Chance Encounters, Edition 33

The Methods Behind the Madness, 100 Years of Surrealism, part 2

This is the second in a series examining Surrealism in honor of its hundredth anniversary. (Part 1 of the series can be found here: Chance Encounters 26.) Exhibitions are being held around the world throughout this year and into 2025 in celebration. Available information about current and upcoming events is included at the end of this post.

My subject today is some of the techniques used by Surrealist artists to create their art. Surrealist theory dictated that the goal was to combine conscious reality and subconscious reality in order to create surrealité, an absolute or superior reality. The practical question each visual artist faced was how to achieve this in a painting, drawing, or other object. The answers were as varied as one might expect from a movement which stressed the individuality of the practitioner’s psychology.

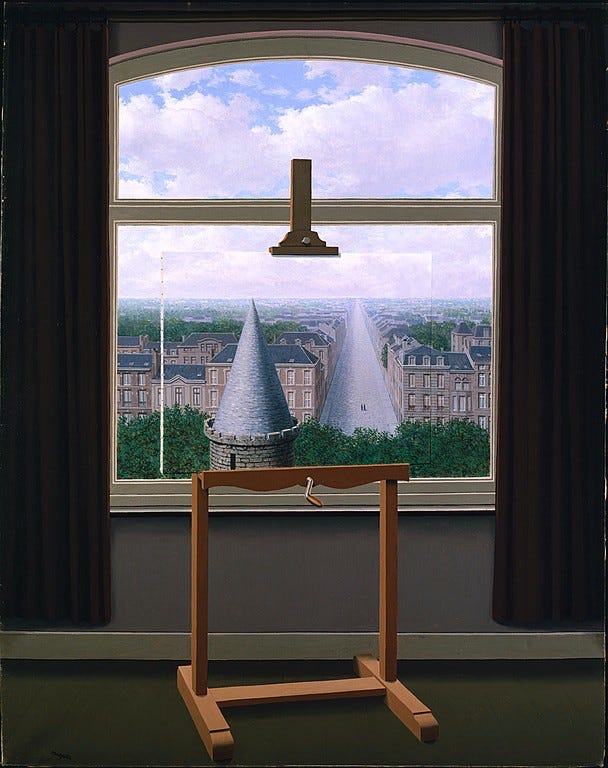

Surrealist artists who used illusionism, like Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989) or René Magritte (Belgian, 1898-1967), adapted tools of naturalism which had been used in European art since the Renaissance. Magritte had joined the Belgian Surrealist Group at its founding in 1926 and met many of the leading Surrealists in Paris not long after. The artist’s main interest was in the nature of reality and how people use language to understand or interpret it. In The Promenades of Euclid, we recognize the room and curtains, the window frame and the view through the window, because the artist has used life-like color, scale and proportion, contrast of light and shadow, and single point linear perspective, just as other painters had done before him. Magritte loved creating puzzles with his works though, so things aren’t always what they seem. In this example, we feel we’re looking at something completely ordinary until we realize the “view” through the window is at least partially a painting. The wooden object in front of the window is an easel and we can make out the tacked edge of unpainted canvas on the left; the other three sides are faint lines cutting through the scenery. Magritte isn’t finished playing with our sense of what is real however. The road that recedes toward the horizon is a mirror image of the tower roof to its left. Only a slight difference in texture, the roof’s darker colors, and a pair of tiny pedestrians on the road distinguish the two objects. We must also consider Magritte’s title, where the artist often played word games with the viewer. The reference to Euclid, the ancient Greek whose geometry we all recall from high school, may point to the visual play of the cone of the roof and the triangle of the road, but the whole work is constructed of sharply defined geometric forms with the exception of the organic treetops and clouds. Is the painting itself a promenade of Euclidean shapes? Or does “promenade” refer to the two small walking figures? To the path-like road and tower roof? In the end, it’s up to the viewer to decide. Magritte’s illusionistic tools create a believable world, but the longer you look, the less certain reality seems to be.

