This edition of Chance Encounters concludes our series honoring the 100th anniversary of Surrealism. In case you missed them, the other editions in the series are 100 Years of Surrealism, part 1, The Methods Behind the Madness, and Surrealist Women. In truth, Surrealism has inspired so much art in the last hundred years that a project like this only skims the surface of the subject. In this edition, my focus is on the continuing relevance of Surrealist philosophies, methods, and visual effects in contemporary culture.

Strictly speaking, Surrealism is an artistic movement that originated in the 1920s; participants believed in the transformative possibilities of freeing the subconscious mind from conventional restraint. This year’s anniversary celebration marks the 1924 publication of the Surrealist Manifesto by André Breton. The publication and its author served as a focal point for the growing movement. After Breton’s death in 1966, the Paris Surrealist Group attempted to carry on but in 1969, member Jean Schuster announced the formal disbanding of the group in the newspaper Le Monde. The implication was that if Breton’s original group was closing up shop, Surrealism was over. His announcement prompted consternation and many letters from international Surrealist communities announcing the continuing vitality of the movement. From that time to this, there have been many artists maintaining Surrealist practices, and often expressly claiming their places in the Surrealist movement.

The painting above, created by painter Inka Essenhigh (American, b. 1969), looks a bit like a scene from an animated film. The dark tree and background enclose a bright procession of vaguely human figures watched by similarly suggestive forms. Such fantastic images are common in the artist’s work. Essenhigh often begins by using the Surrealist practice of automatic drawing – allowing her hand to move freely across the surface without conscious control. In Surrealist theory, this activity allows the subconscious mind to participate in the act of creation and it was a favored method of early Surrealists Joan Miró and André Masson. The curving shapes and swirling lines throughout Fairy Procession hint at their origins in automatic drawing. Essenhigh has said that she is exploring the “deeply mysterious nature of the world” in her paintings, but also that Surrealism seems to be inherent to her artistic approach.

I can’t help it! Even if I make a picture with nothing distorted it is read as surrealistic. It just oozes out of me. – Inka Essenhigh

Some years ago, I was skimming a group of exhibition reviews when it occurred to me that nearly all of the dozen or so that I’d looked at had connections to Surrealism. From that day, I started noticing Surrealism everywhere I looked. Surrealist imagery and effects can be found in animated and live-action films and television, in music videos, and especially in advertising. Having grown up with talking rabbits and mice, superheroes of every imaginable type, and witches, ghosts, and vampires throughout the media environment, the strangeness of all of this barely registers with most contemporary viewers.

Startling disjunctions and depictions of dream-like realities are often simply conventions, habitual forms used because they have been employed in moving pictures since Salvador Dalí began collaborating with film-makers in the 1920s. (Examples of Dalí’s Hollywood collaborations can be found here and here.) In today’s environment of omnipresent imagery, the odd elements in advertisements are designed to stop the consumer from changing channels or scrolling past. This ad for Drambuie liqueur (2012) uses imagery inspired by Dalí and others to create an eerie black and white reality in which only the product provides color.

Chino Moya (dir.) A taste of the extraordinary, 2012. Commercial for Drambuie liqueur, by Sell! Sell! Agency.

In addition to its influence in popular culture, Surrealism is a dominant mode of expression in the fine arts. Having decided on this topic to close the series, I began collecting artists to consider; soon I had over a hundred and had barely begun my research. In the end, I decided to limit myself to 21st century artists, thinking that with only a quarter century to consider I could solve my dilemma. I was soon swamped again. Choosing just eight of those many works for this edition was a real challenge. What has made Surrealism so appealing to so many artists and for so long?

It’s the transformative nature of Surrealism that continues to make it relevant. Surrealism is inherently political. It started as a protest movement and a way to counter fascism and authoritarianism, so that’s why it still can be a very powerful political weapon for today. It will always be relevant. I would say, it’s a future movement. – Patricia Allmer, University of Edinburgh

For many artists, as for art historian Allmer, the ability of Surrealism to challenge political and social restrictions is its most relevant and powerful quality. Among women artists, Surrealism provided, and continues to provide, a framework within which to critique societal limitations as discussed Part 3 of this series.

