This week’s I’m exploring images of dogs in Modern and Contemporary art, a topic that was inspired by “Dog Days of Summer,” an exhibition of dog-themed art at Timothy Taylor Gallery in New York City through August 23, 2024. While that exhibition focuses on the many different ways in which artists have incorporated dogs into their compositions, I chose to focus on works in which the dog is the focal point. As a dog-loving art historian, this edition was a joy for me to assemble.

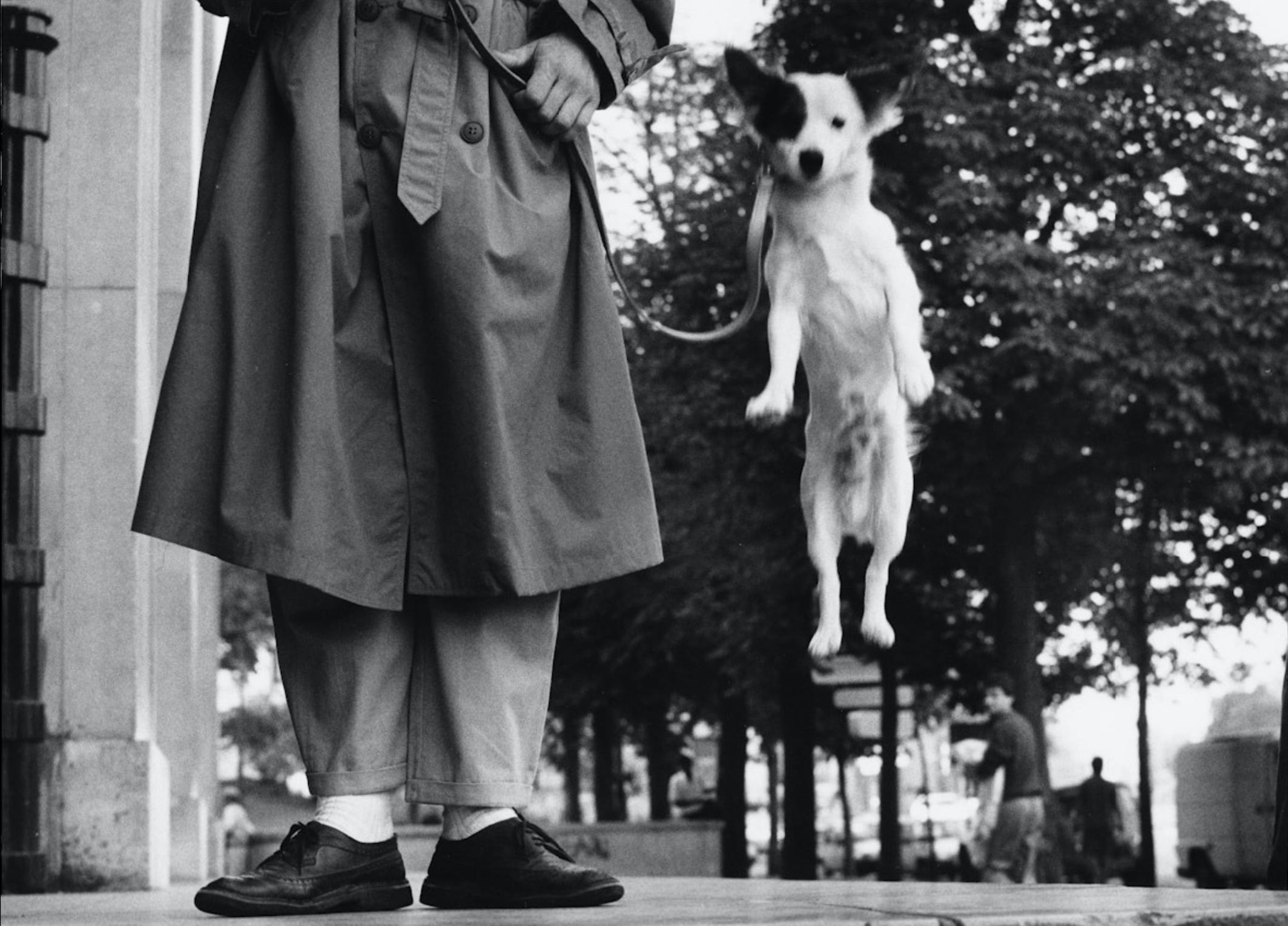

An energetic dog hovers in the air like a leaping dancer. The back paws turn out slightly, echoing the owner’s feet which are anchored to the ground in contrast to the levitating pup. The contrast between the white dog and the dark foliage behind it draws the eye and creates a sense of astonished amusement. Photographer Elliott Erwitt (French-American, 1928-2023) was a master at capturing such moments, especially if they involved dogs.