Many new methods of mark and image making were invented by Surrealist artists, used mainly, but not exclusively, by those creating abstract rather than illusionistic art. Above all, they were looking for techniques of automatism – that is, introducing chance-made marks that would spark increased creative freedom. In the Surrealist Manifesto, André Breton (French, 1896-1966) had defined Surrealism as “pure psychic automatism.” The conscious and rational aspects of the mind had to be short-circuited by the use of automatist techniques in order to achieve the kind of literature and art that the Surrealists wanted. In the visual arts, automatic drawing and painting led to the creation of unique abstract images or served as a starting point for artists. Joan Miró (Catalan Spanish, 1893-1983) used automatic drawing and painting as an important element in his art. Miró would use the marks created using these techniques as the basis for his compositions, combining the elements produced by his subconscious reality (as the Surrealists considered automatist creation) with consciously created imagery to make the finished work. Miró’s approach resulted in a literal surrealité. In The Red Sun, the artist used automatic painting to produce a thick black circle and drizzled curves and droplets of black paint down the three foot tall canvas. Miró then expanded upon the black marks, painting a floating head in the black circle, a carefully delineated standing body at right and a second creature made from the lower group of dripped marks combined with a biomorphic shape with a green and red eye. The large red oval at the left gave the painting its title. The artist created a hazy background of blues and grays that implies depth, but is also more suggestive of night than day. The blue area, along with the mist of green and yellow, may be meant to connect the floating head with the standing body, but as is so often the case with Surrealist art, there are as many possible interpretations of what is depicted as there are interpreters.