Julie Curtiss (French, b. 1982) asserts, as I have, that traces of Surrealism are “ever-present in the arts and in life.” No Place Like Home (2017) is one of a series of works in which rolled and curled chestnut hair carries the meaning of the images. Here it covers or replaces a roasted bird in an eerie echo of Meret Oppenheim’s iconic 1936 Object (Le Dejeuner en fourrure) (Object, Luncheon in Fur). The woman who carries the platter is cut off by the right edge of the composition, reducing her to pairs of hands and breasts. The hair-roast appears as a sort of sacrificial offering, reminding us of how women’s individuality can disappear into their labors as cooks, mothers, and wives.

The exploration of internal and external realities through art has its roots in the early Surrealists’ embrace of Freudian theories. Leyla Cui, a young Chinese artist, illustrator, and writer, conveys the psychological challenges of womanhood in her mixed media works. In The Unveiled Gaze (2023), the layered structure of the work echoes the layered narrative. The slender young woman, seen from the back, appears threatened by both external (the thorny walls and the winding thread) and internal forces (the flames of the keyhole), yet she seems oblivious to the golden key which might unlock her inner self and which hangs just above her head.

The distortions and startling elements found in Surrealist art often provoke laughter. This aspect appears frequently in surreal popular culture, but it can also be a tool for the fine artist who wishes to challenge tradition. Sculptor Tony Matelli (American, b. 1971) is adept at creating works which startle and confuse. He is probably best known for his series of life-like painted bronze plants which appear to sprout from gallery walls and floors. Bread Head (2018) is one of the artist’s series of apparently Classical sculptures combined with food. In this case, a cast stone head that looks like a decayed fragment of a Greek or Roman work is combined with life-like slices of bread and hotdog, which are in fact made of painted bronze. The work is absurd and humorous, but it also challenges us to consider what we value and why.

I’ve always thought that for an artwork to be successful, it needs the viewer to become invested in it. Ideas need to have seductive power in order to be absorbed and considered. This is the ultimate lesson of religious art, and even Hollywood—the viewer needs to be seduced. – Tony Matelli