Dogs are instinctive, they have a memory of the instant, like photography. – Elliott Erwitt

Erwitt was born in Paris to Jewish-Russian immigrants; his family moved to the United States when he was ten years old; later, the artist studied filmmaking and photography in Los Angeles and New York City. After a stint in the Army, Erwitt joined Magnum Pictures, a photographic cooperative where many of the finest 20th century photographers were his colleagues. Working as a photojournalist, Erwitt captured important events like John F. Kennedy’s funeral (1963) and Barack Obama’s inauguration (2009), and memorable images like Vice-President Richard Nixon poking the lapel of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev during the Cold War (1959). Many of Erwitt’s most captivating images, though, are the moments of everyday life the artist caught as he traveled the world. Dogs were a favorite subject and the artist eventually published five books of his dog photos. Every type of dog personality appears in Erwitt’s photographs.

Another lively-looking black and white dog is featured in Tama, the Japanese Dog by Édouard Manet (French, 1832-1883). A leading Realist painter in mid-19th century Paris, Manet recorded the likeness of the little dog in the dark tones characteristic of his Realist style. (See Chance Encounters 5 for more about the artist.) The dog, a Japanese Chin brought to France in the early 1870s by Henri Cernuschi (Italian-French, 1821-1896), looks alertly to the left. The long brushstrokes of the background contrast with the short textured strokes that capture the dog’s tufty coat. The dog’s tail is painted with long, curving strokes in imitation of its more feathery texture. A doll lies between the viewer and the dog, its diagonal position acting as a pointer toward the focal point. The red and black robed doll looks Japanese, or perhaps Chinese, and is a second reference to the dog’s exotic origin. Cernuschi was a banker and collector of Asian art who left Paris for East Asia around 1870, returning with an art collection which he expanded and then donated to the French state on his death. Manet, like other artists of the time, was fascinated by Japanese art, so it’s not surprising that he would be part of Cernuschi’s circle. Manet was not the only artist in that circle; the dog is also the subject of a painting by the Impressionist Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919), now in the collection of the Clark Art Institute.