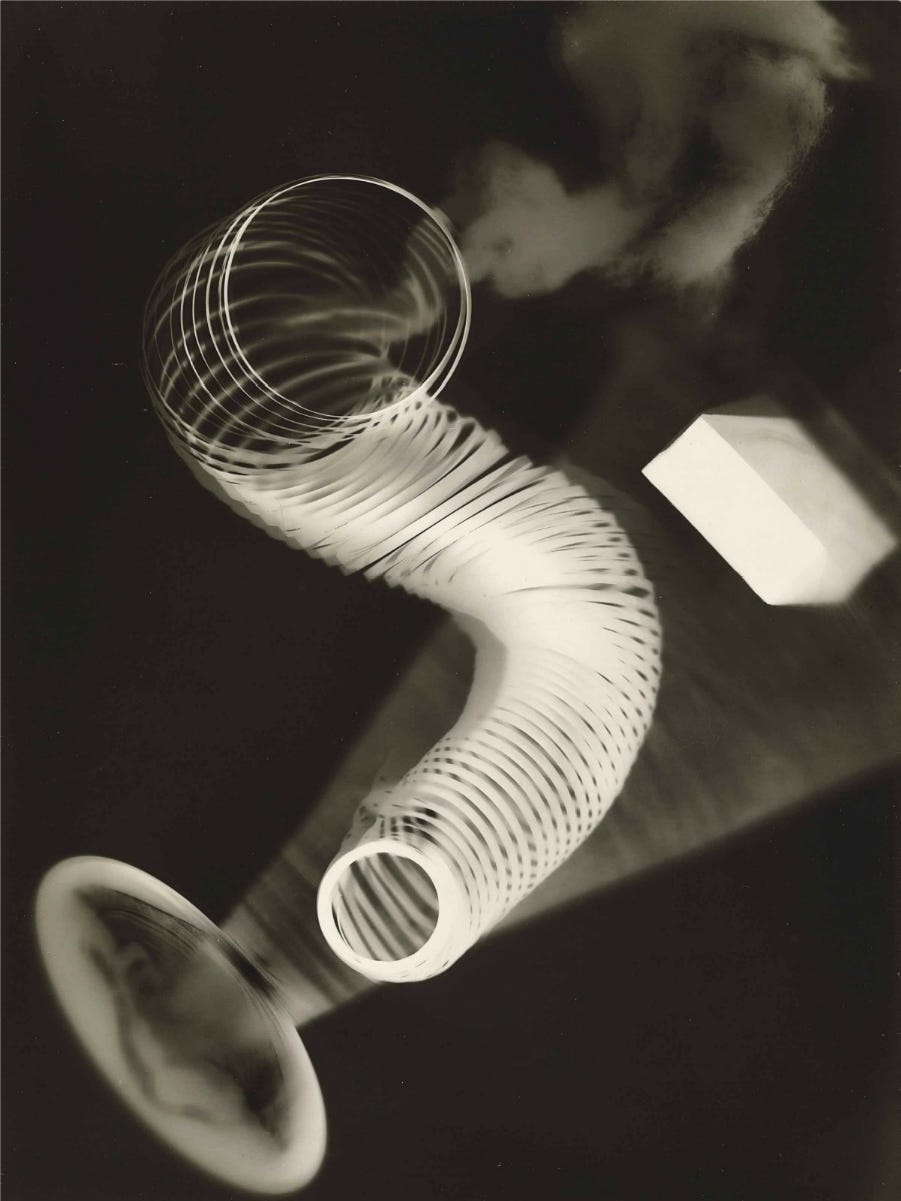

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976) developed an approach to photography which he called the rayograph, a cameraless method known as the photogram. As a young artist in search of a radical avant garde, Man Ray found the Dada movement through meeting Marcel Duchamp in New York City around 1915. Dada flourished during and immediately after World War I among young artists, many displaced by the war. The Dada artists wished to undertake a critical re-examination of the concepts of order and beauty and the rules that had guided the creation of the arts in Western culture. In that re-evaluation, they concluded that only irrationality and anarchy would usher in the new era they were seeking. During the 1920s, many of the Dadaists moved on and joined the Surrealist movement, bringing with them a taste for wordplay, games, and satire. Where the Dada movement had been characterized by playfulness and a focus on changing society, the later movement was often intense and far more interested in the psychology of the individual creator and consumer of Surrealist creativity. Still, the idea of games and other efforts to incorporate chance through automatism were brought into Surrealism by the former Dadaists. Man Ray, who arrived in Paris in 1921, soon found his way into Surrealist circles. Though the rayographs incorporate Dadaist chance into his process, they also produce the mysterious and difficult to interpret imagery that Surrealists valued.

I have finally freed myself from the sticky medium of paint, and am working directly with light itself. — Man Ray

Though Man Ray wasn’t the originator of the photogram (some of the inventors of photography had used the technique in the 1830s and 40s), he used it effectively in creating Surrealist images. This method has the artist place objects on light sensitive photographic paper which is then exposed to light. Objects of varying transparency create the most compelling results. In the example here, the coiled object and the white rectangle allowed no light to reach the paper so they appear white. The objects that appear more distant were more translucent so they appear in varied tones of gray. The artist can place objects in different groupings on the same paper, exposing them to light sequentially in order to produce the illusion of depth like Man Ray achieved here. As a result, the amorphous material at the top right appears to be emanating from the circular mouth of the coil and the composition begins to suggest connections within itself and to worlds both real and fictional.

American Surrealist David Hare (1917-1992) is best known for his sculptures but his earliest forays into art and Surrealism involved photography. He developed a method of heating photographic negatives from below which created random distortions of the image. He called his technique heatage; in French, it is known as brûlage. Around 1942, Hare made several prints from a negative showing a seated nude woman, mounting some on colored paper and playing with dark room effects that added color to the image or deemphasized the platform on which the woman sits. At first glance the effect appears similar to solarization (also known as Sabatier effect or pseudo-solarization). This technique was discovered by the Surrealist photographer Lee Miller who had accidentally turned on a light while developing a photograph causing the photograph’s lighter areas to turn black. Carefully controlling this solarizing effect creates an image with strongly defined black outlines while interior details remain clear. The result has the combination of the real and the uncanny that many Surrealists sought which explains why Miller and Man Ray used it regularly. (See an example at this link: Solarized Portrait (1930) by Lee Miller.) In contrast, heatage treats the negative and has a more random effect on areas of light and dark, thus Hare’s method was a more effective tool for introducing automatism into photography.