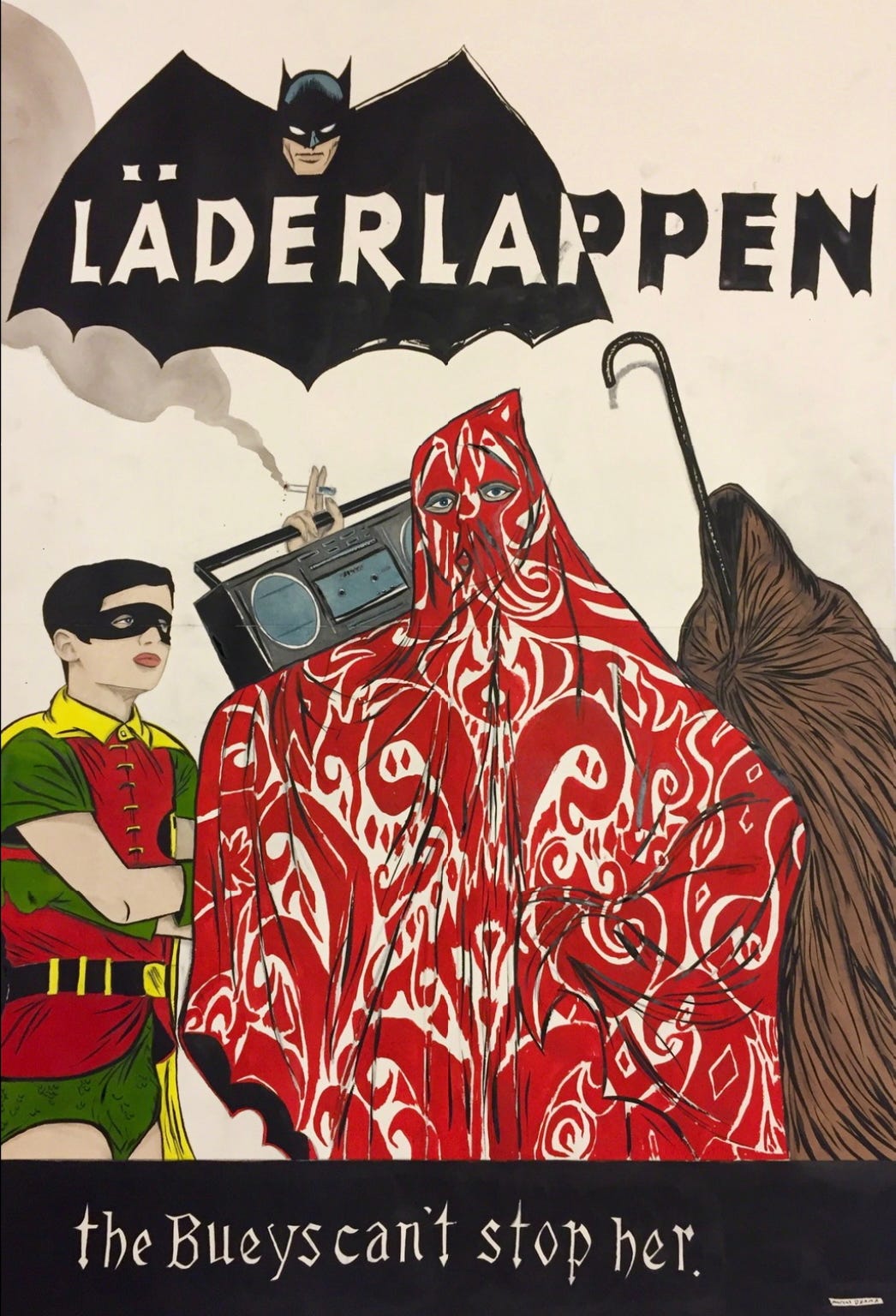

In a humorous mash-up of Pop Art and Surrealism, Marcel Dzama (Canadian, b. 1974) incorporates a punning reference to the 20th century Performance artist and art theorist, Joseph Beuys (pronounced “boyss”). Though Beuy’s name is misspelled, the blanket-wrapped figure in the right background mimics his appearance in famous photographs of the 1974 performance I Like America and America Likes Me (Coyote). In The Bueys can’t Stop Her (2017), the layout is reminiscent of a comic book cover, including the logo-like Batman (“Läderlappen” in Swedish) at the top. Combining popular culture figures like Batman and Robin with an art historical figure (Beuys) who would be unfamiliar to most fans of the superheroes creates the kind of disjunction that Surrealists utilized to provoke viewers to rethink their expectations while the punning title connects to Belgian Surrealist René Magritte’s fascination with language and word games.