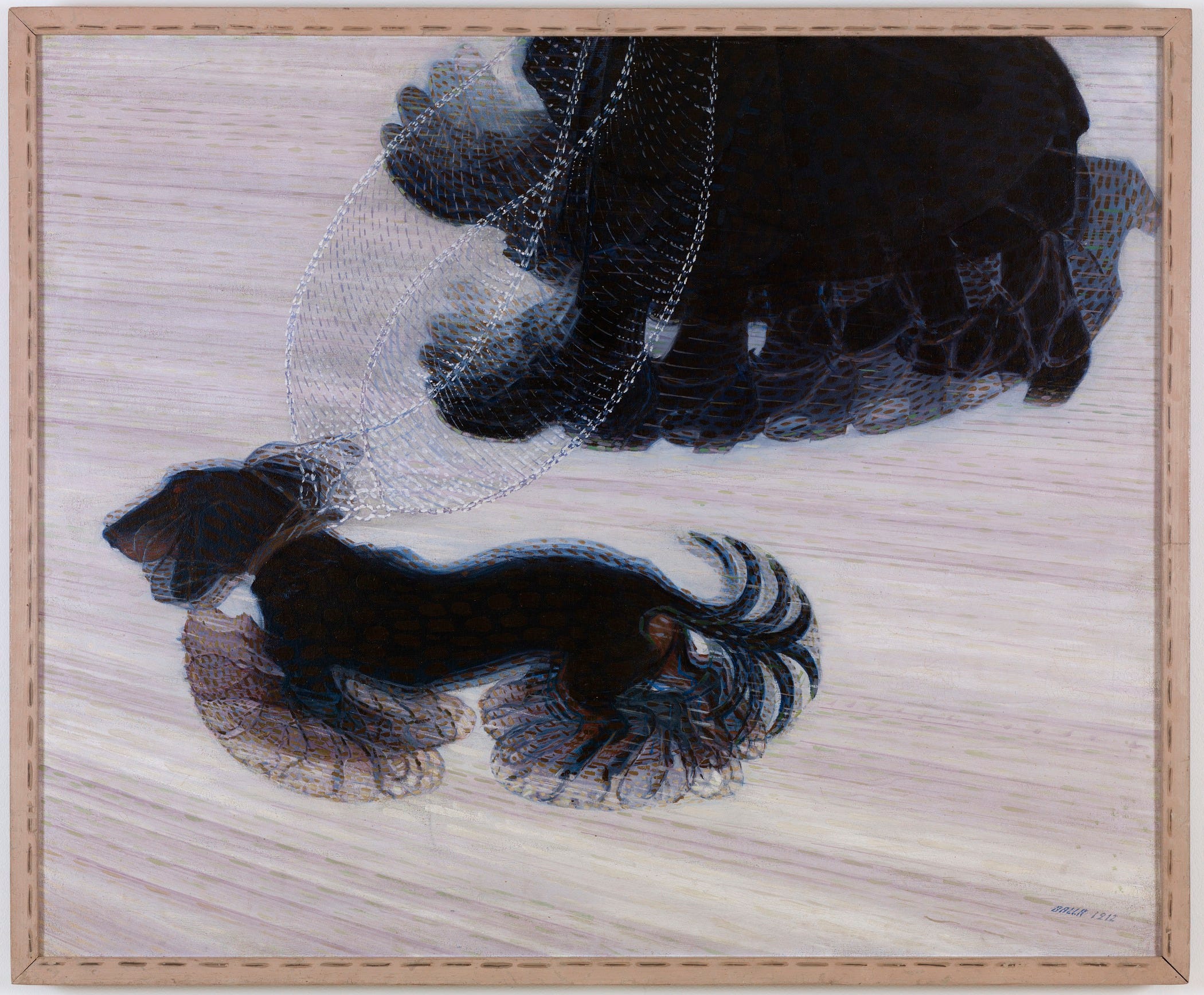

This well-known painting is an iconic example of the Futurist movement, of which the artist, Giacomo Balla (Italian, 1871-1958), was a founding member. Futurism was one of the early 20th century European artistic movements that developed in response to Cubism. (See Chance Encounters 11 for more about Cubism). Italian art of the early 20th century was not progressive, in part because the glorious history of Italian Renaissance and Baroque art pressured artists to maintain those traditions. In Milan in 1909, the Futurists announced their rejection of the past and their determination to celebrate technology and energy. Unfortunately, the Futurists were also avid nationalists, supporting the regime of Benito Mussolini and the alliance with Nazi Germany.

An important influence on Balla’s style was divisionism, a variant of Neo-Impressionist pointillism, which led him to use small but visible brushstrokes in this work. These create a halo of visual energy around the objects in this painting. The other influence, Cubism, encouraged the Futurists to break forms apart and then repeat them to convey movement and energy. For many Futurists, subject matter was drawn from machinery, violence, and war, but Balla tended to choose whimsical, every day themes as he did here. The title Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash describes the scene but also uses a term key to Futurism – dynamism, which the Futurists defined as the energy inherent in all objects. Here, Balla captured the movement of the Dachshund and the feet of the woman walking it but also the energy inherent in their surroundings. The striated ground and the repetition of objects combine with the divisionist brushwork to bind the image into an energetic whole. The energies of objects differ from one another, though. The Dachshund’s tiny legs are repeated so often that they disappear into a blur while the larger feet of the woman remain distinguishable.