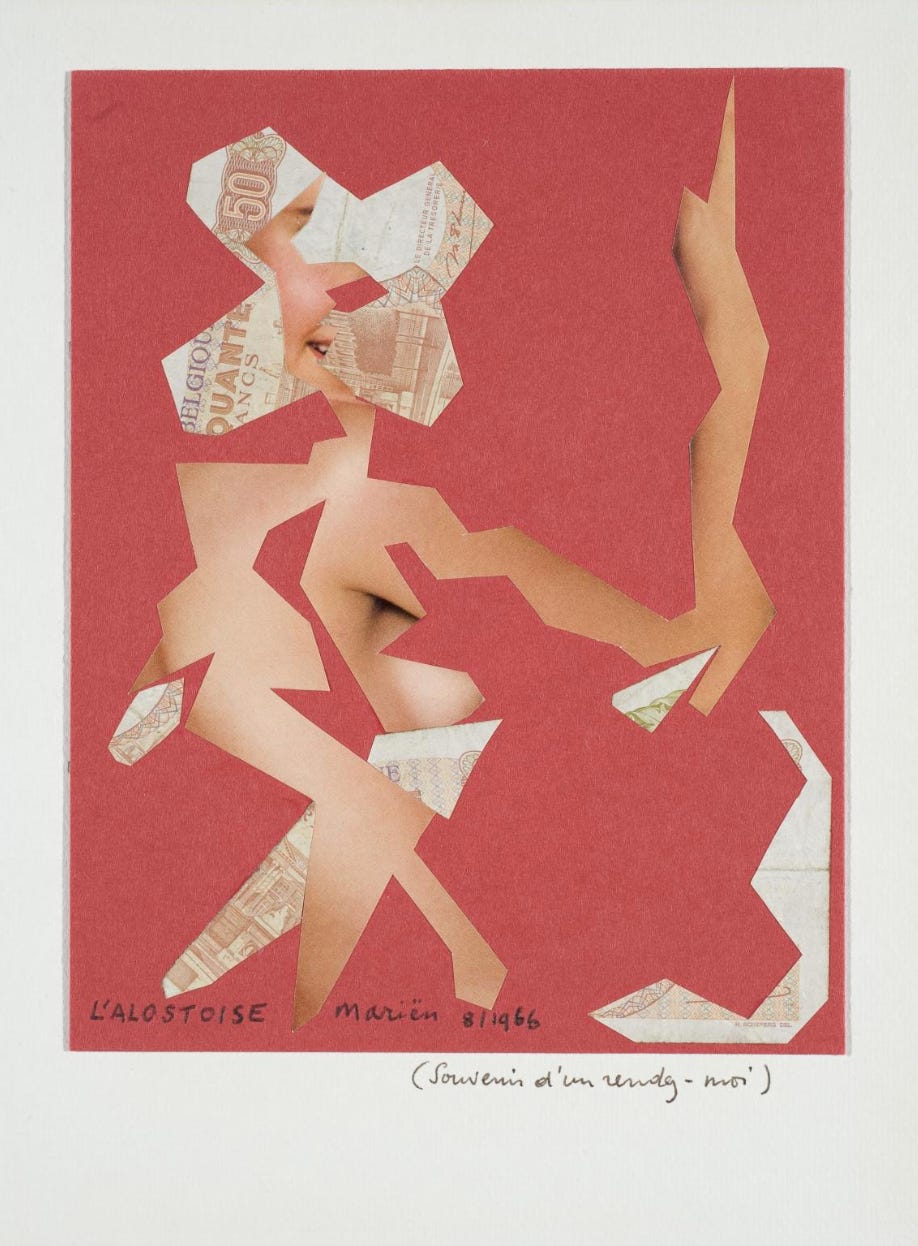

Collage was used first by the Cubists George Braque and Pablo Picasso in the 1910s (See this earlier edition for more on Picasso and collage Chance Encounters 11) and was enthusiastically adopted by Dada artists. Collage’s combination of destructive and constructive qualities appealed to Dadaists and several of them also incorporated chance into laying out their images. For the Surrealists, collage provided an opportunity to create disjunction, the unexpected combination of images as a means of startling the viewer into a psychological insight. Belgian Surrealist Marcel Mariën (1920-1993) developed a new approach to the collage technique in the 1950s, which are known as étrécissements (shrinkages). The artist took an image and cut away parts of it to produce a new image. The main distinction from collage is the dependence on one or at most two source images. For The Woman of Alost, Mariën cut apart a banknote and a printed image of a nude woman to produce a somewhat cubistic depiction of the subject. The artist had originally trained as a photographer and then worked as an apprentice to René Magritte in the years before World War II. In addition to his étrécissements, the artist created Surrealist photographs and sculptures and worked as journalist and writer. Mariën wrote the first monograph on Magritte in 1943 and in 1979, published a chronological record of materials pertaining to the Surrealist movement in Belgium.

The most prolific technical innovator in Surrealism was Max Ernst (German-American-French, 1891-1976). He created several new ways of applying or manipulating media to create texture and imagery and to incorporate chance effects. In 1925, Ernst pioneered the technique of frottage or rubbing. Similar to taking a rubbing to record the inscription on a gravestone, frottage involves placing paper over a textured surface and rubbing a pencil or other medium across to capture the texture. Ernst used rubbings from multiple textured surfaces to create images which were not related to the original textured surfaces. (See an example at this link Forest and Sun (1931) by Max Ernst.) In 100 Years of Surrealism, part 1, I shared his work The Wood, 1927, in which he used the grattage technique. (Chance Encounters 26) Grattage is essentially the frottage technique applied to painting; a thickly painted canvas is pressed over a textured surface and then scraped to transfer the texture. In many cases, the artist added scraping the paint with combs, squeegees, and similar tools. Ernst’s remaining innovation, decalcomania, involved pressing a sheet of some other material, like glass, paper, or foil, onto a wet paint-covered surface and then peeling it away to create textures in the paint. In his large painting from 1959 The World Is a Story, Ernst created a complex surface of varied textures and colors in which large and small cells containing strange figures float through a dark space above a golden land inhabited by other small creatures. Though it can be hard to tell from a reproduction, in this painting Ernst seems to have used all of his inventive methods and maybe invented a couple more for good measure. Other Surrealists adopted Ernst’s techniques in their works but none used them with the same persistence over a long career.