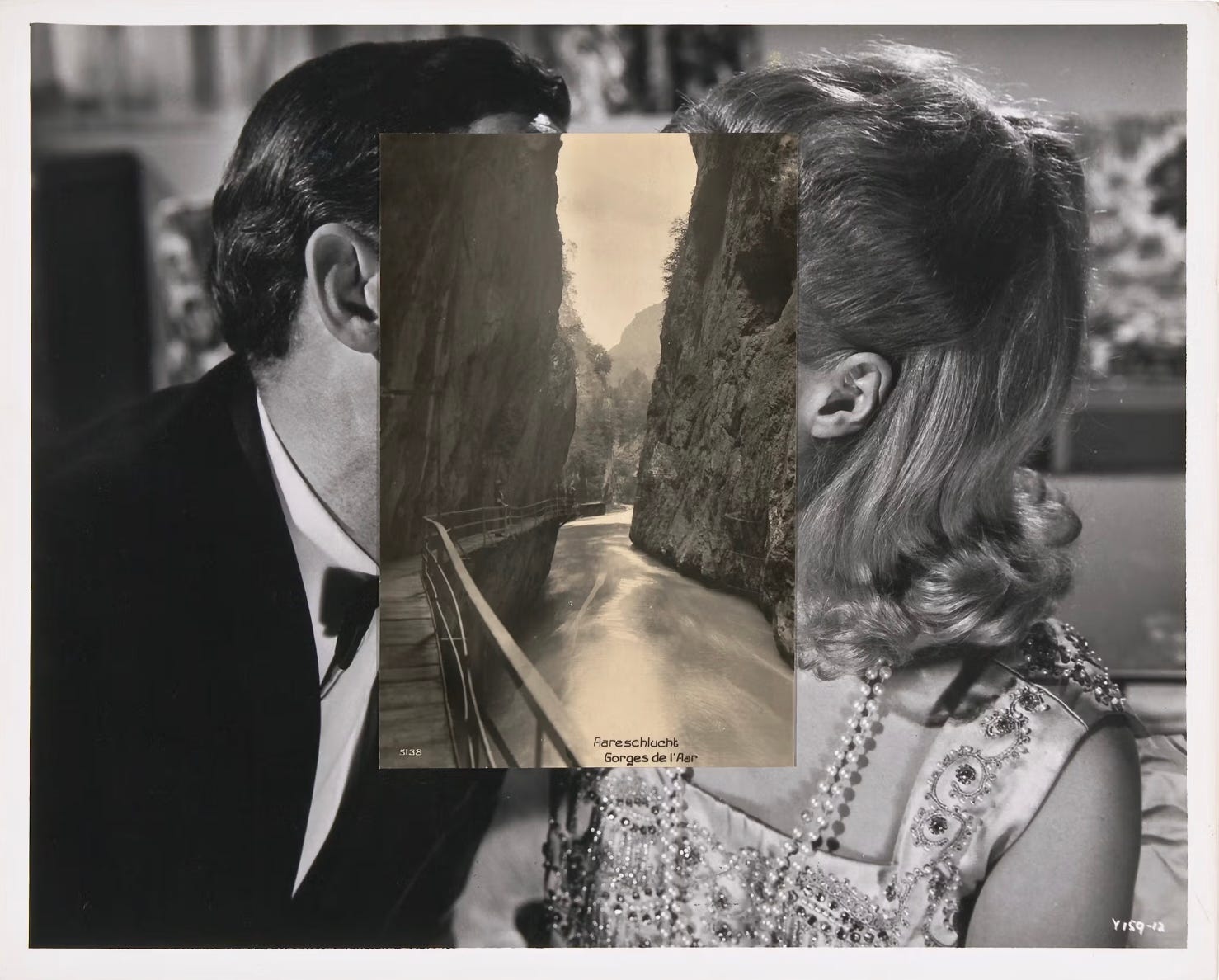

Another artist who creates disconcerting combinations is John Stezaker (British, b. 1949) who makes collages from found images. Pair IV (2007) is typical, a film or television still onto which another image has been superimposed. In this work, a couple is overlaid with a sepia-tinted picture postcard of the Aare Gorge, a popular tourist attraction in Switzerland. Stezaker has placed the postcard so that the walls of the gorge roughly approximate the profiles of the people in the photograph. The humorous juxtaposition hints at other comparisons one might make between the two images – indoors vs. out, artificial vs. natural, and the gulf that exists between people no matter how physically close they might be.

The vividly colored still life and landscape paintings of Nicolas Party (Swiss, b. 1980) are produced with chalk pastels on canvas. The artist was first drawn to these colors while creating spray-paint graffiti in his teen years. In his still life paintings, the fruits and vegetables are recognizable yet biomorphic – as if they are evolving from inanimate food into amoebic creatures. This is most noticeable in the orange pear-shaped object which seems to be cuddling up to the bright purple fruit which bends its neck toward the pink apple and the white pear. The way that the thread-like stems protrude from depressions in the objects enhances this biomorphic effect. Biomorphic forms are found throughout the works of early Surrealists like Joan Miró. Though Miró’s works are more abstract than Party’s, both artists create a fantastic world that stretches the viewer’s imagination beyond their mundane experiences.