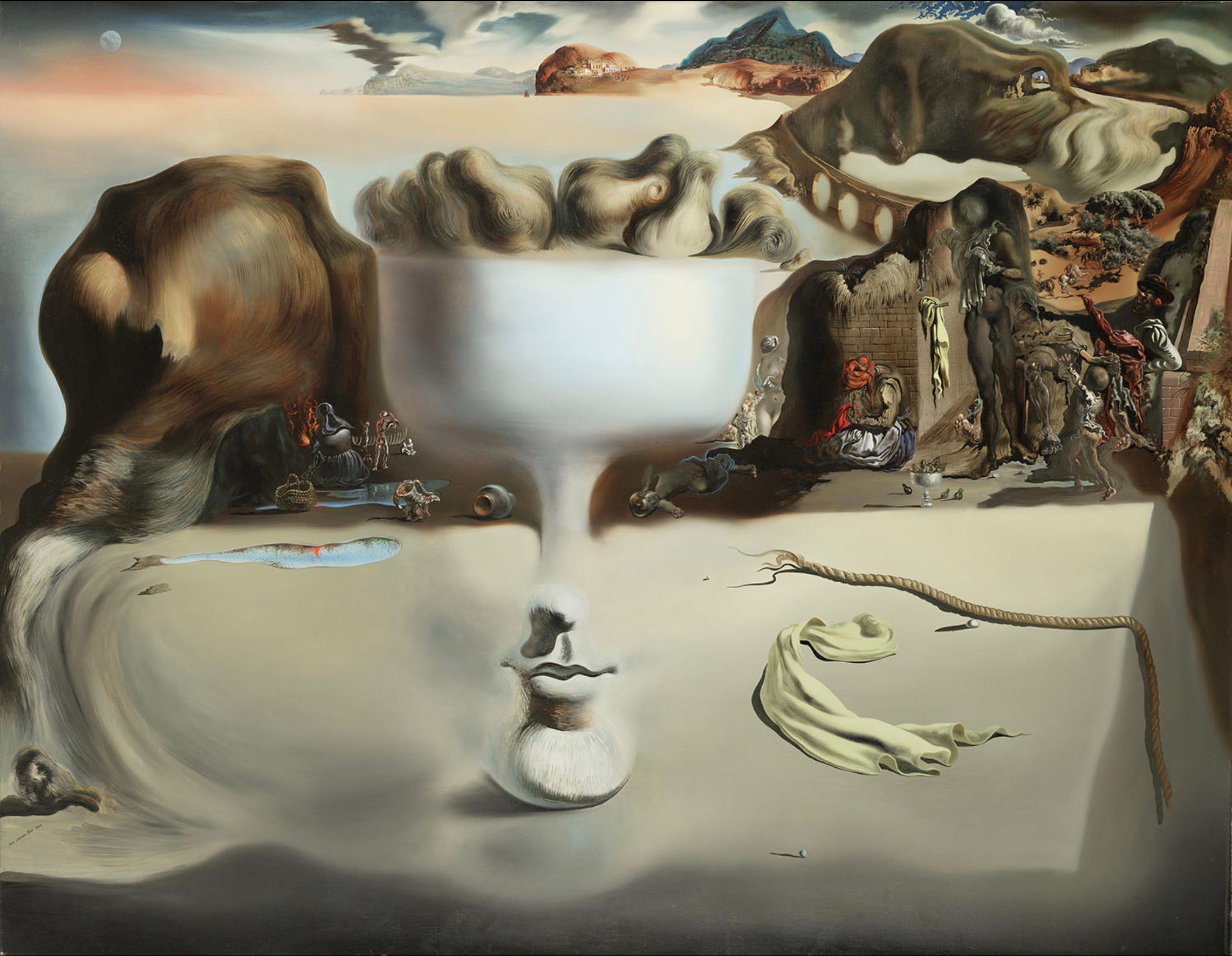

Did you look at the image above and wonder where the dog was hiding? Apparition of Face and Fruit Dish on a Beach is an example of the metamorphic illusionism that often characterized Salvador Dalí’s paintings. Like many Surrealists, Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989) was interested in dream imagery. (See Chance Encounters 26 and 33 for more on Surrealism.) One of the tools that the artist used was combining incongruous images that morph into one another as we observe them. Even without the title, the smiling mouth in the center of the composition allows us to recognize the face floating within the pale expanse of a beach. But is it a beach? The line of shadow to the right creates the impression of a table’s edge, covered by a cloth. If it’s a table, what is the object that we interpreted as a face? The broad white forehead suddenly looks more like a stemmed dish, filled with pears. At least, they look like pears from a distance; upon closer observation, they appear strangely hairy, and suddenly we are looking again at a face topped by a mass of curly hair. Beyond the pears/hair, we see rocky hills, a body of water, and a cloudy sky with a full moon. But why is this painting in an essay about dogs in art? Here we must draw further back and take in the whole painting to notice that the rounded brown hill to the right of the forehead/fruit dish is the back hip of a long-legged hound. Its head is found near the upper right corner, comprised of the second hill from the right edge and some flowing white water. A row of arches in a bridge also make the dog’s collar. These are just the main features of this this complex composition. All along the line of hills are figures and objects of varying scales, interacting in small narratives. For Dalí, the painting reflected his love of and fear for Spain during the ongoing Civil War, but the viewer is left to decipher the many images and stories according to their own interests, dreams, and fears.

In a completely different vein, Alex Katz (American, b. 1927) has created a work that seems completely obvious in its execution and meaning. Katz denies any interest in creating a narrative, but it’s difficult to avoid imagining that Sunny has been romping through the high grass at the lake’s edge before sitting, panting in front of the artist.

I’m always searching for a balance between abstraction and representation. – Alex Katz