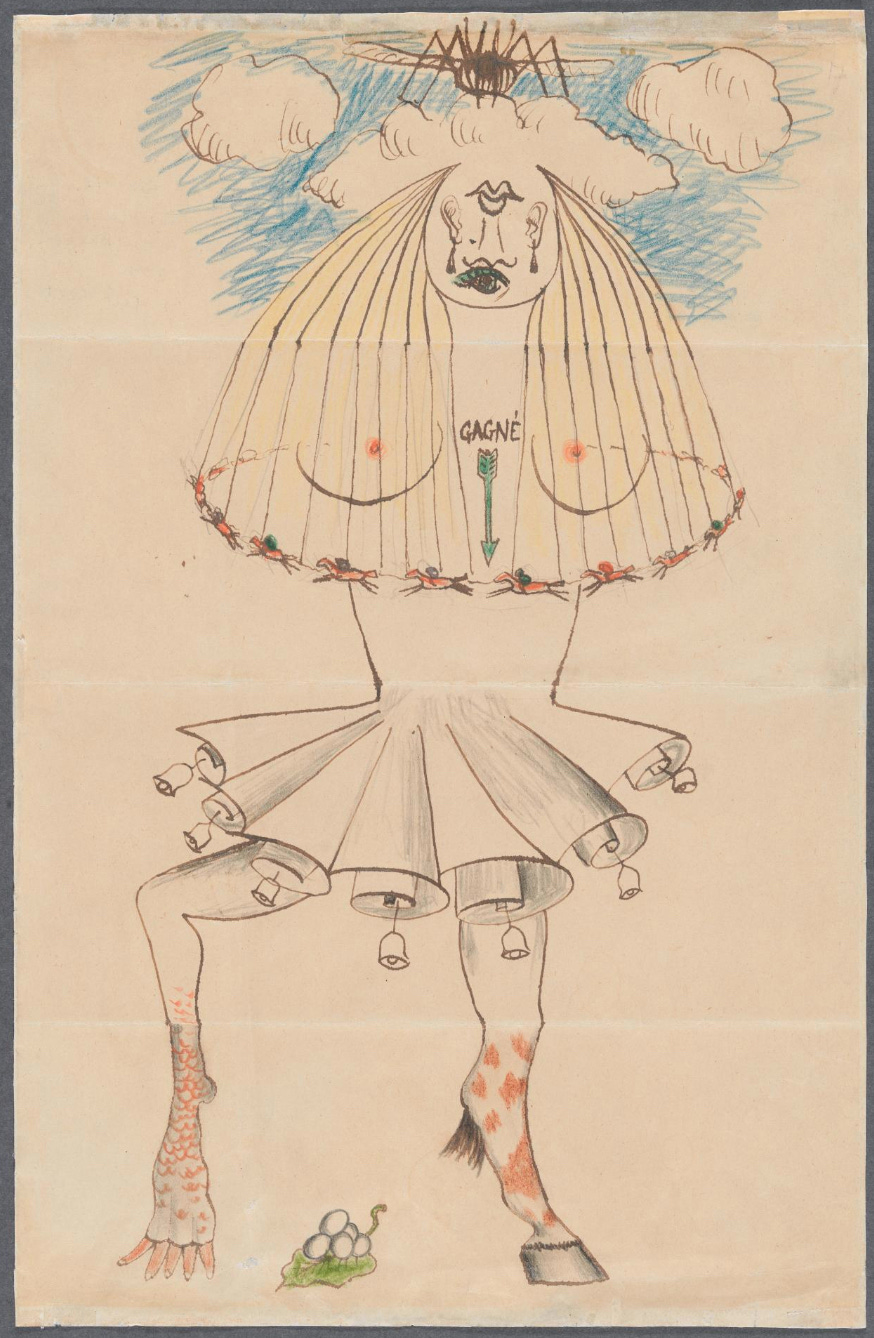

The Surrealists used a variety of cooperative games to create collaborative literary and artistic results. Originally a word game, Exquisite Corpse (Cadavre exquis in French) was one of the most popular Surrealist games and is still used by artists, writers, and musicians today. Each player wrote a word or phrase on a piece of paper without knowing what had been written by those going before. The name of the game comes from one of the first efforts, around 1925, when Surrealist co-founder André Breton and a group of friends produced the sentence “The exquisite corpse shall drink the new wine.” It wasn’t long before the technique was applied to drawing, of which quite a few examples have been preserved, including the one reproduced here. Executed in 1928, this was created by two visual artists, Man Ray and Yves Tanguy, and two writers, Max Morise and Breton. Each participant would draw in turn, leaving a few marks extending past a fold that obscured what had come before. Parts of human figures, animals, machines, clothing, plants, and all sorts of hybrids were incorporated into the drawings produced in Paris during the 1920s and 1930s. In this example, now in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, a young woman’s head, with mixed up facial features, is menaced by a flying spider-like creature in a cloud-filled blue sky. One nice thing about this example is that the folds in the paper are still quite noticeable, so we can see where each artist took over from his predecessor. The first artist, Man Ray, provided the second with the lines and yellow color of the woman’s hair which Morise continued, adding the large breasts. Incongruously the hair leads us to a series of jockeys on race horses circling the figure. A large green arrow labeled “gagné” (won) suggests the finish line of this miniature race while two lines below imply the woman’s torso and cross the central fold. The third artist, Breton, has given the woman a skirt that looks like rolls of paper ornamented with dangling bells. A straight and bent leg protrude from the skirt and cross the last fold. The final artist, Tanguy, made one leg a giraffe’s and the other lizard-like and wrapped up with a leaf holding a clutch of eggs from which a small snake emerges. For the Surrealists, Exquisite Corpse encouraged group harmony, but was also a means of randomized creation which they believed aided in freeing themselves from conventional patterns of thought.