I close with a very large, extremely abstract untitled painting by Hélène Delprat (French, b. 1957), which is included in the exhibition “Surreal Legacies” (see below). Delprat’s career has followed an unusual path. Though the artist worked as a painter from 1985 to 1995, she veered away from painting into video, theater, and installation during the late 1990s and into the 2000s. Upon returning to painting in the late 2000s, Delprat began to draw on her varied interests and her reading of ancient, Medieval, and modern texts.

Intellectually, I start from everything I see ... there is no prep work, except all of this food, all this reading, all these curiosities, all the photos that I take. – Hélène Delprat

In this painting the artist has created a world of color and pattern in which a cartoonish black figure rushes toward a white door-like opening from which a silhouetted figure peers out. The layered realities and the complex patterning that flows and eddies across the painting prevent us from anchoring the meaning to a single context. This denial of a single narrative harks back to Surrealism’s repeated challenges to artistic and cultural traditions and reminds us that understanding may require accepting ambiguity.

This has been just a glimpse at the broad and deep stream of Surrealism in Contemporary art and culture. Though the movement began as a response to the specific context of post-World War One France, the philosophies proposed by André Breton and later Surrealist thinkers turned out to be applicable to a wide variety of cultural contexts throughout the 20th century and into the present. Surrealism has become a way of thinking, of looking at the world, and of expressing those thoughts and visions, justifying the founding theorist’s expressed belief:

I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality … – André Breton

This is our last post for 2024. Look for our first post of 2025 on January 11. Thank you for reading, subscribing to, and sharing our work. Best wishes for the New Year.

The anniversary of Surrealism’s founding document inspired numerous exhibitions throughout the past year, and many will continue or open in the New Year. I’ve listed those I know of below. If you learn of others, I hope you’ll share them in the comments. Please remember to check for closures during the holiday season.

• “Surrealism,” Centre Pompidou, Place Georges-Pompidou, Paris, France, through January 14, 2025. Other venues in Paris are presenting programs about Surrealism through January 18, 2025. Find more information here.

• “Surreal Legacies,” Hauser & Wirth, One Monte-Carlo Place du Casino, Monaco, through February 8, 2025.

• “But Living Here? No Thanks. Surrealism + Antifascism,” Lenbachhaus, Luisenstrasse 33, Munich, Germany, through March 2, 2025.

• “The Traumatic Surreal,” Henry Moore Foundation, 74 The Headrow, Leeds, West, Yorkshire, UK, through March 16, 2025.

• “Forbidden Territories: 100 Years of Surreal Landscapes,” The Hepworth Wakefield, Gallery Walk, Wakefield, West Yorkshire, UK, through April 21, 2025.

• “Fotogaga: Max Ernst and Photography,” Museum für Fotografie, Jebensstrasse 2, Berlin, Germany, through April 27, 2025.

• “The Key to Dreams. Surrealist Masterpieces from the Hersaint Collection,” Fondation Beyeler, Baselstrasse 101, Riehen/Basel, Switzerland, through May 4, 2025.

• “The Subterranean Sky. Surrealism in the Moderna Museet Collection,” Moderna Museet, Exercisplan 4, Skeppsholmen, Stockholm, Sweden, through January 1, 2026.

Opening next year:

• “100 Years of Surrealism,” Fundación Mapfre, Sala Recoletos, Paseo de Recoletos, Madrid, Spain, February 4 to May 11, 2025.

• “Rendezvous of Dreams. Surrealism and German Romanticism,” Hamburger Kunsthalle, Glockengeisserwall 5, Hamburg, Germany, June 13 to October 12, 2025.

• “100 Years of Surrealism,” Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, November 2025 to April 2026.