Sunny 4 is part of a series of works by Katz depicting his Skye Terrier and is by far the largest painting in this group. Whatever their individual styles or subjects, Pop artists create works that are emotionally detached as a way of rejecting the highly individualized, psychologically revealing art of the previous generation of Abstract Expressionists. Katz’s Pop Art approach involves using mostly flat, unmodulated color and simplifying form. Working on a large scale led the artist to imitate billboard design in which large areas of bold color define the composition. In this painting, that’s noticeable in the oblong pink tongue that stands out amid the long gray and white strokes of the dog’s hair and the slightly exaggerated diagonals of the ears which stress the geometry underlying Katz’s composition.

Painted just a few years after Katz’s Sunny 4, Andrew Wyeth’s Ides of March demonstrates the artist’s mastery of realism and subtle color palettes. Wyeth (American, 1917-2009) painted in a realist style, working against the grain of the avant garde in American art during his lifetime. One consequence of that was a mixed reception, with his works attracting a large popular following and extensive sales while art critics and others in the avant garde community were dismissive. In 1977, art historian Robert Rosenblum described Wyeth as both the most overrated and the most underrated artist of the 20th century. Wyeth worked in either watercolor or tempera paint. Tempera, in which pigment is mixed into egg yolk, was the most common medium for panel paintings before the invention of oil paint in the late 14th or early 15th century. Because it is quick-drying and difficult to master, the more versatile, slow-drying oil paint quickly replaced it as artists’ preferred medium. Wyeth’s mastery of tempera is unusual among 20th century artists and it allowed him to create the subtle tonal variations for which he is best known.

It’s all in how you arrange the thing…the careful balance of the design is the motion. – Andrew Wyeth

Ides of March is an example of Wyeth’s tonal subtleties, with the sunlit yellow Labrador Retriever acting as the bright focal point in front of the blackened fireplace. The artist ties the composition together by reusing the golden tones of the dog’s fur in the stone wall at the left side. The dog seems restful, but a closer look shows that is isn’t sleeping but watching. Behind the dog, a column of smoke rises toward the chimney from the dying fire and the light catches on the spiky metal forms hanging to the left. Suddenly, the quiet scene reveals a darker side, reminding us of the threat inherent in the title. “The Ides of March” was the moment Julius Caesar was warned of in Shakespeare’s play. It is this kind of duality of meaning that makes Wyeth’s best paintings truly compelling.

