is a movie theater marquee advertising the first motion picture “talkie,” The Jazz Singer of 1927. It’s a black and white image in contrast to the colorful interior, perhaps to suggest its role as an older medium but also one which preceded all the new technologies on display in the foreground. The images all came from American magazines which the artist had received from a colleague studying in the U.S. A painter as well as collage artist, Hamilton had a strong interest in understanding the evolution of popular culture in addition to exploring it in his visual art. This interest led to his fascination with Hollywood and advertising, about which he lectured, as well as incorporating it into this collage and other works. Never losing his fascination for the latest technologies, Hamilton experimented with new materials throughout his career, working with plastics, electronics, and eventually, computer technology including Photoshop.

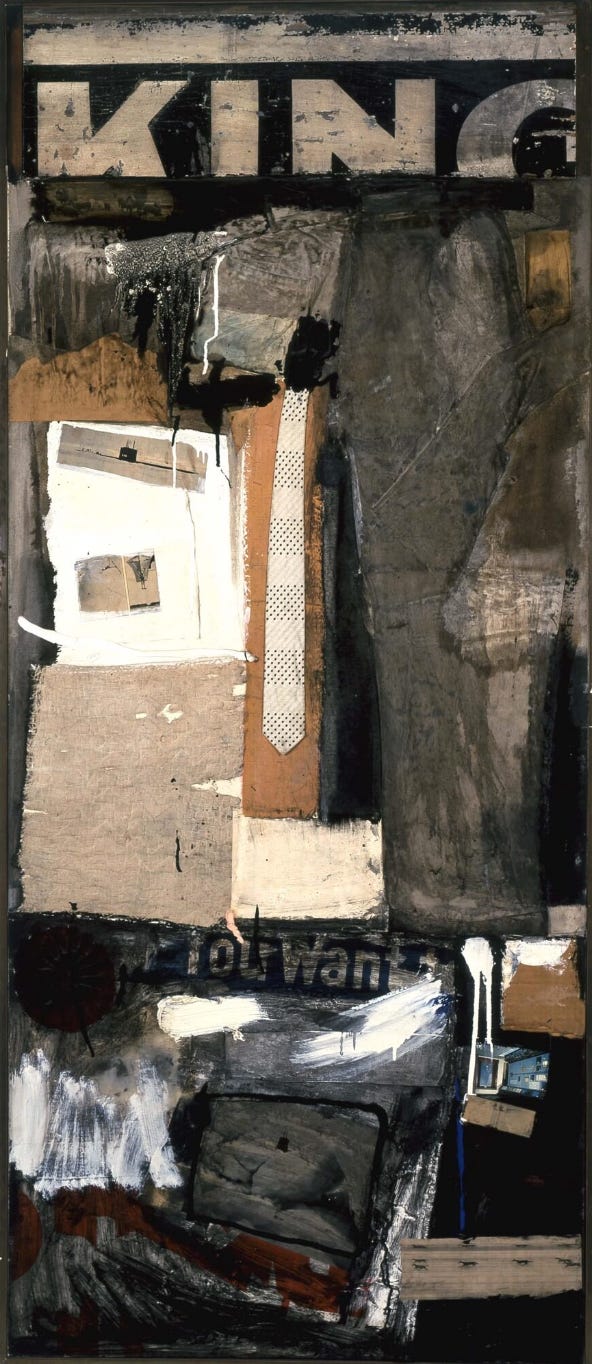

Like others before him, American artist Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008) took the idea of collage and added his own twist which he termed the Combine. Consisting of painted and collaged supports mixed with found objects, the Combines mix the traditions of two-dimensional and three-dimensional art. Sometimes described as Neo-Dada, Rauschenberg’s work with found objects questioned the distinction between art and everyday objects as Dada artists like Marcel Duchamp (French, 1887-1968) had done in the early 20th century. An example of Rauschenberg’s Combines, Kickback uses traditional collage elements like printed images, paper, and fabric, along with abstractly painted areas and an attached necktie, pant leg and found wooden sign. Exactly how the varied elements are connected isn’t clear; as in original Dada, the apparent chaos and irrationality is meant to challenge tradition and the viewer’s attachment to those traditions.