The Surrealists played other visual and word games and experimented with additional means of applying materials in their quest for surrealité. Methods not discussed above include shooting paint at the support (”bulletism”), dripping or spraying a solvent onto dried paint and then blotting it away to alter color and texture (éclaboussure), and blowing wet paint across the surface (soufflage), among others. Just as they experimented with new themes and imagery, if there was a new type of automatism to attempt, someone was sure to try it. Surrealist philosophy encouraged practitioners to seek out these new means of making art and literature as prompts to explore the interior world of their subconscious. The examples of these early 20th century creators has been continued in the century since; artists today use every available material and technology in their creations.

Two essays that I Require Art published last year focused on Surrealist artists who used innovative techniques. Remedios Varo used soufflage, éclaboussure, and decalcomania in her works. (Chance Encounters 14) Wolfgang Paalen invented fumage, a technique of drawing or painting with smoke. (Chance Encounters 18)

Current exhibitions celebrating the centennial of Surrealism:

Histoire de ne pas rire (History of not laughing). Surrealism in Belgium, BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts, Brussels, Belgium. Now open until June 16, 2024. LINK: https://www.bozar.be/en/calendar/histoire-de-ne-pas-rire-surrealism-belgium

IMAGINE! 100 Years of International Surrealism, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium (in cooperation with the Centre Pompidou, Paris), Brussels, Belgium. Now open until July 21, 2024. LINK: https://fine-arts-museum.be/en/exhibitions/imagine

Surrealism and Us: Caribbean and African Diasporic Artists since 1940, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas, USA. March 10 – July 28, 2024. LINK: https://www.themodern.org/exhibition/surrealism-and-us-caribbean-and-african-diasporic-artists-1940

Leonor Fini: Portraits and Passagers, Weinstein Gallery, San Francisco, California, USA. Now open by appointment until June 7, 2024. LINK: https://www.weinstein.com/exhibitions/16-leonor-fini-portraits-and-passagers/

Man Ray: Return To Reason (and other short films), IFC Center, 6th Avenue, New York, New York, USA. Now showing once daily June 2 through 7, 2024. LINK: https://www.ifccenter.com/films/man-ray-return-to-reason/

André Masson: There Is No Finished World, Centre Pompidou-Metz, Metz, France. Now open until September 2, 2024. LINK: https://www.centrepompidou-metz.fr/en/programme/exposition/andre-masson

Upcoming exhibition:

100 Years of International Surrealism, Pompidou Centre, Paris, France. September 4, 2024 – January 13, 2025. Additional details to be announced.

If you know of other museum or gallery exhibitions of Surrealism or of individual Surrealist artists, please let us know in the comments.

This is too weird for me. I liked last week's much better. But, you already knew that