No contemporary artist is more associated with dogs than photographer William Wegman (American, b. 1943). His still images and short films of Weimaraners in costumes, surprising or elegant poses, or with unusual props are familiar to many, including those who grew up watching Sesame Street. Wegman set out to be a painter, studying painting in the late 1960s and achieving inclusion in museum and gallery shows internationally in the 1970s. Also in the 70s, the artist acquired Man Ray, his first Weimaraner and canine collaborator. After Man Ray died in 1982, the artist waited four years before acquiring Fay Ray, who was the first dog to star in his Sesame Street videos. Since then, four generations of Fay Ray’s descendants have been featured in Wegman’s works. In View Points, a Weimaraner sits gazing ahead toward a curving sheet of reflective red plastic. The dog’s reflection seems to convey a different mood, almost as if it is a different dog all together. Wegman works in both black and white and color photography. In black and white, the emphasis is usually on the subtle textures of the dogs’ coats, while color images like this one celebrate the interaction of the dogs’ gray-brown coats with the colors around them. The subtle tones of the dog’s coat remain apparent in the reflected dog and the bright red color reflects on the dog’s chest and facial features. As entertaining as I find the costumed dogs in Wegman’s videos and photos, images like this one better convey the artist’s empathy with and understanding of his canine collaborators.

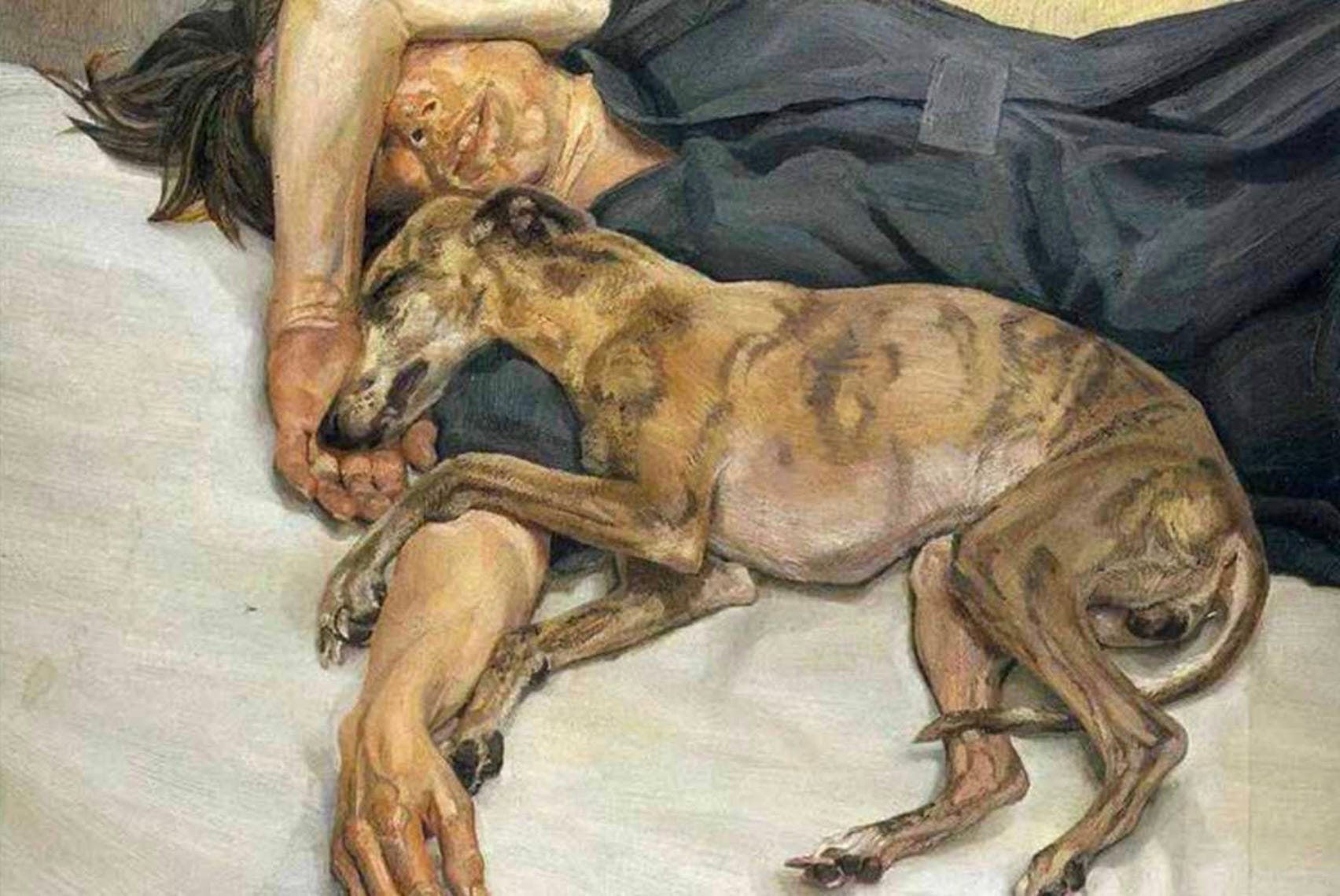

Another contemporary artist with a deep love for his dogs was Lucian Freud (British, 1922-2011). Though the artist’s dogs, mostly Whippets, don’t dominate his works in the way that Wegman’s do, the dogs appear in several paintings, of which my favorite is Double Portrait. Freud was born in Berlin and was the grandson of the trailblazing psychiatrist Sigmund Freud. The artist’s family moved to England to escape the rise of Nazism and Freud became a British citizen in 1939. Considered one of the most important portraitists of the 20th century, the majority of the artist’s subjects were family members and friends. Freud is known for his careful attention to flesh tones painted in thick paint (impasto). This can make some of his portraits uncomfortable and even disturbing to look at; his portrait of Queen Elizabeth II (2001) was the subject of extensive criticism, such as The Sun’s headline “It’s a Travesty, Your Majesty.” In this painting, human flesh isn’t the artist’s focus, instead it’s the brindle coat of the sleeping dog. The pose, a sleeping dog curled against the body of its human, is familiar to dog owners. The intertwining of the dog’s front paws with the arm and the person’s reddened palm cradling the dog’s muzzle strike me as a reflection of Freud’s love for his dogs.

The subject matter is autobiographical, it's all to do with hope and memory and sensuality and involvement, really. – Lucian Freud