I wanted something other than what I could make myself and I wanted to use the surprise and the collectiveness and the generosity of finding surprises. And if it wasn’t a surprise at first, by the time I got through with it, it was. So the object itself was changed by its context and therefore it became a new thing. – Robert Rauschenberg, quoted in The Symbolist Roots of Modern Art, 2015 (Michelle Facos and Thor J. Mednick, editors)

Like Richard Hamilton, Rauschenberg’s interests led to experimentation in visual arts of many types including printmaking, photography, papermaking and performance art. He also became involved in dance, initially designing sets, lighting and costumes but eventually choreographing performances too. He was associated with important American dancers, choreographers and musicians including Paul Taylor, Merce Cunningham, and John Cage. Rauschenberg is an artist for whom the flexibility of collage is connected to a general flexibility of creative thinking.

As the years of the 20th century passed, the availability of diverse imagery, first printed and then electronic as well, has proved a treasure trove for collage artists. Romare Bearden (American, 1911-1988) grew up in an African American family which was deeply involved in the Harlem community. His father was a musician and his mother was a New York correspondent for the black newspaper, The Chicago Defender; his family’s home was a gathering place for famous figures of the Harlem Renaissance. (For more on that movement, see Chance Encounters 35.) These experiences led Bearden to feel a strong sense of responsibility toward his community, not only through his art, but by actively working to organize with other black artists and by co-authoring art historical studies of African American artists. Empress of the Blues, though created in 1974, looks back to the period of the Harlem Renaissance in depicting Bessie Smith (American, 1894-1937) performing with a band. Much of the background is painted with acrylic paint embellished with printed papers, including Smith’s dress, sheet music and musical instruments. The vivid colors and abstraction are a tribute to the vibrant musical culture in the Harlem of Bearden’s youth. Bearden remained committed to collage throughout most of his career and at the time of his death was described by The New York Times as “the nation’s foremost collagist.”

Beginning in the early 1950s, Abstract Expressionist artist Lee Krasner (American, 1908-1984), began working with collage. She and Robert Motherwell (American, 1915-1991) were the only members of Abstract Expressionism to use the collage technique extensively. Dissatisfied with her recent works, Krasner cut and tore them to pieces, then used the pieces as components in her new collaged works. At the same time, she stopped working on an easel, creating the collages on canvases lying flat on the floor. Like Matisse, around the same time but an ocean away, she pinned the collage elements together until satisfied with the composition at which point they were glued down. The artist often added additional brushwork as a final stage. Krasner valued the uneven surfaces and varied textures that arose from her technique. To the North is from a later series of collages begun in the 1970s, this time using scraps and forgotten pieces found as she cleaned out her studio. Combining smooth paper used for old drawings with rougher canvas fragments added greater textural contrast in these later collages. The dense orange sections of To the North contrast with the blue paint spatters and streaks, the complementary colors intensifying one another and heightening the unpainted white sections. The flow of Krasner’s composition runs in curves from the upper left to the lower right, while a contrasting diagonal running from lower left to upper right is mostly buried beneath. Cut edges disrupt strokes and spatters of blue creating further tension between the different parts of the composition. As an Abstract Expressionist, Krasner was interested in exploring her emotions through her work and her collages are evidence of her self-critical approach and a desire to reassess her past works in light of later emotions and ideas.

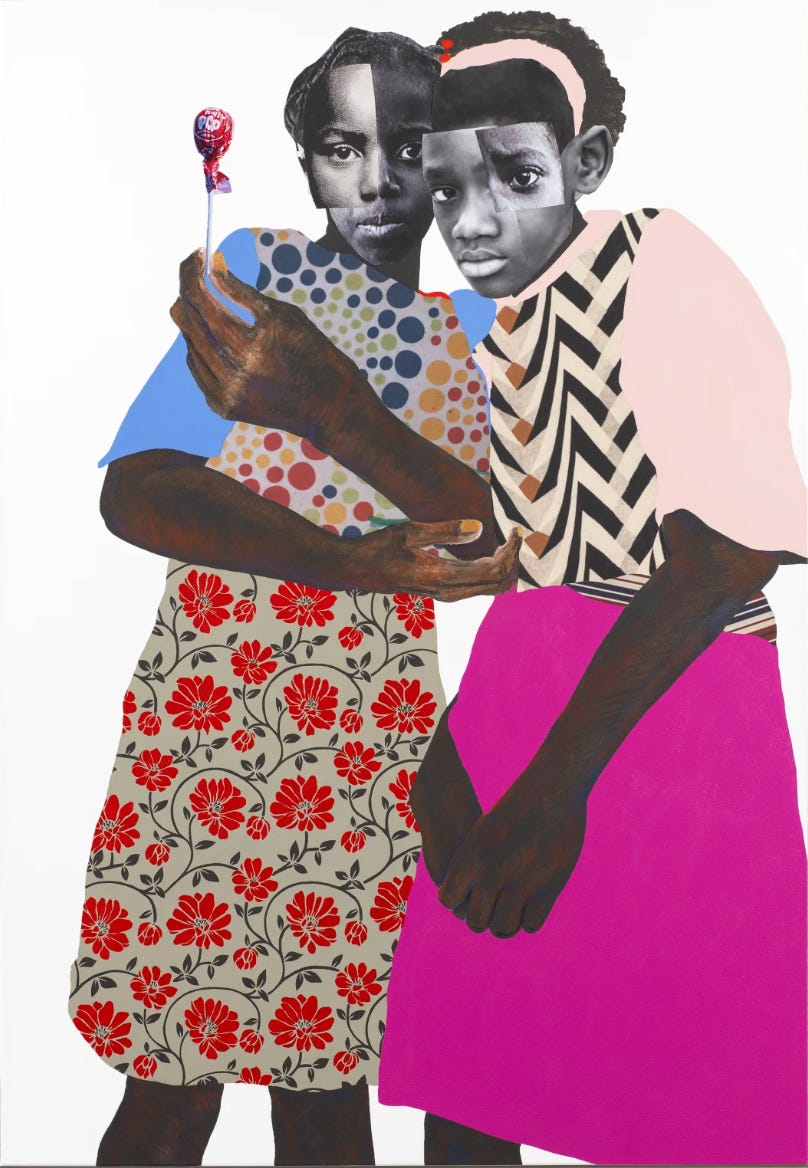

Collage continues to be a fruitful method for contemporary artists. The Unseen is one of many works exploring the world of African American young people by Deborah Roberts (American, b. 1962). The artist recognized ideals of beauty as presented by fashion magazines and art historical images devalued her own and her friends’ appearances. This led Roberts to seek a broader vision of beauty through her art, using collage as an expression of the multiple sources and possibilities of beauty in her subjects. In the current example, two young black girls express different personalities through pose and expression, but the faces created from fragments of different images suggest that these current identities aren’t fully established. The candy and brightly colored clothing convey a carefree childhood at odds with the outsized arms and the emotions expressed by the two faces.

With collage, I can create a more expansive and inclusive view of the Black cultural experience. -- Deborah Roberts

Roberts’ work is included in the current exhibition “Multiplicity: Blackness in Contemporary American Collage” at Phillips Collection in Washington, DC which includes 49 artists who have explored black identity through the use of collage. The artists in this exhibition are among the many contemporary artists worldwide who have found the flexibility of collage well-suited to their iconographic and aesthetic purposes. I’ve only skimmed the surface of the history of this fascinating medium; I might have to revisit it in the future.

Current exhibitions featuring collage:

“Collage Culture” at Monique Meloche Gallery, 451 N. Paulina Street, Chicago, Illinois through July 27, 2024. https://www.moniquemeloche.com/exhibitions/218-collage-culture/press_release_text/

“Multiplicity: Blackness in Contemporary American Collage” at The Phillips Collection, 1600 21st Street NW, Washington, DC until September 22, 2024. https://www.phillipscollection.org/event/2024-07-06-multiplicity

Wonderful article! Saving for art history studies later 😊

Wow! There is so much here to savor, and your way of bringing out so many details is fantastic. You teach us, among many other things, to take the time to observe all we can. Thank you so much for that. The Lee Krasner was a real surprise. Appealing on its own, but also offering an aspect of her work of which I had no idea (not that this is a measure of too much, as I know so little). Anyway, this is yet another of your posts to which I’ll likely return to learn more, dig deeper. (An aside: life intervened, and, to my keen disappointment, I was not able to get to the either Thiebaud or Pankararu exhibits. So near, and yet so far!)