I close with one of the works in the “Dog Days of Summer” exhibition at Timothy Taylor Gallery, Hungry Borzoi by Justin Liam O’Brien (American, b. 1991). Any dog owner will recognize the attentive hopefulness on the white dog’s face, though the small plate holding a single cherry would seriously disappoint any hungry dog. The green tablecloth creates a vivid frame for the dog’s head and a strong contrast with the dog’s white fur. The curves of the blue plate stand out against the rectilinear edges of the green-covered table; the plate balances the composition by adding visual interest to what would have been an empty corner. The red cherry calls attention to itself by its isolation and by the contrast of its small red spot with the large expanse of green. The triangular folds below the dog echo its pose and emphasize the overall elegant simplicity of the composition. Such elegance is well suited to the Borzoi breed, a long-legged, long-bodied dog with, as is obvious from this painting, a slender pointed head. The curling white hair is also characteristic of the breed, and the intrusion of delicate white lines into the green reinforces the artist’s emphasis on graceful stylization. This work’s subject is not typical of the artist’s body of work, which focuses on narrative scenes of young men in a variety of social and emotional situations. The smooth contours, bright colors, and slight, subtle shading are consistent with the artist’s style, though, and the work also follows O’Brien’s practice of building compositions of interlocking, clearly delineated shapes.

Dogs have served as artists’ subjects since ancient times and because they come in such a wide variety of sizes and shapes, dogs have not only depicted their own existence, they’ve also stood in for every aspect of human life. This small collection of Modern and Contemporary images conveys only a taste of the possibilities of the dog as a theme. Most of these artists chose to represent canine companions many times, because after all, dogs are humans’ best friends.

“Dog Days of Summer,” Timothy Taylor Gallery, 74 Leonard St., New York, through August 23, 2024. https://www.timothytaylor.com/exhibitions/237-dog-days-of-summer/

Wow, what an amazing selection of dogs in art—and I write as someone who is primarily a cat person (though we had loveable dogs as pets when I was a child). Every one of these paintings is a treasure, though I’ll flag the Balla as fascinating for the way it shows motion and contrasts the dog with the human. So clever, and so well done! Here’s a fun one I ran across yesterday to add to your collection: https://www.mutualart.com/Artist/David-Hockney/80BD8AA4259A2BFC A study in contrasts in its own silly way!

Unread discussions are bold but hard to distinguish—try increasing your browser's zoom or adjusting your display's contrast settings for better visibility. Alternatively, use a black screen to rest your eyes between reading sessions.https://blackscreen.onl